Forged by Ven. Father Felix Rougier, M.SP.S., during the crucible of the Mexican Revolution, the spiritual approach, Loving Attention, proved effective in forming priests “united in Christ and guided by the Holy Spirit.”

Oftentimes, during the most difficult periods of history, the Lord is most generous with us. He inspires novel integrations in the spiritual life that can facilitate our closeness to him and our ability to love others with that same generosity. Because, as Vatican II’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et spes) suggests, part of the “responsibility members of the Church carry is to read the signs of the times and interpret them in the light of the Gospel.” We need a new awareness of how to live our faith this way, confronting the needs of our age. 1 Loving attention is a new integration of traditional spiritual practice and prayer, that is especially apropos for the Church, and particularly a “pearl of great price” for busy, overworked priests of today. We live in times rocked with the sex abuse crisis and the ordained priesthood, with dire predictions of grossly inadequate numbers of active priests to serve a growing Catholic population, and with the reality of closing or clustering parishes. While accessible to everyone, the practice of Loving Attention is an especially empowering attitude of “prayerful living” that can help re-energize and equip priests with tools to delve into the challenge of ministry in this context.

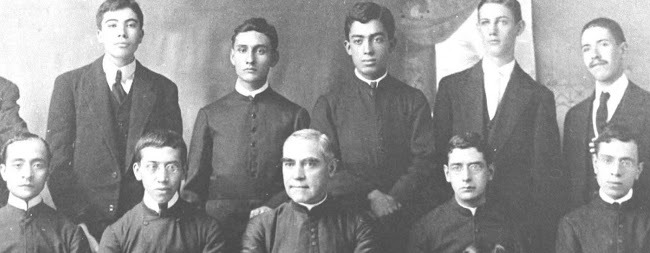

In fact, the practice of Loving Attention was forged in the crucible of very difficult times during the Mexican Revolution, and proved very effective in forming priests who were “united in Christ and guided by the Holy Spirit to press onward towards the Kingdom.” 2 They celebrated Mass in homes, dodged authorities and were often martyred. Loving Attention was the innovation of Ven. Father Felix Rougier, M.SP.S., (1859-1938), the co-founder of The Missionaries of the Holy Spirit. This religious congregation of priests was founded in 1914 in Mexico, at the height of ecclesial oppression by the Mexican government. The charism of the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit is spiritual guidance of souls (especially of priests), spiritual direction, and the Sacrament of Penance. When Pope Pius X heard of the main aim of this congregation, he exclaimed, “Blessed be God! This is what the Church needs most at this moment; to have good spiritual guides.” 3 We can say the same for our age!

What does Venerable Fr. Felix Rougier, M.SP.S., mean by the term: Loving Attention to God? Fr. Felix coined the term, meaning a practice of “walking in the presence of God, to referring everything to God that you encounter, to doing everything for God, and in all circumstances, to see the hands of God.” 4 He suggested that all that was necessary to live this way was to direct the glance, or focus of your heart, regularly towards the Lord, and the people whom you encounter. In this, he synthesized a vision that pulled his entire life into the love of God: the crosses, the mission with the new Congregation, and the joys of life all, becoming a unified whole in the hand of a loving God.

He guided his priests to “live this life of prayer,” 5 by encouraging them to “impregnate their whole life with God as this powerfully helps to make all acts—small and large—of God, for God and according to God.” 6 To do this, he asked them to follow through with their daily commitment to structured times of prayer, and Eucharistic adoration, as well as to develop a spirit or attitude of prayer that pervaded their entire lives. For Fr. Felix, this pervasive attitude of prayer, or Loving Attention to God, was a way to organize, or integrate, his entire life and service in persuing God, making his life an expiation, drawing graces to others.

By naturally directing the attention of your heart towards God in prayer throughout the day, as Ven. Rougier suggested, one was able to become gradually transformed into Christ. One was able to join with the Lord’s own affections and intentions for others. The natural human inclinations of the heart, and the perceptions of the mind, were expanded and irradiated with the Lord’s own light and indomitable love. This simple human glance inward and towards God for the needs of others, was a means, then, both of one’s own sanctification, as well as a way to pray for and obtain graces for others. One night with a group of religious brothers, sisters and priests, Father Felix illustrated the impact of this simple practice by sharing a story that exemplified his own transformation in the light of Christ. He was an army chaplain in Columbia. One night during an armed conflict, he walked onto the battlefield himself. He told them that he helped the wounded on both sides, saying, “How much I saw in those suffering people, the face of the suffering Christ, especially in the wounded enemy.” 7 Through this simple practice of Loving Attention, of drawing his gaze towards Christ in the midst of everything, Fr. Felix shows us how to take on “the joy, hope, grief and anguish of the people of our time…as followers of Christ.” 8

Today, in this media age, many people, including priests, succumb to “new forms of slavery in living and thinking,” 9 with internet pornography, an addictive pace of life, and an unrelenting pursuit of both prestige and materialistic gain. The insights of Father Felix can help us all reverence and direct our mental focus, and our intention of heart, so we are able to be transformed into other Christs, and “carry on his work under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.” 10

Moreover, the practice of Loving Attention helps us grow in spiritual sensitivity, and freedom of heart, so we are more able to respond to the movements of grace from within, offering our lives as an expiation, pulling down graces for others. By learning to live in the mutual gaze between Jesus and ourselves, we enter into a very personal, grace-filled dynamic, stepping into a living channel of grace that moves and orients all of our actions and passions in each moment our lives provide. This living channel of grace brings to mind the life-giving river that flows from the living sanctuary of God, “the river that refreshes all, that brings health and healing to all living creatures that immerse themselves in it” (Ez 47:9). Or, as Ven. Rougier reflects, “I put myself in your presence, most beloved Father, and I saw that eternal river. Did I see it? Or was it my imagination? Was it you, the fountain of the divine? I wish to be all yours, and love you passionately in time, and in eternity; because I am a drop of that river…Because I am truly your son, aren’t I, Father?” 11 For ordained priests then, Loving Attention provides a simple and natural rhythm for living their priesthoods in a spiritually empowering manner for themselves, and for those they are called to serve.

On first glance, the practice of Loving Attention to God seems quite similar to ideas already suggested by the Jesuit, Fr. Jean-Pierre de Caussade (1675-1751) in his book, Abandonment to Divine Providence. He states that: “Holiness is produced in us by the will of God and our acceptance of it. It is a matter of changing our attitude towards these things, to say, ‘I will’ and in this obedience become one with God.” 12 Although Fr. de Caussade mentions the human heart, the primary manner to growing in likeness and union with God was through a rather dry surrendering of oneself to God’s will that one encounters in the demands of the present moment. Likewise, Br. Lawrence (c. 1614-91) comes closer to the paradigm of Fr. Felix in his spiritual classic, The Practice of the Presence of God. Brother Lawrence describes coming to a “habitual sense of God’s presence…by driving away from my mind everything that was capable of interrupting my thought of God” 13 which allowed him to have a “simple attention and general passionate regard to God, and that stirred greater sweetness and delight than that of an infant at the mother’s breast.” 14 Although Brother Lawrence still focuses on the mind, he begins to insinuate that this simple attention to God involves more than the intellect.

For some, Loving Attention, as an attitude of prayerful living, sounds quite analogous to St. Ignatius of Loyola’s exercise of the daily Examen. This Ignatian exercise fosters a capacity to recognize the Lord’s spiritual invitations to us in the midst of living, and, thereby, find God in everything. There are many parallels between the two practices which Fr. George Aschenbrenner seems to confirm, in his classic article, “Consciousness Examen.” He describes St. Ignatius’ proposal of daily examination as a two-part proposition of structuring a prayer experience, twice a day, to review the spiritual movements, or highs and lows, of the day which facilitates a greater spiritual sensitivity and order in living. 15 While both Ven. Fr. Felix, and Ven. Concepción, were formed by Ignatian spirituality, they take the practice of spiritual attentiveness to God, and utilize it as a means of expiation, or of obtaining graces, making an offering of self for others. In this light, Fr. Felix admonished novices, “Make an examination of conscience concerning your Loving Attention to God, for it is, perhaps, the best examination that we can make, and the most practical.” 16 Their focus is not so much in simply ordering the interior movements, but to do so as a movement of intimate love for God and others, as a movement of priestly love.

To Ven. Fr. Felix Rougier, Loving Attention to God was “the quickest, most direct and certain way of becoming holy.” 17 It was the by-product of being a lover of God, and an avenue to developing an intimate love relationship with each person of the Trinity. Through its practice, he made his own life an offering of love for the salvation of others. Writing to someone who failed to understand his perspectives, he wrote that Loving Attention is: “Falling in love with God. It is a passionate love. It is not being able to forget about Jesus, not even for a moment. It is a strong passion for Jesus, the Father, and the Holy Spirit.” 18 Recollection in God, for Fr. Rougier, involved all the energies of the person, becoming much like the single-hearted focus of a man and a woman in love. Once in a dialogue with a novice who had been engaged before coming to the community, Fr. Felix told him:

Have you ever had a girlfriend?

Yes, Father, responded the novice.

Did you love her a lot?

Yes, Father.

Did you think of her often?

Yes, Father.

Well, put God in her place, and this is Loving Attention to God. 19

Ven. Felix voices the conviction that this prayerful experience of union with God in the moment (Loving Attention), draws all parts of the human person—body, mind, and soul—into the transforming light of Jesus’ own heart, so that the human service they offer to others channels God directly to those they serve. This allows the energies of the whole person (i.e., the priest) to become an almost “sacramental avenue” for God, in reaching out to his people. Furthermore, according to Ven. Felix, nothing ultimately gets in the way of the practice of Loving Attention, short of our own human weakness. He often told his priests: “Loving Attention to God can always be done, even in the midst of a life as busy as yours. Love is the only thing which makes this life of prayer possible. Love does not forget. Love unites.” 20 Therefore, by loving in this way, in sync with the love of God, the priest grows in human maturity as a spouse to the Church.

If we examine Fr. Felix’s perspective, we see that his approach coalesces easily with much more recent ideas on love and service, for instance, those offered by Pope Benedict XVI in Deus Caritas Est., where he says: “It is neither the spirit alone nor the body alone that loves; it is man, the person, a unified creature composed of body and soul who loves. Only when both dimensions are truly united, does man attain his full stature.” 21 For Father Felix, (and Pope Benedict XVI, too) recollection and ministry are responses of the entire person that loves God, that also makes him capable of loving others, no matter the obstacle or cross. Love is the light and power that strengthens and impassions him, so he can advance when all seems dark and unpredictable.

We see this in Fr. Rougier’s own life. In 1914, when nearly all churches had been confiscated and closed by the Mexican government, and many priests and sisters had already been martyred for the faith, Fr. Rougier landed back in Mexico. After a ten-year exile in France, he arrived to move ahead with his original mission: to found this new congregation of priests, the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit, with his spiritual friend, Ven. Concepción Cabrera de Armeda (1862-1937). 22 However, during Fr. Felix’s first afternoon back in Mexico, the Archbishop of Guadalajara, Francisco Orozco Y Jimenez, greeted him, shaking his finger at him. The Archbishop said: “Father, we are not now in a position to found anything, nor even to work; almost all the bishops are in hiding or have fled the Republic. Come to Havana with me on this next steamer; there I will help you. At this very moment, our nation is dying.” However, Fr. Felix took this as a confirming sign of God’s providence, and immediately shared with the Archbishop an insight that he had received ten years earlier, during his first tenure in Mexico. The Lord had shown Ven. Felix that “the new foundation would come about at the precise moment that the nation was in its death-throes.” 23

We may ask, then, how did Fr. Rougier strengthen himself to confront such odds? How did he form his priests to minister, when they were dodging martyrdom at every turn? It was to find God with them in every detail and every moment, like a faithful friend, loving them each moment, and giving them everything that they needed. It was this intimate awareness of God that moved their own hearts and minds, with the radiance of Christ’s own love, transforming Fr. Felix and his priests. It propelled them towards the Cross in these drastic times during the Mexican Revolution. One day, walking down the street, a member of the new Congregation frantically approached Fr. Rougier, announcing that the army had just come, taking four of the community’s houses, leaving the priests out on the street. Fr. Felix replied, “Four houses? Well, Thanks be to God there were four houses, and not ten.” 24 While this response may be surprising, hinting at some emotional minimalism, in truth it shows how Fr. Felix had grown accustomed to seeing God in each moment, even those moments infiltrated by the Cross.

Fr. Rougier, most likely, would tell priests of today how to confront challenges of ridicule, discouraging or routine priestly lives, overwork, suffering rejection or suspicion: let the living radiance of Christ’s love embrace and empower you through the simple practice of Loving Attention to him. And, by it, swim in the “Living Waters that flow from the sanctuary.” 25

Ven. Rougier viewed the practice of Loving Attention as a developmental process of learning to center oneself, and love God in each moment, thereby becoming a saint. He suggested that a person begin this new practice of attending to God by actively focusing (and refocusing) one’s glance towards him during the day, through acts of the will that are motivated by love for God. His recommendation was “to step out of bed, first thing in the morning, with the intention to place yourself under the gaze of the Most Holy Trinity, and to create for yourselves this atmosphere, in order to spend your whole day there.” 26 This capacity grows as one learns to quiet his or her faculties, so one can sense and correspond to the movements of the Holy Spirit within oneself in the moment. Father Felix taught that the perfection of our acts was judged by the degree of our union with God, which motivated these actions. He preached slowing down, living more intentionally, in the presence of God in order to become available to the One that we love. He liked to say that, “Ordinary things done well (or with love) make saints.” 27

Likewise, Ven. Concepción Cabrera de Armida, his spiritual friend, and co-founder of the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit, also attempted to live lovingly attentive to God, through her ordinary experiences as a wife and mother. To impregnate her life with this dynamic sense of God, she regularly moved a chair over to where she was working in her home, a chair that would be for Jesus, as a reminder to her that in everything, the Lord was with her, gazing upon her. This interior discipline became for Ven. Concepción, a simple means of becoming available to respond to her Beloved.

For Fr. Felix, living in intimate and growing union with God, also entailed developing and exercising the virtues during prayer time, or as he “worked, walked and talked.” 28 He insisted that novices embrace opportunities that helped them develop purity of heart, and obedience to superiors, in the needs of the present moment. His example showed them that a love for, and practice of, silence, or recollection, ignited all good habits and action throughout the day.

Consequently, the co-founders of the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit encouraged frequent spiritual communions with Jesus throughout the day, which included repeating simple loving ejaculatory prayers to Jesus, like Father Felix’s favorite mantra: “God, God, God in everything and for everything.” 29 Moreover, both Father Felix and Mrs. Cabrera recommended utilizing the ordinary challenges of the day as opportunities to make small sacrifices to Jesus, for one’s sanctification, and others. For them, the combination of prayer, sacrifice and docility of heart became a combustible spiritual mixture, a “fuel that ignites the living fire of love of God” 30 and the living image of Jesus, the very life of the priest.

This leaves a real awareness that the active pursuit of God, through Loving Attention, is actually “a preparation for arriving at passive Loving Attention, a special grace that God gives ordinarily to generous souls.” 31 In a letter to one of the first Missionaries of the Holy Spirit, someone who Fr. Felix trusted deeply, he described his experience of passive Loving Attention: “My soul only has good desires and longings, and this presence of God, which, by his mercy and without merits on my part—rather quite to the contrary—does not leave me.” 32 Likewise, the spiritual diary of Ven. Concepción describes this infused Loving Attention as a great gift, something given to her from God. Even as she goes about washing clothes, and caring for her children, and in everything, God is pursuing her, drawing her human will, intellect and affections into union with him. She says:

Now, I do not work at quieting my senses and faculties, rather they themselves are put in order. The Lord takes care of this. I live my natural life as if I were not living it, because my life is him. I do not know how to explain it, but his presence does not leave me and he continually prods me to make my acts supernatural. 33

It seems that once the person shows his fidelity to God, by choosing to find him both during prayer and ordinary life, God often begins to gather the person into his living radiance or presence by his own initiative.

In addition, the Lord is particularly consoled by the practice of Loving Attention. One afternoon, while she worked in her home, Ven. Concepción Cabrera de Armeda received the Lord’s words clearly in her heart:

Concha: Look, to be forgotten hurts me more than the sins of the world because, to be forgotten, comes from my own, and this hurts the sensitivity of my heart. Do not forget me, and do not let yours forget me, because forgetting me implies or shows your ingratitude, which is what most pierces my heart with thorns. Make this offering in reparation for the culpable neglect which lacerates my heart of love. 34

These loving words that Concepción sensed from the Lord, help us understand how moved the Lord is by our simple human efforts of noticing him, as we minister to others. He shows that our Loving Attention to him is a powerful and priestly response, drawing graces to others, imprinting his image upon us, in all our faculties.

Besides attempting to live all of life as prayer, Father Felix promoted two methods of structured prayer that helped facilitate the development of this passive or infused loving awareness of God: meditative reading and affective prayer. He counseled that when you read scripture or religious texts, “Read them slowly and savor what you read. Interrupt your reading from time to time to make acts of affection to God.” 35 Reflecting and meditating on the things about God, with the heart engaged, ordinarily leads to, what Fr. Felix considered as affective prayer. For Fr. Felix, prayer was not activating simply the will and intellect, and reflecting at length about God, but rather engaging ones heart, and loving God, in the midst of learning about him. He would say that, when you pray, “Let your heart speak. Talk to Jesus with great trust.” 36

After talking openly with Jesus in great trust, priests can more easily entrust themselves to him, resting in his living presence, finding him present to them as they race to another evening meeting, or listening to an angry or needy parishioner, or opening the newspaper to read a disturbing story. However, some may wonder, if in resting in God, they are idle or wasting time. To someone who was concerned about this, Ven. Rougier confided: “Souls who radiate God, or who love Him passionately, are never idle. Focusing on God, even without saying anything, is a great act of love. The end purpose of all prayer is union.” 37 This very union with God, that Loving Attention helps cultivate, motivates the priest to love his flock “as Christ loved the Church and sacrificed himself for her to make her holy” (Eph 5:26). By loving in this way, the priest lives a “life that is full and worthy of his nature as a human being and harnesses for his own welfare (and that of the Church) the immense resources of the modern world.” 38

In summary, Fr. Felix would counsel priests today to turn constantly towards Jesus, who “like a sunflower, always turns toward the sun until sunset.” 39 He would encourage priests to practice Loving Attention, considering it a means to truly fall in love with Christ, whereby, they learn to live, to move, to have their entire being immersed in the living radiance of God, alive within and around them. Then, they can catch a glimpse of him, as they meet the challenges of the day, no matter what it holds, offering their lives as a living sacrifice for themselves, and the flock they tend. As they live this approach more faithfully, Jesus steps in to draw them deeply into himself, by ways that no longer require their effort. Love draws all their human faculties and human energies towards God, in the practice of Loving Attention.

In this light, Loving Attention offers us all, and especially ordained priests, an answer to the “ever recurring questions which people ask about the meaning of this present life, and of the life to come, and how one is related to the other” 40

- Gaudium et Spes, §4. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, §1. ↩

- Fėlix de Jesŭs Roguier, Autobiography (Mexico: 2009) 28. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, The Spirituality of Fr Felix Rougier, M.Sp.S., Loving Attention to God, trans., Thomas Shafer (Mėxico: 2011) 10; hereafter, Spirituality. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 17. ↩

- Fėlix de Jesŭs, Collection of the Letters to the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit (Letter dated December 17, 1925); hereafter, Letters. ↩

- Private conversation with Fr. Domenico Di Raimondo, the Provincial Missionaries of the Holy Spirit for the United States, April 1, 2011. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, §1. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, §4. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, §3. ↩

- Fėlix Rougier, M.Sp.S. Letters (undated). ↩

- Jean-Pierre De Caussade, S.J., Abandonment to Divine Providence (New York: Doubleday Books, 1975) 27 and 35. ↩

- Brother Lawrence, The Practice of the Presence of God (Old Tappen, NJ: Spire Books, 1958) 31 . ↩

- Brother Lawrence, The Practice of the Presence of God, 37. ↩

- In his essay, “Consciousness Examen,” Fr. George Aschenbrenner, S.J., states that, “The presence of the Spirit of the Risen Jesus in the heart of the believer makes it possible to sense and to hear this invitation and, thereby, to order ourselves to this revelation,” Review for Religious, vol. 31 (1972) 14-21. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs, Letters Letter to A. Perez (dated June 26, 1927), and to Novices (dated March 30, 1926). ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 19. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs, Letters, Letter to a Daughter of the Holy Spirit (dated June 23, 1924). ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs , Platicas Espirituales (Private Edition {1929}: 1966) 166. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs, Letters, Letter to Fr. M.Lira (dated May 18, 1927). ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, §5. ↩

- Ven. Concepción was a wife, a mother of nine children, a mystic, a founder of the “Works of the Cross,” and a powerful spiritual writer, that some claim rivals Thomas Aquinas in her theology, spirituality of the Cross, and related themes. ↩

- Fėlix de Jesŭs Roguier, Autobiography, 38. ↩

- Private conversation with Fr. Domenico Di Raimondo, the Provincial Missionaries of the Holy Spirit for the United States, April 1, 2011. ↩

- Ezekiel 47:12 ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 28. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 32. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 10. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs , Platicas Espirituales, 83. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 33. ↩

- Jesŭs Maria Padilla, Spirituality, 35. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs , Letters, Letter to Fr. F. M. Alvarez (dated July 15, 1925). ↩

- CCA AC Vol 22, p 342. ↩

- CCA 46,87 Oct. 20, 1925. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs , Letters, Letter to Gauadalupe Zavala. ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs , Letters, Letter to J Castro (dated March 1917). ↩

- Fr. Fėlix de Jesŭs, LaCruz , Mexico,1927, p229-230 Response to someone who wanted advice on prayer. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, Chapter 9. ↩

- Fėlix de Jesŭs Roguier, Platicas Espirituales (Aug 7, 1932) 43. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, §4. ↩

What a beautiful article! How absolutely appropriate for these times, when those striving for holiness easily feel overwhelmed by the world swirling around them. I thank the author for the research and for writing so ably, and above all for the spirit radiated through the article.

I liked this article very much: it serves a great purpose well. I disagree, however, with the dismissive way in which the author deals with Fr. Caussade’s writings on giving oneself up to God. After all, it was by giving herself up to God that Our Lady served humanity and God most: Behold, the handmaid of the Lord! I think that “Loving Attention” is simply a continuation of the practice of giving oneself up wholly to God: body, heart, and mind.

Dear Ryan,

I appreciate your comments. This discussion on “Loving Attention” is not meant to dismiss the contribution of Fr. Caussade or to dismiss his great desire to offer himself to the Father. The main difference that I see between Fr. Caussade’s work and that of Fr. Felix Rougier is the emphasis on affectivity of the practice of offering oneself, or the whole hearted passion of cultivating this sense of God in every moment.