For Sunday Liturgies and Feasts

Homilies for November 2012

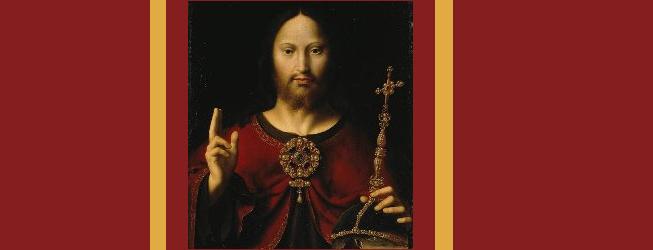

Christ, the Savior by Geranimo Bobadilla 1620-1680

Christ, The Great High Priest

Purpose: The second reading should be used occasionally when it presents an important catechetical topic. In the context of the Year of Faith and the New Evangelization, the topic of the priesthood is of critical importance. Many people simply do not understand the indispensible role that the priest has in our salvation. The “Letter to the Hebrews,” with its contrast of the old and new priesthood, offers some valuable teachings. First, it reminds us that Jesus Christ is the only True Priest, a point overlooked by Catholics and Protestants alike. It also teaches us that the men it involves remain weak and under-qualified to the task. While this is a stumbling block for some, the humanity of the priest should nevertheless be seen as a bridge giving us access to the spiritual riches in Christ.

31st Sunday in Ordinary Time—November 4, 2012

Readings: Dt 6:2-6 • Heb 7:23-28 • Mt 12:28b-34

Among my favorite tales of St. Jean Vianney are his encounters with the devil. The miserable Grappin tried everything: name-calling, setting his bed on fire, vomiting on his floor—yet, nothing seemed to phase this vigilant servant of God. In fact, St. Jean came to welcome the devil’s appearance, since it always meant that he could expect a major penitent to come to confession the next day.

When I read about St. Jean’s life though, I am even more comforted as a priest. St. Jean was frail, not terribly bright, and not terribly gifted as a speaker. Yet, it was precisely this unlikely man who ransomed hundreds of souls daily for Christ. The message is simple—the priesthood of Jesus Christ is an enormously powerful gift. It sounds through our human weakness, manifesting the person of Christ himself to sanctify others.

We don’t always get to spend much time on the epistle, but today it is worth considering this important doctrine of the Church, coming through Hebrews. “Jesus, because he remains forever, has a priesthood that does not pass away…he is always able to save those who approach God through him, since he lives forever to intercede for them.” The Scripture contrasts the inadequacy of the old priesthood—human, limited, weak, unable to save—with the new. This form of priesthood foretold the coming of the One Priesthood of Christ. Since that time, this One Priest continues his ministry on earth, through the hands of men called by God. Some mistakenly think that Catholicism denies Christ as our one mediator because we multiply priests. Yet, the Church has always taught that we have but One Priest. As Blessed John Paul II taught, the priest “prolongs” the humanity of Christ so that he can exercise his priesthood in the flesh. Thus, when a priest says, “This is My Body,” it is Christ himself saying the words, and effecting the sacrifice. When a priest says “I absolve you from your sins,” it is Christ who forgives in the sacrament.

The Letter to the Hebrews contrasts the old priesthood with the new as a commentary on the efficacious power of the New Testament sacraments. Implied, between the lines, is that we should not be “fooled” by the apparent unworthiness and weakness of the minister. Just as in the old law, priests today are men “beset by weakness.” Yet, in spite of this, “he is taken from among men and made their representative before God.” One is confronted with an amazing paradox: men beset by weakness, made to represent men to God, and God to men. Be assured, this is a call far beyond the powers and ability of any human being!

In working with the vocations office, often I am met with young men who resist the call to serve as priests, claiming that they are unworthy, or do not have what it takes. I am quick to remind them that the history of God calling people to serve him in ordained ministry is a history of human weakness. From the earliest days, when called by God, Moses protested: “Who am I? Suppose no one will listen to me? If you please, Lord, I have never been eloquent, but I am slow of speech and tongue!” God’s reply: “I will be with you. It is I who will assist you in speaking, and will teach you what you are to say.” Jeremiah, the prophet, had a slightly different excuse: “Lord God, I know not how to speak; I am too young!” I have tried this excuse myself, to no avail. God says: “Say not, ‘I am too young.’ Have no fear before them, because I am with you to deliver you. See, I place my words in your mouth.” And, then there is Peter. Falling to his knees, he shouts: “Depart from me Lord, for I am sinful man!” The Lord replies: “Do not be afraid. From now on, you will be catching men.”

Even today, many are being called, but find themselves unable to answer, either because they do not think they have the gifts, or because they are too young, or too sinful. In short, they fear failure. They are deeply aware of their human frailty. But, in the Scriptures, we learn to rejoice in our weakness. At every turn, we encounter men who are too weak to faithfully serve God as priests. At every turn, we encounter the marvelous fidelity of God, who gives what they need to serve! I once saw posted on a Church sign outside: “God does not call the qualified; God qualifies the called.” Or as Hebrews says in another passage: “No one takes this honor upon himself, but only when called by God.”

Still today, if you visit a seminary, you are not likely to find a house of angels, too holy and unapproachable to relate. Rather, you will find men who are weak, unqualified, and unworthy. We priests are men who put on pants, one leg at a time. We fall into sin like everyone else. We get sick and injured. We get tired (and, yes, sometimes cranky). We go to confession like everyone else. However, these human limitations are precisely what come with our God’s plan to keep his one priesthood accessible.

The priesthood is yet another example of Our Lord’s sense of humor—he calls as many unqualified men as he can, and then, empowers them with gifts beyond imagining! To quote St. Jean Vianney: “O how great is the priest! If he realized what he is, he would die.”

Dear people of God, pray for your priests, for we are men “subject to weakness,” and we’ve been entrusted with an impossible task. To you young men being called but who are afraid to answer, I repeat the words of Our Lord to his chosen men of old: “Do not be afraid…I will be with you…I will assist you.”

(Related sections from the Catechism of the Catholic Church: §1539-53; 1585-89.)

Called to Saintly Stewardship

Purpose: Every pastor knows that the homily on money must be pitched with great care. In my experience, people do not give to programs and projects that do not appear to have value. Bearing in mind also that many people have a materialist and too-human approach to stewardship, it is crucial to bring out the supernatural and spiritual purpose that God attaches to it. The context in both the first reading and the Gospel are key to revealing the divine plan for our parishioners’ offertory giving. Reminding them that the New Evangelization has many needs that require financial support can be effective in helping them to see their responsibility before God.

32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time—November 11, 2012

Readings: 1 Kgs 17:10-16 • Heb 9:24-28 • Mt 12:38-44 (or Mt 12:41-44)

As a young associate pastor, I had the privilege of being able to talk about money without being accused of trying to get into peoples’ wallets. Sadly, at the mention of the word “stewardship” from a pastor, many people automatically start to groan. This is because we often fail to see the profound spiritual purpose behind our charitable giving.

In our first reading from the Book of Kings, we must look at the context to see that this is not merely a story about a generous lady. The context is this: Elijah is one of only a handful of people in Israel who has not sacrificed to Baal. The leadership in the nation suffered a very radical change almost overnight. The evil king Ahab opened the door to pagan idol worship throughout the kingdom. As punishment, God sends a drought, and the resulting economic hardship. Elijah’s mission is to call God’s people to conversion, to eradicate the moral depravity, and thus end the drought. Into this climate, God calls forth this random poor, starving widow to give aid to the mission of Elijah. Her offering, however small, is in fact her very life. She is expected to die as a result of the gift, but it is absolutely necessary if Elijah is to succeed in bringing God’s people back.

Only in this context must we understand stewardship, and not in any other! We do not give just because the Church parish needs more stuff. We give because it is a vital part of the Christ’s mission of Salvation. The offertory of the parishioners plays an indispensible role in saving souls!

Look at our nation and culture today. Is it not sliding into paganism and moral depravity? God’s true followers are fewer, and we are falling on hard economic times (not likely a coincidence). We have been called to give at an hour that is very demanding—it demands, not just what we can afford from our excess, but our entire livelihood!

The Gospel also has an important context that should not escape our notice. The scene takes place at the Temple. Scripture tells us that the collections taken at the treasury are to be used to repair the Temple of God. As a pastor, I could take the approach of asking for money, citing the different physical plant needs of the parish —the new cry room, or the leaking roof, or new air-conditioning, etc. But there is much more to the “temple” than the building. Jesus, prior to this episode, had made an amazing claim:“Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” The “temple” is his body! The Church—the Body of Christ—is the temple in which our donations are used for building up and “repairing”. The Church’s true needs are not material. They involve saving souls. Some of the most costly services of the diocese, for instance, are directly related to the New Evangelization. The news and television service, the subsidy for the retreat center, the annual youth conference, the formation of future priests, all of these are just some of the important needs. All are tied directly to the salvation of souls, all depending on the generosity of parishioners.

It is important to note, however, that what Jesus wants is not merely dollars, but our “whole livelihood.” What follows this scene in Mark is Jesus’ arrest and passion. He is offering himself in sacrifice. He is setting an example before us of the true nature of stewardship giving. He gives his life to the cause, as we must also do. We can cite plenty of other examples from Scripture here: Abraham gives his only son, Abel offers his very life along with the portion of his flock, etc.

“So Father,” you might ask, “Why do I need to give money? Isn’t it enough to be a good Christian?” It is true that you can sacrifice in other ways, besides money, but if we’re honest, we know that the sacrifice of one’s treasures is the clearest evidence of giving one’s “livelihood.” Money goes straight to the heart of the matter. It has great symbolic value which is far greater than any other thing we sacrifice. It represents the ability to survive, the freedom to choose what I want, independence, self-reliance. Therein lies the danger. Love of money is the root of all evil because it makes us less dependent on God. Notice the counter-example of the scribes in the Gospel, who think they have it all figured out.

To save us from idolatry, God asks that we sacrifice our money. In truth, God does not need more money. Mother Teresa would often say to those who worried about the order’s finances: “Don’t worry. God has lots of money!” What is more important to God is his desire to save us from the snares of wealth by having us invest it in something other than ourselves.

Let’s speak frankly for a moment. It is entirely possible that our parish could misspend the hard-earned money of its parishioners who donate it in good faith. There is no guarantee that it will be used to build up the kingdom of God. That is the risk we all take in a Church full of sinners. Nevertheless, be reassured that God will repay you anyhow. It is, after all, his problem if we misspend it.

At the hour when the kingdom of God needs it most, God sends a poor depressed woman to make an offering at great risk to her life. The result is the salvation of an entire nation. Today at this hour, when the Kingdom of God is battling against the culture of death, God sends you, asking you to take a risk. You may not see the results, but I am willing to bet it will prove to be at least as important. And besides, Jesus adds, “your reward will be great in heaven.”

(Related sections from the Catechism of the Catholic Church: §1351;1438; 2043.)

Stay Awake as the Days Darken!

Purpose: Each year the Church’s liturgy gives us a meditation on death. As pastors, we would be remiss if we did not take this opportunity to reflect on this mystery with our people. All of the spiritual writers place the topic at the forefront of their treatises, since our conversion to Christ typically begins with “attrition”—a beginning movement away from sin in the face of certain death, and the prospect of an honest judgment. The relevant sections of the Catechism, and the lives of the saints, are full of good material that can easily fill your homily this weekend.

33rd Sunday in Ordinary Time—November 18, 2012

Readings: Dn 12:1-3 • Heb 10:11-14, 18 • Mt 13:24-32

The days are getting shorter, the air is cooler, trees are shedding their leaves. We are in a season of death. Every year at this time, nature preaches a little sermon to us: you will not be here very long! Our liturgical cycle takes note of this as well and calls our attention to it.

Our liturgy today reminds us to “be vigilant at all times and pray that you have the strength to stand before the Son of Man.” We must remain conscious of the reality of death, and what this means for our loved ones who have gone before us in death. St. Ambrose tells us we should have “a daily familiarity with death.” He is not the only saint who speaks like this. St. Benedict would say: “keep death before your eyes always.” St. Philip Neri had a brother who kept a skull in his room with the inscription: “O thou who lookest now on me, as thou art now, I once have been; as I am now, thou soon wilt be.” Recently I read of a Church outside of Prague whose interior was built entirely of bones, including the altar, pulpit, and chandelier. This seems morbid to us, but for a people who lived through plagues and wars, they learned to keep the reality of death before their eyes. They were practicing vigilance.

Why must we think of such things? Because, as Jesus tells us today, “of that day or hour, no one knows.” In the context of the Gospel, Jesus is describing the hour of his return. But in truth, that hour will meet us when we face death.

At the same time, we must remember that we do not belong to this world. Our stay here is temporary. We are destined for something far greater. St. Paul tells us: “Life is Christ; death is gain.” The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that it is in regard to death that man’s condition is most shrouded in doubt. Yet, the Scriptures help us to see that Christian faith adds a very deep meaning and great hope to this mystery.

One way the Scriptures do this is through the image of sleep. The prophet Daniel today speaks of “those who sleep in the dust of the earth.” The Gospels, and St. Paul, also use “sleep” as the preferred word for death. The image of sleep is actually a very accurate depiction of death; it is not just flowery language. Think about how you fall asleep at night. You shut your eyes, and you fall out of consciousness, and in an instant, you awake to a new day. Scientists are not able to fully explain why we sleep—it remains a mystery. Perhaps, the Lord has given us this bodily reality as a rehearsal for what is to come. Even the Church’s night prayer is written in this tone, comparing the ending of the day with the ending of our lives.

What sleep implies for the Christian is that death is temporary; it is not the end. There will be a bodily resurrection. The Church’s Mass for the Dead says: “Life is changed, not ended.”

I would like to mention a few points about death. First, death is not natural, contrary to popular belief. Scripture tells us, “God did not make death,” and “the wages of sin is death.” Death clearly was not in the plan of God in the beginning. Yet, St. Ambrose tells us: “God prescribed it as a remedy.” What he means is that after sin enters the world, immortality would have been a curse. It was an act of mercy that God cut our earthly lives short.

Not only is it a remedy, but death is also our redemption. Christ uses it as an act of love for the Father, in complete obedience to him. We, too, are called to embrace the will of the Father at the hour of death. We must be ready to make an act of total obedience to him when he calls. This is the meaning of our Christian baptism, which is a sacramental death, an anticipation of our physical death. Then, Christ will perfect his work of redemption which began at baptism.

For this reason, the saints viewed their own deaths with great confidence. St. Ignatius of Antioch desired to be devoured by beasts in Rome, and begged his friends not to stop the proceedings. St. Therese of Lisieux said on her death bed: “I am not dying, I am entering into Life.” St. Teresa of Avila said: “I want to see God, and in order to see him, I must die.” St. Francis of Assisi called it “Sister Death.” Such is the hope we have from the teaching of our Lord, and the peace of a clear conscience.

We read in the Imitation of Christ, “Every action of yours, every thought, should be those of one who expects to die before the day is out. Death would have no great terrors for you if you had a quiet conscience … Then why not keep clear of sin instead of running away from death? If you aren’t fit to face death today, it is unlikely you will be tomorrow.”

Are you fit today? St. Francis de Sales recommends an interesting spiritual exercise. Imagine you are on your deathbed, never to recover. Consider that there will be nothing left of you. Even those attending your funeral will eventually move on and forget you. Consider at the moment of death, your soul will either go right or left. Which way shall you go?

Dear friends, remain vigilant. Prepare today for what will come. For if we are unprepared, we will never know the truth that “life is Christ, and death is gain.”

(Related sections from the Catechism of the Catholic Church: §164; 1006-14.)

Christ, The Servant-King

Purpose: It is worth our time to preach about the sacrament of penance several times during the year. The need for a revival of this sacrament was cited at the Synod on the New Evangelization as a “sine qua non” for restoring faith. The classical idea of a king can be useful in highlighting the importance of confession for our people. Kings can issue an irrevocable pardon, keeping their courts open to the people for this purpose. The Gospel, with its context from the passion account of John, reminds us that our King is approachable, indeed, thirsting to dispense pardon in his court of mercy.

Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe—November 25, 2012

Readings: Dn 7:13-14 • Rv 1:5-8 • Jn 18:33b-37

The readings for this feast of Christ the King open up with a vision of judgment. The Son of Man takes his seat in heaven—a seat of authority in which he will judge everyone. He tells us in John’s Gospel: “He has given all judgment to his Son” (5:22).

We typically think of the king as simply a supreme lawgiver and executive. We forget, however, that before the dawn of modern nations and democracy, the king was equally a symbol of clemency, that is, mercy. The king had the power to issue pardon. His was the final court of appeal. The king, and only the king, has the power to absolve high crimes in the realm! I might add, in many civilizations, this king was surprisingly approachable. Thus, we read about St. Paul appealing to Caesar as a citizen. It was said of the reign of Louis XIV in France that any French citizen had recourse to the king, even if he were a slave.

If Christ is our King, let us not be afraid to ask pardon of him. For Catholics, this is done in the sacrament of reconciliation. This sacrament was established out of our Lord’s desire to maintain his court of clemency—the final court of appeal in which any citizen of heaven could obtain pardon.

Our Gospel today contains several twists of irony. One is the presence of Pilate, the earthly authority. He does not have the faith to see that he stands in the presence of the one from whom his authority derives. This same Pilate will later inscribe the charge above Jesus’ head: “Jesus Nazarene, King of the Jews.” This charge is not simply a taunt; it reflects the official verdict that is to be promulgated throughout the land. Written in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, it would, in effect, name Christ as king in civil law, common circles, and religious practice. Indeed, as the Scriptures today profess, Christ Jesus is “King of Kings,” that is, “Ruler of the kings of the earth,” and “all peoples, nations, and languages serve him”.

If they are to be legitimate, kings must be just. They must be men of the law, who judge impartially, according to the truth. Jesus says: “I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth.” Christ is the alpha and omega. He was in the beginning, and inscribed laws into the order of the universe, laws that guard peace and harmony. Humanity, though, has been in revolt since the fall—revolution, high treason against the King. This is a capital crime. But, our King, who is also our God, would rather die himself than see us perish.

So, Our King takes the penalty of high treason upon himself. The cross was reserved only for traitors. It, therefore, shows us what our deeds deserve. Recall for a moment the horrors inflicted upon our Lord: the beatings the scourging, the nails, the thorns, asphyxiation, betrayal. These are our sins reflected. The children’s books by C.S. Lewis, Chronicles of Narnia, depict this exchange well. Aslan, the just and noble lion, who submits to torture and execution, moves the hearts of young and old alike because of his innocence.

The truth is this: our mortal sins deserve the cross, and afterward, eternal death. Even our venial sins deserve at least the scourging. Yet, Our King settles the score himself. Our King then sends a peace delegation to all of his subjects in revolt. Here, we see the role of the priesthood—the King’s official “delegates.” These are the terms of the King: I will pay your penalty; you can obtain a full pardon. Confess your sins, be reconciled with the minister who acts in my name. Turn in your weapons, lay down your arms, and promise never to take them up again in revolt. This is what happens when we approach the sacrament of mercy.

Many have difficulty with confessing to a priest. After all, only God can forgive sin. Only the King may pardon. Yet, we all know that kings never act simply by themselves. Neither does Christ. Isaac of Stella, a twelfth-century monk, living at the height of the rule of the English crown, compares the Church of God to a queen. He writes: “The prerogative of receiving the confession of sin, and the power to forgive sin, are two things that belong properly to God alone. Since only he has the power to forgive sin, it is to him that we must make our confession. But when the Almighty wedded a bride, who was weak and of low estate, he made that maid-servant a queen. She had been born from his side and, therefore, he betrothed her to himself. And, as all that belongs to the Father belongs also to the Son, so also the Bridegroom gave all he had to the bride, and he shared in all that was hers. Therefore, she, too, has the prerogative of receiving the confession of sin, and the power to forgive sin, which is the reason for the command, ‘Go, show yourself to the priest.’”

If there is a king, there is also a queen, who shares his full authority. Since Christ wedded his Church, Christ is no longer merely the person of Jesus. He is Christ the King, the one who forgives, who is both head and members—the whole body of Christ, the Church. To quote Isaac of Stella again: “The Church is incapable of forgiving any sin without Christ, and Christ is unwilling to forgive any sin without the Church. What God has joined together, man must not separate!”

Dear friends in Christ, rejoice, for your God is King. Rejoice because he has paid the price for our high treason. Rejoice that your King exercises the power to pardon sin when we willingly approach his delegates.

(Related sections from the Catechism of the Catholic Church: §541-43; 668-74.)

Thank you Fr Nathan.