The term “social justice”… is the key term and concept of Catholic social teaching … with all the other aspects of the Church’s social doctrine—the principle of subsidiarity, the just wage or the right to private property—are related to, and rely, on the existence of social justice.

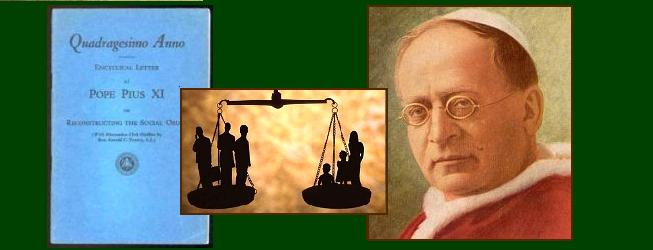

The term “social justice,” though common enough today, is little understood by most of those who use it—whether they consider themselves friends and practitioners of social justice, or they regard it as a suspect term of probably socialist origin. But the term does have a precise meaning. That meaning and the significance of this concept of justice, were carefully explained by Pius XI, the pontiff who introduced it into the corpus of Catholic social teaching. In many respects it is the key term and concept of Catholic social teaching. All the other aspects of the Church’s social doctrine—such as the principle of subsidiarity, the just wage or the right to private property—are related to social justice, and rely on the existence of social justice. Pope Pius, who reigned from 1922 to 1939, introduced the term into Catholic teaching in his encyclical, Studiorum Ducem (1923). He later made extensive use of it in two important social encyclicals: Quadragesimo Anno (1931) and Divini Redemptoris (1937). But, before taking a close look at the exact meaning of social justice, let us try to clear away some confusions over justice itself, especially as contrasted with charity.

To illustrate the frequent confusion about the meaning of social justice, and, indeed, about justice in general, one sometimes hears the activity of working in a soup kitchen cited as an example of social justice. However laudable such work is, it is not a work of justice, social or otherwise, but rather one of charity. Thus, the first distinction we must make is between “justice” and “charity.” What is justice then? Thomas Aquinas takes as the settled definition of justice that of the Roman jurists. 1 According to them, justice is “a perpetual and constant will of giving to each one his right {jus}.” Plato had already referred to justice under similar terms in the Republic (331e), attributing the definition to Simonides, a poet who died ca. 468 B.C. As we will see, there is more than one kind of justice, but common to all of them is this notion of rendering what is due, i.e., of what someone has a right to. As Josef Pieper put it: “The hallmark of all…forms of justice is some kind of indebtedness….” 2 Charity, on the other hand, although it can be a duty binding on someone, and even a duty toward a particular person, differs from justice in that its “violation does not involve injury, in the technical sense, and does not call for restitution or punishment.” 3 Often, duties of charity are not directed towards anyone in particular. For example, my duty of charity to give away a certain amount of my goods, while binding in conscience, does not oblige me to give to any particular person. No one particular poor man ordinarily has a claim on my charity.

The character of justice is easiest to see in the fundamental type of justice, commutative justice. 4 This is the justice of exchange and contract, the justice which specifies exact repayment of what is due. It is often called strict justice. But it is not the only sort. It is best contrasted with distributive justice. Under the latter, an authority, usually the state authority, is obliged to give benefits and exact obligations, not according to mathematical exactness, but according to a general understanding of the merits and needs of those subject to that authority in some way. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2411) expresses it: “Commutative justice obliges strictly; it requires safeguarding property rights, paying debts, and fulfilling obligations freely contracted…. One distinguishes commutative justice…from distributive justice which regulates what the community owes its citizens in proportion to their contributions and needs.” Although distributive justice is concerned principally with the state or civil society as a whole, nevertheless a homely illustration may help in our understanding. A mother borrows $20 from a neighbor to go to the bakery. She is obliged in commutative justice to repay exactly $20 to that neighbor. But, let us say, she decides to buy treats for her children at the bakery. Is she obliged to give each exactly the same kind and amount of treat? May she not take into account the fact that one child did an extra household chore, unasked, that another is struggling with a weight problem, that a third has an allergy to a favorite kind of pastry? Of course she may do so, and this shows the nature of distributive justice. It takes into account the manifold differences that exist within any group subject to the same authority.

But there is yet another kind of justice, legal justice. Legal justice concerns the obligations each person owes to the common good, as the Catechism further says: “what the citizen owes in fairness to the community….” And, indeed, it is legal justice that brings us to social justice, for essentially they are the same thing, or rather, social justice is a part of legal justice, or it is legal justice under a different aspect which emphasizes different facets of the virtue. The traditional conception of legal justice is that it is “a relation of the members to the community. It requires each man to contribute his proper share toward the common good… It is probably called legal justice because it shows itself chiefly in law-abiding conduct, but it goes beyond the bare requirement of the written law.” 5 Typical examples often given of acts of legal justice by moralists were paying taxes and obeying just laws. But social justice, while likewise concerned with the “relation of the members to the community” and the contribution of each one’s “proper share toward the common good,” strikes a slightly different note.

Pope Pius XI says of social justice, “Now it is of the very essence of social justice to demand from each individual all that is necessary for the common good” (Divini Redemptoris, no. 51). This sounds very like legal justice. Social justice, however, while likewise concerned with the duties of the individual to the common good, concerns not individual actions, such as paying taxes, but the fostering and establishment of organizations and institutions of society which contribute toward the common good. This exact note of social justice is best illustrated, I think, by a contrast which Pius XI drew in Quadragesimo Anno. The pontiff wrote: “Every effort must, therefore, be made that fathers of families receive a sufficient wage adequate to meet ordinary domestic needs. If in the present state of society this is not always feasible, social justice demands that reforms be introduced without delay which will guarantee every adult workingman just such a wage” (no. 71). Now, in order to understand the meaning of this passage, we must realize that a worker is due a living wage, a “wage adequate to meet ordinary domestic needs,” not in social justice, but in commutative or strict justice. Pius XI makes this abundantly clear elsewhere, for example, in Divini Redemptoris, his encyclical on communism, where he speaks of “the salary to which {the workingman} has a strict title in justice” (no. 49). 6 But if this is the case, then what role is envisaged for social justice in this passage? If we look carefully at the text, we will see that social justice is concerned, not with the individual rights of the laborer to a just wage or with the employer’s duty to pay such a wage, but with the organizations and institutions of society which allow such a wage to be paid. “If in the present state of society this is not always feasible, social justice demands that reforms be introduced without delay which will guarantee every adult workingman just such a wage.” In other words, social justice places demands on those responsible to make social or institutional changes. This is why it is a part of legal justice, for it concerns “what the citizen owes in fairness to the community.” And, in this case, upon whom is this duty incumbent? Again, Pius XI:

It happens all too frequently, however, under the salary system, that individual employers are helpless to ensure justice unless, with a view to its practice, they organize institutions the object of which is to prevent competition incompatible with fair treatment for the workers. Where this is true, it is the duty of contractors and employers to support and promote such necessary organizations as normal instruments enabling them to fulfill their obligations of justice (Divini Redemptoris, no. 53).

Although, in the next paragraph he makes clear that he is speaking of “a body of professional and inter-professional organizations,” sometimes termed “industry councils” or “occupational groups,” an organized system of industrial self-government akin to that of the medieval guilds. 7 The key point to note here is the distinction between what is demanded by commutative justice (payment of a living wage), and what is demanded by social justice (establishment of necessary institutions). Sometimes it is not possible to fulfill what is normally demanded by commutative justice because of lack of means. If I owe $1000 to someone but have just lost all my money because of an unexpected bankruptcy, then I cannot comply with what would ordinarily be a demand of strict justice. Similarly, an employer, although bound in strict justice to pay a living wage, is often handicapped by “an unjust economic regime whose ruinous influence has been felt through many generations,” as Pius XI put it, in which his competitors pay substandard wages. As part of this unjust system, he cannot always fulfill his duties because it would mean that he would be put out of business promptly. But, he is not thereby excused from doing something. For “it is the duty of contractors and employers to support and promote such necessary organizations as normal instruments enabling them to fulfill their obligations of justice.” Most often this duty would need to be fulfilled by joint action to establish the “necessary organizations” which fulfill the requirements of social justice, since a single individual employer by himself is often “helpless to ensure justice.”

However, this is not to say that such efforts are simply to be private efforts:

To that end (i.e., that social justice and social charity regulate the economic order), all the institutions of public and social life must be imbued with the spirit of justice, and this justice must, above all, be truly operative. It must build up a juridical and social order able to pervade all economic activity. (Quadragesimo Anno, no. 88)

In other words, there is a role for state action in helping to establish, and especially in securing and protecting, the institutions and organizations of social justice, by enacting, for example, legal safeguards for their proper functioning and, when necessary, enforcing their decrees by civil law. Even earlier, in Casti Connubii (no. 117), Pius had taught the same thing, “that in the State such economic and social methods should be adopted as will enable every head of a family to earn as much as, according to his station in life, is necessary for himself, his wife and for the rearing of his children….” 8 Thus, in addition to what they can do by their own efforts, such groups of employers would usually need to work for legal changes as well, and would properly coordinate their own activity with that of other interested parties, such as organized labor. 9

The most important thing to learn from Pius XI’s exposition of social justice is that it concerns reforming or establishing the institutions of society so that it becomes possible, or easier, for the individual members of society to fulfill their duties of justice and charity to one another. For this task, group action is necessary. Pius XI’s discussion of social justice concerned primarily its application to the economic realm, but in truth the basic principles he explains could be employed in other areas of social life. Our duties in this regard will be suggested by our position in society. If one is an employer, normally one of his primary duties will be to work toward a just economic order, for by participating in the economy as an employer, he has taken upon himself a grave responsibility for paying just wages. If he literally cannot do so in present circumstances, we have seen that he has a duty to work toward a different kind of economic order, not just to shrug his shoulders and say he is doing the best he can, or worse, to justify his conduct by an appeal to economic ideas that are not in accord with authoritative Catholic teaching.

The Church’s exposition of social justice reached a high degree of clarity in the writings of Pius XI. But nothing since then suggests that the mind of the Church has altered, or that Pope Pius’s teaching applied only to his own time. As Pope Benedict XVI, in his own social encyclical, Caritas in Veritate (no. 12), reminded us: “It is not a case of two typologies of social doctrine, one pre-conciliar and one post-conciliar, differing from one another: on the contrary, there is a single teaching consistent and, at the same time, ever new.”

The basic principles of social doctrine do not change, even if the external circumstances to which they must be applied can, of course, change. But it never comes about that a fundamental teaching of one pope is, or can be, overturned by his successor. Thus Pius XI appropriately characterizes the Church’s teaching in this area as “unchanging and unchangeable” (Quadragesimo Anno, no. 19).

Today, Catholics have largely forgotten the pre-conciliar teachings of the supreme pontiffs on social justice and the economy—especially Leo XIII, Pius XI and Pius XII. This is unfortunate, being yet another example of the loss of the Catholic historical memory since the Council. But the papal documents, and their teaching, remain as part of our heritage, awaiting only their discovery and appropriation by today’s generation of Catholics, eager to be faithful to the Magisterium. As such, Catholics applying themselves to recover what has been forgotten or neglected, will eventually encounter the Church’s social doctrine in its fullness. When this happens, they will find a path and a program set forth for the transformation of society. The formal title of Quagragesimo Anno is nothing less than “On Reconstructing the Social Order and Perfecting It Conformably to the Precepts of the Gospel.” Such a mission and such a task is worthy of the most valiant Catholics of this generation. and of every generation of the Church, until the return of our Lord. 10

- Summa Theologiae II-II q. 58, a. 1. ↩

- The Four Cardinal Virtues (Notre Dame, 1965) p. 72. ↩

- Austin Fagothey, Right and Reason: Ethics in Theory and Practice (Santa Clara : University of Santa Clara, 1953) p. 323. ↩

- The primary sources for the traditional understanding of justice are book V of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and question 58 and subsequent questions of the Secunda Secundae of St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae. ↩

- Austin Fagothey, Right and Reason, pp. 236-37. ↩

- Cf. Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, no. 34; Pius XI, Casti Connubii, no. 117, Quadragesimo Anno, nos. 71, 110; John XXIII, Mater et Magistra, no. 71; John Paul II, Centesimus Annus, no. 8. ↩

- Cf. Divini Redemptoris, nos. 32, 37 and 68 and Quadragesimo Anno, nos. 81-87. ↩

- See also Divini Redemptoris, no. 75. In Quadragesimo Anno (nos. 76-80), in treating of the principle of subsidiarity, Pius explains more fully the specific tasks of the state and of the occupational groups and other lower bodies. For a later discussion of these points, see John XXIII, Mater et Magistra, nos. 61-67. ↩

- Cf. Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, no. 36. ↩

- Fr. William J. Ferree’s booklet, Introduction to Social Justice, orginally published in 1948 by Paulist Press, is a good delineation of the nature and role of social justice. It is available today from the Center for Economic and Social Justice. However, the preface to the CESJ edition differs in many respects in its point of view from Fr. Ferree’s own work and thus should not be looked upon as an accurate exposition of the Church’s doctrine. ↩

Catholics know little about any of the Catholic Social Doctrine. I have asked Catholics in many settings: What is the meaning of the principle of universal destination of goods? I have yet to get a good answer. We have along way to go before we can begin to understand different ideas of justice. Keep working on helping to build understanding. Those most in need around the world desperately need Catholics to practice Catholic Social Doctrine. Zhao Ji Yong, Chinese reformer who spent years under house arrest for opposing the use of violence in Tiananman Square in 1989, said that Catholic social teaching would be good for China. How can Catholics effectively propose teaching they do not practice themselves?

This article has been posted on Free Republic, and has elicited a number of comments. One of the commentors accused me of using “translation of encyclicals which differ from those at the Vatican’s web site.” I am replying here for the record. It’s true, I usually use the translations of the older encyclicals published by Paulist Press in Seven Great Encyclicals (out of print), which is an older translation sometimes differing a bit from the English translation on the Vatican website. Most of the time the difference is unimportant. But this commentor notes one point where he thinks I have distored the meaning of the encyclical. This is in Divini Redemptoris #51, where I quoted, “Now it is of the very essence of social justice to demand from each individual all that is necessary for the common good.”

This commentor wrote, “The Vatican translation is: Now it is of the very essence of social justice to demand for each individual all that is necessary for the common good. This small error twists the statement to its opposite meaning.”

It is true that the Vatican translation does have “for” instead of “from.” But I think this is an error in the Vatican’s translation. Here is the Latin of that sentence, taken from the Vatican website.

“Atqui socialis iustitiae est id omne ab singulis exigere, quod ad commune bonum necessarium sit.”

Anyone who knows Latin will see that “ab singulis” means “from each one,” not “for each one.” Therefore I maintain that the translation I used was correct.

I am replying here because I am not registered on Free Republic and do not wish to register there.

Yes most Caholics not academically educated will not have the smallest knowledge of Social Justice or of Pius xi. Studying these items is only found in a deparment of a university.