If the sacrament of marriage came to be specified at a particular moment, then as the renewal of marriage was itself an indication of a new beginning … it makes sense that the marriage of Mary and Joseph was precisely the implicitly liturgical moment of a new beginning.

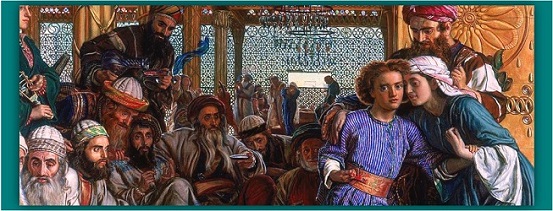

Finding of the child, Jesus, in the Temple.

The Christian sacrament of marriage is both “consonant” with that of Judaism and, at the same time, a renewal and development of it. 1 For it seems clear that if the Eucharist “grew out” of the Passover, other sacraments of the Christian Church have “emerged” out of a similarly significant Old Testament background. Thus, the Catholic understanding of the integral nature of Scripture, Tradition, and the Magisterium (cf. Dei Verbum, 7-10; Catechism of the Catholic Church {hereafter, CCC} §75-83) is actually a kind of continuation of the ancient biblical culture of Israel, which was “word,” “liturgical and cultural practices,” and charismatic leadership. In other words, in the cultural context of the coming of Christ, there emerges a sense of an “opportune moment,” a favorable time, in which Judaism as a whole, and the Jewish rite of marriage in particular, was “ripe” for transformation through the coming of Christ. With the coming of Christ there is a somewhat seamless passing of the Old Testament rite of marriage, but now bearing a new reality, into the apostolic age of the early Church. As with the promulgation of the Dogma of the Assumption of Mary, liturgical evidence is a part of the general evidence of the inseparable relationship between Scripture and Tradition; 2 and, therefore, the way that we are introduced to the new nature of marriage has a kind of discreetness which “fits” in with the logic of the incarnation. 3 If the sacrament of marriage came to be specified at a particular moment, then as the renewal of marriage was itself an indication of a new beginning, “echoing” the beginning, 4 it makes sense that the marriage of Mary and Joseph was precisely the implicitly liturgical moment of a new beginning.

Finally, it is hoped that these reflections will contribute to the sense that if the sacraments are taking up, as it were, a prior Jewish form, the very historical process reveals a sensitivity to the very “passage” of the transformation of Judaism into Christianity. In other words, marriage stands at the “beginning” of this transformation, taking up as it does the marriage of Joseph and Mary in the context of the coming of Christ, whereas the institution of the Eucharist requires a more explicit beginning. Scripture reflects a kind of implicit movement, from within, from the Old to the New Covenant: a transition which passes through the natural states of life and suggests a “passage” which is entirely sympathetic to the very states and stages of life so characteristic of our humanity. It may actually be completely relevant to understanding “how” God acts, that the sacrament of marriage is instituted discreetly and recognized as a distinct reality only as the light of Christ’s relationship to his Church is understood as the “marriage of the Lamb” (Rev 19:7; cf. also Eph 5:31-33). 5

In the context of a very brief overview of the Bible as a whole, there are seven “moments” to consider: (1) the Book of Tobit; (2) Christ and the covenant; (3) the marriage of Mary and Joseph; (4) Christ and his vocation to celibacy; (5) Cornelius and his family; (6) St. Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians; and (7) the early Patristic period.

Background

In general, the Scripture opens and closes with both the marriage of Adam and Eve, to which Christ refers (cf. Mt 19:4-6) and the marriage of the Lamb in the Book of Revelation. Thus, the marriage of Adam and Eve constitutes a first and foundational expression of the mystery of marriage; indeed, given the existence of Adam and Eve prior to the Fall through original sin, the union of Adam and Eve fell within the mystery of “original justice” (CCC §376). 6 Furthermore, the language of the covenant, applied explicitly after the fall to the promises God made to his people (cf. Mal 2:10), is also applied to marriage (cf. Mal 2:14). Not only is there a development in “interiority” to the explicit covenants themselves, such as between the covenant with Noah and the sign of the rainbow to the covenant with Abraham in the sign of circumcision, but there is also a kind of cross-fertilization between covenant as a relationship between God and his people as a whole, and the marriage of a man and his wife. It becomes increasingly significant that in a Jewish marriage, the covenant between God and his people at Sinai is deliberately recalled, and constitutes a central feature of the marriage ceremony. 7 Consequently, it is necessary to trace some of the interconnected elements that contribute to grasping the growing significance of the relationship between the Jewish rite of marriage and the “institution” of the sacrament of marriage. We are now going to look in a little more detail at a Book which is almost an exposition of marriage in the context of the transmission of faith and family life.

The Book of Tobit: Second through Seventh Century B.C.

The Book of Tobit 8 is one of the deuterocanonical books, one of the books disputed as to whether or not it was Scripture: “Rabbinic Judaism and founders of Protestantism rejected the deuterocanonical books; some Protestant Bibles print them in a separate section called Apocrypha.” 9 One wonders what determined this rejection of the Book of Tobit; and, as such, one answer was that its authorship was so late, reputedly A.D. 100, although new evidence dates it significantly earlier. 10 Another reason for its rejection was that it expressly contravened a rabbinic practice: “Other scholars have postulated that Tobit was excluded from the Jewish Scriptures for a halakhic 11 reason, because the marriage document discussed in Tb 7:16 was written by Raguel, the bride’s father, rather than by the groom, as required under Jewish rabbinical law.” 12 While it is not possible to discuss this further, it is clearly significant that the Book of Tobit is a controversial text and, as such, stands so clearly in the development of our understanding of marriage. It has also been noted that in this book, there is mention for the “first time … in the Bible (of) a formal marriage contract involving a written document”; 13 however, it is mentioned in such a way as to make one think that this was a usual practice and was, “in time … (to) be called by Jews the Ketubah.” 14

The Book of Tobit

In general, the Book of Tobit depicts marriage at two stages: a marriage and its difficulties towards the end of life (Tobit and his wife Anna); and, at the same time, considers the difficulties that beset the possibility of marriage (Tobias, the son of Tobit and Anna, and Sarah, the daughter of Raguel and Edna). There is an angel, Raphael, who both leads Tobias to Raguel, and to marriage with his daughter Sarah; and at the same time as the angel instructs Tobias on how to defend Sarah from a demon (Tb 6:7), Raphael also instructs Tobias on how to cure his father’s blindness (Tb 6:8).

Although there is a sense in which Tobias is marrying one to whom he is, as it were, intended by kinship (Tb 4:13; 6:9-17), Sarah’s marriage to Tobias is, nevertheless, in answer to her own prayer for deliverance from this demon, and her own unhappiness (cf. Tb 3:10-17). Furthermore, lest we think in terms of the Sarah’s readiness to marry someone she does not know except in terms of how he has presented himself to her father and the family Tobias comes from, we can already see that Tobias fell in love with Sarah even before he met her; for, following the angel’s description of her, and of how to help her, and to conduct himself, it says of Tobias that “he fell in love with her and yearned for her deeply” (Tb 6:17). The key question, then, is not so much the modern and contentious question of “individual freedom,” 15 but, rather, Tobias and Sarah’s participation in a dialogue with God and, therefore, with a perception of their own happiness in the context of the “providential” action of God at work in their own lives.

On arriving at Ecbatana, the home of Sarah and her family, Tobias declares to Raphael his desire to marry Sarah. Raguel, Sarah’s father, overhears, and at Tobias’ insistence, makes a “gift” of his daughter Sarah to Tobias. Taking Sarah by the hand, Raguel gives her to Tobias, saying, “take her to be your wife in accordance with the law and the decree written in the book of Moses” (Tb 7:13; and 7:1-15). Immediately afterwards, Raguel asks his wife Anna “to bring writing material; and he wrote out a copy of the marriage contract, to the effect that he gave her to him as wife according to the law of Moses” (Tb 7:14).

Finally, Tobias follows the instructions of Raphael, and drives the demon away from Sarah. Tobias and Sarah pray together, and go to sleep. Beginning the following day, there was a two-week celebration of the marriage, twice as long as usual, 16 and a gift of half of Raguel’s family wealth to Tobias (cf. Tb 8). In passing, we can note, too, that the prayer that Tobias makes refers to the beginning in these words: “You made Adam and gave him Eve, his wife, as a helper and support. From them the race of mankind has sprung” (Tb 8:6). Thus, if we consider all the elements of the religious life which are lived (almsgiving, prayer, trust in providence, and so on), and which, therefore, support marriage, we can see what a comprehensive catechesis on the integrity of the life of faith is embodied in the Book of Tobit.

The Covenant of God and Israel: Christ and the Covenant

Given that the key relationship for Israel, of the covenant of Sinai, is a kind of marriage between Israel and God, brings a new significance to the marriage feast of Cana (cf. Jn 2:1-11) 17 to find that Christ is present at what is, according to traditional Judaism, a “moment” of remembrance of God “wedding … Israel.” 18 Indeed, Christ himself, in referring to the gift of the Eucharist, takes up precisely this language of the covenant, particularly at the Institution of the Eucharist when he refers to the cup, “saying, ‘This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood …’” (Lk 22:20). Thus, the Church says of Christ’s presence at Cana that it is both the “confirmation of the goodness of marriage, and the proclamation that, henceforth, marriage will be an efficacious sign of Christ’s presence” (CCC §1613). “This grace of Christian marriage is a fruit of Christ’s cross, the source of all Christian life” (CCC §1615). This indicates a kind of perspective of the cross, as the perspective in which the sacrament of marriage exists: the cross through which the water of suffering is changed into the wine of rejoicing and thanksgiving (cf. Jn 2:3-10).

The Gospel of St. Matthew

This Gospel is traditionally ascribed to the apostle Matthew 19 because it was thought to be “written for Jewish Christians” as it “stresses that Christ is the fulfillment of the Old Testament Scriptures,” and “Jewish customs are mentioned without explanation.” 20 In this particularly Jewish Gospel, a Gospel which comes first in the New Testament canon and, as such, is almost an indication of the Jewish roots of Christian life, we find a number of references to marriage. In the details of the parables, such as the virgins carrying lamps (cf. Mt 25:1-12), 21 in reference to wedding garments (cf. Mt 22:12), 22 and a feast (cf. Mt 22:2-3; 25:10), 23 the general impression is that the parables are drawn from familiar, contemporary experience and, in this case, draw upon a profoundly lived liturgical reality of marriage. In a primary sense, however, it is clear that Christ’s reference to the “beginning” is a key to his understanding marriage as both an “original” gift of God, and a decisive act of God: “What, therefore, God has joined together, let no man put asunder” (Mt 19:6). When it comes, then, in due course, to understanding the relationship between the covenant and the sacrament of marriage, it is clearly relevant that there is a “parallel” act of God in bringing about both the covenant and marriage.

The Cultural Context of the Marriage of Mary and Joseph

When it comes to the marriage of Mary and Joseph, there is no mention of the custom of arranged marriages, nor of the details that surround the marriage of Mary and Joseph; however, as with the marriage of Tobias and Sarah, it seems possible to consider these things in the context of prayer, and the answering action of God, in which, in general, the devout understood their lives to be lived in the context of divine providence. There is an indirect mention, as we shall see, of a distinction between a legally binding act of betrothal, called qiddushin (pronounced: kiddushin) and, in due course, the married couple coming to live together. 24 A question that arises, then, is this: was this distinction between a binding betrothal and cohabitation a relatively unique feature of Jewish marriage in the “ancient Near East”? 25 What, then, prompted its development? Could the answer be that it was a “ritual” development of the growing understanding, within Judaism itself, of the significance for marriage of the covenant at Sinai? For example, it is the prophet Malachi who uses the language of the covenant for both marriage, and the relationship of God to Israel; and if Malachi was written in about “the fifth century B.C.,” 26 then, it puts this development almost between the Book of Tobit and the New Testament.

While there is no explicit use of the word “covenant” in the Book of Tobit, it is interesting to note that Sarah’s father, Raguel, when drawing up the “marriage contract” (Tb 7:14), “wrote out a copy of the marriage contract, to the effect that he gave her (Sarah) to him (Tobias) as wife according to the law of Moses” (Tb 7:14). While there is no explicit use of the word “covenant,” it seems there is clearly an understanding that marriage is specified by the law of Moses and, as such, by the context of the covenant between God and Israel, which that law expresses. In addition, there is the whole emphasis, as it were, in the Book of Tobit as a whole, on the two tables of the law: the love of God, and the love of neighbor, with particular reference to the “fourth commandment (that) opens the second table of the Decalogue.” 27 In other words, although it is not the case with the marriage of Tobias and Sarah, was there a subsequent development of the parallel between the giving of the Law at Sinai, and the people dwelling with God in the desert, and the distinction in the rite of marriage between the formal betrothal, and the later coming together? Was it a kind of ritual expression of the relationship between the marriage of a man and a woman, and the marriage of God and his people? 28

Pope John Paul II and “Redemptoris Custos”

In St. John Paul II’s Apostolic Exhortation on St. Joseph, Redemptoris Custos (hereafter, RC), we see how the pope reflects on Scripture, and draws on a tradition of the distinction between marriage and cohabitation, both contemporary to, and indicated in, the marriage of Joseph and Mary in St. Matthew’s Gospel (cf. Mt 1:18-21; RC §18). 29 Furthermore, Pope John Paul II uses the insights of Pope Paul VI, who said:

In this great undertaking which is the renewal of all things in Christ, marriage—it too purified and renewed—becomes a new reality, a sacrament of the New Covenant (emphasis added). We see that at the beginning of the New Testament, as at the beginning of the Old, there is a married couple. But whereas Adam and Eve were the source of evil, which was unleashed on the world, Joseph and Mary are the summit from which holiness spreads all over the earth. The Savior began the work of salvation by this virginal and holy union, wherein is manifested his all-powerful will to purify and sanctify the family—that sanctuary of love and cradle of life (RC §7). 30

Although one possible beginning to the sacrament of marriage is Christ’s presence at the marriage feast of Cana, 31 in the very complex mystery of the Holy Family, we have grounds for understanding that the marriage of Mary and Joseph was in fact the first marriage: “a sacrament of the New Covenant” (RC §7). First, through the mysteries present in this unique event, Mary, who was conceived without sin (Lk 1:28), has already received, as it were, the “baptism” of the Immaculate Conception. Second, on believing the message of the angel that she was to conceive “Jesus” (Lk 1:31) and become the mother of the “Son of the Most High” (Lk 1:32), she has professed her faith in Christ. When Joseph, her husband, believed the message of the angel, that the child Mary has conceived is “of the Holy Spirit” … and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins” (Mt 1:20-21), then, it is clear that Joseph has undergone a “conversion.” Joseph, having married Mary and found that she is pregnant not by him, turns from sending her away, and instead takes her to his home. Thus, Joseph has also implicitly professed his faith in Jesus; and, although there is no mention in Joseph’s case of any kind of “baptism,” yet, it is possible that, in Joseph’s conversion to Christ, there is an action of God equivalent to baptism: “Since it is inconceivable that such a sublime task would not be matched by the necessary qualities to adequately fulfill it, we must recognize that Joseph showed Jesus by a special gift from heaven, all the natural love, all the affectionate solicitude that a father’s heart can know” (RC §8). 32 Both Mary and Joseph seem to be replete with all the ingredients of what constitutes Christian marriage; and, what is more, in so doing, their lives seem to reflect an implicit participation in all the graces that are a part of it, explicitly so in the case of Mary’s Immaculate Conception being a “baptism.”

Furthermore, then, in that their child is Jesus Christ, true man and true God, and the new high priest (cf. Heb 4:14-5:10; and 6:11–10:18), 33 it is as if we can say that the Holy Family is replete with all the sacraments of the Church, either explicitly or implicitly. On the one hand, perhaps we do not disclose anything by the claim that the whole sacramental order was “inchoately” present in the Holy Family, precisely because it was not explicit. On the other hand, if existence comes before thought, there is a sense in which the actual reality of the Holy Family may have a certain priority and “governing” influence over the development of doctrine: “it is in the Holy Family, the original Church in miniature (Ecclesia domestica), that every Christian family must be reflected” (RC §7).

Thus, it is not so much that there needs to be a discrete institution of the actual sacraments, as the actual sacraments are an unfolding of the implicit logic of the incarnation as it unfolded in the life of Mary, Joseph, and Jesus. Having said that there does not need to be a discrete institution of the sacraments one can see, nevertheless, that there are “moments” when what is “implicit” in the mystery of salvation is made “explicit.” To that extent, there is both an unfolding of the logic of the graces given to Mary and Joseph through the coming of Christ, and there are particular moments when the sacramental mystery, entailed in the very nature of the Holy Family’s existence in Christ, is made manifest. A clear example of the latter is, of course, the Institution of the Eucharist (cf. Mt 26:26-29). Here is the very mystery of God made man, as well as the taking up “from within” the tradition of the Passover, and the offering of the paschal lamb (cf. Jn 1:29, 36), and the translation, as it were, of the self-offering of Christ into the gift of the “bread of life” (Jn 6:35).

The Interrelationship of Christ’s “Chosen Celibacy” and the Vocation to Marriage

A further question that arises, then, is precisely the emergence of the understanding of Christ’s love of the Church as a development which assisted in the articulation of the sacrament of marriage. 34 In general, it appears that just as the ecclesiology of the Church as a whole was the natural context for the Second Vatican Council referring to the domestic Church (Lumen Gentium §11), so our understanding of the sacrament of marriage is “founded” on a clear perception of Christ’s love of the Church. There is both the supposition of the complete and integral nature of the gift of grace to the Holy Family of Nazareth: Jesus, Mary and Joseph; and also the canonical structure of the New Testament, beginning with the Gospel of St. Matthew, and ending with the Book of Revelation. Consequently, it is almost as if the passage of the New Testament is from a consciousness of the Jewish inheritance, as epitomized in the Gospel of St. Matthew, and never, in a sense superseded, to a complementary grasp of the spiritual realities unfolded in the New Testament and in the Scripture as a whole. The Gospel of St. John, opening with the meditation on the Word, Logos, which “became flesh” (Jn 1:14), comes as the last of the Gospels, fittingly bridging the transition to uniquely spiritual understanding, culminating in the Book of Revelation, of Christ as the bridegroom of the Church.

Not only are there many references in the Gospels to marriage, but John the Baptist applies this imagery to Christ himself: “the friend of the bridegroom, who stands and hears him, rejoices greatly at the bridegroom’s voice” (Jn 3:29). 35 Furthermore, there is a sense in which these references are “understood” to refer both to a great wedding feast (Mt 22:1-14), implying the many who are coming, as well as to Christ, who applies the image of the bridegroom to himself: “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who gave a marriage feast for his son …” (Mt 22:2). As a whole, then, not only does the New Testament go from the event of marriage (in particular the marriage of Mary and Joseph) to the spiritual significance of that marriage event, but also Scripture as a whole goes from the marriage of Adam and Eve to the marriage of the Lamb. 36

There is, thus, an emergence of Christ’s vocation to celibacy 37 in the context of the Holy Family of Nazareth. Here, all things seem to be inchoately present in terms of the “reality-sign” of the interrelationship between marriage, the vocation to virginity, and the unfolding of family life. There is the vocational celibacy of Mary and Joseph in the context of their marriage, which, in its own way, gives grounds for the vocational celibacy of Christ being understood in the light of marriage: the spiritual marriage between God and his people being embodied in the vocational celibacy of both Mary and Joseph. Moreover, in the light of what Pope John Paul II says in Familiaris Consortio (hereafter, FC), the interrelationship of love and fecundity in the Holy Family of Nazareth seems to give rise to a particularly extraordinary image of the interrelationship between the Holy Family and the communion of the Blessed Trinity: “God is love and in himself he lives a mystery of personal loving communion. Creating the human race in his own image and continually keeping it in being, God inscribed in the humanity of man and woman the vocation, and thus the capacity and responsibility, of love and communion. Love is therefore the fundamental and innate vocation of every human being” (FC §11). 38

While, then, there are other factors in the dialogue between the vocations to marriage and celibacy, and the articulation of their respective differences and similarities, the unique nature of the Jewish marriage and family life of Mary, Joseph, and Jesus, is clearly a contributory factor in the inner logic of Christ understanding his relationship to the people of God in the light of God’s covenantal love of his people.

The Word of God: Christ and the Vocation to Celibacy

Drawing on a background of ideas and practices 39 that may not so much reflect the exact times of the Holy Family, we can still see that there are trends in thinking which were probably older and, as such, could have a bearing on how to understand a key relationship in the life of Christ—namely, that between the “lived Scriptures” of his daily life and worship, and the mystery of his own identity.

There is the very mystery of the Logos: the “Word became flesh” (Jn 1:14); and, therefore, the mystery of the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity being manifest in the person and activity 40 of Jesus Christ. Additionally, Jesus was subject to his supposed father, Joseph: “feeding, clothing and educating him in the Law and in a trade, in keeping with the duties of a father” (RC§16). 41 Moreover, “marriage … establishes the family as the basic social unit and the home as ‘the little sanctuary’ (Ez 11: 16) in which the father is like a priest, the mother like a priestess, and the dining-room table like an altar (Berachot 55a), where children can enjoy their childhood, and grow to maturity under the loving protection and guidance of their parents, and where the Jewish religion can be practiced, experienced, and transmitted from generation to generation.” 42 And so, with respect to bringing up Jesus, Joseph fulfills the injunction of the Shema: 43 “and you shall teach them diligently to your children” (Dt 6:7); and what Joseph shall teach his child Jesus is that “The Lord our God is one LORD; and you shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” (Dt 6:4-5). It is not clear whether Jesus had observed the bar mitzvah, the rite that establishes a Jewish boy of 13 as responsible for fulfilling the law himself, or not. 44 In the answer that Jesus gave to his parents when he was 12, however, 45 Jesus shows that he has identified his mission with that of his Father’s house and, in a sense, expressed a wholehearted love of God and dedication to his will: “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” (Lk 2:49). As such, Joseph has accomplished his mission as a father in assisting Jesus to understand the history of salvation as the Shema commands; and, in a certain way, the boy Jesus, through his public expression of who he is to his parents, has fulfilled the bar mitzvah, and is now able “to perform certain parts of religious services, to form binding contracts, to testify before religious courts, and to marry.” 46

Christ’s Transformation of What He Received

Clearly, though, the sense in which Jesus himself understands his mission is both in terms of his unique identity as the Son of God, and as one who is taking up the inheritance of being taught that they were delivered from slavery as the “Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand” (Dt 6:21). The visits that his family made to the Temple in Jerusalem and, indeed, their whole work of transmitting the history of salvation to Jesus, are a part of that human assimilation of his religious inheritance that, in due course, would inform the life and, indeed, the liturgical action of Christ. In other words, there was a long process by which Christ assimilated what he was then to transform—in particular—the Passover (cf. Lk 2:41-42); for, to borrow and adapt an expression from Pope Emeritus Benedict (then, Cardinal Ratzinger), Jesus “universalizes” redemption from slavery to redemption from sin. It is perhaps significant, too, that while the early tradition of the Eucharist retained the meal as distinct from the “breaking of the bread,” in time, the Church discerned the “essential” ingredient of the liturgical Eucharist 47 (cf. 1 Cor 11:23-26) and encouraged people to eat at home (cf. 1 Cor 11:33). In other words, in the very way that Christ passed the “Passover” on to the Church in the Last Supper as the first Eucharist, he disclosed a sensitivity to “accepting” the Passover as he received it (cf. Mk 14:12-21), and only then, like a husk being shed from a seed, did the meal (cf. Mk 14:22) become separated from the Eucharist.

Furthermore, as this is the last time that the Gospel mentions Joseph, except in passing (cf. e.g. Lk 3:23), 48 this identification of the Fatherhood of God by Jesus himself becomes very significant; it is as if Jesus had begun a process of differentiation which, in due course, would identify who he is, increasingly confound his own family (cf. Mt 12:46-50; Jn 7:1-9), and establish the relationships constitutive of the Church. In other words, while Jesus Christ is going to bring an incredible dynamism to his public ministry and turn, as much “outwards” as the childhood years were “inward” and undisclosed, he is also going to transform his relationship to his mother, and ultimately, to all of us, such that we all share the “outreach” of God to us. Again, Jesus will take up a characteristically Jewish and Greek relationship of teacher to disciples 49 and, at the same time, unite it with a new understanding of his family as “re-founded” from the Father: “For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother, and sister, and mother” (Mt 12:50).

There is, then, a definite sense of Jesus fulfilling his human sonship in the remaining years in the family before his public ministry; and, as such, living out to the full in the family as a place of formation, as a place of dwelling with the word, in Hebrew a yeshiva (meaning to dwell with the word): 50 an expression almost more applicable to his family than to Jesus himself. Nevertheless, given Jesus’ own period in the desert (cf. Mt 4:1-11), whereby he fulfilled Israel’s dependence on providence (cf. Nm 32:13), we see that Jesus says of the word: “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God” (Mt 4:4). The inner being of the Word made flesh is completely fulfilled in his dependence on “every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.” Ultimately, Jesus resolves the question of his vocation in terms of a complete and perfect fulfillment of the Shema. When, therefore, Jesus is asked about the greatest commandment of the law, he is able to say: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Mt 22:36-37). Going on to give the second commandment, he spoke of the love of “neighbor as yourself” (Mt 22:39). In the end, however, all this is expressed perfectly on the cross: both obedience to God and love of us: “as God formed the woman from the side of Adam, so also Christ has given us the water and the blood from his side in order to form the Church. … his Bride.” 51

Cornelius, the Roman Centurion, in the Acts of the Apostles

We must also note, albeit in passing, that whole families became Christian while at the same time, having only gentile roots. For example, in the Acts of the Apostles, there is the notable case of Cornelius, a centurion, and his family, who converted directly to Christianity (cf. Acts 10). However, although this circumstance occurs early on in the spread of Christianity, it is not at all clear that it would be evidence of a different “influence” on the practice of marriage or the celebration of it.

Aside from the question of cultural influence, St. Paul draws a conclusion about a marriage between unbaptized persons: “a lawful and consummated marriage between unbaptized persons can be dissolved when one of them converts to Christianity, and the other opposes the faith, or desires to be separated from the newly baptized spouse” (cf. 1 Cor 7: 12-15). 52

St. Paul and the Letter to the Ephesians

In general, there are numerous aspects to the teaching of St. Paul 53 on marriage, and, as such, it can be implied in some general accounts that it was not regarded positively: “The New Testament has a negative attitude to the sexual impulse, and regards celibacy as a higher ideal than marriage (Mt 19:10; 1 Cor 7).” 54 But more precision is necessary as the New Testament teaching on marriage does involve a recognition of numerous aspects, particularly in the writings of St. Paul. 55 What emerges, however, given the Jewish emphasis on marriage and the traditions that developed and communicate its meaning, is that there were well established practices, liturgical rites, and celebrations, 56 which show us that Christian marriage emerged out of a real and rich tradition which, nevertheless, with the coming of Christ, was given a new beginning in what came to be understood as the sacrament of marriage.

What is particularly decisive in this “articulation” of the sacrament of marriage is the theology of St. Paul in the Letter to the Ephesians. By contrast, for example, in St. Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, although there is some similarity of content (cf. Col 3: 18-25), there is no mention of this new relationship between Christ and the Church and marriage (Eph 5:21-33). It is in the Letter to the Ephesians that St. Paul develops

… the theological theme found in the Old Testament of connecting marriage with the covenant between Israel and the Lord. In the New Testament, this theme is transformed into the image of the Church and Christ as bride and groom: “As the church is subject to Christ, so let wives also be subject in everything to their husbands. Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Eph 5: 24-25). Evoking the teaching of Genesis that the two shall become one flesh, Paul adds, “This mystery is a profound one, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church.” (Eph 5: 32; CCC §1616). 57

In other words, given the background of St. Paul in the teaching and practices of Judaism, it is completely coherent that it should be St. Paul who sees the new relationship between God and his people expressed in the uniqueness of the relationship of Christ to the Church; and, in view of the traditional understanding of Jewish marriage recalling the covenant between God and his people on Sinai, that St. Paul grasps the new expression of the relationship between Christ and his people as involving a new understanding of marriage. Just as significantly, however, Paul has grasped that Christ “stands” to the Church as “God” stood to the people of the covenant. Christ has become a “point” of intersection between God and the Covenant: the Church and the sacrament of marriage. Nevertheless, there is a kind of similarity between a sacramental understanding of the marriage and the Jewish perception that “When a man cohabits with his wife in holiness, the Shechinah is with them” (Kitvey Rabbenu Mosheh ben Nachman, Mosad ha-Rav Kook, Vol. II, p. 323). 58 In the end, Christ really does seem to bring both a new reality and realization of the “spiritual wealth” of the Jewish tradition from which Christianity springs. In what follows, we will note a few early testimonies to the reception of the sacrament of marriage.

Early Testimonies from Tradition to the Nature of Marriage

As we emerge from the apostolic tradition and begin to traverse the patristic tradition, the both of which are dynamically related in that the latter is constantly returning to the former as to its origin and original inspiration, we can discern more clearly the constancy of the sacramental tradition of marriage. It may be, for example, that this tradition shows itself in the very discrete way of signaling a difference in how marriage is lived by Christians and perceived by others; and, therefore, in the Letter to Diognetus, we read that Christians marry but do not share their marriage bed or expose their infants to death. 59

St. Ignatius of Antioch speaks more explicitly of the nature of Christian marriage in his “Letter to Polycarp,” (67 (5,1) when he says: “Speak to my sisters that they love the Lord, and be content with their husbands in body and in soul. In like manner, exhort my brothers in the name of Jesus Christ to love their wives as the Lord loved the Church (Eph. 5:25).” What is illuminating, too, is that St. Ignatius encourages those who want to marry to discern their motive: “It is proper for men and women who wish to marry to be united with the consent of the bishop, so that their marriage will be acceptable to the Lord, and not entered upon for the sake of lust.” 60 There are two particular reasons, if not three, for commenting on this reference to “the consent of the bishop.” In the first place, there is an almost implicit biblical reference to the Book of Tobit, 61 where Tobias prays to take his wife Sarah for the right motive: “And now, O Lord, I am not taking this sister of mine because of lust, but with sincerity” (Tb 8:7).

Additionally, the involvement of the bishop evinces a sense of the interrelationship between the mystery of the Church and the sacrament of marriage. Finally, there is an almost “institutional” expression of how, previously, a marriage arose through the mediation of fathers and other family relatives implicitly communicating the providential action of God, whereas now that discernment of the vocation to marriage is “ordered” to the life of the Church. Although, in a way, the testimony of the Council of Trent is well removed historically from this period, what emerges in the language of Trent is an incredible echo of the whole process of discernment and involvement of the Church and liturgical variety: “I join you together in marriage, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, or use other words according to the accepted rite of each province.” 62

St. John Chrysostom (347-407) teaches on marriage and says the family is a “Domestic Church” and presents a fullness of Christian family life, which, for most of us, remains a goal to be accomplished, and reveals how fully involved in the practice of the faith the whole family is intended to be. 63 The Second Vatican Council drew afresh on the doctrine of the “domestic church” when it wrote on the mystery of the Church as a whole (cf. Lumen Gentium §11). What is also very striking is that there is a similar expression and substance in Judaism, whereby it is said that “marriage … establishes … the ‘little sanctuary’” of the home. 64 In other words, even if the expression of the Christian Faith in the family was called a “Domestic Church,” there was a similar and almost identical expression in Judaism of the “Little Sanctuary”; and therefore, we can see that the Holy Family was both a “Little Sanctuary” and a “Domestic Church”: living out the fullness of Judaism and beginning again in Christ.

We conclude this brief review with Tertullian (c. 200) 65 who deserves a mention for his reflections on marriage, in the course of which he raises some questions about another aspect of the thought of St. Paul on the sacrament of marriage. For it is Tertullian who reflects on St. Paul’s words about those who “marry in the Lord” (cf. 1 Cor 7:39). 66 Clearly, however, there are numerous references in St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians which pertain to marriage and which need exploring, particularly the verses on vocation (1 Cor 7:7, 17) and what the Lord says about marriage “that the wife should not separate from her husband” (1 Cor 7:10); and also that St. Paul encourages a widow to marry “whom she wishes, only in the Lord” (1 Cor 7:39). The latter is taken by Tertullian to mean that the widow is to marry “a Christian,” 67 which clearly could include the sense of the sacrament of marriage as to marry another Christian is to enter the sacrament of marriage. For, subsequent to the passage quoted, Tertullian writes his famous praise of marriage, extolling “the happiness of that marriage which the Church cements,” 68 which again could be referring to the sacrament of marriage. Furthermore, Tertullian extols the whole mutual help of husband and wife, understood as a mutual help to lead the Christian life, which is taken to be such a “modern” understanding of marriage. Tertullian says, for example, “Together they pray, together prostrate themselves, together perform their fasts; mutually teaching, mutually exhorting, mutually sustaining. Equally (are they) both (found) in the Church of God; equally at the banquet of God; equally in straits, in persecutions, in refreshments.” 69

While the evidence for the passage of the Jewish rite of marriage “into” the Christian sacrament of marriage, beginning with the marriage of Mary and Joseph, would seem to be profoundly implicit in the life of the Church, it does seem to reveal a profound sensitivity to the very human nature of this development. In other words, the Incarnation of the Son of God entailed a kind of principle of incarnation in the very transformation of the Jewish cultural life into which he came, and through which he was to express the new life he came to give us. In the end, however, the Holy Family is both an incredible communication of the mystery of the Blessed Trinity (cf. Familiaris Consortio §11; Letter to Families §6), an amazing interpenetration of the human and divine reality, 70 and the human origin of the transition from a Jewish inheritance, to the Christian sacrament of marriage, and understanding of vocational celibacy. 71

While this essay began with the perception of the relevance of the Jewish rite of marriage to the Christian sacrament of marriage, what has been unexpectedly pivotal in the whole discussion is the “embodied” reality of this “moment” of transformation in the mystery of the Holy Family. Finally, while considering what seemed to be a tangent, namely the vocation of Christ to celibacy, it becomes clear that it was through the Holy Family that Christ encountered the formation that was to express his vocation as a fulfillment of the Shema: loving God and man to the end. In other words, the inner logic of the Incarnation shows itself, ultimately, in the Word “being from” the communion of the Blessed Trinity and that of the Holy Family, and constituting, with the Holy Spirit, the communion of the Church; and, therefore, the language of the celibate bridegroom is the ultimate spiritual expression to which marriage, from the beginning, has orientated the eschatological hope of salvation.

- This paper has arisen out of giving a number of lectures to a wide range of students on different courses at the Maryvale Institute and, at the same time, given the need for assistance at times of weariness, the need to formalize a kind of dialogue with a number of different sources. I am grateful to those who have contributed, directly or indirectly, to the opportunity to develop these ideas. ↩

- Cf. Pope Pius XII, Munificentissimus Deus, 12, 16 and especially 20, where it says: “since the liturgy of the Church does not engender the Catholic faith, but rather springs from it …” Thus making clear that the liturgy is not an alternative source of doctrine but, together with Scripture and Tradition as a whole, manifests the fullness of faith and thus can be drawn upon for our understanding of it. ↩

- Cf. http://www.rosary-center.org/ll55n6.htm: The Rosary Light & Life – Vol 55, No 6, Nov.-Dec. 2002, Fr. Raftery: the sacraments ‘continue’ the incarnation. ↩

- Cf. Pope John Paul II, Redemptoris Custos, 7. ↩

- I note the help of some comments by Fr. Etienne Nodet, Ecole Biblique, who suggested, among other things, the relationship between “Jesus’ celibacy” and “marriage as a vocation” (email, 27 March, 2014). ↩

- Although it is not possible to pursue it here, it is interesting to note that death was not a part of the original plan of God and, therefore, marriage was ‘forever’. This expression, ‘forever’, is used in Familiaris Consortio, (English translation; CTS edition, 2008): ‘that they may remain faithful to each other forever’ (20). ↩

- At http://www.jewishgateway.com/library/rituals/ (as of 19/10/11 Michael Fishbane notes, for example, the relationship between the Jewish marriage ceremony and the remembrance of the marriage of God and Israel at mount Sinai and the giving of the covenant. Furthermore, a ring is used in the traditional ceremony: “You are betrothed to me, with this ring, in accordance with the laws of Moses and Israel”. Nevertheless, as a conversation with Dr. Andrew Beards (at the Maryvale Institute at the time) brings to light (18/10/11), there must be a certain caution about establishing what was the practice and understanding of Jewish marriage at the time of Christ; rather, just as with anything, it is necessary to give the reflection on the Jewish rite of marriage and the Christian sacrament of marriage some scholarly foundation. Even so, however, it is clearly of some significance that Christ was present at an actual marriage, quite apart from the “symbolism” of such an event in terms of the significance of St. John’s theology of Christ’s mission (cf. Jn 2: 1-11). In other words, there is meaning to investigate at both the literal and spiritual sense (cf. CCC, 116-117) of this text. ↩

- Tobit, dated earlier by modern scholars but there is no reason given here, p. 920 of the Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Doubleday: New York, First Edition, 2009; indeed, Shalmaneser Vth was reputedly the one mentioned in the Book of Tobit, Shalmaneser, p. 833. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Deuterocanonical, pp. 213-214; and, as such, deuterocanonical comes ‘from the Greek for “second canon”’ and was first used in 1569. ‘Books regarded as canonical with little or no debate were called “protocanonical” (from the Greek for “first canon”)’ p. 213. The Apocryphal Books: Greek for “hidden things” and applied by the Catholic Church to books ‘that are often similar to the inspired works in the Bible’ but were not judged to be part of the canon (Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Apocryphal Books, p. 54). The Catholic Church recognised that Tobit, and the other books, belonged in the Canon of Scripture as enumerated in 1546 (Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Deuterocanonical, p. 214). Even if, then, there is some dispute as to its age and it is rejected by some, the Book of Tobit is nevertheless a part of a considerable body of references throughout the whole of Scripture and Jewish tradition to marriage (Consider, for example, the article in Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House Ltd., 1971: Volume II: LEK-MIL, pp. 1026-1054; and, in addition, Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Marriage, pp. 577-582). ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Tobit: “Prior to the 1952 discovery of Aramaic and Hebrew fragments of Tobit among the Dead Sea Scrolls in Cave IV at Qumran, it was believed that Tobit was not included in the Jewish canon because of its late authorship, which was estimated to be circa 100 AD. However, the Qumran fragments, which date from 100 BC to 25 AD and are in agreement with the Greek text existing in three different recensions, evidence a much earlier origin than previously thought.” ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halakhic: “Halakha has been developed and pored over throughout the generations since before 500 BCE, in a constantly expanding collection of religious literature consolidated in the Talmud. First and foremost it forms a body of intricate judicial opinions, legislation, customs, and recommendations, many of them passed down over the centuries, and an assortment of ingrained behaviors, relayed to successive generations from the moment a child begins to speak. It is also the subject of intense study in yeshivas; see Torah study.” ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book of Tobit/ ↩

- The Navarre Bible: Chronicles – Maccabees, General Editor, Jose Maria Casciaro, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2003, p. 324. ↩

- The Navarre Bible: Chronicles – Maccabees, p. 324. ↩

- In “Marriage and Divorce” by Michael L. Satlow, there is clearly an acknowledgement of the modern question of feminism and the rights of women, pp. 4 and 6; however, the question arises about the action of providence as understood and mediated by events for the benefit of both the man and the woman. ↩

- Navarre Bible: Chronicles – Maccabees, p. 327. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, John, Gospel of, pp. 459-460: Although there is dispute about authorship, there is both historical evidence and evidence from tradition that St. John was the beloved disciple who wrote this Gospel, even as early or earlier than AD 70; for example, owing to a reference to the ‘Sheep Gate’, ‘as though the city (of Jerusalem) was still intact at the time of writing’ and thus suggesting the Gospel was written before Jerusalem was destroyed in AD 70. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, John, Gospel of, pp. 459-460: Although there is dispute about authorship, there is both historical evidence and evidence from tradition that St. John was the beloved disciple who wrote this Gospel, even as early or earlier than AD 70; for example, owing to a reference to the ‘Sheep Gate’, ‘as though the city (of Jerusalem) was still intact at the time of writing’ and thus suggesting the Gospel was written before Jerusalem was destroyed in AD 70. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Matthew, Gospel of, p. 591: again reputedly written before the destruction of Jerusalem, such that “Suggested dates for the book have thus ranged from A.D. 50 to 100.” ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Matthew, Gospel of, p. 590, and 591. ↩

- Cf. Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1042. ↩

- Cf. Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1033, the bride and groom and by implication all others. ↩

- Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1032. ↩

- In “Marriage and Divorce” by Michael L. Satlow, p. 4; however, as with a lot of other things, there is a certain amount of controversy about these practices, e.g., what is the relationship “of this law to lived experience”? (p. 4). Nevertheless, the practice was obviously settled enough, from ancient times, for Goldberg to say ‘While this act (kiddushin, consecration, or erusin, or betrothal), establishes the legal bond of marriage, until the late Middle Ages, bride and bridegroom generally went on living in their respective homes for another year. Only then would the marriage be consummated. In ancient times, chuppah was the name given to the hut or chamber in which the consummation took place” (Goldberg and John D. Rayner, The Jewish People: Their History and Their Religion, London: Penguin Books, 1989, p. p. 375). ↩

- In “Marriage and Divorce” by Michael L. Satlow, p. 8, although later in this same article Satlow says: ‘’There is now wide (but not unanimous) scholarly agreement that there was little that was substantively and significantly different about Jewish marital and divorce practices in antiquity.’ This does not make sense if we are to understand a connection, implicit and explicit, to the Covenant between God and His people. Furthermore, while there may be some evidence of similarity between Jewish and non-Jewish law (cf. Satlow, pp. 5-6 of “Marriage and Divorce”), the very existence of the New Testament evidence (cf. Mt 1: 18-25) and its subsequent rabbinic elaboration (cf. Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1032; and cf. also http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14216-talmudic-law), speaks of both a real cultic practice and its enduring through time. In other words, there arises the question: why did this distinction between betrothal and cohabitation come to exist at all? ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Malachi, Book Of, p. 567. ↩

- Navarre Bible: Chronicles – Maccabees, p. 330, where the commentator is quoting from the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), 2197. ↩

- Although this speculation is not based on a particular source, as such, it is nevertheless the case that many Jewish marital practices are a kind of liturgical expression of biblically rooted “history”; for example, the elements of the ‘chuppah’ or the practice of the bride and groom being under a canopy ‘outside, under the stars, as a sign of the blessing given by G-d to the patriarch Abraham’ (http://ohr.edu/1087 : “The Jewish Wedding Ceremony” by Rabbi Mordechai Becher. ↩

- Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1032 etc. ↩

- Footnote 17 of Redemptoris Custos is to: ‘Paul VI, Discourse to the “Equipes Notre-Dame” Movement (May 4, 1970), n. 7: AAS 62 (1970), p. 431. Similar praise of the Family of Nazareth as a perfect example of domestic life can be found, for example, in Leo XIII, Apostolic Letter Neminem fugit (June 14, 1892); Leonis XIII PM. Acta, XII (1892), p. 149f.; Benedict XV, Motu Proprio Bonum sane (July 25, 1920): AAS 12 (1920), pp. 313- 317.’ ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Marriage, p. 580: “Traditional exegesis often states that Christ sanctified marriage by his presence at the Cana feast and by his contribution to the festivities (i.e., the good wine).” ↩

- Footnote 26 of Redemptoris Custos shows that Pope John Paul II is quoting from Pius XII: “26. Pius XII, Radio Message to Catholic School Students in the United States of America (February 19, 1958): AAS 50 (1958), p.174.” ↩

- Cf. A reading from the “Evangelical commentary” of Eusebius of Cesarea, bishop, p. 174 of Readings for Lent and Paschal Time, Volume II, Pro Manuscripto: For private circulation only. ↩

- Fr. Etienne Nodet, email, 27/3/14. ↩

- It is interesting to note that Michael L. Satlow, in Jewish Marriage in Antiquity, Princeton University Press, 2001, Chapter 1 published as a pdf on the web, says of Christ: “Where Jesus does evoke the image of marriage, the ‘marriage’ is between himself (the groom) and those who anticipate the kingdom of God” (citing a reference, 139), p. 24. ↩

- “St. Thomas Aquinas says there are two things which can order time and sense in Scripture. The first is that ‘human minds, existing in bodies, know first the natures of material things, and by knowing the natures of what they see, derive some knowledge of what they cannot see’ (STh I.84.7); and the second is that ‘nothing necessary to faith is contained under the spiritual sense which is not elsewhere put forward by the Scripture in its literal sense’ (STh I.1.10).)” (excerpt from an article by the author: http://www.hprweb.com/2012/01/scripture-is-a-unique-word/). ↩

- A consideration of the relationship between Christ’s vocation to celibacy and the “essenes” (Fr. Etienne Nodet, email, 27/3/14), although another line of enquiry, will have to suffice with the comment that if celibacy was beginning to show itself in a new and striking way, that this was a part of the general making ready for the coming of Christ which constitutes a part of this being the providential time. According to Satlow, for example, in Jewish Marriage in Antiquity, Chapter 1, p. 24: the Dead Sea community moved toward an “eschatological stance” wherein “procreative couples continue to be necessary in the here and now, but families will lose relevance in this next stage of history.” The evidence reviewed by Satlow entails the possibility of both married and celibate members of this community and a certain emphasis on the priesthood (cf. p. 24). In a more particular sense, then, there remain questions to be investigated; for example, although the relationship between John the Baptist and a tradition of Old Testament priesthood is well established (cf. Pope Benedict, Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives, translated by P. J. Whitmore, London: Bloomsbury, 2012, pp. 18-23), there is the question of how ‘the priesthood of the Old Covenant (epitomised, in a sense, in John the Baptist) moves toward Jesus’ (p. 18)? In one sense, Benedict begins to answer this question by speaking of Joseph as “son of David” and, as such, “he is to bear witness to God’s faithfulness” (p. 42). Nevertheless, given that the fullness of priesthood is, in a sense, what is unique to Christ (cf. for example, The Navarre Bible: Hebrews: Texts and Commentaries, translated by Michael Adams, Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1991, pp. 90-102), there are clearly many questions to be answered about the development of His self-understanding. In particular, how is the self-understanding of Christ’s priesthood “assisted” through his family life? ↩

- This quotation has excluded the footnotes in the original. ↩

- Satlow, Jewish Marriage in Antiquity, Chapter 1: In the course of reading Matthew Satlow’s opening chapter, which entails setting a part of the Babylonian Talmud’s discussion on marriage in its cultural context, there emerge a number of considerations that help us to understand a new relationship between the Holy Family and Christ’s vocation to celibacy. In the first place, however, this is clearly not the purpose of Satlow’s own study; rather, he has in mind, as I say, the contextualization of “two” strands of thought in the Babylonian Talmud: a Palestinian emphasis on marriage as founding a household (“oikos” “house” or “household”), the public good of this institution and that this is to act in accord with human nature (pp. 12-21); and a Babylonian emphasis on marriage as having a “covenantal significance” (p. 20), which entails understanding marriage as positively ordered to causing “God to dwell amidst Israel, and can even bring the Messiah” (p. 28), as a remedy to sinful inclinations and, therefore, to assist in the disposition necessary for men to study the Torah (p. 30). ↩

- Cf. the adage: activity manifests being. ↩

- Note also that the Catechism has included a section on the early life of Christ under the heading: “II. The Mysteries of Jesus’ Infancy and Hidden Life”(CCC 522-534), an innovation note by Cardinal Avery Dulles: “Although the creed skips from the birth of Jesus to his passion and death, the Catechism inserts at this point a section on the mysteries of the life of Jesus” (p. 49, “The Challenge of the Catechism,” First Things, No. 49, Jan. 1995, pp. 46-53). ↩

- Goldberg, “The Jewish People: Their History and Their Religion,” p. 371. ↩

- From the Hebrew word for “Listen” (Dt 6: 4); and, in general, I am indebted to a certain sensitivity to this word being applied to Christ through the liturgies and catecheses of the “Neocatechumenal Way” and being a particularly significant prayer in Judaism (cf. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shema_Yisrael) ↩

- http://www.jewfaq.org/barmitz.htm: can be one of the “the minimum number of people needed to perform certain parts of religious services, to form binding contracts, to testify before religious courts and to marry.” ↩

- http://www.biblegateway.com/resources/commentaries/IVP-NT/Luke/Twelve-Year-Old-Jesus-Goes where there is the point made that: “Jesus’ parents—and Luke’s readers—need to appreciate that Jesus understood his mission” (with reference to Lk 2: 41-51). ↩

- http://www.jewfaq.org/barmitz.htm ↩

- There is a summary of different aspects of this discussion at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origin_of_the_Eucharist ↩

- But note that there has been a revival of devotion to St. Joseph and that the Church has included him in the canon of the Mass after Mary (Pope John XXIII, quoted in Redemptoris Custos, 6) and, more recently, Pope Francis has extended the inclusion of St. Joseph’s name in all the canons of the Mass. ↩

- Cf. Scott McKellar, “Taking on the “Smell of the Sheep”: The Rabbinic Understanding of Discipleship”, The Sower, April 2014, Vol. 35, No 2, pp. 8-9. ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeshiva, more literally the word means “sitting.” ↩

- A Reading from the “Catechesis” of St. John Chrysostom, bishop (Cat. 3: 13-19) p. 317 of Readings for Lent and Paschal Time, Vol. II, pro manuscript: For private circulation only. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Corinthians, Letters to the: 1 Corinthians, p. 164. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Ephesians, Letter to the, p. 246: Assuming Pauline authorship, unquestioned for “seventeen centuries,” this and other “captivity Epistles”(e.g. Colossians) “can be dated approximately to the early sixties.” ↩

- Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1027; and cf. Michael L. Satlow, Jewish Marriage in Antiquity, Chapter 1, p. 25. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Marriage, p. 582. ↩

- Encyclopeaedia Judaica, Marriage, p. 1028. ↩

- Catholic Bible Dictionary, General Editor: Scott Hahn, Marriage, p. 582. ↩

- Goldberg, The Jewish People: Their History and Their Religion, p. 377. ↩

- http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=STD9bY_EySkC&pg=PT89&lpg=PT89&dq=Christians+do+not+share+their+marriage+bed+nor+expose+their+infants&source=bl&ots=FMoMBQeT8Y&sig=-_NeAFkTchXhL4f6WOMHMD5RTdk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=o341U4vWCe2B7Qbr34D4Cg&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=Christians%20do%20not%20share%20their%20marriage%20bed%20nor%20expose%20their%20infants&f=false ↩

- William Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, Vol. 1, selected and translated by W. Jurgens, Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1970: pp. 26, 451: b.50 and d. 98-117. ↩

- Cf. Pope Benedict’s discussion of how Old Testament language can be both explicitly and implicitly drawn upon, p. 15 of Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives. ↩

- Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, ed. N. Tanner, 2 vols. (1990); and in two conversations with Fr. Norman Tanner, it was clear that these early councils treated of the “problems” that had arisen and, therefore, presupposed a continuous and actual tradition of action and liturgical practice (26-27 March, 2014). ↩

- http://ancientfaith.com/specials/svs_lectures/st_john_chrysostom_and_married_life 5/11/11 ↩

- Goldberg, The Jewish People: Their History and Their Religion, p. 371. ↩

- http://www.tertullian.org/readfirst.htm 29/10/11 ↩

- To His Wife, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0404.htm 28/10/11 , Book II, Chapter 1. ↩

- To His Wife, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0404.htm29/10/11 , Book II, Chapter 2.%5 ↩

- To His Wife, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0404.htm 28/10/11 , Book II, Chapter 8. ↩

- To His Wife, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0404.htm 28/10/11 , Book II, Chapter 8. ↩

- Cf. Hans Urs von Balthasar, Mary for Today, Slough: St. Paul Publications, reprinted 1989, p. 35; and cf. Lk 1: 26-35. ↩

- This does not exclude other relationships, like that of John the Baptist, bringing the Old Testament priesthood to a certain development (cf. Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives, pp. 18-19). ↩

Recent Comments