The Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s

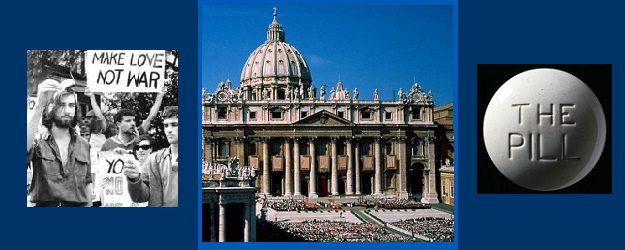

Americans have been living in an historical moment during which their existential awareness of what it means to be human has been drastically altered. Many of these changes are the consequence of a more extensive series of shifts in approaches to questions of morality, society, and work which began at the dawn of the Modern Era. A significant road marker in the trajectory of the Modern Era’s legacy was the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. This watershed moment in history has left such an indelible mark on the collective psyche of our society that it has made its way into the American legal system; this has been most recently attested to by the Supreme Court’s decision to adjust the legal definition of marriage so that this institution would be extended to couples of the same sex.

The Sexual Revolution stands in a truly provoking position beside the Catholic Church—it provokes all people in contemporary society to ask what is at stake in their lives, and what will most adequately satisfy their needs and desires. The fundamental vocation of all members of the Body of Christ is to respond to the true needs of all people of the world. This has been re-emphasized through the brilliance of a new light which has been cast by the Extraordinary Jubilee Year of Mercy. Our Holy Father Pope Francis asks us to continue our work of evangelization with a heightened awareness of our Lord’s tender embrace of sinners, with a renewed remembrance of his gaze of mercy. Francis calls the Church to be “a field hospital after the battle.”1 What does it mean for the baptized to be doctors, nurses, and caretakers in the aftermath of the battle that has been waged by the Sexual Revolution? To propose a worldview that is often characterized as being archaic and even hateful in our modern milieu would require us to approach this task with great attention and nuance. Our anxiety in front of a seemingly Herculean task ought to find consolation in the witnesses of numerous faithful Christians in the Middle East who are facing persecution at the hands of the Islamic State. Their willingness to die for the sake of the Faith is not born of a devotion to a political or moral ideology, but rather of an awareness of the true nature of reality and of humanity; which are contingent upon, and thus meaningless without, the Incarnation of God through his Son, Jesus Christ. It is here that we must begin to respond to the invitation that is the Jubilee Year of Mercy that we respond to the needs of a world so severely impacted by the aftermath of the Sexual Revolution: a witness by an exceptionally fulfilled humanity, born of a life lived for the sake of “Another.”

In order to better understand the essential foundations of the Sexual Revolution, it emerged, in part, as a reaction to a mode of expressing human sexuality that was increasingly accused of being “repressive” and “meaningless.” A largely “puritanical” moral worldview was accused of having reduced the human person’s horizon of freedom and fulfillment. The sexual revolutionaries wanted a way out of this restrictiveness. Supported by scientific and psychological evidence that aimed to prove that sexual repression caused damage to the human person, they defended a “free” expression of sexuality that rejected any moral implications: “sexuality is a pleasurable experience and nothing but that… The therapeutic task consisted in changing the neurotic character into a genital character, and in replacing moral regulation by self-regulation.”2 The Sexual Revolution was preparing to ring in a new era of utopia. The hearts of these revolutionaries longed for this moment after what they perceived to be a period of drought brought on by puritanical legalism, and a reductive definition of the human person. These revolutionaries responded to their thirsty hearts’ fundamental need for liberation by devising a moral worldview (or lack thereof) which corresponded to the need generated by a puritanical proposal of an incomplete, and ultimately repressive, moral worldview.

What does the proposal of the revolutionaries have in common with the proposal of the Church? After a time of a spiritual drought in the nation of Israel, brought on by the harsh legalism of the Pharisees and other hypocritical spiritual leaders, and ultimately by the dilemma of every human being’s sinfulness, Jesus offered “a river of Living water” to “anyone who is thirsty” (Jn 7:37-38).3 He came to “fill” the stomachs of those who “hunger and thirst for righteousness” (Mt 5:6).4 Christ’s offer to the human person fulfilled all legalistic and man-made offers of salvation and freedom. Thus, the proposal of the Gospel and Sexual Revolution have in common an offer to free a hungry, thirsty, and imprisoned heart from confining reductions of its deepest desires.

While these two proposals stand on some substantial common ground, they are miles—indeed, universes—apart when facing the question of what truly liberates the human person. Upon a deeper investigation of the roots of the Sexual Revolution, one will find that it emerged at a time during which the perception of reality (indeed, of all aspects of creation) had its origin in a Supreme Being, who is sovereign, and intervenes regularly in the lives of his creatures. But it was on its way to becoming obsolete. This phenomenon known as “secularism” has its roots in the dawn of the Modern Era. Fr. Luigi Giussani clearly articulates the nature of the dilemma this has brought about for those who still speak of God today:

God is reduced to a more or less private option, a pathetic psychological consolation, or a museum piece. For a man who feels keenly the brevity of his life and the many tasks to be accomplished, such a God is not only useless, but even harmful: He is the ‘opiate of the people.’ A society informed by such a mind-set may not be formally atheistic, but it is so de facto.5

Why did the revolutionaries choose an unrestrained expression of the sexual urge to replace the role of a divine Savior in their proposal? If it is true that there is no divine dimension to man’s fundamental make-up, then man is simply a “sum of his parts.” The Italian political philosopher Augusto Del Noce evaluated this turn from the Savior to the sexual:

…what is man reduced to, then, if not to a bundle of physical needs? When these needs are satisfied…{and} every repression is removed—he will be happy … Having taken away every order of ends, and eliminated every authority of values, all that is left is vital energy, which can be identified with sexuality … Hence, the core element of life will be sexual happiness.6

Human sexuality is one of the most concrete and powerful expressions of the true identity of the human heart: a yearning for the Other, a need for completion, and the fulfillment of the imago Dei. It is in this facet of the human person that she realizes that she experiences herself as incomplete without this “complementary Other.” Because the possibility of a transcendent Other was banished from their worldview, the revolutionaries’ secularized approach to human freedom had to come from the possibility to seek “completion” of oneself through sexual unity with whomever (and with however many people) they saw fit. The failure to recognize this mysterious Presence among us led to a tragic miscalculation of what defines the human person, and the extent to which his heart yearns for freedom, and ultimately, to the exaltation of man-made initiatives.

An ideology that deliberately seeks to rule out a crucial Factor of reality, that is, its Author and Sustainer, will inevitably do damage to the human person. Without the recognition of, and proper reverence due to God, one will begin to lose sight of her fullness and complexity as a human being; she will be confused as to how to live her life, and express herself. The reductive ideology that has been imposed on man by the Sexual Revolution has obfuscated the truths of gender differentiation and matrimony. The notion of the original human person as a complementary whole, consisting of two differentiated components, has been wearing away to the point that a person can choose arbitrarily to change genders, and to establish marital relationships, devoid of the complementarity that is essential to the human person’s fundamental make-up. As St. John Paul II reminded us in his encyclical letter, Redemptor Hominis, Jesus’ nature as fully man, and fully God, allowed Jesus Christ to “reveal man to himself.”7 The search for self-fulfillment can be realized through the gaze of him who is the Author of man, and who at the same time embodies the fullness of man. Within the relationship forged by his captivating gaze is the capacity to realize the Truth of one’s body, as differentiated through gender, and of his sexuality, as oriented towards its complementary Other. Thus the complete and extraordinary nature of Christ’s “revolution,” and proposal for liberation, is markedly distinct from that of the Sexual Revolution.

Having evaluated the proposals of the Church and the Sexual Revolution, and identified their common ground, as well as points of contention, we must begin the work of developing an appropriate response to people at “all the ends of the earth,” (Mt 24:14)8 on whom the Revolution has left an indelible mark. How can the Church fulfill the call to preach the Good News in a way that specifically seeks to treat the wounds of those slighted by the Revolution, in a way that heeds our Holy Father’s desire to emphasize our Lord’s gaze of mercy toward all people?

As we take a closer look at the essential content of the Church’s teaching on human sexuality, we may find a great deal of assistance in recalling the current experience of persecuted Christians living in areas controlled by the Islamic State. Their witness serves as a provocation to the rest of the Church to grow in a deeper awareness of the true nature of reality and of humanity. It provokes us to ask: could it truly be possible for modern men and women to live their lives devoted to Something other than themselves; to defy the expectations of a society that claims a rationalistic autonomy as its credo? The Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s touted said credo as the path to the liberation of our bodies and sexual desires from repression. The witness of the persecuted Christians in the Middle East ought to serve as a starting point for the Church at-large as it begins the work of evangelization during the aftermath of the Revolution. Our work of evangelization must be founded on a mode of living that expresses an exceptional awareness of what it truly means to be human. And because this work of evangelization must take into account the particular need to tend to the wounds of those living in the aftermath of the Sexual Revolution, we should look to these martyrs to educate us in understanding more profoundly what it means to live our sexuality and embodiment in conformity to the Gospel.

The marriage ceremony of the Byzantine rite richly illustrates how these martyrs can help us to understand this point. Toward the end of the marriage ceremony, the celebrant leads the man and woman around the sacramental table three times in what is known as the “Dance of Isaiah.” The hymn chanted alongside this dance makes reference to the crowns that were placed on the heads of the bride and groom earlier in the ceremony. These crowns represent the “rewards of the martyrs” for having “fought the good fight,” and thus are “giv{ing} glory to {God}.”9 In this hymn, we are reminded of what this man and woman are called to do in their marriage: ultimately, to die to themselves, and become united to Christ through their spouse. In this sense, they are replicating the heroic act of the martyrs, who literally die for the sake of union with, and glorification of, Christ. Thus, perhaps in a less dramatic way, the married man and woman are giving witness to the fact that the value and meaning of their marriage, and of human life as a whole, belongs to Something other than themselves.

Responding to those impacted by the Sexual Revolution, especially those who lack awareness of the extent to which it has impacted them, implies a great risk for the Church. Despite the desire to propose a beautiful Life, and to receive others in true charity, it is often the case that the those who do the work of evangelization, out of a lack of sensitivity, or simply out of their limited capacity to love others, do violence to those whom they seek to serve. Cardinal Ratzinger’s retelling of Søren Kierkegaard’s account of the clown and the burning village will aid us as we seek to identify our shortcomings, as well as potential obstacles in the work of evangelization. A clown from a traveling circus ran to the nearest village to warn the people that the circus caught fire, and was spreading in the direction of the village. He pleaded that they help put out the fire:

…but the villagers took the clown’s shouts simply for an excellent piece of advertising, meant to attract as many people as possible to the performance; they applauded the clown and laughed till they cried…{H}e tried in vain to get the people to be serious, to make it clear to them … that there really was a fire. His supplications only increased the laughter; people thought he was playing his part splendidly—until, finally, the fire did engulf the village.10

A significant temptation is to resort to reducing the Christian faith to a set of rules, values, and definitions. As much as these components play a crucial role in our Faith, they can be perceived as irrelevant, or even destructive, when divorced from the Christian Event which can only be known through a true encounter with the gaze of Christ. The religious person (“the clown”) today speaks about reality employing language that most people of today, at best, will laugh at, or ignore, and at worst, will decry as hateful and bigoted. Explanations of doctrines and moral teachings clearly are not sufficient to respond to the people who are living in the midst of the aftermath of the Sexual Revolution. Father Julian Carron, consultor of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, emphasizes the danger in yielding to such reductionism, noting how:

…(the) problem is that it’s not enough to repeat these words…Truth is not a definition, nor is it a doctrine that, simply because I affirm it, commands another’s freedom. If a definition is not something one has acquired in experience … then it is a schematic imposition, a formality; even a correct definition, if it is not understood in one’s experience, will easily be viewed as an imposition, and people will rebel against it. Christianity is not a definition. Truth is … a person.”11

Taking up arms by means of reiterating definitions and concepts, and preparing for an ideological battle, will inevitably prove to be futile. Employing these devices as the central means of proclaiming the Truth cannot be sustained, as they are merely human devices. No human attempt, no use of weapons, could possibly trump the power of a true encounter with Christ. In her article on the position of the Christian in today’s world, Melinda Selmys looks

…at the Culture Wars through the lens of Gethsemane … the battle that takes place in the garden: The problem with the image of the Christian soldier, the crusader, the Culture Warrior, is that this is not an image that Christ used, and when St. Paul used it, he was very careful to make it clear that “we do not war against flesh and blood.” The warrior culture that dominates so much of the Old Testament is transformed by the New Testament, particularly in Christ’s shocking statement “Love your enemy.”

Here, Selmys realizes how Christ is “armed” with a merciful gaze, a “big open heart,” which becomes a stumbling block to those who encounter him, including his own disciples. She then continues by saying:

Christ turns and utters the only military command in his career. “Peter, put down your sword.” Then, having rebuked his loyal and faithful follower, he turns to the man that Peter has wounded—the sole enemy casualty in this exchange, and he reaches out and he heals the ear of the servant of the High Priest … an enemy of Christianity. But Christ heals him.12

It is a paradoxical battle, won by a gaze of mercy; a contradictory willingness to love the enemy. It is this paradox that wins over the heart of men, and initially attracted Christ’s followers.

The U.S. government claims, in Obergefell vs. Hodges, that: “Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there. It offers the hope of companionship and understanding and assurance that while both still live, there will be someone to care for the other.”13 The human heart longs for a Companionship that greatly surpasses that which any other human being could offer. The true and complete fulfillment of the human heart’s longing lies not in a potential spouse, but in “He who truly reveals man to himself,” as John Paul II wrote in Redemptor Hominis §8. This desire for completion through a relationship with one to whom he is erotically attracted, serves as a sign of this greater longing. But ultimately, this initial longing is incomplete without being lived within the context of fulfillment on a supernatural plane. The Church must make clear that it promises a freedom that reaches beyond the capacity of the efforts of mere humans. Rather than take up arms ready to fight those who oppose the Church, we would be wise to heed the words of our Lord, and “put down {our} swords.” Our “secret weapon” is this winning attraction that no human force could overcome, but in which every human desire is completely fulfilled.

Father Carron proposes a method to begin an authentic evangelization by expounding on the role of our witness:

There is one thing we have to do, just one: to be converted, to let ourselves be won over once again by the fascination that is the only reason that we are here. Everything else is a consequence of this…the fascinating power of the faith–the conquering fascination of its unarmed beauty…”14

The Beauty of Christ is unarmed, it is not in need of defenses. The Beauty and Truth of our God-given sexuality is not reducible to the reciting of a definition. It is best expressed, rather, through a Person, that is, through the way in which Christians live their lives. Our witness depends upon our constant conversion of self to the Truth.

Cardinal Ratzinger continues in his discourse on the theologian as “the clown” by warning that

…if he who seeks to preach the faith is sufficiently self-critical, he will soon notice that it is not only a question of form, of the kind of dress in which theology enters the scene… Rather he will have to understand that his own situation {of facing belief and doubt} is by no means so different from that of others as he may have thought at the start. He will become aware that on both sides the same forces are at work in different ways.”15

Recalling the scene at Gethsemane, Melinda Selmys accentuates Ratzinger’s call to evaluate our “own situation,” that is our brokenness and doubt, our own need for salvation, and, in this case, the way in which we ourselves have been impacted by the Revolution:

When Christ reaches out and heals the High Priest’s servant, he does not see himself as healing the enemy. That’s our category, our perspective. He saw himself as healing the ear of the beloved: he had come to give his life for this man, just as much as he had come to give it for Peter.”16

While we may seek salvation from a Source outside of ourselves, can we truly claim to be so far removed from the category of “the sinner”?

Similar to a non-believer, the believer is subject to the same temptations of doubting God, and what he expects of us. He must stand with the revolutionary, asking with him the same questions, and point him to the possibility of a greater Truth. While many lack the awareness of the possibility of a broader horizon of fulfillment, they will only be able to begin to see that the true trajectory of their desire reaches the stars, the Infinite, God, if someone is willing to stand side by side with them on the battlefield, and direct their gaze upwards. It is here that we realize Pope Francis’ vision of the field hospital for the wounded warriors of the Sexual Revolution. His call to the faithful to act as “doctors and nurses” implicates our position standing by the side of those wounded, which exemplifies the paradoxical nature of our faith. God took on the form of man; he humbled himself, bringing himself to man’s level in order to raise up humanity.17 We must point to the Truth as medicine to serve our brethren, looking to our own brokenness as a means to share in their suffering; receiving them with the same gaze of mercy with which we were received by Christ. It is only in this gaze that our sinfulness can be perfected. Outside of this gaze, many will fear to look into the penetrating brightness of the Truth, of Christ’s perfection.

The fear in the hearts of those who have yet to experience this tender embrace is reflected in our society’s rejection of Truth. This is exemplified in the Supreme Court’s ruling on Obergefell vs. Hodges. Part of this ruling claims to console the “pain and suffering,” the loneliness and vulnerability, of people with a predominantly homosexual orientation, by offering them the possibility to have their homosexual partnerships recognized as a marriage by the government. As stated previously, this offer is severely reductive, and based on a miscalculation of the nature of the human heart, and of sexuality in general. But the vulnerability and loneliness to which it claims to tend is often a very real and painful reality for many. This emphasizes the need for a “culture of encounter.”18 Outside of the encounter with Christ, the Church’s teachings can be perceived as useless, and further damaging. Cardinal Ratzinger reminds us that “real dialogue” requires true “communication” in which “man brings himself into the conversation.” Only through this way can the presence of God emerge in a conversation. “…The testimony of God is inaudible where language is no more than a technique for imparting ‘something.’ God does not occur in logistic calculations.”19 Our hearts desire to encounter God’s presence among us, more so than to hear of God’s presence.

One person who can testify to the crucial need of an evangelization of encounter is Eve Tushnet. Ms. Tushnet, who experiences a homosexual orientation, was a former atheist, and did not agree with the Church’s teachings on homosexuality. Now, she embraces the Church as her true Home, and finds freedom in its teachings on chastity. She claims that she was only able to arrive at this point in her life because a community of Christians that she met sought not to explain to her why the Church’s teachings on sexuality are correct, but rather sought to receive her with simplicity and humility. Out of her attraction to these exceptional people, she began to accept the Church’s invitation to chastity. Tushnet explains how their patience impacted her conversion and commitment to chastity: “I think if they’d assumed that they were ‘supposed to’ witness to me by talking to me about God’s plan for my sex life, I would have been put off by the arrogance of their assumptions…When I did ask them {about the Church’s teachings on homosexuality}…they had the humility to do their best with the question I had pushed on them. I could respect that.”20 She began to recognize the attractiveness of the call to chastity precisely because of the witness of these Christians who were willing to stand by her side, and face these questions with her. The need to be doctors and nurses standing, side by side, with those who have been injured by the Sexual Revolution becomes especially momentous when considering the vulnerable place in which many people, with same-sex attractions, find themselves, including persecution due to ignorance, alienation, and the fear of a life lived without genuine companionship.

This is not to discount the efforts of those who seek to support civil laws that recognize the true value of human life, and the reality of our bodies. To dismiss the importance of these efforts would do a serious injustice to the call to witness to the Truth to the “ends of the earth,” which includes governments and worldly institutions. But these efforts can be neither the starting point, nor the core of our response, to the aftermath of the Sexual Revolution. These efforts must be born of the work of constant conversion, and not vice versa. What wins the battle being waged on the human heart is not won by an armed faction, but rather by an “unarmed Beauty,” a “winning attraction.” Thus, our hope lies in witnesses: those who proclaim through the way in which they live that human life belongs to, and is fulfilled by, Something beyond our calculations. We need a Church that is constantly returning to the gaze of mercy in which we initially encountered the One who won us over. Our continual conversion to this gaze is what will attract the revolutionary to that which will fulfill his desire for sexual freedom. We would be wise to heed the request of Archbishop Amel Nona, the displaced Chaldean Archbishop of Mosul, who was expelled from Iraq in 2014 while leading his flock in the midst of being persecuted by ISIS. In response to the question he was asked: “What can (the Church outside of Syria) do here and now?” He responded: “Live your faith with joy. We need to see your happiness.”21 It is the same paradoxical joy that these persecuted men and women possess, the same mercy that they express toward their persecutors, the same awareness of what it means to be human, and to live life exceptionally, that has the capacity to attract the hearts of all men and women when lived with intensity and authenticity.

- Spadaro, Antonio. “A Big Heart Open to God.” America (30 September 2013). Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Reich, Wilhelm. The Function of the Orgasm. New York, NY: Orgone Institute Press, 1942. Volume 1, selection 119. ↩

- John 7:37-38. New International Version. {Colorado Springs}: Biblica, 2011. BibleGateway.com. Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Matthew 5:6. New International Version. {Colorado Springs}: Biblica, 2011. BibleGateway.com, Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Giussani, Luigi. “Religious Awareness in Modern Man.” Communio. Vol. XXV No. 1. Spring 1998. ↩

- Del Noce, Augusto. The Crisis of Modernity. trans. Carlo Lancelotti. Quebec, Canada: McGill-Queens University Press, 2014. Page 160. ↩

- John Paul II. Redemptor Hominis §8. ↩

- Matthew 24:14. New International Version. {Colorado Springs}: Biblica, 2011. BibleGateway.com. Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- “The Service of Crowning-the Service of Marriage.” Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Ratzinger, Joseph. Introduction to Christianity. Trans. J.R. Forster. New York, NY: Herder and Herder, 1970. Pages 15-16. ↩

- Carron, Julian. “The Fascination of an Unarmed Beauty.” Traces (Vol. 16, March 2015), Web. November 15, 2015. Pages 15-18. ↩

- Selmys, Melinda. “Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane.” Sexual Authenticity. 16 October 2014, Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Supreme Court of the United States. Obergefell v. Hodges. June 26, 2015. Page 14. ↩

- Carron, Julian. “The Fascination of an Unarmed Beauty.” Traces (Vol. 16, March 2015), Web. November 15, 2015. Pages 15-18. ↩

- Ratzinger, Joseph. Introduction to Christianity, op. cit., 17. ↩

- Selmys, Melinda. “Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane.” Sexual Authenticity. October 16, 2014, Web. November 15, 2015. ↩

- Pope Francis. Evangelii Gaudium § November 24, 2013, Web. February 4, 2016. Par. 220. ↩

- Supreme Court of the United States. Obergefell v. Hodges. June 26, 2015. Page 5. ↩

- Ratzinger, Joseph. Introduction to Christianity, op. cit., 17. ↩

- Tushnet, Eve. Gay and Catholic. Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2014. ↩

- Perillo, Davide. “They Are Our Martyrs.” Traces Mag. Vol. 17, May 2015, Web. November 15, 2015. Page 7. ↩

Excellent article that really helps me understand more clearly Pope Francis’s emphasis on mercy and kindness. Selmys’s use of Christ in the Garden, the soldier not really being the enemy, is very insightful.

Well done, Mr. Adubato! I think that the comparison of the happiness offered by the culture, through the Sexual Revolution, and that offered by Jesus, through an encounter with Him, is a useful one for shedding light on the extent to which one may be unknowingly deceived by the secular mindset. You reinforce well the assertion that it is the encounter with Jesus that wins the heart. In the wake of such an encounter, mediated by a Church that lives out Jesus’ love and mercy, the “rules” become faithful guides that help the disciple to be extricated from the deceptive web of the thinking behind the Sexual Revolution.

Stephen – Congratulations on your publication! Wishing you all the best as you continue your studies. From a fellow students and now ICS alum Theresa Panzera

What an enlightening article/reflection this is! It certainly gave me both a set of ordained arguments on the subject and a great deal of food for thought. Thank you very much and God Bless!

This man teaches theology at a monastery?

With such confused ideas – or rather, soggy emotionalism?

I wish that you had talked more about the puritanism to which the “Sexual Revolution” reacted. Are there not strains within traditional Christian culture of fear and loathing of sexuality and the human body? Even today, don’t Islamic fundamentalists preach puritanism? Furthermore, haven’t there been traditions reducing women to baby-making machines or tools of male pleasure?

Thank you for the clarification of “those who seek to support civil laws…” I have noticed, in CL, what can at times be taken as a rejection of any sort of public stance or active engagement such as pro-life initiatives and political discourse. Of course this is not the starting point or the core, as you articulated well. However, I and others, at times, feel called to speak out for the truth of what we value, whether it be through public prayer or demonstrations. The defining feature is not the outcome, although a change is sought, but the expression of truth and the opportunity to be a challenge and presence to the prevailing situation (e.g. the “culture of death”). I have found that this can be done charitably, peacefully, and while it may be taken as hostility by some, it is a powerful witness to those who notice in silence.

At a recent discussion on the vacation, the term “activism” had such a negative connotation. Can someone help shed light on why?

First, what’s CL? Second, “activism” is a word that is pretty much owned by the radical left. It probably can’t be reclaimed, any more than the word “gay” can. Your approach is certainly a good one.