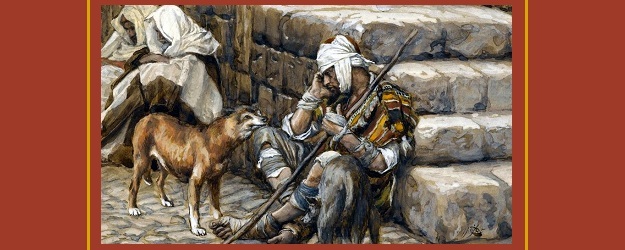

Lazarus at the Rich Man’s Door by James Tissot

In the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31), the parable begins with a description of the rich man and his life of luxury and excess. He is portrayed as a member of the elite, and would have been understood to be selfish. He would not have been expected to provide for Lazarus´ needs.1 With regard to the status of the rich man, his hospitality would have a pre-determined pretext of exhibiting and advancing his social position. A poor man like Lazarus would not have been helpful in this regard since he could not hope to reciprocate the rich man’s generosity. The rich man would naturally insulate himself from the needy to preserve his dominant position in society2.

Lazarus was not useful to the rich man, laying outside his gate. The rich man would not even acknowledge his presence since, to do so, this would place a stain on his status. Lazarus has nothing to offer, and is considered “unclean” besides this, with open sores being licked by dogs.3 Nevertheless, the story describes a scene in which Lazarus, while ignored, would have been noticed. St. Jerome wrote that Lazarus was laid at the gate, and not in a corner, making his presence apparent.4 Aphrahat, the Persian sage, wrote that Lazarus only wished for what the rich man considered garbage and, unlike the rich man, did not seek the best food or to fatten himself.5

A detail that tends to be overlooked raises the question: why was Lazarus laid at that particular gate? Luke does not explain why. In Acts 3:2, a lame man was laid at the Temple gate, but this was a public place. Also, in Luke 17:12, ten lepers approached Jesus seeking his mercy. Luke wrote that Jesus was entering a village, indicating that there might have been a gate that defined a specific entrance. While a gate is not specifically mentioned, it is clearly a public place. In Luke 14:21, a man tells his servant to go into the streets and invite the poor, the crippled, the blind, and the lame, suggesting the disabled and needy could be easily found there.6 In Luke 18:35, a blind man was seated at the side of the road. In Acts 14:8, a lame man was seated in the synagogue. Even outside of Luke’s writings, the needy can be found in public places. In Matthew 20:30, two blind men were seated at the side of the road. Also in Mark 10:46, the blind man, Bartimaeus, was seated at the side of the road, convenient to passersby.7 In John 5:3, the blind, lame and paralyzed, could be found at the Beth-zatha pool near the Sheep Gate. Whether they went to these places themselves, or were brought there, the disabled and needy were easily encountered in public places.

Again, why would Lazarus be in this particular place? Could the rich man’s gate be considered a public place where someone, like Lazarus, might be laid to beg for sustenance? The rich man’s daily feasts might indicate a well-traveled path to and from his gate. One researcher suggested that Lazarus may have been a laborer employed by the rich man. When Lazarus became too ill to work, he became useless to the rich man, but may have been brought to this particular gate with the hope that his former employer might help him.8 In verse 23, the rich man recognized Lazarus and knew his name, so there is some support for this theory. Also, since the wealthy were not known for helping people like Lazarus, a prior relationship, as I just described, might better explain why Lazarus was left at this particular gate.

Whatever the motive for Lazarus being at the rich man´s gate, he did not exhibit ambitious goals. As Augustine wrote, Lazarus only sought the refuse that the rich man would have discarded anyway, and expressed no desire to deprive the rich man of any of his accumulated wealth. However, even offering Lazarus garbage was too much of an effort for the rich man.9 Aphrahat, the Persian sage, added that Lazarus was an image of the humility of our Savior who waits quietly.10 It is ironic that Lazarus longs for the scraps that fall from the rich man’s table in his earthly life, while it is the rich man that longs for a drop of water that falls from the finger of Lazarus as relief from his torment in Hades.11 This reversal becomes apparent as the story progresses.

In verse 22, the scripture states that the rich man died while Lazarus was carried by angels to the bosom of Abraham. Because of his status, the rich man probably had a decent burial, with all the trappings associated with his wealth.12 The text does not state that Lazarus was buried and, in accordance with his social status, his body might have been discarded in the local heap of burning refuse.13 Augustine wrote that Lazarus was discarded and unburied, yet carried by angels, adding that a marble tomb did little good for the rich man, who ended up in torment14. Aphrahat, the Persian sage, commented that while Lazarus was cast aside and not buried, he was carried to reward by angels, and the rich man who was carried to his tomb with dignity, was cast aside into torment15.

This reversal after death becomes more manifest in verse 24. Upon seeing Lazarus reclining, the rich man as yet cannot let go of the privilege he had enjoyed. He asked that Lazarus be sent to him, still expecting Lazarus to be subject to his bidding.16 Expressing no regret for his lack of compassion for Lazarus when he was in need, the rich man expected Lazarus to leave his comfort, and cross over into misery to serve him.17 The rich man asked for relief that he was unwilling to offer Lazarus.18 He held onto the illusion that even in death, he could command Lazarus19 to act on his behalf. Accustomed to his spoken demands becoming action, the rich man’s commands are now powerless in Hades.20 Peter Chrysologus wrote that the rich man envied Lazarus who now held a place of privilege. He is envious that someone he had held in contempt now enjoyed happiness. His only thought is to relieve his tongue which, in his earthly life, only indulged in delicious food, never to command mercy or generosity.21 The rich man was not completely ignorant of his condition in Hades. He was forced to lower himself by acknowledging Lazarus, and pronouncing his name in a servile attempt to appeal to Abraham for mercy.22

The chasm described in verse 26 was not traversable in either direction, and was compared to the gate that separated Lazarus from a home in which scraps of food from the floor could have relieved his hunger.23 While the gate at the rich man’s house may symbolize this chasm later encountered after death, there is a great difference. The rich man could easily have eliminated this earthly chasm, if not to invite Lazarus inside, at least to send a servant to offer scraps he would have discarded anyway. What more likely represents this impassable chasm is the rich man’s own heart, which was too crowded with arrogance and selfishness to allow even the thought of bridging the gap between himself and Lazarus.

Realizing that he will not find relief, the rich man turns his attention to his brothers. It may seem that there is a ray of hope for the rich man who seems altruistic in his petition to warn his brothers.24 He wishes to warn his brothers, not that they pay heed to Moses and the prophets, but to avoid the torment in which he finds himself.25 This concern for his brothers is indicative of his own self interest, only looking out for his own.26 He is not concerned about the plight of the desperate poor, like Lazarus. He is only concerned with making use of Lazarus to warn his brothers.27 Gregory of Nyssa wrote that the rich man was still concerned with his earthly life, in contrast with Lazarus who was unconcerned with the past.28

Throughout this story, Lazarus does not have a voice. He is given an identity, and is described in the third person, but does not speak a word. As one who makes no demands, he is dependent on others. It is not known how he arrived at the rich man’s gate, either by his own desire, or left there by others. What this story can instruct us is that being charitable requires little effort. The rich man need not have gone out of his way to be compassionate. He only needed to look down by his own gate. This illustrates the saying, “Charity begins at home,” to which one could add, “Charity begins with a small effort.”

- Halvor Moxnes, “Patron-client relations and the new community in Luke-Acts,” in, The social world of Luke-Acts: models for interpretation, edited by Jerome Neyrey. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1991: 255. ↩

- Jole B. Green. The gospel of Luke. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997: 553. ↩

- Ernest van Eck, “When patrons are not patrons,” HTS Teologiese Studies 65(2009): 353. ↩

- Hieronymous, “Homily 86,” in, The homilies of St. Jerome, vol. 2. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 1966: 201. ↩

- Aphrahat. Les exposes. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1989: 794. ↩

- I. Howard Marshall. The gospel of Luke: a commentary on the Greek text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978: 590. ↩

- Joel Marcus. Mark 8-16: a new translation with introduction and commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009: 762. ↩

- Duane Warden, “The rich man and Lazarus: poverty, wealth and human worth,” Stone-Campbell Journal 6 (2003): 84. ↩

- Augustine of Hippo, “Sermon 24, “ in, Obras de San Agustín, vol. 10. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1965: 431. ↩

- Aphrahat, 795. ↩

- Bastiaan Wielenga, “The rich man and Lazarus,” Reformed World 46 (1996): 114. ↩

- Benson O. Igboin, “An African understanding of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus: problems and possibilities,” Asia Journal of Theology 19 (2005): 261. ↩

- Ferdinand O. Regalado, “The Jewish background of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus,” Asia Journal of Theology 16 (2002): 342. ↩

- Augustine of Hippo, “Sermon 142,” in, Newly discovered sermons. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 1997: 132. ↩

- Aphrahat, 796. ↩

- David P. Daniel, “22d Sunday after Pentecost: Lk 16:19-31,” Concordia Journal 11 (1985): 103. ↩

- Kenneth E. Bailey, “The New Testament Job: the parable of Lazarus and the rich man,” Theological Review 29 (2008): 25. ↩

- François Bovon. Luke 2. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2013: 482. ↩

- Wielenga, 111. ↩

- Warden, 93. ↩

- Peter Chrysologus, “Sermon 122,” in, Selected sermons. New York: Fathers of the Church, 1953: 210. ↩

- Robert Hurley, “Le lecteur et le riche: Luc 16, 19-31,” Science et Esprit 51 (1999): 74. ↩

- Walter Vogels, “Having or longing: a semiotic analysis of Luke 16: 19-31,” Eglise et Theologie 20 (1989): 30. ↩

- Hurley, 77. ↩

- George W. Knight, “Luke 16: 19-31: the rich man and Lazarus,” Review and Expositor 94 (1997): 281. ↩

- Regalado, 343. ↩

- José Cardenas, “Una parábola molesta (Lc 16, 19-31,” Qol 20 (1999): 71. ↩

- Gregory of Nyssa. The soul and the resurrection. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1993: 75. ↩

Recent Comments