The Eucharist is the single, greatest gift Christ left to his Church, fulfilling his promise to be with us always.

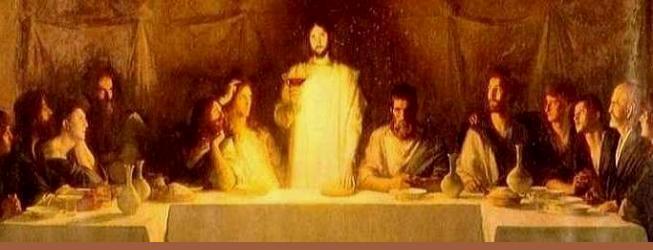

The Last Supper

Christ’s institution of the sacrament of the Eucharist was, and is, the single, greatest gift he left to his Church. For, it is the fulfillment of his promise to truly be always among us: “And know that I am with you always; yes, to the end of time” (Mt 28:20). While there are, indeed, multiple and varied presences of Christ, such as: when two or three are gathered in his name; when the People of God gather to celebrate the Liturgy; when Sacred Scripture—the Word—is proclaimed; or when the priest acts in Persona Christi while administering and officiating at any of the Sacraments, etc. The abiding Eucharistic presence of Christ, with the fullness of his Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity is truly singular in its reality, intensity, substance and fullness.

While the accidents of bread and wine remain, the substance is completely transformed into the Second Person of the Trinity. Holy Mother Church refers to this supernatural process—whereby our gifts of bread and wine are wholly transformed into the true presence of Christ—as Transubstantiation. Thus, while the appearance of bread and wine remain, the substance has been wholly and completely transformed into the very substance of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity. This occurs during the Liturgy of the Eucharist, specifically during the priest’s prayer of consecration, and immediately following the Epiclesis. Regarding the wholly unique presence of Christ, contained within the pre-eminent sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, the Catechism of the Catholic Church has this to say: “The mode of Christ’s presence under the Eucharistic species is unique. It raises the Eucharist above all the sacraments as ‘the perfection of the spiritual life, and the end to which all sacraments tend.’ In the most blessed sacrament of the Eucharist, ‘the body and blood, together with the soul and divinity, of our Lord Jesus Christ and, therefore, the whole Christ, is truly, really, and substantially contained.’ This presence is called ‘real’—by which is not intended to exclude the other types of presence, as if they could not be ‘real’ too, but because it is presence in the fullest sense: that is to say, it is a substantial presence by which Christ, God and man, makes himself wholly and entirely present” (CCC §1374).

Lumen Gentium, the Second Vatican Council’s “Dogmatic Constitution on the Church,” refers to the Eucharist as the source from which all the Church’s activity originates, and the summit toward which all the Church’s activity is directed. Based on this essential teaching of the Council, which reiterated 2000 years of Church teaching on the Eucharist, we can come to understand that the Eucharist truly is the “central Sacrament” in the sense that the Eucharist is “the end to which all sacraments tend.” This truth fleshes out the reality that each of the other Sacraments, while possessing a specific purpose in their own right, ultimately serve the greater purpose of leading souls to full participation in the Eucharistic banquet. This is nothing short of a foretaste of the heavenly banquet, where we will participate in God’s own divine life. For example, while the sacrament of Baptism has the specific purpose of forgiving original sin, and imparting sanctifying grace, its greater purpose is to allow the baptized to fully partake of the Eucharistic banquet. For, unless one is Baptized, he or she cannot fully participate in the Liturgy of the Eucharist, and be nourished with Christ’s body and blood. Moreover, it is essential that we be nourished with this “bread from heaven,” because, as Christ himself states: “I tell you most solemnly, if you do not eat the flesh of the Son of Man, and drink his blood, you will not have life in you” (Jn 6:53). Just as it is with Baptism, so is it with all the remaining sacraments. Reconciliation makes it possible for us to return to the Eucharist after we have fallen. Confirmation imparts the seven-fold gifts of the Spirit to better prepare us to enter into the mystery of the Eucharistic Pasch. Matrimony pre-figures the great wedding-feast of the Lamb, referred to in the book of Revelation, with Christ as the Bridegroom, and his Mystical Body, the Church, as his Bride. Clearly, the sacrament of Holy Orders is primarily concerned with imparting sacramental “character” on the priest’s soul, thereby enabling him to act in Persona Christi, chiefly for the sake of celebrating the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This is where, of course, the Eucharist is made present, and with which the Baptized are spiritually nourished. Finally, there is the Anointing of the Sick, of which reception of the Eucharist, or viaticum (bread for the journey), is an integral part. Thus, it is quite clear that each of the Sacraments has, as its ultimate end, the facilitation of participation in the Eucharistic banquet.

As an aside, it most curious that many Protestant groups, especially fundamentalists—who tend to interpret almost all of Scripture in a most literal fashion—stop short of a literal interpretation of Christ’s teachings on the Eucharist, which they strangely regard as merely symbolic. Let us turn to Scripture itself to read with our own eyes just what Christ stated regarding the Eucharist. Beginning in Jn 6:48, and continuing in John, Jesus states: “I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give is my flesh for the life of the world…. Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man, and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is food, indeed, and my blood is drink, indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.” And then again, in Mt 26:26, the following is narrated: “Now on the night he was betrayed, the Lord Jesus took some bread, and when he had said the blessing, he broke it. And he gave it to the disciples, saying: ‘Take it and eat. This is my body.’ Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them. ‘Drink all of you from this,’ he said. ‘For this is my blood, the blood of the new covenant, which is to be poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.’” If fundamentalist Protestant Christians tend to interpret almost everything in Scripture literally, then why not these words of Christ?

Having addressed the above curious issue, let us now discuss the marvelous effects of a well-received Holy Communion. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that “The principle fruit of receiving the Eucharist in Holy Communion is an intimate union with Christ Jesus.” Moreover, the Catechism continues, Holy Communion “preserves, increases and renews the life of grace received at Baptism” (CCC §1391). Thus, this Living Bread, come down from Heaven, truly nourishes the divine life in our souls. Just as the body needs material food to be nourished, strengthened and rejuvenated, so, too, does our soul need the spiritual food of the Eucharist to nourish, strengthen, enliven and rejuvenate the divine life that is the soul of our soul.

Secondly, “the Eucharist cannot unite us to Christ without, at the same time, cleansing us from past sins, and preserving us from future sins” (CCC §1393). Reception of this sacrament increases our charity, and forgives us our venial sins. Simultaneously, in strengthening our charity, it facilitates our bond with Christ, making it that much more difficult to extinguish the divine life within us, through commission of mortal sin. Although Holy Communion does, in fact, forgive us our venial sins, we are not permitted to receive this sacrament if we have fallen into mortal sin, as the Eucharist is the sacrament of the living, or those in full communion with the Mystical Body, the Church. Forgiveness of mortal sins properly takes place within the context of the sacrament of Reconciliation.

What is more, the Eucharist builds up the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ, by uniting us through the bond of charity with Christ, the Head of the Body, and with the members of his Body. The Eucharist is the fulfillment of the Baptismal grace, which unites and conjoins us to the Church: “Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:16-17).

The Eucharist is also “A pledge of future glory.” A beautiful ejaculatory prayer, composed by the great St. Thomas Aquinas, and soon adopted by the Church, provides a catechetical summary of the Eucharist. It reads as follows: “O Sacred Banquet, in which Christ is received, the memory of his passion is renewed, the soul is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.” It would behoove us to commit this prayerful ejaculation to memory, as it wonderfully, and simply, sums up the most salient catechetical tenets concerning the Eucharistic doctrine. We are, however, chiefly concerned here with the final thought contained in this prayer. For, Christ pledges to “raise up on the last day” those who “eat the flesh of the Son of man, and drink his blood.” The Sacred Liturgy is an earthly foretaste of the heavenly Banquet, the wedding feast of the Lamb, spoken of in the book of Revelation. Thus, the coming of Christ in the Eucharist takes on an eschatological significance, as each Eucharistic celebration pre-figures the second coming of Christ—that eschatological reality for which the human heart ardently longs, as we pray with the Church: Maranatha! Come, Lord Jesus!

Finally, because Jesus is truly present, in an abiding fashion, with his body, blood, soul and divinity in the Eucharistic species of bread and wine, it is laudable to practice devotion to his Eucharistic presence in the consecrated and reserved host. A consecrated host should be placed in a monstrance, which should then be placed on the altar, preferably surrounded by candles and flowers, in order that the faithful might practice the pious devotion of Eucharistic Adoration. While it is theologically correct to say that the Eucharist is primarily meant to be consumed by Catholic Christians in a state of grace, solemn veneration of the Eucharist exposed is a most salutary and pious practice, encouraged by popes, saints and doctors of the Church. Eucharistic adoration can be seen as a response to Christ’s call to his disciples to “keep watch with [him] for one hour” (Mt 26:40)—hence, the origins of the practice of the Eucharistic Holy Hour.

The Passover: Christ as the Lamb of Sacrifice and the Pre-figuring of the Paschal Mystery

At the last supper, the single most important Passover meal ever celebrated, Christ manifested his identity as the Passover lamb of sacrifice. In the Old Testament, during the very first Passover, the Israelites prepared a sacrificial meal in haste, as they prepared to be set free from their slavery in Egypt. On this occasion, an innocent, unblemished lamb was sacrificed. The blood of the sacrificed lamb was placed on the doorposts of the Israelites houses, to save the firstborn males from death. The lamb, which was slain as a sacrifice to the Father, was then consumed by the Israelites to strengthen them for their journey through the desert, toward the Promised Land. Moreover, as the Jews wandered throughout the desert, they were fed with manna, a bread from heaven, which was divinely given to them by God on a daily basis. In the New Testament, Jesus is the unblemished Lamb of God, who offers himself as a sacrifice of atonement to the Father, thereby saving us from the death of sin and hell, setting us free from our slavery to sin. It is precisely his blood that saves us from spiritual death. Moreover, Jesus offers us his own body, which has just been sacrificed, to spiritually strengthen us on our journey through the desert of this life, as we make our way to the Promised Land of Heaven. Moreover, Jesus is the manna, the “bread from heaven,” that we are nourished with, on a day-to-day basis, according to the providence of the Father, and his unfailing solicitude for the spiritual, and material, well-being of each of his children.

Thus, to truly enter into the mystery of the Eucharistic Pasch, we need to turn our attention to the Old Testament narrative of the very first Passover meal. Only then, will we begin to understand, however superficially (after all, this is a mystery of the deposit of faith): the tremendous significance of our Eucharistic Passover meal—the sacrifice in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass; and the grand mystery of Christ’s infinite, perfect, merciful and, sadly, often unrequited, love for humanity—in his real presence in the Eucharist.

[…] Central Sacrament Pre-Figured in the First Passover – J. M. Brunelle M Ed CAGS, H&PR […]