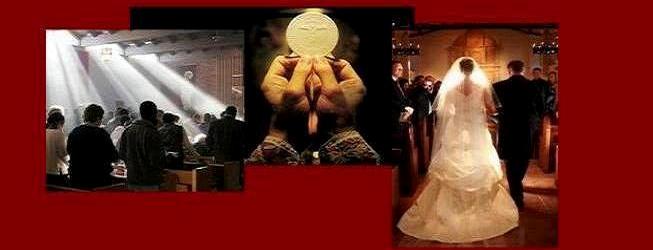

The Eucharistic celebration is a testament to the need for man’s self-gift as response to God’s gift to us through his Son …. to find himself through his own, sincere gift of himself … reflected in his total consecration to God through an earthly marriage.

Of great significance today is the issue of divorce, of increasing concern in our cultural landscape. In a world so broadly influenced, and ministered to, by the Christian mission of “love” and “unity,” many wonder at the reality of this growing divide at the heart and very core of society: divorce within the family. In his 2010 article, “The Era of the Narcissist,” Aaron Kheiriaty states:

Christianity was the leaven that shaped a more humble and humane culture; gave rise to America’s founding values; and, ultimately, prevented us from worshipping ourselves. The cure? Either we will become the salt and light that purge and dispel the insipid narcissism that surrounds us, or our culture will continue to descend deeper into the loud, crass, and aggressive cult of self-worship. 1

In this quote by Kheiriaty, we see the depth of our cultural crisis: narcissism. Our society, with its abundance of divorce statistics, has become more selfish and, therefore, undercutting self-giving. The very foundation of Christianity, of the Church, and, indeed, the Eucharistic liturgy, is about self-sacrifice. But our society is often referred to, now, as a “culture of divorce.” It was nearly 80 years ago that the author, Odo Casel, anticipated the problem and outlined a remedy for our marital crisis. Though Casel does not extensively discuss the sacrament of marriage, per se, his insights of the power of the liturgy are extraordinarily helpful in restoring man’s understanding of his origin and purpose. Controversial within his lifetime, this publication was widely accepted and influential in the crafting of the “Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy,” of the Second Vatican Council, in December 4, 1963. In his book, “The Mystery of Christian Worship,” Casel considers three points concerning man’s relational nature:

1. Man’s desire to belong to another;

2. Man’s sacramental life;

3. Man’s desire for objective order; all of which call out to him from the eternal and everlasting marriage.

The Eucharistic celebration is a testament to the need for man’s self-gift, as a following of, and response to, God’s gift to us through his Son. It testifies to the need of man giving of himself completely, as Gaudium et Spes §24 cites, in order that he might find himself through his own, sincere gift of himself. This is also reflected in his total consecration to God, or self-donation, through an earthly marriage. In order, then, to protect the dignity of this union against divorce, there must be a constant purification of the liturgy, through man’s understanding of his participation in it.

Through original sin, man lost his innocence, his union with God, through original solitude and original unity. Man’s fallen nature interjects an overwhelming sense of selfishness and narcissism into the world. Reflecting particularly on original sin’s narcissism, man is led astray from understanding himself as a gift from God, as one whose life is also meant to be given away. This sin echoes through the weakening of marital self-giving, focusing on selfishness. In recovering self-gift, and the Mass, man remembers the promise of redemption through the self-giving of Christ, and the resurrection of the body into the everlasting marriage of Christ and the Church.

Belonging to Another: The Longing of Man

In the “Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy,” paragraph 10, it is stated that the liturgy is the “summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed, it is also the fount from which all her power flows.” Man’s deep longing is only fulfilled in God. Casel’s central teaching on the mystery directs the growth of a sacramental culture through the flourishing of the Eucharist, which leads man to living in the mystery. Living a life in the sacraments directs man’s longing, through the objective order of the liturgy, to union with God and his love. This life also prepares man for the ultimate marriage of Christ and the Church, within the Father, where all human longing will be purified and fulfilled. This love essentially embodies what married life is meant to be: an image of Christ’s union to his bride, the Church.

With the deterioration of the modern world outside of Christianity and the Church, the secular man looks longingly for mystery. Yet, he will never reach God through a society in which man worships himself. In the wake of the Renaissance—giving rise to a “self-divinizing heathendom,” subsequently destroying man’s consciousness of God as mystery—Christianity has been “looked upon so much as a mere juridical institution, a moral activity, a function of popular education, that the highest and finest desires and capacities of the human mind have only too often sought satisfaction elsewhere,” Casel insists. 2 The most disheartening fact concerning this reality is that man has lost sight of his most intimate desires and longings for God, subsequently abandoning the message of hope and eternal love within the Eucharist celebration.

Abandoning the liturgy, man has lost sight of a need for the objective order, “which places the whole man, not just reason or emotion, into the cosmos of relations to God, his author and his end.” 3 Yet, without the order and form of the liturgy as a proper understanding of the cross, we would have no knowledge of the content or measure of the sacrificial love within the union of Christ and the Church. We must, then, look to Christ, whom the Father sent, since it is “only the mystery of God which can heal the world again.” 4 Through such mysteries left for us in the participation of the sacraments, man is transformed in Christ, and returned to the Father with the fulfillment of his deepest longings.

Man’s Sacramental Life

Through the incorporation of baptism and the other sacraments, man carries the life of God within him, for he becomes a living member of Christ. Through baptism and confirmation, he is not merely man, but is rather transformed and divinized in God, in order to be God’s child. 5 Belonging to Christ, he may then make sacrifice to God in an accepted manner, since it is first made through Christ. Indeed, there is no relationship, nor religion, without sacrifice. “The last and most proper offering is man himself: the offering to God of man’s free choice of love; this is the only sacrificial gift which does not already belong to God in this fashion.” 6 Man’s sacrifice of himself to God, through consecration, or married life, follows the example of Christ’s perfect sacrifice on the cross.

Without Christ, man would not be able to make such a dignified sacrifice to the Father. God first needed to absolve man, giving him reconciliation from original sin, and descending upon him as Christ “so that the individual might dare to approach God once more.” 7 As quoted from Casel, the necessity of the mystery of worship requires a visible community which expresses:

…its inward oneness, and its harmonious action in God’s service, through a common ritual act. An act common to God and his human community can only be properly carried out in a symbolic action, where priesthood (as mediator) takes both God’s part and the people’s, and gives outward expression by words and gestures to the will of both; thus the invisible action of God upon man is made known through the symbolic action of the priest, as is the deed of the worshipping community in the words and gestures which the priest employ. 8

These requirements are fulfilled in the Church’s sacrifice of the Holy Mass. Through the priest’s ministry, the church is able to carry out the mystery, offering her bridegroom’s sacrifice as her own sacrifice, “so that she becomes one sacrifice with him.” 9 Through the mystery of the Holy Mass, the Church takes her share in the passion of Christ. Although after him there is no new sacrifice or healing, “the church still wants to give testimony of her love, through a sacrifice; she wants to make the gift of her love to the Father, in a tangible, symbolic form.” 10

Man’s Desire for Objective Order

While God has come down to give us this great testament of his love, man has not always held it in the greatest, deepest respect. With such disregard, man not only undermines the eternal power of God, he also rejects the plan which God had intended for man from the very beginning. Reflecting on the present-day approach to the church’s worship, Casel remarks on the “devotion of a purely interior state of individual consciousness,” or narcissism. 11 Seeing this self-devotion continue into the present day, Aaron Kheiriaty states that: “In trying to build a society that celebrates high self-esteem, self-expression, and ‘loving yourself,’ Americans have inadvertently created more narcissists.” 12 This modern spirit has even pushed its way into the domain of theology, and has “showed itself in a weakening of the great, deep thinking of the older theology, emphasizing man, his reason and his self-rule, to the detriment of God, Christ, church and sacrament.” 13 Indeed, it is also to the detriment of marriage. A recent psychiatric study found that the “biggest consequence of narcissism was suffering endured by people close to the narcissist.” 14 The active sharing in the mysteries of worship, which flow from Christ’s life—including the sacrament of marriage as rooted in baptism—will only be really and truly fulfilled “when the Liturgy is known again for what it is at the deepest level: the mystery of Christ and the Church.” 15

All men are longingly desired by God. Christ emphasizes this in his preaching, as he named the “irreplaceable value of the individual soul.” 16 God’s desiring every man for himself, to be joined once again with him for eternity, is assisted in the Church’s effort in bringing every man into herself for this honorable cause. Thus, in the union of Christ and the Church, every man will be brought into this union with God: “As the woman was formed in paradise from the side of the first Adam, to be a helpmate, like to him, the church is formed from the side of Christ fallen asleep on the cross to be his companion and helper in the work of redemption.” 17

The development of mystery into liturgy can be seen in the sacraments, as through them, man is able to recognize God’s own action. In the example of baptism, the Lord “used the age-old forms mankind had always known, changing them and improving them” from having no natural worth of its own, such as water, and giving it symbolic value through his Word.18 So, too, with the sacrament and liturgical rite of marriage, with the coming together of two persons into one, we are able to recognize God’s own salvific action, which is meant to join him to his bride, the Church. In the new alliance, marriage is also wonderfully exalted, for now it is “an image of the spiritual marriage in the new covenant between Christ and his church … The primeval mystery is, therefore, the spiritual bond between Christ and his ecclesia, and the marriage of two Christians, which is a grace-giving image of that bond.” 19 As Christ and the Church go together to God, man and woman draw nearer to God through the Church in a sacramental marriage.

Each day, the Church prays, and in her, the “Spirit prays with unspeakable groaning,” for the fulfillment in eternal communion. 20 St. Augustine says that as “a lover sings,” the Church says of its love for God that“he has set my love in order.” 21 Both the longing of man, and the longing of the Spirit, for God, attains fulfillment through the objective ordering of sacramental life, rooted in the liturgy and the mystery of worship. It is rightfully understood that “the objective consciousness of community which the church possesses, submits the individual to a higher, God-given norm and gives it definite place.” 22 No other prayer can challenge that of the liturgy’s right in holding God’s truth, goodness, and beauty.

Conclusion

Recognizing the primordial actions of God through the sacraments, man realizes that he is an image of something greater than himself. So too, through the sacrament of marriage, man recognizes that his relationships are a sacrament of something much greater than anything he could create on his own. The foundation and strengthening of man’s sacramental marriage is, then, only confirmed and uplifted through the Sacred Liturgy, and the recognition for the need of his own unique sacrifice and self-gift. Articulating the longing of man’s heart to belong to another, Casel directs him to live a sacramental life through the objective order of the liturgy within the Church. He prescribes, as well, a “sacramental culture” as opposed to a “culture of divorce,” in preparing him for his share in the fulfillment in the ultimate marriage of Christ and the Church, in the Father.

- Aaron Kheiriaty, “First Things: The Era of the Narcissist.” February 16, 2010. ↩

- Odo Casel. “The Mystery of Christian Worship,” pg. 50. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 52. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 7. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 18. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 19. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 20. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 22. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 20. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 29-30. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 36. ↩

- Aaron Kheiriaty. “First Things: The Era of the Narcissist.” February 16, 2010. ↩

- Casel, pg. 36. ↩

- Aaron Kheiriaty. “First Things: The Era of the Narcissist.” February 16, 2010. ↩

- Casel, pg. 38. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 35. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 40. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 44. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 26. ↩

- Ibid, pg. 74. ↩

- Sermon 256, de Tempore. ↩

- Casel, pg. 81. ↩

Let me be the first to beat an old drum. If we want to recover self-gift, going out of ourselves to the other and especially the Other that is God, then we have a long way to go with our Sunday liturgies (not to mention our marriage ceremonies!). Daily mass is less of an issue, but our Sunday masses still suffer–at the experiential level–from the “closed circle” of a largely inward-looking community. This wasn’t mentioned in the article, but is the elephant in the living room. Until we change the music, rediscover silence and reverence, and direct ourselves primarily to God, we won’t have the love to feed our human relationships.