For Sunday Liturgies and Feasts

Homilies for March 2013

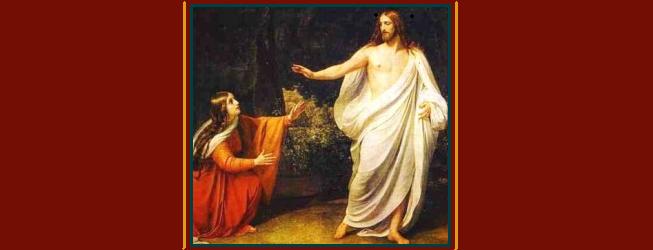

The Appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene by Alexander Ivanov

On Fire for the Lord

Purpose: When the Lord of all life draws near, we are to bear fruit. To flourish in his service is to grow ardent in charity but it is not to be consumed. We are made only in God’s image and likeness, so when we grow to be more and more like God, we actually become more and more ourselves, the people we were created to be.

3rd Sunday of Lent—March 3, 2013

Readings: Ex 3:1-8a ● 1 Cor 10:1-6, 10-12 ● Lk 13:1-9

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/030313-third-sunday-lent.cfm

He was in the midst of an ordinary day. Moses was tending the flock of his father-in-law, leading them across the desert, when he took notice of a bush that was on fire. That, of itself, wasn’t terribly unusual. On closer inspection, however, Moses was surprised to see that the bush, though on fire, was not being consumed. This, he rightly decided, was a “remarkable sight.” What is the meaning of this image? It becomes a bit clearer when we see this story of the burning bush of Exodus fulfilled by our Lord’s encounter at the fig tree in the Gospel of Luke.

The bush that is flaming, yet unconsumed, is an apt image for the Lord in many ways. The bush is at once wild and well-tamed; it is both ferocious and delicate; it is, in a certain way, inscrutable. The image, therefore, captures something of the essence of God, who paradoxically finds strength in weakness and plenitude in poverty. The life of God is one of total self-emptying, pouring forth without ever running the well dry. In fact, in Christ we see how strength is found only through weakness, life only through death, abundance only by thirsting for love and truth. This is the fruit he wants, this is why he pours grace into our souls: to bear life and to give him glory in our flourishing.

In the fig tree of Luke, chapter 13, we see exactly the opposite. For three years, the tree has produced no fruit. The person who planted it decides, quite reasonably, that the time has come to cut it down. “Why should it exhaust the soil?” The life of that fig tree was one of total self-gratification, leeching off the ground while giving no return.

Where do we find ourselves? It is so easy to become like the fig tree. Children can get so caught up in themselves that they become unwilling to sacrifice a little of their comfort for the greater good of the family. Husbands and wives can withhold themselves by contraception and so fail to offer the total gift of self, one to another. Men and women in public office can grow so focused on re-election that they neglect the concerns of their constituents. Priests can very easily fall out of the practice of prayer, becoming more vigilant for their own interests than for the welfare of their parishioners.

We are not called to be like the fig tree, however; none of us should settle for this type of parasitic behavior. No matter what our particular vocation is, every one of us is called to trust in God’s love enough that we boldly use the gifts he has given us to bear good fruit and contribute to the common good of his people. When we take a lot and give back very little, we are like the fig tree. The less we take, and the more we give back, the more we resemble the image of the Lord in the burning bush. In his mercy, the Lord is at work within each of us. He draws us slowly, and subtly, away from our fig tree tendencies; he draws us silently and steadily closer to himself.

The ideal of the burning bush is not beyond our reach. Each one of us has the power to make small, daily decisions to make ourselves resemble the bush more than the fig tree. When making those decisions becomes a habit, we will find ourselves on fire for the Lord. Perhaps today, we could preach on the Fruits of the Holy Spirit (and publish them in the parish bulletin), trying to get our congregations to see that the Lord wants more for us than simply not committing sin, but to become alive and on fire, bearing fruit that will last forever.

Suggested Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church: 736, 1830-32.

Be Reconciled to God

Purpose: The parable of the Prodigal Son is probably the most famous of all Jesus’ parables. It is so rich a story, that exhausting its meaning would be difficult. One good way of approaching the parable is through its three characters. If we look closely, we should be able to recognize ourselves in the younger son, the elder son, and even in the father.

4th Sunday of Lent—March 10, 2013

Readings: Jos 5:9a, 10-12 ● 2 Cor 5:17-21 ● Lk 15:1-3, 11-32

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/031013-fourth-sunday-of-lent.cfm

The key to understanding today’s Gospel rightly is to admit that every one of us is the prodigal son. Whether or not we have ever become mired in a rebellious, downward spiral of grave sin, we all know the basic experience of separating ourselves from another. Sometimes, we cut ourselves off from our parents, or our children. Sometimes, we separate ourselves from spouses, or old friends. Sometimes, we cut ties with God. We drift away into “a distant country,” until we eventually grow tired of our self-inflicted isolation and loneliness. By God’s mercy, we realize that we have forgotten our identity as his beloved children and, finally, wake up to his stupendous mercy.

There are also traces of the older son in us. Rather than wandering away, this son stays at home, yet he, too, becomes lost. This elder son is the type of person who did as he was told. He goes to work on time, doing his job faithfully. He is an obedient and respectful son. Regardless of his dutifulness, though, his heart becomes calloused. He separates himself from his family, not by fleeing to “a distant country,” but by walling up his heart, leaving himself imprisoned by unhappiness and resentfulness. When he sees his father’s joy at the return of his prodigal brother, he simply cannot abide it. His resentfulness reels when exposed to joy. This process is repeated in each of our hearts, when we feel forgotten and unappreciated, and we witness someone else being remembered and appreciated.

At different times in our lives, we have all played the part of these two singular, yet strikingly similar, sons. The destiny of our lives, however, is not only to be the lost child who is found by the father. What St. Paul calls the “upward calling” of Christian life is the supernatural process of becoming the father. In the father, we see an image of God himself, who actively seeks out the lost and the broken. As much as we may feel separated from his love—either by our prodigality, or by our sense of being overlooked—we never really are. The father loves both of his sons equally, and there is nothing at all they can do or say that will actually separate them from his love. This father demonstrates spendthrift generosity by going out to meet each of his sons in their need, and welcoming them back with heartfelt joy. Every Christian must imitate that example. In all the relationships of our lives, especially the difficult ones, the challenge of Christianity is to love with the same balance and effusiveness as God the Father.

The “fourth species” of pride for St. Thomas Aquinas is recognizing the perfections one has through God’s grace undeservedly. But in such recognition, is also the secret desire that the Lord share these perfections with no one else. This is how pride leads to envy in the order of the seven deadly sins. This is precisely where the older brother is at; he knows his father loves him, but is so scared to lose his unique status as the beloved that he is unwilling to let it be shared. This is one of the beauties of our Catholic intellectual tradition, namely, to recognize that only the little goods in life are diminished when distributed (e.g., food and material things), while the great goods in life actually increase when given away (e.g., joy, mercy, wisdom, love). Our Father in heaven can look at each of us and truthfully say, “You are my particular and unique beloved!” This is what the Father wants us to see at the end of this story.

So, at the heart of this tremendous parable is reconciliation. We, ourselves, first require reconciliation with God, and we are subsequently charged with the imperative to work toward reconciliation with our neighbors. In the words of St. Paul, God “has reconciled us to himself through Christh and given us the ministry of reconciliation. … We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God.” Reconciliation means not separating ourselves, like the two sons do. Rather, it means imitating the father by removing obstacles and restoring relationships.

Through prayer, it is possible to recognize the ways in which we resemble the younger and elder sons. Also, through prayer, it is possible to chart our progress on the path toward becoming the father. Only when we engage all three perspectives within this parable, will we be able to comprehend its marvelous message of mercy.

Suggested Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church: 589, 1443, 1846.

The New Law of Love

Purpose: To present Christ as the New Teacher who, from all eternity, has come into the human condition to show us something wonderfully novel: constant charity and unending mercy toward all.

5th Sunday of Lent—March 17, 2013

Readings: Is 43:16-21 ● Phil 3:8-14 ● Jn 8:1-11

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/031713-fifth-sunday-lent.cfm

As the saying goes, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” Is that true of God? It would seem that God is very old, even ancient. Can he be taught “new tricks”? Can he do anything new?

Listen to the bold assertion that God makes in the Book of Isaiah: “I am doing something new!” In the Lectionary, the boldness is even punctuated by an exclamation point. The Lord claims that he is capable of doing things that are new. Perhaps, the clearest evidence to support this claim lies in the life of Jesus, who came to fulfill the Law and the Prophets.

A prime example is recounted in the Gospel of John, chapter 8. There, the evangelist recounts an episode in which the Pharisees try to catch Jesus in an impossible situation. They bring him an adulterous woman, pointing out that the Mosaic law would have them stone her to death. They ask the Lord: “What do you say?” If he commands them to stone her, he will be accused of strict cruelty. Conversely, if he commands anything else, he will be accused of laxity. So, how does the Lord respond? He does something brilliantly new. “Let the one among you who is without sin,” Jesus challengingly says, “be the first to throw a stone at her.” In so doing, he cleverly shifts the focus from a convenient judgment of others, to a challenging introspection of self—from condemnation to mercy, from legalism to love. Just as the tablets received by Moses on Mount Sinai were said to be “inscribed by the finger of God” (Dt 9:10), so now Jesus writes in the sand “with his finger.” By imitating the revelation at Sinai, Jesus teaches the Pharisees that he speaks with the same authoritative spirit that underlies the Commandments of old. He reveals, moreover, that he is establishing a New Law, which is a law of love. He also shows that he has come to give us the Holy Spirit, the living “finger” of God (digitus Dei), and only in this Spirit can the true commands of God be lived—love and mercy.

Yet, some go away in their own self-inflicted shame, departing ashamedly, not being able to open themselves up to hear these words of Jesus’ tenderness. We must convince our congregation that if they ever feel mocked, or derided by guilt or their sins, this is not from the Good Spirit. Later, John (cf. 16:8) tells us the true Spirit of God has come to convince us of sin, but never to condemn us. Think of those root words: when con-demned, one encounters only the malevolence of their own perverted will, damned (damnare) in on themselves; but when con–vinced of sin, the Christian soul hears words of encouragement, and the graced overcoming (vincere) of what keeps them from wholeness. This is what is “new” in Christ’s encounter today: sin draws the love of God closer to the repentant sinner. Unlike the world that knows how to accept and, thus, appreciate only that which is whole, healthy, and perfect, the love of Christ is moved by the stumbling, and the indecisions, of the human heart. He has come to save sinners; he has come to found a hospital for the sickened soul, calling out for a savior. This is precisely what today’s Holy Communion line is: God’s ailing patients lining up to visit the only doctor who can cure us.

Jesus avoids being trapped by the condemnation of the religious professionals of his day through his wise, though enigmatic, response. There seems to be no hesitance on his part in establishing this New Law. The Lord shows that he is at once novel and traditional. He is unpredictable yet reliable. He is young and old. He is unchanging yet relevant. He is simultaneously surprising and steady. Ancient though he may be, the Lord remains always fresh, ready to work new wonders.

We are very fortunate to have a savior who does not feel bound to do things “the way we have always done them.” He is, after all, the bearer of Good News, and he is not afraid to shatter the expectations of the world. By his innovative response to the Pharisees, Jesus is able to spare the adulterous woman from the pressing crowd. Instead of being crushed by their stones, the woman’s sins were crushed by the weight of Jesus’ astonishing mercy. The Lord not only does something new, but he also gives her the opportunity to do something new. She is given the chance to live a new life, sing a new song, and walk a new path.

The same opportunities are available to us all.

Suggested Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church: 583, 700, 1847, 2840.

Choose Your Own Character

Purpose: The theme of Holy Week has been set: we are about meditation on the Lord’s Passion. It would be a profitable practice to extend this meditation deliberately throughout the coming week. Many people will attend the Triduum services later this week. Whether or not we are able to attend those special liturgies, though, this week is an opportunity to delve into the Passion. This is a sacred time, set aside to imagine the scenes of our Lord’s Passion, and to relive these ancient events anew.

Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord— March 24, 2013

Readings: Is 50:4-7 ● Phil 2:6-11 ● Lk 22:14-23:56

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/032413.cfm

For my own part, every year I like to choose a different character in the story and spend Holy Week trying to experience things as they would have experienced them. The goal is to choose a character that speaks to you. Maybe you want to spend some time as Mary, with all her special qualities as the mother of Jesus. Perhaps, you have been asked to do something you really do not want to do, and so you identify with Simon of Cyrene in the Fifth Station. Or, maybe you are struggling in your faith, so Peter appeals to you. Perhaps, you feel like G.K. Chesterton, who wrote a famous poem from the point of view of the donkey that Jesus rode into Jerusalem. Or, maybe a character you have never before noticed caught your attention at some point during Lent: Joseph of Arimathea, or Nicodemus, or Mary Magdalene, or Veronica, or the Good Thief. Wherever you feel drawn, try to imagine what Jesus looked like to that person, and how they felt, and what they might have been thinking. If we engage in that kind of meditation on the Passion, this week has the potential to be truly “Holy.”

Today’s homily will inevitably be shorter than most, given the length of today’s Gospel. One thing we might be able to accomplish, however, is to introduce this imaginative way to pray to our people. Invite them to pray about what they are feeling on this Palm Sunday. “As we look into our souls this august day, what do we sense as we stand before the Lord and his people? Are we anxious, indifferent, fearful, hopeful, fragile…? What is it we bring here this morning? Once people have had a little time to reflect, then we could help them connect this prevailing sentiment with one of the characters of Holy Week: Our Lord, for those feeling called to greater service; Our Lady, for those desiring to trust in God’s holy will just a little bit more; St. Peter, for those who want to fight the good fight but feel afraid of being found out by those around them, fearful for living out the Catholic faith to the full; for the fickle, or those feeling apathetic this morning, invite them to imagine they are the people who today shout “Hosanna!” but, come Friday, will be those shouting even louder, “Crucify him, crucify him!”

Praying like this, out of scriptural scenes, enjoys a long pedigree in the spiritual tradition of our Church. St. Ignatius of Loyola is probably best known for his Spiritual Exercises which invite the retreatant to enter passages of scripture using his or her imagination to see where it is they are feeling called to linger. Ignatius would advise anyone seeking to pray this way, and this is the perfect week to try it, to begin by considering “how God our Lord looks upon me.” What is it we are feeling, as we enter into our time of prayer. Next, “offer all my will and actions to God,” allowing the Lord to have me as I am right now. Finally, “ask God for what it is I now seek,” thus being bold before one’s loving Father, telling him what it is I most truly desire at this moment. With these preliminary movements of our soul, we are able to enter into biblical scenes with our own life’s movements and concerns. It is a way of making a “past” scene of the Lord’s life come alive in our own. As we then make our way through the biblical passage, say, imagining the Lord entering our town, our own homes, our hearts, we not only “review” the scripture in question, but we imaginatively enter the place, asking the Holy Spirit to lead throughout. We might then ask what I am attracted to in this scripture, and why; what repulses me in this scripture, and why. What is God teaching me here? In so doing, each of the baptized can make the stories, images, and persons of Holy Week their own.

Suggested Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church: 599-618; 2709-24.

He Saw and Believed

Purpose: In this Year of Faith, we are celebrating, as a universal Church, a virtue that has its origin in Easter Day. Were it not for the Paschal Mystery—the suffering, death, and ultimate Resurrection of our Lord—Christian faith would have no basis. The entire message of our Faith is made real this day: Christ lives as the Eternal Lord, having not only experienced, but has defeated, all that brings decay, sorrow, and death. Alleluia!

The Resurrection of the Lord: Mass of Easter Sunday—March 31, 2013

Readings: Acts 10:34a, 37-43 ● Col 3:1-4 / 1 Cor 5:6b-8 ● Jn 20:1-9

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/033113.cfm

When Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb, finding the stone rolled back, confusion falls upon her. She is so afflicted by the events of the last several days, that she came to mourn at Jesus’ tomb before the sun even rose. Seeing the tomb unsealed was very unexpected. What should she make of this scene? When she confronts Peter, and John, the Beloved Disciple, with the strange news, she says, “They have taken the Lord from the tomb, and we don’t know where they put him.” Can you picture Mary Magdalene in this state of confused, grief-stricken hysteria? All she can say is, “What happened? Which way did he go?”

The experience is very different for John. He runs with great speed to the tomb, indicative not only of youthfulness, but also of his anticipatory faith. When he arrives, John deferentially waits for Peter to go inside first. Notably, however, the Gospel tells us only that Peter “saw” the burials cloths folded and placed aside. Thereafter, we are subtly told that the Beloved Disciple “saw and believed.” Instantaneously, the series of events that confused Mary Magdalene, and perplexed Peter, is intuited. The Beloved Disciple does not get caught up wondering where Jesus has gone. He immediately thinks “of what is above, not of what is on earth.” He believes, on account of God’s gift and the evidence surrounding him, that “Christ is seated at the right hand of God.”

Shortly after this, the Apostles return home, leaving Mary Magdalene alone at the tomb. There, the Lord appears to her, becoming the first witness of the Resurrection. Before long, according to the Acts of the Apostles, Peter would be fearlessly traveling to “preach to the people and testify” that Jesus was “raised on the third day.” But it was John, Jesus’ Beloved Disciple, who first believed.

For this reason, the John is a tremendous model of faith. In this Year of Faith, we might ask what exactly is meant by this theological virtue. The Letter to the Hebrews defines faith as “the substance of things to be hoped for, and the evidence of things not seen” (Heb 11:1). The coming to faith of the Beloved Disciple was not merely the logical deduction of a sequence of events, unexplainable by any other means. Surely, another observer could have fabricated various explanations for what he, and Peter, and Mary Magdalene had each seen. The coming to faith of this Beloved Disciple begins with his acceptance of what Jesus had revealed about himself, ending with the John’s interior illumination by grace.

That Jesus could die on the Cross, and yet be raised from the dead, is the definitive motive of credibility. For one who has faith, the state of confusion never lasts long. Mary Magdalene, who began that first Easter morning in utter confusion, declares this in the sequence for today’s feast: “Christ my hope is arisen … Christ indeed from death is risen, our new life obtaining.” The Easter mystery serves as the bedrock for our faith, even as it did for the first disciples. At the sight of the Savior’s rising, and formed by the virtue of faith, we dare to say: “Alleluia!”

Suggested Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church: 638-55; 1168-71.

[…] we are to bear fruit. To flourish in his service is to grow ardent in charity but it is Source: Homiletic & Pastoral Review Category: Blogs and […]