Scholars tell us that this tipping point, when all taboos were uprooted and all universal expectations were discarded, goes by the name “Postmodernism.”

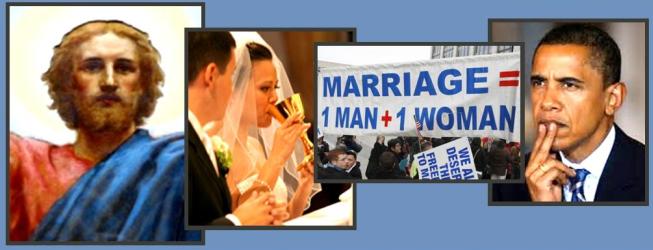

We have the sense that we went to sleep and woke up in a future we don’t recognize, surrounded by events unconnected to reality as we knew it. We feel like we are at sea in individual rowboats without any mooring lines or anchors. Most obviously these days: the traditional, monogamous marriage between a man and a woman, and the family, the bedrock of society for millennia, are under attack, the subject of ridicule and derision. Homosexual marriage, unthinkable a little less than a decade ago, is now blithely accepted in state after state.

To be sure, there is pushback from the Church and other defenders of traditional morality, but they are pilloried as bigots and ostracized as oddities. How did all of this happen? How is it that the scourge of nihilism appeared from nowhere and spread exponentially like the plague in Medieval Europe?

The answer is that it didn’t appear from nowhere or happen overnight. This stew has been simmering for a long, long time. There is a well-known anecdote to the effect that if you throw a frog in a pot of boiling water, it will immediately jump out. But, if you put a frog in a pot of lukewarm water, slowly turning up the heat, the frog will swim around in blissful oblivion, until it slowly dies. We 21st century Western Christians are that frog.

Scholars tell us that this tipping point, when all taboos were uprooted and all universal expectations were discarded, goes by the name “Postmodernism.” Although the average American has probably never heard the term, it is in the very air we breathe. What is it? Using the principles of Postmodernism, we can begin to define it by describing what it is not. Postmodernism is a successor of, and in many ways a rejection of, the philosophy of Modernism.

Modernism was the prevailing philosophy of the late 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries. Modernism was rational, empirical, and positivistic. It was rational because it held that truth could be discovered through reason. It was empirical because it held that truth could be demonstrated through the scientific method. And it was positivistic because it held that the correctness of a law came not from natural law or from Revelation, but from the will of the polity.

World War II disabused modern man of any illusions he had about the virtues of Modernism. Hitler was the ultimate positivist. His policies and actions were legal under German law at the time. In fact, one of the objections raised by some of the defendants at the Nuremburg Trials was that they were acting according to the present day German law. Hitler and his Nazi Party had enacted the laws. The result was the Holocaust, and the destruction of much of Western and Central Europe.

Although it had earlier roots, the philosophy of Postmodernism came of age in post-war Europe, with France as ground zero. The evangelists of Postmodernism were Frenchmen Jacques Lacan (1901-81), Michel Foucault (1926-84), and Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), and the American, Richard Rorty (1931-2007). But it was Jean François Lyotard (1924-98) who popularized the term “Postmodern.” In his book, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979), Lyotard states: “Simplifying to the extreme, I define Postmodernism as incredulity toward metanarratives.” That is, Lyotard saw how most people can no longer assume one “story” covers every life on his block—that everyone in his community worships or relaxes in the same way. How many of us just heard “Happy Holidays” to cover whatever feast one happened to be celebrating at the winter solstice, instead of “Merry Christmas,” which assumes all celebrate the saving Nativity of the Incarnate God?

Lyotard and others argued that one of the key markers of Postmodernism is “deconstruction.” As is common with Postmodern terminology, it eludes precise definition. But it means to take apart, or peel back, the layers of meaning in a text. Postmodernists hold that there is no inherent relationship between a word and a concept. Derrida held that all language is characterized by ambiguity. Foucault held that all language is an attempt by the user to exercise power over others. Thus, a text must be “deconstructed,” like peeling back the layers of an onion, to expose conflicting meaning. There is no longer “one” truth, one story.

That is why Postmodernists argue that the metanarrative—that grand story which attempts to explain all other stories by providing an overarching theme as the connecting thread—attempts to provide a framework of truth and meaning to all human events. The Bible is a very good example of a metanarrative. It is the story of salvation history of all peoples, connecting and providing meaning to other “stories” such as: Creation, the Fall, the Flood, the Covenants, the Prophets, and the Paschal Mystery. It answers the questions which all philosophers ask:

- Who am I?

- How did I get here?

- Where am I going?

- What is the meaning of my life?

For the Postmodernist, there is no truth. Words have no objective meaning. We each discover our own truth by inventing our own story. The question of whether or not the story is factually accurate doesn’t even arise for the Postmodernist; it is the story itself that counts. The story is our interpretation of reality, and it is as good as anyone else’s, because there is no “real” reality.

Most people don’t know what Postmodernism is, and that’s understandable. It’s the prevailing philosophy in academia today, but hardly anyone studies philosophy any more, so most wouldn’t be aware of it. But modern Western man is a Postmodernist. It’s in the air we breathe. It permeates our literature, our media, movies, television, even our conversation. It finds its way into our culture in subtle and not so subtle ways. Movements such as moral relativism, situational ethics, and various New Age modalities of spirituality, are all manifestations of Postmodernism. Postmodernism holds that there is no truth, only opinion, there is no objective right or wrong; in fact, there is no objective standard outside ourselves against which we can measure anything. Postmodernists are allergic to metanarratives, because metanarratives provide an objective framework to explain essence and existence. Postmodernists say that each person looks within himself, creating his own explanation by creating his own narrative.

In his 2011 book, Deconstructing Obama, journalist Jack Cashill calls Barak Obama the “first Postmodernist President.” His thesis is based largely on an elaborate and detailed exposition of how, in his 2008 autobiography, Dreams, President Obama constructs his own narrative which is inconsistent with numerous facts or dates from Obama’s own life. He does this, not because he is disingenuous, or a sloppy researcher, or a careless writer, but because he actually believes that facts are unimportant, each of us reinventing himself through his own narrative.

Why is all of this important? Because, as you may have noticed, those of us who are trying to defend traditional morality and traditional values are facing a very strong headwind. I submit that the reason that our arguments are not getting any traction is that we are using a different language, and coming from a different conceptual framework, than many of our interlocutors.

An example will illustrate the problem. In the recent debate in New York State over the legalization of same-sex marriage, the most common argument from the churches, and others trying to defend traditional marriage, was: “If you pass this law, you will be changing the definition of marriage!”

To which the most common answer was: “So what?”

In other words, we were saying that traditional marriage is instituted by God, and its definition, as the permanent union of one woman and one man for the purpose of the creation of new life, comes from Divine Revelation, and also from the Natural Law, and is, therefore, unchangeable.

The proponents of same-sex marriage, on the other hand, were saying: “Revelation and the Natural Law are metanarratives. We reject all metanarratives. We are free to redefine marriage, as we are free to redefine all things, as we please.”

I don’t claim to have the formula for successful dialogue with Postmodernists. The point I am trying to make is that in order to engage the culture on these issues, we do need to understand with whom we are in dialogue, and the framework from which they are operating.

Some basic principles of Postmodernism must be squarely opposed, such as: that there is no truth, no objective reality, and that words have no specific meaning. Postmodernism does, however, offer some useful insights with which we may make common cause. One of these insights is the rejection of the Enlightenment Project which saw knowledge as the source of salvation, and believed that universal education would lead to the perfect society. The horrors of World War II gave the lie to that fantasy. In that war, all sides employed the best intellectuals of their day to produce super-weapons. The result was the Holocaust, and the atomic bombs used against Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Yet, all sides appreciated Beethoven and Bach, Michelangelo and Rembrandt. Knowledge and education do not equate with virtue.

Also, Postmodernists argue that humans are more than just rational animals, that human life does, and must include, an element of mystery. We Christians would agree with that. The task of the cleric and the catechist is to study and understand Postmodernism, because it is here to stay, at least until the next “new thing” comes along. But, we must engage it in dialogue and learn how to use it to spread the Gospel—the greatest of all metanarratives.

‘…the Legacy of Postmodernism’.

Damn! Does that mean yet another -ism’s hit the dust? So short-lived :(

Or is it actually ‘the Legacy of Ockham’?

Thank you, Deacon. You summarize well the response of the secular world of today, to the beliefs and advocacy of the Church of today: “So what?” The difference between the two kingdoms, the two cities – the city of man and the city of God – become ever sharper and more distinct. At least to those having eyes to see and ears to hear.

You describe our stunned reaction well, also: “How did all of this happen? How is it that the scourge of nihilism appeared from nowhere and spread exponentially like the plague in Medieval Europe?” I am reminded of the powerful scene in the film trilogy, Lord of the Rings (The Two Towers), where King Theoden, finally arming for battle, ponders to himself: “Where is the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing? They have passed like rain on the mountain, like wind in the meadow. The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow. How did it come to this?”

So many in the Church remain sleepy, preoccupied, lukewarm in the things of God and far too animated by the things and loves and concerns of the world. “Where is the horn that was blowing?” Where are the warnings of the watchmen on the walls? Are they still, even now, taking their rest? When will the shepherds awaken to see the wolves gathering – wolves inside and outside, wolves wearing sheep’s wool among us and wolves arming for battle at the gates?

“How did it come to this?” It came to this one day at a time. How has the Church come to be so sleepy, preoccupied, lukewarm in the things of God and far too animated by the things and loves and concerns of the world? This too, one day at a time. Will we awaken? Will the shepherds awaken? Will the sleepy and the preoccupied finally become His Church empowered by His grace and His truth? Will we finally arm ourselves as we must, to meet the challenge coming upon us?

I have been reading a lot of Kreeft lately and it is this very point he has made over and over. There is no central foundation that those of this world are able to compare to, so, therefore anything goes. Our central foundation for the Catholic Church remains and shall remain until the end of time. We shall need a strong coat of arms to defend it I am afraid but we need to start being vocal.

Excellent analysis. The call to understand Postmodernism is well received.

Where we may be going astray is in tying our argument to the “objective” which is a faulty concept that leads to philosophical materialism.

If we study scripture, and then dive deeper into Catholic mysticism, we discover we live in a subjective universe. The “facts” we share are not objective but rather are inter-subjective, places where our subjective views meet and come into agreement.

An excellent account of this philosophy was put forth by Anglican Bishop Berkeley in the 18th Century.

Does this mean we do away with God and supplant the Divine with solipsism? No, not at all. As Berkeley discusses, God is the meta-subjective. His is the Will to which we conform our will, his Subjectivity is the aligning principle for our subjectivity.

Only in such an inter-subjective model do we find the ability to make sense of our free will and the urge to conform our will to His Will. Only in this model can we understand unity with Christ, in which our subjectivity becomes wedded to His as Word. Only in this model do we have the reality of God’s creation of the Word. Only in this model do we find an explanation for the relativity of the created world that stands in the shadow of the Absolute.

When we elevate the relative – the created world – to the status of objective absolute, we essentially create icons. Arguments for the objective always come up short and partake of the iconic. Thus, we must turn to an understanding of Idealism that recognizes both the Subjective and the subjective and recognizes the urge that pushes created subjectivity toward unity with Absolute Subjectivity.

This article addresses the understanding of a man who seems to assume the world is the West. The Church has moved south and east. We will now with Pope Francis begin to see the influence of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Whole new ways of conceptualizing reality will be discovered.

Well, you have defined post-modernism by its association with relativism, but in that vein, traditionalism is associated with universal formalism. Relativism is a style of thought that is a reaction to what relativists describe as the intellectual imperialism of universal formalism. That is, it is a reaction to the tendency of ‘traditionalists’ to state that their way of ordering the world is the only right way to do so.

Each of these styles of thought (relativism & universal formalism) has its own strengths as well as weaknesses. A third style of thought, dialectical thinking, is a blending of these two styles, so to speak. Basseches gave a good summary of these styles in his book ‘Dialectical Thinking and Adult Development’.

I believe the important point to maintain is that our faith should always be held outside our style of thinking. The Church has developed over the last two millennia through various stages, just as philosophical thought has likewise matured over that same period. But, regardless of how those developments proceed–for better or worse–we each remain responsible for our own faith and for the evangelization of that faith.

I often wonder what the 12 Apostles would think if we could bring them into our present. Would they view our post-Vatican II Church kindly or would their first thought be ‘heresy’? For that matter, what would their thinking be of the post-Vatican I Church, or of the 16th cent Church or of the 4th cent? Which truth is correct?

As Augustine wrote, “It is legitimate to think differently as long as communion is preserved.” Communion implies communication, and once we stop making assumptions about how others think, it becomes possible to find the common ground necessary for breaking bread together. Isn’t that the point of the Eucharist?

Not sure the dialectical approach gits er done. In some ways, it partakes of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, becoming stuck in the duality of the relative world, rather than turning to the unity offered in the Tree of Life. In a sense it is not transcendent. When we look at the path of transcending thinking per se and move into that region where Epistemology becomes coincident with Ontology, we come to “know” the Being of God through direct experience of our subjective awareness folding into The Subjective; we experience the product of our love encountering His Grace and Love. Dialectics gets left in the philosophical dust at that point.

There is a difference between what one believes is the truth and believing the truth is relative.

Wow. Welcome to the late 20th Century. I guess better late than never.

Thank you Deacon McKeating. You hit the idea of Postmodernism on target. I recall Pilates honest question to Jesus of ” What is Truth ? ” Jesus gave a metanarrative to Pilate who was given a revalation of the Kingdom of God but did not take it since his life style was similar to those who today askWhat is truth and proceed in nihilistic actions by ignoring first principles and transcendentals one, true , good and beautiful. And those who satisfy themselves by living together not as one man and woman but in a narcissistic state. . May God have mercy on those who do not have the truth of God.