The scanty conceptions to which we can attain of celestial things give us, from their excellence, more pleasure than all the knowledge of the world in which we live; just as a half-glimpse of persons that we love is more delightful than a leisurely view of other things, whatever their number and dimensions. (Aristotle, Metaphysics, 644b33-645a1)

But it is rather natural to a man of learning and genius, to apply himself chiefly to the study of writers who have more beauties than faults to be displayed; for the duty of criticism is neither to deprecate, nor dignify by partial representations, but to hold out the light of reason, whatever it may discover; and to promulgate the determinations of truth, whatever she shall dictate. (Samuel Johnson, The Rambler, Tuesday, February 5, 1751)

The title of this essay is admittedly odd. But titles are meant to call our attention to things that we might otherwise miss. What is cited above from Aristotle and Samuel Johnson manifests the spirit of where these reflections lead. By the “actual world,” I mean that which exists independently of man’s thinking about what the world is, or might be. Obviously, it is a paradox not to attend to the only thing that incites us to think in the first place, namely, what is out there, what is not ourselves. In a sense, two worlds confront us: the world as it stands by itself, and the world as we think about it and explain it to ourselves. Usually these two worlds clash only when what we think runs up against what is there. The usual result is that more than one “thought” world exists, but the world, as it is, remains what it is.

Up until modern times, this latter realization, that the thought world was corrected by a real world, was a barrier over which no sane person could cross. Madness actually meant living in a thought world that did not correspond to the real world. One way to eliminate the clash is to cease thinking. This logically meant a lapse into a silence in which nothing could be said about anything. This silence is what classical skepticism was about.

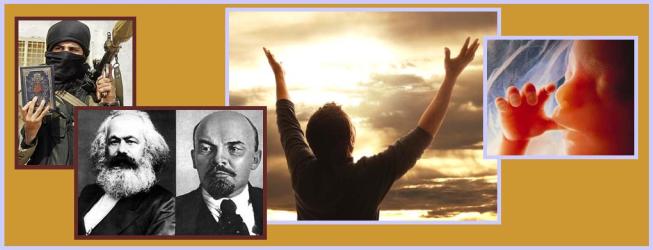

The other way is to eliminate the world, to postulate that no intelligibility, even residual, can be found in it. Once we eliminate the world that is, we are left with Pascal’s vast emptiness of spaces. We must replace or fill this emptiness with a world we fabricate ourselves. To be sure, some classic philosophies denied that the world existed at all, or that it was but another name for God. But modernity looks on a world, not in despair, but as open for human manipulation. Marxism, in particular, held that the world must be forcefully cleansed of all ideas or beliefs to assure that no reappearance of the gods will occur.

Three related observations might be added here: one concerning ecology, one concerning Islam, and one concerning Protestantism. Ecology is, in effect, a theory of state control of the human race based on the supposition that the purpose of man on earth is to keep himself going, as a species, if not as an individual, down the ages, for as long as possible. This view assumes a hypothetical knowledge of the total amount of physical resources available on the planet, and a divvying them out to a finite or ideal number of people allowed to live at a given time. Individual human beings exist for the sake of the ongoing species whose corporate good is the object of rule and existence. The purpose of thought, from this perspective, is practical, keeping the human race in existence for as long as possible.

Muslim thought, at least since the 11th century, follows a voluntarist metaphysics. Understanding Allah’s nature as capable of doing all things, even contradictory things, it followed that man’s relation to Allah was that of submission to whatever Allah might wish. If he told us to kill, we should kill. If he told us not to kill, we should not kill. If he told us both, we should do both. Our reason was not a check on Allah, nor his on ours. Since we could not be sure that what we saw in the world could not also be its opposite, there was no sense in investigating the world. Once this view became dominant, science dried up in Islam. If there are no stable secondary causes, science cannot exist. Since Allah could make everything the opposite, then it was blasphemy to think that things could not be the opposite of what they were. From this voluntarist perspective, our only alternative was submission. In this sense, the world in any meaningful sense, did not exist.

The rejection of Aristotle by Luther was an important aspect of this issue. Modern efforts to show that Protestants and Catholics meant basically the same thing by sola fides are helpful. Works needed faith to be salvific; faith that did not result in works was sterile. Nonetheless, the denial of some connection between reason and revelation had its consequences. Atheism and Protestantism agreed that no one could prove the existence of God from reason. The result of this view was that we had one world empty of God, and another one full of God. The atheist said, in effect: “Fine, we will take the world.” The Protestant said: “Take it, we will take God.”

The perplexed Catholic, who wanted to maintain both reason and revelation, argued that revelation was addressed to reason, but that reason had to be reason; hence the importance of Aristotle, as Pope Benedict XVI showed in the “Regensburg Lecture.” For the Catholic, the world’s order was not simply a void. It manifested an intelligence that the human mind was designed to discover. Revelation was given to perfect reason by making clearer the inner life of God, with his endeavors to redeem the human race through the Incarnation of the Son, and the sending of the Spirit. In this sense, an intelligible world, with an intelligent being within it, meets the original Logos in such a manner as to complete the purpose of the existence of both the world and man.

Technically, the world, about which, and in which, we think, should correspond to the world that is out there. That, after all, is what the classical definition of truth is intended to mean. Truth is the conformity of mind and reality. What the mind comes to hold is what is there, but after the manner of the knower’s own faculty. This faculty is not, and cannot be, simply another type of matter for it to do what it does, that is, remain itself and, at the same time, become the other. For a proposition to be true, we mean that our thought of something is, and we know that it is formed by, and checked by, what is actually out there. But what is there manifests its own intelligibility. The so-called “epistemological” problem—how do I know anything is there?—cannot be solved by some “proof” that would be clearer than the ordinary evidence we have of our senses and mind. This is why Gilson said that, in the beginning, we simply must affirm that “there are things and I know them.”

Initially, the mind, not the world, is a tabula rasa, an empty slate. This thing is this thing, not that thing. The world is filled with myriads of things waiting, as it were, to be known once they exist. The human mind does not cause them to be, nor does it put in them the intelligibility that it finds in things. It merely discovers that “this thingness” is already there. It then seeks to know what it is. It names it. Different languages have different words for the same things. Dictionaries exist, both to tell us what words mean, and what words are used by different languages for the thing we are interested in. This situation implies, however, that the cosmos itself stands, as it were, between mind and mind, the human mind and the mind that causes things to be what they are.

What I want to argue here basically is this: The reality of the world should be, and is, inspiring and awesome. Human intelligence is the conscious discovering and appreciating of what is. Truth only actively exists when a knowing subject actively knows what is not itself. But this world can, not without fault, become morally unbearable to many men. They choose not to live according to the reason, according to the truth and intelligibility found in the existing world, including that found in themselves, in their own very structure. Men are the only beings who knowingly look out on the world from within it and within themselves. Yet, they are not different from the world in the sense that what they are themselves belongs to, and originates in, the same reality that made everything to be what it is in the first place. No man made himself to be man, to “fabricate” what it is to be man.

We live in a world, with which some human beings are dissatisfied, because it is as it is. This fact indicates that a free and intelligent creature is capable of denying what he is. As a result, he may, but need not, rebel against the “being” that is given to him as a gift. Man does not cause himself to be—or to be what he is—in the first place. To think the actual world out of existence, then, refers to the philosophic steps whereby what is ceases to be the measure of the human mind. Thus, what is, is replaced by what I will the world to be. Or to put it another way, on this hypothesis, the only “mind” found in the universe is the human mind, logically “my” mind.

But this “new” mind, conceived as independent of things, is in the strange position of not having anything, even itself, as a solid foundation for what it is. A human mind, unrelated to any actual thing, can thus always be otherwise, something else—no real reason exists why it thinks this way, rather than that way. This not-having-a-definite-form is why it can always be otherwise—why the “reality” the mind knows by itself is never there without the sheer power of forcing it to say that it is there, whether it is there or not. In the end, this situation turns out to be but another form of voluntarism.

Yet, no one will admit that what he does is not really “right” or valid or true, even if its truth can contradict itself. Consequently, instead of correcting himself so that he returns to the reason in things as the criterion or measure of his mind, the modern atheist or relativist thinks the world itself out of existence. It is too much of a threat to the way he wants to live. He denies, in effect, that anything out there measures his own mind, or the actions that flow from it. He accomplishes this elimination in the only way he can do it, that is, by an act of the will. Once he has decided to go in this direction, he is, in this view, “free” to create his own “world.”

In this newly constructed world of man’s own mind, he is not bound by “reality,” by what is. He is only concerned with the configurations of the world in which he wants (or thinks he wants) to live. In effect, he has exchanged truth (the conformity of mind with reality) for artistic truth (the conformity of what we intend to make with what we put out there). The world then becomes the conformity, not of his mind with reality, but of “reality to man’s mind.” This result is the basis of the general understanding of “freedom” in the modern world. Man is not bound by anything but his own mind. His own mind is “free” to configure the world in any way that he wills. It is not truth—what is—that makes us free; freedom makes us whatever we want to be, whatever that is.

Atheism in the ancient world was largely a product of fear, in particular, of fear of the gods. The classical religious myths told stories of the gods fighting with one another, of their envy of man, and of their arbitrarily punishing him. Likewise, the gods lived pretty loosely. The good were often punished in the stories, while the bad were rewarded. The gods, in other words, were unfair. But why be fair, if it meant nothing and had no consequences? As a result, Plato’s brothers, in the Republic, wanted to hear justice praised, whether or not reward or punishment followed for living— or not living—rightly.

One way to escape this understanding of the world was to deny the validity of the gods of the city that embodied and preserved all these aberrations in the civic liturgies. A good and a justice higher than the city existed. The philosopher was more authentic than the politicians or the priests. In fact, ultimately the philosopher judged the city that rejected him. The crimes that were not punished in the city would be requited in the rivers of Tartarus. The soul was immortal. No one could escape his crimes without forgiveness and punishment. The world was not created in injustice, as it seemed just from looking at the ways men lived in any existing city. This proposal of judgment and punishment after death was Plato’s philosophic solution that saved the world from being a massive sea of injustices.

But the classical atheists, like Epicurus and Democritus, did not accept this philosophical alternative either. The ancient atheists, unlike the modern ones, were anti-city. They found what contentment they could find, not by being social, but by withdrawing from every city. They preferred a garden. There they could keep all such disturbing thoughts out of their hearing. If stories of gods and philosophers always ended up in causing worry, then ignore or deny both. Be happy in a very quiet and pleasant way. “Eat, drink, and be merry,” yes—but in moderation—as too much of even these pleasures could upset us. Human happiness could not care about the cosmos or the city. What went on in them only upset us if we worried about them in relation to our lives and conduct. Peace of mind depended on disregarding everything but what was immediately at hand.

Modern atheism did not think it could ignore the world, especially a created world that somehow expressed or reflected a creative mind that was not of the world. No one could deny that the world seemed to betray some kind of intelligible order. That is why the Greeks called it a cosmos and not a chaos. The trouble with this approach, particularly with its Christian origins, was that we can imagine a world coming from nothing. Indeed, the Creed itself implied that the world was created ex nihilo, from nothing. In this sense, believers themselves had to think the world out of existence even to appreciate what it was.

Once we understand that the world is not, in fact, itself everlasting, we can also postulate that everything evolved by chance. Even things that seemed always to appear in a definite order or sequence could supposedly be said to be “caused” by chance. This approach seemed, perhaps, plausible up until scientists recently began to notice that the world seems to have had a finite, temporal origin. Estimates were developed based on several approaches that the cosmos is some 13 to 14 billion years old. Moreover, such estimates were made because the cosmos manifested certain constants within an order. All of these stable constants seem to have been operative from the beginning. What has happened seems more like an unfolding of what is already there—rather than chance—though what chance there was seemed part of the same order.

If the universe has a beginning and manifests an order, it must logically follow that this order arises from outside the universe itself. In other words, “before” the beginning was nothing of the universe itself. But it does not follow that no intelligent source existed. Rather, it implies that such a source did exist and was not itself part of the universe. There seemed to be a cause that remained itself even while something besides itself came to exist. Reflection on such data suggests that the universe manifests an intelligible order that could not have been put there by the universe itself. The sidereal objects—the stars, the moons, the planets, or whatever—are not themselves intelligent creatures. They are not “gods.” What they seem to do is make the existence of intelligent creatures within the world possible.

But the intellectual creatures we know do not create their own intelligence. It is already there as part of the same order that brought the whole cosmos into being in the first place. Plato already understood some of this issue when he remarked that the world would not be complete unless there were within it beings that could look on it and praise it for its existing order. We see the same notion in the Psalms and other philosophic sources. We might call it the problem or purpose of finite intelligence. And clearly, if there is intelligence within the universe, that is, beings that can examine and understand what they see, it follows that the purpose of finite intelligence is itself to discover, and indeed acknowledge, the order of the universe and its origins.

But, once we begin to think of a finite origin to this cosmos, we cannot avoid thinking of its end. Is it to go on forever in the condition it is in, as modern ecologists seem to think? The same calculations that talk of the age of the various kinds of stars in the universe also talk of their ceasing to exist or collapsing into themselves. Some hypotheses, to avoid the creation issue, maintain that it all just starts over again to repeat the same cycles. Such notions are not unlike the reincarnation theories we have in several classics and other religions. But we have no evidence of this “restarting,” nor any reason why it might happen, short of speculations on the purpose of man in the universe.

A more pressing issue arises once we examine the arguments for the immortality of the soul, and even more so, for the resurrection of the body, which, in some sense, presupposes the immortality of the soul for it to be possible. It would seem, then, that the purpose of the universe is related to the intelligence manifested in the universe itself. Intelligence is open to finite intelligence, and the extra-cosmic intelligence we must postulate to explain the order in the universe itself. What revelation adds to these considerations is, at bottom, the reason why the two levels, as it were, of intelligence exist.

Revelation maintains that the origin of the universe is not in the universe itself, but within the Godhead, in the free Trinitarian decision to bring other beings into existence that could freely, if they so choose, participate in the inner life of the Godhead. This inner life was not “natural” to beings other than God. This fact meant that intelligent beings who were not God could only receive this divine life if it received the power to do so. But this possibility was what was offered to those finite, intelligent beings who found themselves existing in the actual universe. The drama of human existence that we know as salvation and redemption is but the carrying out of this purpose to associate man with this inner life. The world is essentially the arena in which this interplay between God and man is carried out. Its essence is the offering of, acceptance or rejection of, the kind of love that is found within the Godhead as its own reality.

In conclusion, what we do when we think the world out of existence in order to set up our own world is freely to reject being the kind of human that we were intended to be. Finite human persons were not only created to know and praise the world, but in due order, to participate, if they chose, in the inner life of the Godhead. The “logic” of modernity, if I might call it that, saw that no compromise was possible whereby we could retain God and do what we want. The latter choice required the evaporation of the world itself as the only sure way to guarantee our not being subject to an intelligence within the world and its origins outside the world. The irony today is that fortunately, or unfortunately, all the evidence seems to indicate that no alternate world that we postulate is superior to the one that is. In the end, a better world was brought into existence than any world we could propose for ourselves. In seeking to create a better this—world without God—we usually end up, as Benedict XVI said in Spe Salvi, creating our own hells on earth.

[…] The scanty conceptions to which we can attain of celestial things give us, from their excellence, more pleasure than all the knowledge of the world in which we live; just as a half-glimpse of persons that we love is more delightful than a leisurely view of other things, whatever their …read more […]