Since Christians are called to be Christ in the world … we have to allow Christ’s Spirit to embrace suffering in love within us, for without his Spirit abiding within us, we would never have the strength to suffer out of love.

Many of us hedge our bets when we choose to love. We put limits on our love. The rise of the “pre-nuptial” agreement is only one instance today. We are afraid that commitments will not satisfy us. We, therefore, tend to think that it might be best to “keep my options open.” We are afraid of what love costs. We are afraid to be disappointed, we are afraid that surrender to love may hurt, there might be emotional pain, and we look for ways to keep a door open to escape.

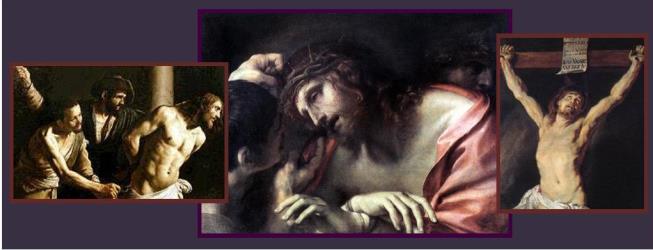

The cross of Christ, the cross to which he calls us, is the opposite. There upon the cross, Jesus commits himself to suffer for the salvation of his Bride, the Church, and no amount of temptation, fear, or pain can move him to be unfaithful. For us, his cross is a paradoxical symbol of repulsion and attraction. We know that in our deepest nature we are made to love, to surrender, to give without bounds; and at the same time, that sounds like death to us. So we hedge our bets and hold back. The cross is the place we want to go, but we’re afraid to go to that place of complete self-giving and love.

Jesus embraced the cross. He, goodness and innocence itself, chose to suffer such profound evil. On one level, Christ went to the cross so that we would know that suffering does not isolate us from God’s love. To believe that suffering isolates us from Divine Love is a lie that Satan likes to proffer during our vulnerability in sickness or pain. Christ, through his incarnation and cross, has entered every single aspect of human suffering. He is God with us, Emmanuel. The terrible way of dying, which is the cross, symbolizes all of the types of suffering that human beings can inflict upon one another, or that nature can inflict upon us. Jesus wanted every human being to know that in such suffering—whether it’s a health problem, or a painful relationship, or loneliness—he has entered into such human darkness himself in order to redeem it. He longs to bring us into the Light by way of communion with him. God, because he loves us, enters the human condition. He does not remove us from our human condition, but instead shares in it with us. Part of our condition is sin and finitude, which bring on suffering. Christ suffered the conditions of human life, and the inflictions that humans brought upon him, because he is Love. As then Cardinal Ratzinger said: “Whenever you think about God suffering, whenever you think about Jesus suffering, we immediately have to think about Jesus, God, loving. Because he suffers only because he loves.”

Since Christians are called to be Christ in the world, we have to embrace suffering in love as well. Or, better stated, we have to allow Christ’s Spirit to embrace suffering in love within us, for without his Spirit abiding within us, we would never have the strength to suffer out of love. So, in his Spirit, we, too, are called to carry the cross and meet evil with love. We Christians are not called to escalate evil, nor are we to be hopeless in the face of evil: we are called by grace to meet evil with love, to will the good in the face of evil. In the midst of this evil, the Christian will continue to commune with God, and out of that communion, he or she can love an enemy, receive an illness, stay faithful to an unfaithful spouse, and so on. We can meet any evil with love out of a secured communion with the Trinity.

This becomes the great witness of the Christian: evil cannot separate us from the love of God (cf. Romans 8). Even in the midst of horrific evil, love is still seen because the Christian bears love into evil, and evil is redeemed, by the grace of Christ. Meeting evil with love has to come from a supernatural power; it is not natural to human beings, and so we lean upon prayer to receive such a response to evil. We are called to pray, to open up our hearts and sustain our relationship with the Trinity. Evil always tries to isolate me saying, “You’ll never get through this. You’re weak, you’re bad, and you’re alone.” Prayer is the opposite of this lie; prayer is pure communion. In the very beginning of our spiritual lives, prayer may seem like “work,” but as we welcome Christ more deeply into our hearts, communion with him becomes our very identity.

Because prayer reaches down to my very identity when evil confronts me, I am able to withstand it out of the strength of the communion I have with God. In fact, for the holiest among us, evil can become an occasion for deepening intimacy with God since such intimacy is the refuge of those being taunted by evil. Some might respond, “How dare you say that God is with me in suffering, in battling temptation, since it feels as if God has abandoned me!” We remember that with the incarnation, God has entered into every aspect of our suffering. It feels and looks as if God has abandoned us in suffering because he has become one with it. Where perhaps, before the Incarnation, evil was a sign of abandonment by God, now even evil can be an occasion for coming closer to God through faith, hope, and love. If we approach any suffering in faith, it can be our time of visitation (cf. Lk 19:44). Prayer becomes a crucial virtue then, within which to meet suffering with love. To suffer in prayer is the way to undergo suffering’s deepest meaning and purification. Human life is filled with much suffering, so learning to pray is not ancillary to faith: “Wouldn’t it be nice if I had time to learn how to pray?” Prayer is constitutive to being Catholic. We must learn how to pray because we must learn to welcome God into everything that is ours, especially suffering.

If we welcome God into all things, aren’t we asking him to engage those realities we don’t want him to see, or we don’t want to engage ourselves? We are experts at hiding from love: it’s more natural for us to run from the truth than to embrace it (Gn 3:9-10). Many personal problems are linked to our not wanting God to know us. God is very gentle and persistent in his love. He comes very close and wants to ask us, “What are you afraid of?” A lot of times, our answer is, “I’m afraid of pain. So I really don’t want you getting too close to me, because then I may have to tell you the truth of my own self-hate, my own sadness, my own darkness, my own sins. I may actually have to tell you who I am. So let’s keep our relationship superficial, shall we?” But God is saying to us, “I want to come so close that you define yourself by my love for you. I know that’s frightening. But you can trust me because I have taken on your flesh and your blood and died your way of death. I did all of this, so you would know you are loved. Please look to the cross, and see that I let the human condition define me as a man. I took on everything you carry, and everything you are now hiding. Whatever you are carrying and hiding, I will cover in my compassion (cf. Jn 8:11). Do not be afraid to let me go deep, for to invite me close is the very definition of your happiness. And the longer you keep me from the deepest things of your heart, the longer you will carry your sorrows and grief by yourself” (cf. Mt 11:28). Of course, this isolation only compounds the sadness of the human condition. In a way, human beings are their own worst enemies. God wants to come close and, yet, we keep him at a distance because of our fear of suffering the change that love will invite.

This fear can be assuaged if we let ourselves be drawn to Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. In the garden, he stopped and faced his worst fears. So deep were his fears that he sweat blood (cf. Lk 22:44). There’s nothing more Christ can do. He is afraid and bears so much pain that his interior—the very symbol of life, blood itself—is now manifested on his forehead and drips down his face. He is at the very limits of the human capacity to suffer. Linger there in the garden with Jesus, and share with him all your emotional pain. One of the deepest human fears is the pain of loneliness. This fear of loneliness is what Christ is bearing right there in the garden (cf. Mt 26:40). We are called to get very close to Jesus in his tears: “No one understands me, and nobody accepted me. I feel like my life has been for nothing.” We want to get very close to Christ in the garden, we want our blood to mingle with his; we want our fears and doubts and difficulties to be shared with him. Jesus is not a magician; he’s not going to make human life effortless for us. But by sharing our suffering with him, he will deepen our relationship with the Trinity from within the human condition. The deeper we go into the truth of our human condition, hiding nothing from God, hiding nothing from ourselves; the more secure will be the effect of this honesty: secured intimacy with Love itself.

Jesus died a real death: he went all the way into this dark fear. Because we are so familiar with the story of Calvary, we don’t understand that he really went to the place no one wants to go. Ultimately, the Son’s relationship to the Father defined Jesus’ life, and so the grave could not keep him. We, too, like Jesus must go all the way into the human condition which includes death and suffering. It also includes this great mystery of love, intermingling with death and suffering. If we do not let Christ be close, if we do not know the living God, and love him, then our life will not be able to overcome death. It is impossible for us to pull ourselves out of death and suffering when it befalls us. We are, however, capable of inviting Jesus, who is Love and Life itself (cf. Jn 14:16), into the very midst of our deepest suffering. We are capable of saying to Jesus, “This part of my life is filled with pain and suffering. It’s the part of my life that I think is void of love. Could you go there with, and for, me?” And Jesus is saying, “That’s the exact reality into which I want to go. It is the exact point at which I want to enter human life. The point where you think you’re unlovable. You are lovable especially at the point of sickness, or rejection, or failure. Let me in there to be with you and heal you.” Here is the mystery of salvation; let Love and Life itself enter suffering and death so that suffering and death do not have the last word.

We all wonder why God allows us to suffer, especially if he loves so much. Mostly we suffer through our own fault however, through our own weakness, sin, ignorance, and pride. Human beings choose to resist what God wants to give: himself, his love. There is something broken in us, which, of course, is why we need the Savior. It is Christ who gives us the needed peace and healing. As much as there is suffering in the world—we can imagine all of our friends who are suffering now—we can also, at the same time, imagine all of our friends who are rising now as well. The paschal mystery is happening in its fullness throughout the Church every day. People are suffering, yes: but people are also being healed emotionally, forgiven, cured of disease, and raised out of poverty and want. People know broken relationships, but people are also reconciling. We suffer because of original and actual sin, but even now, in time, we can see that these do not define us. Each day, there are all sorts of bleak and dark events which give way to light. We are broken, and yet Christ is coming to heal us.

It is normal to fear suffering, to fear our crosses. For people of faith, our goal is to be able to allow Jesus to say in us: “Father, into your hands, I commend my spirit.” We want to grow to trust God. To trust that love is still present even though it feels like we’re alone. We’re not alone, if we invite these words of Jesus to enter us. Remember, he came to raise up the human condition, to raise up human nature, and secure its eternal participation in Trinitarian love. We align ourselves with this great mystery through baptism, through faith, hope, and love. The Father did not want to leave us orphans (cf. Jn 14:18); he wants to take us to his home (cf. Jn 14:3). Jesus wants to say these words over again in us: “Father, into your hands, I commend my spirit” (Lk 23:46). We are called to trust even though all things look dark. God is our father. He will not leave us in the dark, even though we must pass through it. We can pray, “Father, come and find me. Come and receive me. Bring me through this Passover into the light of your love.”

Stay with Christ, and you can face the cross. If we miss the weight of love upon the cross, we miss our only opportunity to fall in love with God, for no other reality contains the true intentions of God toward us, other than the cross. We are invited to contemplate the cross, the symbol of divine love for humanity, and then seek to mount it in our own circumstances in union with Christ. The intention of God toward us is to be with us in our suffering, to be with us within our own human nature, to be with us as One who loves us into his own happiness. He revealed this intention through the life, death, and resurrection of his Son. We have only to believe.

[…] Since Christians are called to be Christ in the world … we have to allow Christ’s Spirit to embrace suffering in love within us, for without his Spirit abiding within us, we would never have the strength to suffer out of love. Many of us hedge our bets when we …read more […]