While Apostolicae Curae holds that Anglican ordination does not confer the fullness of Catholic orders, this by no means implies that Anglican ordination is without its own value and purpose.

Many Catholic priests have followed with interest the establishment of a new canonical form, the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, to receive Anglican lay groups and their clergy into the Catholic Church. Repeated surveys have found that seven in ten Catholic priests agree that the Church “should continue to welcome Episcopalian priests who want to become active Roman Catholic priests, whether they are married or single.” 1 For many of these priests—and for many potential Anglican convert priests—the Church’s difficult decision that Anglican Orders are invalid has cast a pall over the Ordinariate. Inclined to generosity, aware that prominent theologians have disagreed with the decision, and that Anglican and Catholic worship are very similar, and recognizing their experience and maturity as pastors, these faithful men understandably question why these Anglican colleagues must be ordained in forma absoluta, as if their former Anglican ordination never occurred.

Yet, to do otherwise would be a serious mistake, pastoral generosity and respect notwithstanding. With the formation of the Ordinariate, the question of Anglican Orders has moved from ecumenical relations to the realm of pastoral and evangelistic concerns. In this new situation, I argue, absolute ordination creates the optimum conditions for the reception of Anglican priests into Catholic ministry while also respecting and valuing Anglican ministry.

In this article, I will present four main arguments to support this thesis. First, the decision on Anglican Orders rests on much stronger theological grounds than are generally acknowledged, reflecting not only Catholic thinking, but also the central tradition of Anglican thought. Second, the view that Anglican orders could be valid is especially inconsistent with Catholic conversion. Third, conditional ordination would place the Catholic Church, and the Ordinariate, in an untenable position regarding ordination decisions and could seriously impede the incorporation of Ordinariate clergy into the American Catholic Church. Finally, the absolute ordination of convert Anglican priests, properly understood, does not express a negative judgment, but rather a positive appraisal of the value of Anglican ministry. Before pursuing the arguments, it may be helpful to review briefly the history of the conflicted question of Anglican ordination.

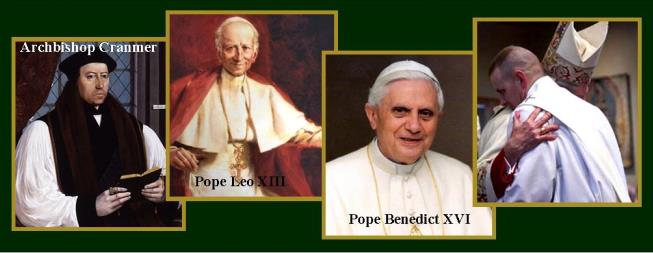

The conclusion by Pope Leo XIII’s 1896 document, Apostolicae Curae, that Anglican orders are “absolutely null and utterly void,” has, in the words of one observer of Anglican-Catholic relations, “cast a long and very dark shadow across our relationships and conversation for one hundred years.” 2 Many on the Anglican side, and some on the Catholic side, have rejected Leo’s stark repudiation of Anglican orders. Those on both sides, whether they concur with the decision or not, agree that it presents an insuperable obstacle to closer ecumenical relations between the two churches. Since the 1960s, leaders of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Consultation (ARCIC) have termed it the most deeply felt issue affecting their dialogue. In 1979, they boldly asserted that ecumenical progress “calls for a reappraisal of the verdict on Anglican orders in Apostolicae Curae.” 3

The issue becomes very personal for Anglican priests considering conversion, who often take pause or even offense at what is perceived to imply a negative evaluation of their Anglican ministry or orders, as if they were worthless or perhaps only a pretense. Giles Pinnock poignantly expresses this “deeply troubling” effect of the verdict of Apostolicae Curae: “Subjectively and emotionally, the denial of ‘my priesthood’ is for some Anglicans a serious obstacle presented to them by absolute ordination.” 4 Anglican ecumenist Callan Slipper observes that under Anglicanorum coetibus, “the orders of former Anglican clergy are not recognized, hence any reordination in an Ordinariate is absolute and not conditional.” He concludes that “{n}o amount of appreciation of the work of the Holy Spirit in a man’s previous ministry can deny this fact, and so a denial of the Anglican belief in the validity of its Church’s orders is implicit … 5 This requirement, in his view, is “indicative of a diminished Anglican identity” in the Ordinariate. 6

Older Anglicans can recall when it seemed that the Catholic Church may have been moving toward a more accepting position on Anglican orders. The ecumenical impulse within Catholicism, following the Second Vatican Council (1963-65), reduced the Catholic proscription of Protestantism generally. This was furthered by the achievements of ARCIC, during the 1970s, to reach consensus on other theological points; and the positive reappraisal of Anglican orders by some major Catholic theologians. These elements fed the hope that reconsidering the validity of Anglican orders may be on the horizon. The conditional ordination to the Catholic priesthood in 1994 of Graham Leonard, a senior Anglican bishop, seemed to confirm such thinking.

But then, in 2000, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), under Cardinal Ratzinger, issued the declaration, Dominus Iesus, a strongly-stated rejection of the sufficiency of Protestantism, which, to Anglican observers, “seem{ed} to reassert Apostolicae Curae, and to ignore the ecumenical gains of the past 30 years.” 7 The Archbishop of Canterbury responded: “Of course, the Church of England, and the worldwide Anglican Communion, does not for one moment accept that its orders of ministry and Eucharist are deficient in any way.” 8 In fact, though little noticed at the time, the nullity of Anglican orders had been explicitly reaffirmed two years earlier in an official doctrinal commentary released with the 1998 Apostolic Letter, Ad Tuendam Fidem. In this commentary, which addressed the degree of credence which Catholics should give to emergent teachings of the ordinary Magisterium, the CDF listed as an example of truths “which are to be held definitively … the declaration of Pope Leo XIII in the Apostolic Letter Apostolicae Curae on the invalidity of Anglican ordinations.” 9 Anglicans attuned to the effect of changing ordination practices—such as the ordination of women and experiments in lay presidency—on the prospects of rapprochement with Rome, had already predicted a swift reassertion of the rejection of Anglican orders. 10

Mutual Invalidity

The preoccupation with the Catholic rejection of Anglican orders in the past century has been accompanied by forgetfulness regarding the equally strong Anglican rejection of Catholic orders. Yet, the recognition that Anglican orders are not Catholic ones is not just a Roman Catholic pronouncement; it is also Anglican doctrine. Long before Pope Leo XIII declared, in 1893, that Anglican orders were deficient from a Catholic perspective, 11 Queen Elizabeth I, in 1570, declared the Catholic view of orders deficient from an Anglican perspective.

The central points of Anglican belief are stated in the Articles of Religion, which were articulated and revised over a period of several decades during the tumultuous 16th century. Although Catholic-minded Anglicans since the Oxford Movement of the 1830s have often questioned them, the Articles were clearly intended to be an authoritative statement of Anglican belief. Though today, they do not carry the same kind of juridical authority as Roman Catholic doctrine, originally they carried even more. Conformity to them among the clergy was originally enforced on pain of death. Until the 19th century, it was a requirement for civil office in England. They have been included in every edition of the Book of Common Prayer in Great Britain and North America up to the present day, and are routinely cited by participants in Anglican theological discourse as representing the mind of the church.

Initially intended to affirm Catholic teaching in the face of the Lutheran reform, in successive revisions, the Articles came to adopt Protestant, and even explicitly anti-Catholic, views. Beginning with six articles stating points of Catholic doctrine by King Henry VIII in 1536, they had been expanded to 42 articles incorporating Lutheran ideas by Henry’s Protestant-leaning son, Edward VI, by 1552. These were eventually pared to 39 articles in 1570—following a convocation and the excommunication of the Pope by Queen Elizabeth. As John Henry Newman observed following his famous, but failed, attempt to interpret the Articles in a Catholic sense, “{i}t is notorious that the Articles were drawn up by Protestants, and intended for the establishment of Protestantism.” 12

Article 25, titled “Of the Sacraments,” presents the Anglican assessment of the nature of the seven sacraments traditionally recognized by Catholic Christianity. In a characteristic Anglican compromise, it charts a middle course between the Catholic teaching that all seven are valid and objective means of grace, and the radical Protestant rejection of all sacraments as mere ordinances or customs. While substantially agreeing with the Catholic understanding of the sacramental nature of baptism and the Eucharist, of the remaining Catholic sacraments, Article 25 states:

Those five commonly called Sacraments—that is to say, Confirmation, Penance, Orders, Matrimony, and Extreme Unction—are not to be counted for Sacraments of the Gospel, being such as have grown partly of the corrupt following of the Apostles, partly are states of life allowed in the Scriptures; but yet have not the like nature of Sacraments with Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, for that they have not any visible sign or ceremony ordained of God.

Here the emerging Church of England unmistakably asserted that the ordination of deacons and priests lacks any divinely ordained sign or ceremony, and, thus, does not confer sacramental grace. Apostolicae Curae specifically inquires whether the Anglican Ordinal meets the standard for conveying a sacrament 13 and comes to the same conclusion. The Catholic Church’s imposition of ordination on Anglican clergy converts as if it never occurred before, then, simply recognizes and agrees with the Church of England regarding this central Anglican teaching. Consistent with this recognition, convert Anglican priests also receive confirmation and are re-ordained as deacons. 14

The specific concern of Apostolicae Curae, that the Edwardian Ordinal drafted by Archbishop Cranmer lacked both the form and intent of Catholic ordination, is emphatically confirmed by the content of that rite itself, and contemporaneous expressions of Cranmer’s doctrinal views. Even the most motivated ecumenists have seldom claimed otherwise. “The eating of Christ’s flesh and drinking his blood,” wrote Cranmer in 1550, the year before he revised the Ordinal, “is not to be understood simply and plainly, as the words do properly signify, that we do eat and drink him with our mouths; but it is a figurative speech spiritually to be understood.” 15 Consequently “Christ made no such difference between the priest and the layman that the priest should make oblation and sacrifice of Christ for the layman … but the difference between the priest and the layman in this matter is only in the ministration.” 16

With regard to the crucial question of the nature of the Eucharistic Sacrifice, the Cranmer ordination rite clearly not only did not intend to do, but intended not to do, what the Catholic Church did. The Real Presence was not simply glossed over, it was explicitly rejected. The ministers of the Church of England were intended to be ministers of the Word, by speech in preaching, and by act in symbolic sacraments, and not priests of the true, substantive Body and Blood of Christ.

Historical and theological arguments to the contrary are present in both Anglican and Catholic discourse, but they have failed to carry the day in both communions. There are many theological convictions for which a minority opinion may be the correct one, but on this point, that cannot be the case. Ordination is not a matter of private devotion or opinion, but a public act of the Church. Those Catholics and Anglicans who wish to affirm the Catholic validity of Anglican orders are thus caught in a kind of double bind. Their thinking, no matter how convincing it may be, has not won the agreement of their churches, which, after all, are the ones implementing the ordinations in question. This sociological vise squeezes all who hold such opinions in the two communions, but none more tightly than those Anglicans who hold the most Catholic convictions.

Catholic Conversion and Catholic Orders

Anglo-Catholic disappointment over the Catholic annulment of their orders is especially ironic since it involves the elevation of subjective opinion and experience above the teachings of both churches involved. The implication that the sincerity or personal faith of the ordinand affects the validity of his ordination embodies the very error which Leo XIII contended against on a larger scale. Condemned by Leo’s successor only a decade after Apostolicae Curae as “immanentism,” this view—a central tenet of the errors of Protestantism and modernism—held that “the truth of Christian dogma does not reside in their authoritative formulation, but in the believers’ inner spiritual experience.” 17 Anglo-Catholics have consistently affirmed the broader principle of the objectivity of the sacraments that is expressed in this proscription, commonly with an explicit recognition that a subjective lack of faith does not invalidate a sacrament (though it may impair its effects).

It is only with a certain inconsistency, therefore, that an Anglo-Catholic can appeal to his personal experience of grace, or depth of conviction, or power in ministry, to counter the negative papal judgment on the validity of his ordination. If an objectively sufficient sacrament is valid, even in the face of deficient faith, then an objectively deficient sacrament is still invalid, even in the face of a sufficiency of faith on the part of the recipient. No matter what I may believe about my orders, if the one ordaining (which is the church, not an individual) disagrees, it is the ordainer’s belief that is dispositive, not mine.

Moreover, as the sacrament it affects, the purpose of the ritual of ordination is not to serve the one being ordained, but the community of believers he is being set aside to serve. The objective character imposed on a man by ordination does not become his personal possession which he can carry and use at will. In this respect, Anglican priests who wish to be conditionally ordained, or even only recognized upon becoming Catholic, are similar to Catholic priests who have defected to marry, but still want to function as priests.

Objections to re-ordination by an Anglican priest converting to the Catholic Ordinariate compound this inconsistency even further. It is certainly the case that, in ordaining a priest, the Episcopal Church (for example) has never thought that it was making him or her a Roman Catholic priest. Indeed, most priest converts are inhibited by their bishop for abandoning the communion of ECUSA. Since ordination is by definition not a private, personal affair, but an action of the church, why would anyone expect the Roman Catholic Church, in receiving a convert priest, to confer a status on their Anglican ordination that the Episcopal Church did not intend in the first place?

It is hard to see by what convolution of reason one could feel the necessity for Catholic ordination while simultaneously agreeing with the Episcopal Church, rather than the Catholic Church, about the status of Episcopalian ordination. Surely, someone who recognizes the deficiencies of Anglicanism enough to be led to come into full communion with the Roman Church cannot expect that Church to recognize Anglican orders as a rule. Can anyone blame the Curia for having reservations about the judgment of the Episcopalian bishops in such a matter? Would one advocate that Rome must accede to the validity of the Episcopalian ordination of female priests, or openly gay bishops? By what kind of contradiction can someone privately reject those ordinations, and then turn around and ask the Roman Catholic Church to accept his own ordination established under the exact same ritual and authority?

Perhaps, as an Anglican, one was blessed to be ordained by a Catholic bishop in apostolic succession, who spoke the Catholic words with Catholic intent; but again, perhaps not. How is the Roman Church to decide, in each instance, which Anglican ordinations may be valid (or, technically, licit) and which are not? The Catholic Church has wisely and reasonably chosen to decline to be in the untenable position of making fine distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable ordination practices in the polity and ritual of another church, on grounds that the other church does not itself recognize.

There is another, personal, often unacknowledged, benefit of absolute ordination (and confirmation) for Anglican clergy converts: it makes it utterly clear that the ordinand is converting to the Catholic faith. As the name implies, Anglo-Catholics of a certain disposition believe that they are already Catholic. These emphasize the word “Roman” in “Roman Catholic,” to distinguish themselves as Anglican Catholic, separated from the Roman Church by geography and history, but not by doctrine or liturgy. Priests of this thinking who become Catholic often protest that they did not change; rather, it was ECUSA who defected from the faith and left them. The move to Catholic orders is a mere correction of jurisdiction.

To an Anglican Catholic’s self-image, for such a change to be considered conversion carries a certain degree of offense, implying that they were wrong in believing that they were Catholic. While the Anglo-Catholic claim to catholicity is generally respected as the belief of the holder by Catholic authorities, Apostolicae Curae makes clear that the Catholic Church does not agree with their belief. Despite claims to Catholic identity, including a recognition of papal supremacy on the part of Anglo-Catholics, there is, among many, manifestly an incomplete submission to the judgment of the Roman pontiff on this point. It is, in fact, nothing less than stark self-contradiction to disagree with the Holy Father on the grounds that one has already submitted to him. Those who hold back from becoming Catholic in protest that they are already Catholic demonstrate that they are, in fact, still Protestant.

Despite the many affinities between the two, it is not possible to journey from the Anglican to the Catholic priesthood without conversion. Even—perhaps especially—if the convert priest already agrees propositionally with Catholic teaching, rather than Anglican, where the two are distinct, to become Catholic necessarily involves a new disposition to Church authority. For to be Catholic within Anglican orders involves a certain opposition to the teaching and ethos of one’s own church; to leave that church ineluctably involves a rejection of its authority. The authority may be mild and generously imposed; its rejection may be reluctant, regretful, and enacted with deep respect; yet the authority is imposed and it is rejected. Examining and opposing the precepts of one’s own faith may have been a conscientious strategy of survival; one’s very soul may have been at stake. But to enter the harbor of Peter means just precisely to lay aside all such opposition from now on. To become Catholic, as a priest, means to submit one’s private insight and judgment to the collective wisdom of the Church. We must accept the Church as our mother, not our handmaid. Leaving one’s own faith for cause is an essentially Protestant act. But just as leaving Anglicanism may be their last Protestant act, so joining Rome must be the first Catholic one.

Authority and Efficacy

As with many other issues, the intellectual debate over the validity of orders reflects, among Anglican priests considering conversion, a concern for the legitimacy of the ministry they have known and exercised for much of their lives. For those who may understandably feel otherwise, therefore, it is important to state clearly that absolute ordination in no way involves a detraction of Anglican priesthood. From a Catholic perspective, the question of the formal validity of Anglican orders is not a question about the efficacy of Anglican ministry. While Apostolicae Curae holds that Anglican ordination does not confer the fullness of Catholic orders, this by no means implies that Anglican ordination is without its own value and purpose.

The Catholic Church today views the relation of Catholic to Protestant, not as the difference between wrong and right, but as between part and whole. It recognizes that many elements of genuine sanctity, doctrine, and orders are to be found in the separated churches of the Reformation, among whom, moreover, Anglicanism is held to have a special place. The bishops of England and Wales, in a joint statement, have made this explicit: “We would never suggest that those now seeking full communion with the Roman Catholic Church deny the value of their previous ministry. According to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council, the liturgical actions of their ministry can most certainly engender a life of grace, for they come from Christ and lead back to him and belong by right to the one church of Christ.” 18

If one’s personal experience of grace in Anglican priestly ministry does not prove that the underlying orders are valid, it is equally true that a defect in the underlying orders does not nullify the experience of grace. Consider the case of an annulled marriage. Here, in analogy to Apostolicae Curae, the Catholic Church judges that a defect in form and/or intent in the marriage ceremony renders the marriage thus initiated to be sacramentally null and void. This judgment, however, in no way denies that a genuine relationship existed between the couple, that the spouses may truly have loved and been a source of grace and blessing to each other. Just as the personal experience of the spouses does not, by itself, legitimate the marriage, so the sacramental nullity of the marriage does not, by itself, deface their experience of love and life in their relationship. The lives of their children, if they have them, are recognized with joy and thanksgiving, and their legitimacy is, in no way, impaired by the annulment.

Imagine further, the case of a couple who discovered, after years of happy marriage, that there had been some legal (or canonical) defect in their wedding license and that they were not legally (or canonically) married at all. To continue their marriage, such a couple would have to get married again, absolutely, in recognition that their former ceremony was null and void. Would that absolute remarriage negate the relationship they had developed? Would the love they had shared prior to this discovery be made null? No. The reality of their experience, the very real union of their lives and bodies, would not be negated in the slightest by the defect in their authorization. In the same way, Apostolicae Curae’s declaration of nullity of Anglican orders in no way denies the genuine grace and truth that is present in Anglican ordained ministry. The Catholic Church recognizes with joy and thanksgiving, and affirms the legitimacy of, the fruits of the Anglican priesthood.

The problem with Protestantism, as I’ve said, is not that it has none of the truth, but that it has only part of the truth. A Catholic Anglican, we might go so far as to say, has almost all of the truth. But almost all is not all, and if he wishes to be whole, he must recognize that his orders cannot be patched, but must be redone from scratch. If Anglican orders are not complete, they are, nonetheless, something, even much; and what they are is good, laudable, and worthy of affirmation and thanksgiving. Just as John Henry Newman, after reconciling with Rome, still valued and appreciated the strengths of Anglicanism in his day, the Roman Catholic Church, while recognizing the need for it to be completed by a fuller communion with Rome, values and appreciates the ministry of Anglican priests, and strongly affirms the prior ministry of its former Anglican priests.

For this reason, the following prayer, written by Cardinal Hume and approved by the CDF, has been recommended for inclusion in the Roman Catholic ordination of a former Anglican priest since 1998:

Oratio ad gratias agendas pro ministerio ab electo in Communione anglicana expleto

(Prayer for giving thanks for the former ministry of the ordinand in the Anglican Communion)

Deinde omnes surgunt. Episcopus, deposita mitra, stans manibus iunctis, versus ad electrum, dicit:

(Then all rise. The bishop, having doffed his mitre, standing with joined hands, facing toward the ordinand, says:)

N., the Holy Catholic Church recognizes that not a few of the sacred actions of the Christian religion as carried out in communities separated from her can truly engender a life of grace and can rightly be described as providing access to the community of salvation. And so we now pray.

Et omnes, per aliquod temporis spatium, silentio orant. Deinde, manus extensis, Episcopus orat, dicens:

(And all, for a certain space of time, in silence pray. Then, with extended hands, the Bishop prays, saying:)

Almighty Father, we give you thanks for the X years of faithful ministry of your servant N. in the Anglican Communion (vel: in the Church of England), whose fruitfulness for salvation has been derived from the very fullness of grace and truth entrusted to the Catholic Church. As your servant has been received into full communion and now seeks to be ordained to the presbyterate in the Catholic Church, we beseech you to bring to fruition that for which we now pray. Through Jesus Christ, our Lord.

Populus acclamat:

(The people acclaim:)

Amen.

- National surveys of priests in 1993 and 2001 found that 70.3% and 71.8% respectively agreed strongly or somewhat with the cited statement. The surveys were administered by the Los Angeles Times; the data are archived at www.thearda.com. ↩

- Jon Nilson, “A Roman Catholic Response {to the Centennial of Apostolicae Curae},” Anglican Theological Review 78, no. 1 (December 1, 1996): 122. ↩

- First Anglican/Roman Catholic International Commission, “Ministry and Elucidation,” 1979, sec. 6, http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/angl-comm-docs/rc_pc_chrstuni_doc_1979_ministry-elucidation_en.html. ↩

- Giles Pinnock, “Anglicanorum Coetibus & Apostolicae Curae,” Onetimothyfour, November 12, 2009, http://onetimothyfour.blogspot.com/2009/11/anglicanorum-coetibus-apostolicae-curae.html . ↩

- Callan Slipper, “The Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus of Pope Benedict XVI from an Anglican Perspective.,” Ecumenical Review Sibiu / Revista Ecumenica Sibiu 2, no. 3 (November 2010): 178–9, doi:Article. ↩

- Ibid. However Slipper also argues that reordination is a relatively minor concession compared to others required in the Ordinariate. Here and throughout, for simplicity, “the Ordinariate” refers to both the English and American ordinariates formed to receive former Anglicans into the Catholic Church. ↩

- R. David Cox, Priesthood in a New Millennium: Toward an Understanding of Anglican Presbyterate in the Twenty-First Century (Church Publishing, Inc., 2004), 416. ↩

- Anglican Communion News Service, Release #2219, “Statement by the Archbishop of Canterbury Concerning the Roman Catholic Document ‘Dominus Iesus’,” September 5, 2000, http://www.anglicancommunion.org/acns/news.cfm/2000/9/5/ACNS2219 . ↩

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Doctrinal Commentary on the Concluding Formula of the Professio Fidei,” L’Osservatore Romano English Edition, July 15, 1998. ↩

- Andrew Burnham, “The Centenary of APOSTOLICAE CURAE: A Simultaneous Process of Convergence and Divergence,” New Directions 15 (August 1996), http://trushare.com/15AUG96/AU96APOS.htm , writing well before Dominus Iesus, discusses additional factors leading to the disappointment of Anglican hopes for consensus on the question of orders. ↩

- Technically, Apostolicae Curae holds that Anglican Orders were definitively declared invalid in 1704 by Clement XI. Leo XIII, Apostolicae Curae, {On the Invalidity of Anglican Orders}, 1896, sec. 20. ↩

- John Henry Newman, Tract 90 (John Henry and James Parker (1865), 1841), 83. ↩

- Leo XIII, Apostolicae Curae, sec. 24. ↩

- Norman Doe, “The Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus: An Anglican Juridical Perspective.” Ecclesiastical Law Journal 12, no. 3 (September 2010): 313, doi:Article. ↩

- T. Cranmer, Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament (1550) (Focus Christian Ministries Trust, 1987), 135, http://books.google.com/books?id=cpKAHAAACAAJ. ↩

- Ibid., 246. Gregory Dix’s argument that the Edwardian ordinal should not be interpreted according to the “private sense” in which Cranmer understood it ignores the facts both that Cranmer, as the Archbishop of Canterbury, acted with the authorization of the church in revising it and that Cranmer’s view was subsequently officially codified in the Thirty-Nine Articles; see Gregory Dix, The Question of Anglican Orders (London: Morehouse-Gorham, 1956). ↩

- George H. Tavard, “Apostolicae Curae and the Snares of Tradition,” Anglican Theological Review 78, no. 1 (Wint 1996): 46. ↩

- Statement of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales, November 18, 1993, cited in ibid. ↩

As an ANGLICAN / CATHOLIC priest I certainly do not have any problem being ordained as a catholic priest within the ORDINARIATE, I regard it as a positive step, and another source of great grace. PRAISE THE LORD. FR. BILL H.

Great article!

The problem is that RCs misunderstand the function of the XXXIX Articles. They’re not a catechism. They’re a setting of boundaries within which Anglican clergy were expected to stay. They are, on the whole, purposefully ambiguous; hence, XXV can be read either as denying that the 5 “lesser sacraments” are sacraments at all, or as merely demoting them to a lower status than the two dominical sacraments. RCs who want clear and unambiguous declarations of doctrine will not be mollified, of course–but in any case I had thought that Apostolicae Curae concentrated mostly on the language of the Ordinal and found it defective (why, I don’t know, since the current RC Ordinal uses nearly identical language). Oh well–most trad Anglicans aren’t losing any sleep over it at any rate.

I crossed the Tiber and is one the best moves I have ever made. I am a former Episcopalian who’s time and formation I am grateful for. Even though I was raised in a low church environment the truth of the Catholic Church was there and the historical issues were part of me. During my upbringing I taught there were seven sacraments, the priest we had was an Anglo Catholic assigned to a low Church. I believed in the real presence in the Eucharist. The foundation led me into a Catholic direction. My Episcopal Confirmation will always mean something to me. The day after I crossed the Tiber I told Monsignor Steenson who re-confirmed not to throw away my old but walk with a fullness. In an old 1928 Book of Common Prayer the signatures of Bishop Gray Temple & Monsignor Jeffery Steenson signatures lay side by side. Mongr Steenson wrote a note in the prayer book “Reception & Confirmation into the Catholic Church, the rock from which we were hewn.” This Prayer Book to me a symbol that we will all be one. We are not there yet but what a start. Becoming Catholic in the Ordinariate is just that I am not absorbed because my past but became my fullness in faith. The Ordinariate is just a beginning it slowly grow as well as evangelical Anglicans that severed ties with the Prostestant Episcopal Church USA. That faith left me and Rome where I had to go. But the Evangelicals I shared many of the same reasons for leaving and have a few friends who stayed. They are all brothers and sisters and respect each and everyone journey but the Ordinarate gave me a fullness of faith on the Rock of St. Peter which is where we never should have left. I was not born and did not have a choice when Henry VIII tore a strong Catholic Church from its moorings. As Monsignor Steenson stated on the Journey Home. “Henry Tudor you did not win.”

Fr Sullins, you write, that “Queen Elizabeth I, in 1570, declared the Catholic view of orders deficient from an Anglican perspective.” Could you please provide me with a documentary reference for this? I have no doubt that it is true, but had never heard of it before and the lack of a citation has been noted in an exchange in another place. I would like to be able to provide it.

I am a former Anglican priest, now Catholic and aspiring to ordination through the Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter. As such, I found your article a very useful exposition of the matter in question. While at one time I would have expressed reservations about “reordination,” I found that as I came to the point of deciding to stop rehearsing and start practicing the Catholic faith by entering the Catholic Church, those reservations had evaporated. It comes, I suppose, from accepting that the Church knows better than I do as to what she should require of her ministers, and therefore I will gladly and gratefully comply, should she call me to holy orders.

This is an interesting article, though I find its conclusions lacking and have been convinced otherwise. I’m a former Roman Catholic theologian who was recently received into the Episcopal Church in order to respond to a lifelong vocation to the priesthood denied to me by the Roman Church for no other reason except my 25-year marriage. I believe the Anglican Ordinariate is a step toward the eventual recognition of Anglican Orders by the Roman Magisterium. My own theological studies brought me to that conclusion long ago.