The Gospel summons us to authentic human development in communion, community, and communication under the sovereignty of God’s love. Our Christian conversion is both an event and a lifelong process of ongoing response to the grace and call of the God of all humankind.

All life at any level is a matter of communication; what we think of as a low level of life involves a low level of communication, but every organism is an organism in virtue of its power of communication. Human life is constituted by an especially high level of communication, the kind we call language. What makes a human body human is that it is involved in linguistic communication. That body is a source of communication. All human media of communication are extensions of the body. The human body extends itself into language, into social structures, into all the various and complex means of living together that human beings have created. We should not see human bodies as atomic units externally linked by media of communications; to be human is to be in communication, a common language of interweaving extensions of the human body. The implication of this is that we have a task of becoming human. Humanity in its completeness is not something that we altogether receive; it is something that we are summoned to achieve.

The Gospel summons us to authentic human development in communion, community, and communication under the sovereignty of God’s love. Our Christian conversion is both an event and a lifelong process of ongoing response to the grace and call of the God of all humankind. Jesus Christ, as the suffering Messiah, reveals this God to be in the service of all in establishing communion, community, and friendship among all and between them and God. Christian conversion has a universalist and communitarian dimension inasmuch as it entails transformation in every sphere of human life.

The self-surrender to God of those who adhere to Jesus Christ and his way of costly and generous self-giving service is a transforming and integrating participation in the freedom and power of God’s pouring out his life for all. Jesus Christ reveals the community-creating and community-sustaining God pouring out his life for all, in and through his new covenant community. Christian conversion occurs wherever we are becoming new covenant persons, giving our lives in the Spirit of Jesus and his Father for others in every sphere of human life and endeavor. Christian conversion, represented by Jesus Christ’s way of the cross, is a lifelong process of self-transcending love: the only way for the achievement of authentic human development and integration for all human persons.

We are not by nature participants in the divine nature or in the inner life of God; however, through the free gift of God’s love flooding our hearts through the Spirit given to us (2 Pt 1:4 and Rom 5:5) the Jesus story/life is ours, his freedom and power to love God above all and to do good for selfless reasons is ours. His freedom or power to forgive, to reconcile, to trust, and love is ours, transforming us from being selfish persons to becoming selfless persons in communion with our self-giving God pouring out his life for all.

There are endless ways in which we become integrated into the life/love of the triune communion or Blessed Trinity—ways in which the Jesus story/life becomes ours, enabling us to become our true selves, together-with-all-others under the sovereignty of God’s love. As Christians, our spiritual quest for communion begins with the Good News that God has established, in Jesus Christ, his eschatological banquet community for all humankind, enabling us to find or become our true selves in communion. God’s self-investment in human life enables and calls for our transformation in the triune communion of the banquet community. Such transformation/conversion entails overcoming our destructive tendency to self-idolatry, to loving and serving ourselves above all divine and human others.

The community of Christian faith welcomes Jesus Christ as God’s Good News for all humankind, recognizing that to be with him, and all others in the triune communion, is the fullness of life or destiny of every human person. The Triune God creates and sustains every human person for that eternal communion.

By drawing everyone into his humanity and sonship, Jesus inaugurates a new community, the Church, which is his body and the enduring sacrament of the Father’s love for the integration of all humankind in the life/love of the sacred Trinity. Our ongoing Christian conversion (metanoia) means our learning, in the Spirit of Christ, to become self-bestowing persons (kenosis), serving others (diakonia), for the fullness of life in the triune communion (koinonia).

We are constantly besieged with new theories of justice, massive legislation and legislative proposals, arms treaties, and rhetorical symbols. These are good and worthy human efforts. But they will not by themselves solve our “social problems.” Nor will a new view of the Trinity. But we must continually recall that both our human family and our personal worth have a transcendent model and value, the only one that makes human efforts fully worthwhile. And to assure such recollection, there must be in the world a community in which Jesus dwells with his Father and Spirit, a steady reminder, a sacrament, of the communion and friendship to which all are called by the Trinity. It is this community that enlightens our search for our true/real self, for authentic human development and integration, affirming that it is achievable only through a self-transcending love that pulls us out of our isolated self-concern, and into communion with all men and women with our Triune God.

The Trinity: Communion of Divine Persons

The Trinity is, indeed, a mystery, a secret, but one that has been revealed in Jesus, the Son sent by the Father and, with him, sending the Spirit into the world. Our Christian creeds, our Christian commitment, are structured around this mystery. From the beginning, apostles, missionaries, bishops, Christian philosophers and theologians have searched, probed, and struggled to unfold the meaning, and maintain the integrity, of this central message. For all reflective Christians, it has been the inspiration for both thought and devotion.

With a journey through Scriptures, St. Irenaeus of Lyons searched into this mystery with a loving and a questioning heart. He allegorically calls the Son and the Holy Spirit the “hands of God” (Adversus Haereses 5,1,3; 5,5,1; 5, 28). Irenaeus believes that the Father is always at work in human history, shaping humankind into the image and likeness of the triune communion of the three divine Persons, because the words, “Let us make humankind into our own image and likeness,” are addressed by the Father to the Son and the Holy Spirit. The Father creates, embraces, and draws all humankind to himself through his Son and Spirit. He draws all humankind with his two “hands” into the heart of the triune communion.

By creation and redemption, the Father, with the Son and the Spirit, initiates and consummates this search. The Trinitarian community is the source, model, and goal of our communion with one another, and with God. This is the model that Jesus from the cross set up between Mary, his mother, and John, the beloved disciple. In and through them, this was to be the model of the Church, and the call to all people.

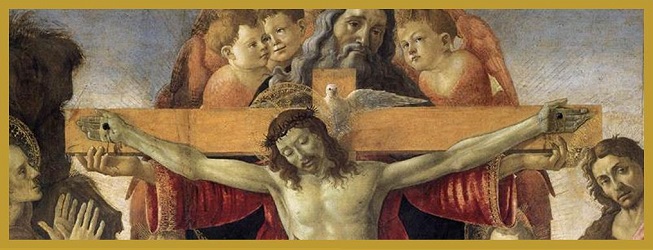

The body of Christ is the icon of the Triune God in John’s account of Mary and John at the foot of the cross (19:25-30). The crucified Christ incorporates his mother and beloved disciple into his life by giving them his Spirit (19:30). The Father lives in Jesus (14:10). Jesus can give that life, the Holy Spirit of the Father (14:16; 15:26), because he possesses it. As the Father loves the Son, the Son loves the disciples (15:9). The Holy Spirit, the life and love of the Father and Son, is the gift of the Father and Son to Mary and John, the beloved disciple, enabling them to fulfill the demand/call of the Father and Son to remain in their love (15:9, 12, 17). The Father loves them for loving his Son (16:27) because his Holy Spirit lives/loves in them. Through the gift of the Holy Spirit of the Father, they are in communion with the Father in loving the Son. The Holy Spirit is equally the gift of the Son, through whom they are in communion with the Son in loving the Father.

The farewell discourse at the Last Supper not only discloses the eternal life and love relationship of the Father and the Son, but also the divine demand/call that we enter into that relationship. Jesus promises us that the Spirit of that eternal life and love will dwell with us forever (14:16-17, 25-26; 16:7-15), or, in still fuller words, the Trinity will draw us into its triune communion through the efficacy of his self-giving death and resurrection (14:23). From the moment when God pitched his tent in the camp of his people (1:14), to the great vision of the Apocalypse (21:1-4), John’s Good News is that God dwells among us as the ultimate fulfillment of all human life. The triune community of the divine love/life, we already know from 13:35, is manifest and communicated in the loving reciprocity of the disciples/body of Christ. Our living in the Holy Spirit of the triune love/life fulfills the demand/call for reciprocity (15:17), that both the Father and Son enable us to fulfill through their self-communication in the gift of their Holy Spirit. The Father and Son come to us and dwell among us in their Holy Spirit, creating and sustaining the community, or body of Christ, as the icon of their triune love/life for all humankind.

The triune communion is shared with all humankind in the Father’s missioning of his Son and Holy Spirit to unite all humankind in communion, community, and communication with, and through, the koinonia of the Son with the Father and the Spirit, and the koinonia that the Incarnate Son is with God and humankind. The Triune God is a koinonia of the three Persons. The Incarnate Son is the koinonia of the Triune God with humankind. He is the only divine person with a human mother, and the only human being with a divine Father. His distinctness and uniqueness does not separate him from divine and human others; rather, it is his distinctiveness and uniqueness that he shares in communion with divine and human others.

We have a tendency, in our modern era, to think of a “person” as an autonomous entity, an independent seat of consciousness, which has no necessary relations or dependencies on anyone or anything else. This was not the view that St. Augustine had in mind when he advocated the use of the word “persona” to speak of the Three. But the modern emphases on infinite freedom—understood as a lack of restraint—and on autonomy—defined as throwing off one’s “tutelage” by others—have led to a highly individualistic notion of personhood (See David S. Cunningham, “The Trinity,” in The Cambridge Companion to Postmodern Theology, Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Ed., Cambridge U. Press: Cambridge, 2003, pp. 197-199).

The Scriptural Iconography of John’s Gospel

In the scriptural iconography of John’s Gospel, we “see” the Triune God in the body of his crucified Son pouring out his love/life for all humankind. When the crucified Son bows his head and gives up his spirit (19:30), we “see” the Father and the Son (14:9) giving us their Holy Spirit, sharing the love/life of the triune communion with all humankind, enabling us to have, in their eternal communion, a relationship with one another that death itself cannot destroy. The eternal communion of the Father and Son is both seen and communicated in the crucified body of Christ that draws Mary and John together in the reciprocity of mother and son. The Father, who eternally pours himself out in selfless, self-giving love, is seen in the icon of the Triune God, in the human self-giving love of his Son, pouring out their Holy Spirit to draw all humankind together within the loving reciprocity of the triune communion. The Son, who eternally welcomes the selfless, self-giving love/life of his Father, is “seen” in the icon of those who welcome that same love/life that the Holy Spirit of the triune communion recognized in the mutual love of the disciples (13:35). The Holy Spirit of the Father and Son is “seen” by the eye of faith in the self-giving and welcoming love that forms the body of Christ and temple of his Spirit—the icon of the triune communion.

Jesus Christ expresses and communicates the grace and demand, the gift and call, of the Triune God for life within the triune communion. He is the icon of the God who both gives his love, and calls for reciprocity in communion. If God is love, that love has its imperatives or commandments (e.g. 14:15, 21; 15:10, 12, 17). Jesus commands his disciples to love one another (15:17); he tells his mother to make John, the beloved disciple, her son; he tells his disciple to make Mary his mother. He enables them to meet the demands of God’s love by giving them his love/life as the members of his body and the heirs of his Spirit.

As members of the body of Christ, Mary and John are central figures in John’s scriptural iconography of the Triune God, the communion, community, and communication of Father, Son, and Spirit. To see the son commending his mother and beloved disciple to one another, and giving up his spirit, is to see the Father offering all humankind life in the triune communion through/in the body and Spirit of his Son. The Son’s love for his heavenly Father and human mother integrates humankind within the life of the triune communion. The love that proceeds from the Father is the Son’s love for both his Father and human mother/humankind.

The Greatest Act of Love: Two Perspectives

The ultimate meaning and fulfillment of Mary’s maternity is revealed in the birth of the new family of God. Jesus shares with all humankind the life/love that he receives from his heavenly Father and human mother, making good his promise that when he was lifted up on the cross, he would draw everyone to himself (12:32). The interpersonal life of Jesus Christ integrates/unifies humankind with the Triune God in the triune communion. He communicates the life/love/Holy Spirit of the triune communion through, and in, his divine filial relationship with his Father, and his human filial relationship with his mother. He is the integration of the Triune God and humankind that he enables and demands/calls for. With filial love, he welcomes the divine life of his Father and the human life of his mother, and he pours out that life for the ultimate fulfillment of all human life in the triune communion. Every beloved disciple is called to welcome that same life, and share it with others, just as Jesus welcomes and shares it. Our incorporation into the life of Christ gives us a direct share in his mission. Communion with God, through and in Christ in the Holy Spirit, makes us sharers in the life of each other, in the communion of the saints, a communion that transcends death itself.

John interprets the death of Jesus as the climax and culmination of his life: “Greater love than this no man has, than that he lay down his life for his friends” (15:17). By interpreting his self-giving death as the culmination of his life, John is saying that, in his death, Jesus was most alive, that Jesus was most alive in the giving of his life. The crucified Christ for John is not an icon of death, but of life even in death. John can assert this paradox of life and death from two perspectives. First, in giving his life, Jesus gave not this or that part of himself, but his whole self, his whole interpersonal life, with both his divine Father and human mother. There was nothing more that he could give. Laying down the fullness of his divine and human life, in the triune communion for his friends, is the greatest act of giving, the greatest act of divine and human love.

But it is also the greatest act of love from a second perspective. Jesus gives the fullness of his interpersonal life in the most complete and final way. From both perspectives, John can interpret the death of Jesus as the climax and culmination of his life, as the moment when he was most alive. Loving his own unto the end (13:1) means not just to the final moment, but to the very limits of which love is capable. For John, then, Jesus was not passive in his dying, and his death was not just something inflicted on him. As seen by John, Jesus, in his death as an act of self-giving, reached that moment in his life when he was most active, most personal, most free. The death of Jesus was an act of living/loving, not an act of dying. It was an affirmation of life in the triune communion even in the face of death. This theme is at work in John’s story of the Good Shepherd, who lays down his life for his sheep “that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (10:11). This is a clear allusion to, and interpretation of, the death of Jesus as the fullness of his community-creating, and community-sustaining, self-giving love for all others.

The communion of the Christian community reveals, and communicates, the Holy Spirit of the self-giving Father, and his self-giving Son, integrating humankind within the communion, community, and communications of the Triune God. Christ crucified is the icon of the loving outpouring of diving and human life in reciprocity that constitutes such communion (koinonia).

He is the icon of the divine and human selflessness in communion with all divine and human others, willingly paying the price that such communion entails; for there can be no communion (koinonia) without selfless self-giving (kenosis). Death itself cannot quench the invincible Spirit of love that is the eternal life of the Father and Son in the triune communion. The Spirit is always a gift, the Triune God’s self-gift and call to our true/real selves in the fullness of divine and human life, together will all others, enabling us to do and to become what would otherwise be humanly impossible. Because God alone fully loves all others, good and evil, only the gift of the Spirit enables us to love all others with the same love that no human evil or death itself can quench.

Welcoming the Holy Spirit Is Not Passive

Our receiving the Holy Spirit of the Triune God is not passive. The mother and faithful disciple stand by the crucified Christ, actively welcoming his love commandment, and the gift of his enabling Spirit. We are never more fully alive and intensely active than when we love God with all our heart and mind and soul and all others as ourselves within the triune communion enabling such love. The Christian community—the body of Christ and the temple of his Spirit—is the living icon of the Triune God when it stands faithfully by its crucified Lord, actively welcoming the gift of his Spirit in obedience to his call to the fullness of life within the triune communion. The gift of the Spirit enables the Christian community to follow its crucified and risen Lord’s way of the cross: the way of selfless, self-giving love that culminates in the resurrection of the just, for the fullness of life in the kingdom of the Triune God. Our ongoing Christian conversion (metanoia) means our learning in the Spirit of Christ to become a self-bestowing person (kenosis), serving others (diakonia) for the fullness of life in the triune communion (koinonia).

God Speaks in Living Icons of Hope and Love

God speaks his word of hope and love in living icons, images, or efficacious signs (“sacraments”) that move our hearts and enlighten our minds. We cannot do what we cannot, at least in some way, imagine. We cannot believe, hope, and love—our most significant “doing”—without enabling icons. We cannot perform the deeds of faith and hope and love without living icons or images that orient us to decision and action. The Eternal Word became flesh in the perfect image or icon of God that is Jesus Christ, in order to transform all human hearts and minds, enabling us through the gift of his Spirit to love and hope in God above all, and our neighbor as ourselves. Jesus Christ and his body (the Church) are the effectively transforming icon of God’s creative, sustaining, and predestining love for humankind, enabling our responding love and faith and hope. The Christian community affirms that it has seen or experienced the “glory” of God in his perfect image (icon), Jesus Christ; for “glory” is the impact of God’s active presence, transforming our lives. God’s glory is manifest wherever his will is done, or his love communicated, wherever we experience the transforming impact of his goodness.

The beauty of God’s perfect image (icon) in Jesus Christ, according to the Greek Fathers, redeemed us by the impact of its powerfully transforming beauty, drawing us away from all moral and spiritual ugliness by attracting us to the Father. We are drawn to the fullness of life in God by the powerfully attractiveness/beauty of the living icons who concretely manifest his true goodness. The friends of God are the manifestations of his beauty, the glory or impact of God in human life stories. They are the living icons in which God, in love, transcends even his transcendence through his real presence and activity in time and space; their true goodness, or “godliness,” attracts us to God in faith and hope and love. We experience the goodness, trustworthiness, and credibility of God in, and through, the beauty of his living icons. We “know” God, in the biblical sense of personally experiencing his goodness, in our true love for one another; we know the Spirit of the Father and the Son in such love, enabling us to affirm that God is love.

As living icons of hope and love, we share Jesus Christ’s transforming and redemptive life; for images are orientations to decision and action. Our heroes, models, saints, and leaders are our images of what we should be like. The images we have of ourselves, others, and God shape our lives. It is important that these images be true, for they determine how we think and feel and act in our basic relationships with ourselves, others, and God. Living icons of hope and love are a work of hope and love for others, who may well envision themselves as no more than particles of dust lost in a meaningless void.

The Church’s Scriptural Iconography

The Church’s scriptural iconography serves as a matrix for the development of Christian life at every level: intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, national, and international. It is employed to foster prayerful contemplation and meditation, critical theological reflection, moral responsibility, and social commitment. The Church employs it to free us from false and distorted images of ourselves and God, that orientate us to self-destructive behavior. Christ redeems our images. The Church, as the body of Christ and the temple of his Spirit, transforms our lives by transforming our images through its scriptural iconography. Our prayerful reading and study of Scripture grounds our communion with Christ and his Body, orienting us to follow his way of total self-surrender to God in the service of others, transforming us into living icons of hope and love for all.

Jesus Christ: Divine and Human Communion

Jesus Christ is the living embodiment of the Good News of divine and human communion, the sign of the kingdom, manifesting what human beings are like when they come under the rule of God. Similarly, his body, the Church, is the living embodiment of the Good News, the sign of the kingdom, of God’s new society manifesting, however imperfectly, what the human community is like when it comes under the rule of God. The Good News of God’s purpose for all humankind is manifested and proclaimed in Jesus Christ and his body, the Church, where the Word of God becomes visible, and the image of God becomes audible. God has manifested and proclaimed himself by sending his only Son: “No one has seen God, but God the only Son … has made him known” (John 1:18). So Jesus could say: “He who has seen me has seen the Father” (Jn 14:9); and Paul could add that Jesus is “the image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15). Similarly, the invisible God, who made himself visible in Jesus Christ, continues to manifest himself in Christians when they love one another: “ No one has ever seen God, but if we love each other, God lives in us and his love is made perfect in us” (1 Jn 4:12). To the extent that the loving communion, community, and communication of the body of Christ visibly and audibly substantiates the credibility of his good news for all, it opens the eyes of the blind, and unstops the ears of the deaf ,for the transformation of all humankind into a truthful and loving community.

Christian Conversion

Divine and human communion, community, and communication is the aim, or outcome, of religious and Christian conversion in response to the transforming love that the Spirit of God has poured into our hearts (Rom 5:5). The eye of love that is faith, and the gaze of love that is Christian contemplation, are fruits of the Spirit’s love poured into our hearts. The gift of the Spirit gives us the eyes to see, and the ears to hear God’s love for us, in Jesus Christ and in all creation. The First Commandment expresses the imperative of that Love which enables and calls for our communion, community, and communication with God and all others. It calls for our radical openness to, and complete dependence on, God, challenging the culture of the imperial autonomous self, and any view of life which regards the human ego as ultimate reality.

Peace or Shalom or Justice—the dynamic state of right relations in our relational life—is the end result of the human response to the grace/gift and call/demand of Love/Wisdom/God. In Johannine terms, this is the “fullness of life” which the grace/gift and call of Christ communicates to those who welcome it

Lonergan’s theology of religious and Christian conversion finds biblical equivalents in the themes of metanoia (personal transformation), kenosis (self-giving generosity), diakonia (service), and koinoia (divine and human friendship).

Metanoia implies a transformation of the subject from being the narcissistic center of his world, to recognizing and accepting the fullness of his true life as a being-together-with-all-others-under-the-sovereignty-of-God’s-love in a created universe, as a distinctive part of the whole/fullness. This focus is on the subject of conversion: the integrating center of cognitive-affective consciousness.

Kenosis implies that the transformation enables one to become a self-giving, sharing, generous, and hospitable person, welcoming and sustaining others. This focus is on the subject as an agent interacting responsibly with others. The radical gift of the self testifies to the truth that self-giving, not self-assertion, is the path to goodness and flourishing in the human community.

Diakonia implies that our self-giving is a genuine service for the good of others, rather than a form a self-service (self-promotion, self-glorification).

Koinonia implies that the first three moments of conversion culminate in a communion, community, and communication with others in shalom, peace, the fullness of life under God. This aspect’s focus is on the outcome, or result, of the first three moments: the body of Christ and the temple of his Spirit, the church, and the coming of the kingdom of God’s rule/Spirit. In other words, there is no authentic communion, community, and communication without the first three moments of human transformation.

Peace and Civic Friendship

Communion-community-communications is the dynamic of peace and civic friendship. Peace is not primarily the absence of war; rather, it is the achievement of civic friendship.

Peace, as communion-community-communications, is the modus operandi of knowing and loving subjects who are responsible agents in both their decision and action within all the contexts of their relational life.

The quality of the human subject, as an integrating center of cognitive and affective consciousness, preconditions the decision and action of that subject as an agent, so that true vision is the sine qua non for intelligent, reasonable, and responsible decision and action.

The human subject has a conscious and affective awareness of various contexts of its relational life: the intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, national, international, and ecological. As Christians, we believe that we encounter the grace/gift and call/demand of God for responsible decision and action within each of these many contexts. To the extent that we respond responsibly to the grace and call of God within them, we shall enjoy the peace of God within them: we shall be at peace in ourselves, others, the world, and God. Conversely, to the extent that we are our own little gods, or irresponsible, we shall be in a perpetual state of civil war, clamoring to control and exploit others for our own self-interest, as opposed to our common good. (God is the Common Good of the universe; so, letting God be God in accordance with the first commandment, is indispensable for peace within all the contexts of our relational life, within our basic self-others-world-God relation.

Aristotle’s Politics recognized that true vision was indispensable for authentically reasonable and responsible (just) action. As Christians, we can agree with Aristotle in theory; however, given the fact of original sin, we recognize that the achievement of a lasting peace depends on human fidelity to the grace/gift and call/demand of God. There will always be need among individuals and societies for a forgiveness, pardon, and reconciliation that God alone can give. As Herbert Butterfield has concluded in his Christian philosophy of history: in almost every century, the human race seems to have come close to total self-destruction; the fact that it has been spared the logical consequences of its self-destructive decisions and actions would seem to confirm the Christian belief in a divine providence.

William F. Lynch, in his Images of Faith, says that all human beings are born with a basic faith in others. In fact, faith always comes before knowledge or proof. We take things on the word of our parents, friends, and teachers before we can ever substantiate them for ourselves scientifically. Where there is no faith, there is no future. Lynch says that, from the start, we seek persons who can educate our basic faith: heroes, models, saints, leaders. The problem is to find the right educators and models. Persons with a Christian faith have chosen Jesus Christ to be the educator of their basic faith, their working hypothesis for life within all their relational contexts. We believe that he reveals what is authentically human and authentically divine. The founders of all religions have been chosen by their followers as the educators of their basic faith about the relationship of the divine and human. There are many subordinate educators of that faith. There is always the danger that those we have chosen can betray our basic faith with dire consequences. All human communion, community, and communication is conditioned by those whom we have chosen to educate our basic faith. (Wittgenstein: “If you cannot give one concrete example of what you are talking about, perhaps, you just do not know what you are talking about.” We point to the educators of our basic faith to know what we are talking about.)

There can be no communion, community, and communication (Shalom, peace, justice in the full biblical sense) without hope, confidence, trust, reliance on the goodness of others, human or divine. Christians believe that, ultimately, God alone is good. In other words, Ultimate Reality is trustworthy, reliable, meaningful, and benign.

Because we are social beings, all human development and maturity depends on the active goodness, compassion, reliability, help, and collaboration of others. We are not self-made individuals; rather, we are born into a network of others—divine and human—through whom we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28). We cannot live without counting on the divine and human others who are there for us.

Three Complementary Aspects of Church Leadership Promoting Communion

The new creation that is Jesus Christ—and his body, the Church—is the fruit of the Spirit of the Triune God’s communion, community, and communication with humankind. The Incarnation and the birth of the Church at Pentecost are the fruit of the unifying Spirit.

The Spirit of the Triune God creates, unifies, and leads the Church through its members in three major forms of Christian leadership: institutional, charismatic, and intellectual; or, in other terms, structure, spirit, and theology—the kingly, the priestly, and the prophetic dimensions.

The Church needs structure and order if it is to survive; it needs ardor, zeal, and heart, if it is not to become a prison of the Spirit: it needs intellectual rigor and commitment to the truth if it is to have a Gospel to preach. A Church in which one of these elements dominated or was unchallenged by the others would be rule-bound, or in retreat from ordinary life, or with no truth to proclaim.

Institutional Leadership

The papacy is the means of anchoring movements within the church, not their initiator or inspirer: the spiritual and intellectual leadership of the Church in the age of Innocent III, for example, lay in Assisi and Toulouse, and in the University of Paris, not in Rome. The pope’s role has historically been that of an anchor, not a pioneer or trailblazer. Inventive leadership—the sort of originality of spirit or intellect which leads to breakthrough or a rank shift in the way Christians view the gospel and the world—rarely comes from the Church’s officers, but is usually the result of a charism, which, indeed, an individual bishop or pope may possess as a God-given grace, but as a Christian individual, and not by virtue of his office. (The Ultramontane Church placed far too much weight—and far too heavy a burden—on hierarchical leadership, assuming that bishops and popes contained in themselves all the requirements of Christian leadership— institutional and organizational, spiritual and intellectual.) In fact, hierarchical leadership is rarely initiative-taking, and its most solemn responsibility is not the setting of agendas for the Church of its time, but the recognition and fostering within the community of those less predictable energies and gifts of leadership which God showers on those outside the hierarchy. Hierarchical leadership, properly exercised, is, in large part, about making space for non-hierarchical leadership.

Charismatic Leadership

Innocent III (1198-1216) was the most remarkable pope of the Middle Ages. All the ambiguities of leadership, and the delicate balance between office and charism, were in evidence during his pontificate. He was remarkably sensitive to the positive value of prophetic witnesses within the Church, and made strenuous efforts to retain such movements within the bounds of orthodox Catholicism. His most spectacular success here was the legitimation of the early Franciscan movement. Francis was an inspired and inspiring charismatic leader. All the early Franciscans were won for the movement by the electric personality of its founder.

Intellectual Leadership

In the same years, Innocent recognized another radically new movement which would also help transform Latin Christianity. To combat the theological arguments of the Cathar heresy, he authorized the preaching of a group of priest-preachers led by Dominic Guzman. From this little group, established at Toulouse, would emerge the Dominican Order, the most important intellectual force in the medieval Church, and which, in Thomas Aquinas, would produce the greatest Christian theologian since Augustine. The vision behind the Dominican order was utterly different from either the hierarchic and authoritarian model embodied by Pope Innocent, or the personality cult centered on Francis. The Dominican Order was astonishingly democratic, the brethren making corporate decisions, their structures of authority designed to minimize the domination of individuals and, instead, to focus and facilitate their shared vocation as preachers, teachers, and students of the Gospel—a democracy of the intellect harnessed to the propagation of the faith.

Threefold Authority

Cardinal Newman said there were three authorities in the Church: the authority of tradition, the authority of reason, and the authority of experience, which he placed respectively in the hierarchy, the university, and the body of the faithful. He added that if one of these three became dominant, the right exercise of authority in the Church risked being compromised. Each needs to be strong. Charismatic movements easily tend to give too much authority to experience. There are times when reason appears to be absolutized, or when groups give too exclusive a stress to tradition, to the detriment of reason and experience.

The word “authority” derives from “author.” A true authority is capable of authoring something in another. An authority in a particular field is capable of “authoring” understanding and knowledge of the field in others. In that respect, God is the Author of Life in both his first, and in his new, creation in Jesus Christ and his Church. The threefold authority within the Church is a participation in the authority of God who authors the new life of his new creation. If there is no life apart from the Author of Life, still, there are always limits to the degrees in which the authorities of the Church participate in the life that God authors within the body of Christ and the temple of his Spirit, and there will inevitably be tensions among the authorities in the sense that there is no authentically human life without tensions.

The threefold authority of the Church reflects the life of the Triune God, who is authoring its life. The hierarchical authority of the Church reflects the originating life of truth and love of the Father; the intellectual authority of the Church’s theologians and scholars reflects the Father’s Word of Truth in the life of his Son; the charismatic authority within the Church reflects the Father’s, and the Son’s, Spirit of love.

The Church Is Communication

Communication is at the heart of what the Church is all about (Avery Dulles, “The Church Is Communication,” an address at Loyola University, New Orleans, Jan. 19, 1971). The Church exists to bring us into communion with God and, thereby, to open us up to communication with one another. The Church is a communion. If communication is seen as the procedure by which communion is achieved and maintained, we may also say that the Church is communication. It is a vast communication network designed to bring us, individually and corporately, out of our isolation and estrangement into communion with God in Christ.

Inasmuch as the entire life of the Church is a communication process, we may also say that every major decision about the Church is, in one aspect, a decision about communication. Living in a world that is largely shaped by communications media, the Church must constantly keep abreast of new developments in order to keep its decision-making processes in pace with the current situation. A decision that is based on insufficient communication, or one that cannot be successfully communicated, is pastorally a bad decision, and may do spiritual harm. Concern for communications, therefore, is an important aspect of the pastoral responsibility of leaders in the Church.

The basic reality on which the Church is founded is a mystery of communication: the communication of the divine life to us through the incarnate life of Jesus Christ. Jesus, as a divine person, is God the communicator: he is the Eternal Word—the communicative self-expression of God the Father. As Incarnate Word, Jesus is the one who communicates through his bodily presence in our midst by speaking, by making gestures, by his whole way of life and, especially, by the climactic events of his death and resurrection. In the case of Jesus, it is literally true that the medium is the message. Through his incarnation, death, and resurrection as media, we are put in contact with the Good News of his saving advent, passion, and exaltation to the glory of God.

The rich variety of modes by which Christ himself communicated suggests that the Church, too, as an incarnational reality, may utilize all the possibilities of communication at hand in a given culture. It communicates not only by formal teaching—by doctrine—but also by dramatic action; by doing what it does, and by being what it is. Christians, whether clergy or laypersons, communicate the Gospel, or fail to communicate it, by their whole way of life, as well as by the words they speak or write.

Words have been the primary means of communication from biblical times until the most recent years. In biblical times the “word” meant chiefly the spoken word. In the first generation of the Christian era, revelation was transposed into the key of oral communication. The basic content of the faith came to be called the Gospel or kerygma. “Gospel” means good news, and kerygma refers to the way it is conveyed—namely by the proclamation of official heralds. The Church, according to the New Testament conception, is founded after Christ, on the prophets and Apostles, men of the Word. A prophet is one who speaks in the name of God; and an Apostle is one sent forth with a commission to bear witness.

Soon after the age of the Apostles, the Church entered an era of written communication. The Gospel then became a doctrine to be extracted from written documents—especially from the Bible, which was the “book” par excellence. In the manuscript culture of the Middle Ages, access to books was limited to a privileged class of literate persons—the clerks or clergy. The theologians, as specialists in the interpretation of authoritative texts, rose to a position of great influence. In the High Middle Ages, the university theologians became the unacknowledged rulers of the Church, the power behind the papal and Episcopal thrones.

Although the Middle Ages were a period of manuscript culture, this is not a complete description. The teaching of the bishops and theologians had to be communicated to the illiterate masses, and this was done through a great variety of media: homilies and inspired books, liturgical action, sacred chant, mystery plays, church architecture, stained glass windows, statuary, and painting. In the great cathedrals, the Christian revelation was conveyed by multimedia effects that might serve as a model in our own post-literate age.

Biblical End Notes

If seeing Jesus is to see the Father, hearing Jesus calling us friends (Jn 15:15) is to hear the Father calling us friends. In terms of John’s Gospel, Jesus is the “come and see” (Jn 1:39) of the befriending Father, calling us to accept his self-gift in the reciprocity (communion, community, communication) of friendship.

Salvation has a negative and positive aspect. It is the befriending Triune God’s deliverance from all the impediments to a life of communion, community, and communication in divine and human friendship. Salvation entails a God-given freedom from the impediments to such friendship, enabling our God-given freedom for it. The befriending Father and Son have given us their befriending Spirit for an eternal communion, community, and communication in divine and human friendship: eternal life and love in the communion, community, and communication of the Triune God. The gift of the Spirit is manifest in the friendship that unites the members of the body of Christ, the temple of his Spirit, so that we read that people shall know by our love and friendship that we are Christ’s disciples: in communion, community, and communication with Christ (Jn 13:35); that where two or three are gathered in his name (person or Spirit), people shall experience biblical knowledge or experience our befriending God among us.

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. On that day many will say to me ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’ And then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you evil doers!’” (Mt 7:21-23). Jesus implies the possibility of our self-deception regarding our communion, community, and communication with himself. Our religious formalism can lead us to believe that we “know” Jesus when we do not. The only kind of knowledge that counts for salvation is a biblical knowledge of Jesus in a personal communion of friendship. Loving Jesus for himself, rather than using religious forms associated with him for our own self-glorification and self-righteousness, is true communion with the Spirit of the Father’s love for Jesus, which is our salvation.

The friends of Jesus, the beloved Son, share the love and life that Jesus receives from his Father. Without the Holy Spirit of their reciprocal love, our claims to friendship with him are so much empty talk. Communion in the reciprocity of minds and hearts is our peace and salvation. Authentic Christian conversion can be undermined by self-deception that is always related to self-idolatry. There is always the risk of using our faith for our self-glorification, rather than for the glory of God. Hence, we are urged to watch and pray lest we lapse into self-idolatry.

The biblical banquet metaphor implies the divine and human communion, community, and communication that is our salvation, joy, peace, and fulfillment in the kingdom of God, the Host of humankind, the Generous One reflected in the generous persons who are his true image and likeness. God is always depicted as the Banquet Giver, the Host, the Generous One, who initiates and provides all that is required for the divine and human communion, community, and communication in joy and happiness under the sovereignty of his love.

This note was sent to us to add to the comments for Fr. Navone’s article, and is from a friend of his, Bill Burrows (a former editor of Orbis Books).

Dear Fr. Navone: Your communion article is absolutely wonderful. I just skimmed it and think it’s going to move me forward on a talk I’ve been blocked on for several weeks. I will read it slowly and carefully when I get a few chores done.

I simply could not move forward on a talk I was asked to give to Lutheran pastors at the OMI Our Lady of the Snows pilgrimage center. The topic they gave me is “proclaiming Christ in a pluralistic age” (for a group of a hundred or so pastors, including several bishops, among whom their new, female, presiding bishop). They are all members of what’s called the “Crossings” group, dedicated to working collaboratively to sharpen their preaching and making it relevant to the deeper spiritual problems of their people.

I think they’re going to love how I use you. I think I got asked to do the talk because I had contributed something on the Eucharist as a unified celebration in which we hear the word proclaimed and are challenged to join Christ in renewing his self-offering to the Father, mystically uniting ourselves with his sacrifice. I had prefaced it by saying I thought Lutherans and Catholics ought to get beyond arguing about the mode of the Lord’s real presence in the Eucharistic elements and learning from one another about communing with Christ in the Eucharist, bringing our lives to the Father in trust, asking the Spirit to perfect us in our struggle to die to self.

The structure of your communion article is what I needed.

I had already decided to speak about the Exercises and suggest that they find a good Jesuit who could interpret them for the Crossings membership, showing how they can be practiced to keep Christ the center of their lives. My fear is that – from what I can see in the advertising from some SJ retreat centers – some Jesuits have moved in at least a semi-New-Age direction with the Exercises. Crossings, by the way, is based in St Louis. If you were not able to come, any idea who there might be in the Midwest?

Pax tibi et tuis,

Bill Burrows (former editor of Orbis Books)

Fr John,this article reminded me of De Trinitatis in the seminary. Like that course, this article has so much to offer. I cannot digest it; distractions make it difficult to contemplate implications for life. I will work on it bit by bit; someday I may comprehend a little of what you write.

Couple of questions:

1. In the beginning of Christian communication was oral, then written, liturgical and artistic as you point out. Now communication is more and more electronic. Big data plays an ever more important role in our life as humans. How do we use this new way of communicating to give witness to the Trinitarian life you describe?

2. You speak so eloquently about our self deception related to self idolatry. Superficial divisions that exist among Catholics would seem to represent what you are talking about.? It is so easy to communicate in simple statements about one another. The commentator above makes a statement that reflects the danger of over simplification: “…some Jesuits have moved in at least a semi-New-Age direction with the Exercises.” Statements like this then become categories which must be rejected according our own self imposed ideology. How do we, as communities of believers, initiate processes of communication that will lead to conversion?