Just like the Church in the United States, the Irish Church is enduring hard times. However, what makes it so upsetting in Ireland … is the disappearance of what had been a Catholic society.

When first coming to Ireland more than a half century ago, I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Naturally, I was fascinated to land in a society that was impregnated with Catholicism.

While Catholicism was not the officially established religion, Irish society was overwhelmingly Catholic. The Angelus was played on the public radio; priests, brothers, and nuns wore their distinctive habits in public places; passengers in buses would invariably bless themselves when the bus was passing a church; and Masses, and other church services, were usually very crowded. Days of obligation had almost the aura of public holidays as many businesses and schools were closed.

Back in 1961, I admittedly found the prevailing Catholic orthodoxy somewhat uncomfortable, not because I dissented from it, but because in the United States, Catholic orthodoxy was in a minority position against both Protestantism and secularism. I sensed a lack of serious intellectual thought in Ireland about religious issues that confrontation with opposing views would have stimulated. There was piety and obedience in abundance, but a lack of thoughtfulness.

Although conservative in my religious and social perspective, even as an unmarried student in an America that was on the eve of the academic madness that swept the country in the 1960s, I was inclined to be a bit more outspoken and challenging while in Ireland. For example, when having lunch with a local Canon and his curate in County Kerry, I was “cheeky” enough to warn them that my impressions of Irish clergymen had been set by my reading of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Honor Tracey’s The Straight and Narrow.

In reality, my encounters with them, and other priests, were very positive. I came to take with a grain of salt the accounts I heard from older people in rural Kerry about the priests breaking up crossroad and house dances in the 1930s, and later. I came to suspect that a fear of the clergy and of teachers might be partly the consequence of a peasant mind-set: wary, originally of landlords, but also of the priests and the teachers who made up a large portion of the very small number of the population having more than a secondary education. In fact, at times, even those with a secondary education were a minority.

How different the more casual attitudes toward the clergy were, beginning in the late 1970s and early 80s. Significantly, these changed attitudes preceded the revelations of clerical sexual abuse. Since then, among many, casualness has been transformed into outright hostility.

But even before the revelations, religion was becoming less relevant for a great number. Their faith was drying up, which conditioned them for the changed atmosphere that was to come.

Much later thought and study on my part about the obedient and devout Catholicism of mid-20th century Ireland has made me wonder whether a certain amount of devotion could have been attributed to an unhealthy linking of religion and nationalism. For some, their unquestioning and even aggressive Catholicism might have been an expression of Irishness, much like enthusiasm for the national sports.

Along the same lines, Church leaders could be faulted for having rested on the soft deference they received from society and state in a quasi-established position.

Another factor was a simplistic Irish moral self-confidence resulting from neutrality during the Second World War. The strict censorship imposed by the government on what was happening outside of Ireland was understandable. The authorities were concerned that popular enthusiasm for any belligerents could endanger neutrality.

But that censorship and neutrality gave the Irish a sense of innocence and naiveté in contrast to the rest of the world. One manifestation of the same was the government’s hopeless attempt after the war, and at the outset of the Cold War, to gain worldwide sympathy to end the partition of Ireland. That was at a time when millions of people elsewhere had been displaced from their homes and nations.

Ireland emerged from provincial isolation in the 1960s and 1970s thanks to economic modernization and free trade, admission to the United Nations and, later, the Common Market, expanded secondary and third level educational opportunities, and television.

Naturally, historians of modern Ireland celebrate television’s having brought, into the public forum, issues that earlier had been limited to the confessional, the psychiatrist’s chair, and, no doubt, locker room banter. The reservations of some clergy and bishops about such openness made them the object of scorn.

No doubt, those clerics were picking the wrong fight. The problem was not the discussion of certain topics on the air, but the ultimate imbalance, and even, as was more recently borne out, outright fraud, in anti-clerical presentations. Maybe even more disturbing was not the liberalization, but the libertine-ization, of the airwaves, particularly the less serious fare, such as soaps, comedies, and even commercials, which probably have had a greater effect on the consciousness of the popular mind than serious discussion programs.

In keeping with the expansion in higher educational opportunities, the Catholic hierarchy’s restrictions on Catholic attendance at Trinity College were removed. At the same time, the de facto Catholic universities in Dublin, Cork, and Galway were well on their way toward secularization. Today, Trinity students are as overwhelmingly “Catholic” in the ethnic, rather than religious, sense as the other institutions

These developments parallel what has happened in a great number of the Catholic universities in the United States. They have become Catholic in the same way that many of the Ivy League schools were Protestant, that is, their character at their founding.

Another parallel in both the Irish and American Churches was an enthusiastic misinterpretation of the Second Vatican Council. Freewheeling liturgical experimentation, and blunt challenges to episcopal authority, were not as open here. But there was among the ordinary clergy and religious, not to mention the laity, a mixture of passivity and thoughtless acceptance of change, as well as an increasing assumption that almost anything was permissible.

One area where this was evident was the individualization of the hitherto communal life of religious orders, which has contributed, in no small way, to the diminution in their numbers. Another was in church architecture where structures more and more assumed the character of gymnasia, meeting halls, or modernized replicas of Newgrange.

This spirit was most disastrous in the dilution of religious instruction. There was a passive assumption that children were receiving proper catechetical instruction in the schools under Catholic management. So long as the First Communion and Confirmation exercises were conducted, everyone seemed content, with little thought as to the content or depth of religious instruction, or encouragement of religious devotion.

One cannot help but suspect that what has happened can be partly attributed to the lack of serious religious faith on the part of many instructors. Children in the lower elementary classes are now the third generation experiencing this sad dilution. Even though Catholic management might continue in a greater number of schools than would please the Minister of Education, it will scarcely get to the root of the problem.

Unlike 50 years ago, when Irish youngsters instinctively blessed themselves when passing a church, or knelt at their bedsides saying their night prayers, one wonders how many of the present youngsters can name the Seven Sacraments or can recite the Ten Commandments, not to mention attend Sunday Mass with any regularity.

The lessening of religious sensitivity, the growth of indifference, and the actual loss of faith, occurred almost unawares. It was unlike what happens when an overtly hostile political regime imposes restrictions on religion, such as in Eastern Europe right after the war.

In fact, leaders of the Irish Church had an unwarranted sense of confidence in the late 70s and early 80s because of certain events. Among them were the enthusiastic reception by the Irish to the first ever papal visit by John Paul II in 1979, the overwhelming approval given in the 1983 referendum to the anti-abortion amendment to the Irish constitution, and the comparable-sized rejection in a referendum, three years later, of a proposed amendment to allow divorce.

Sure enough, within a decade of the “Church victories” in the 1983 and 1986 referenda, things turned quickly the other way. The first crack in the so-called clerical dominance was the “X” case decision by the Supreme Court in early 1992, allowing an abortion in a case where the expectant mother was threatening suicide, and basing the decision on the very wording of the right to life amendment itself about the equal right to life of the mother.

Attempts later that year to reverse the decision by constitutional amendment were rejected by almost two-thirds of the voters, while liberalizing measures allowing the distribution of information about abortion, and freedom to travel abroad to obtain an abortion, were approved by a three-fifths margin.

A further referendum in 2002, seeking to reverse the “X” decision, also failed, but by a much closer vote.

In 1995, by a margin of less than 51 percent, a constitutional amendment allowing divorce was approved in a referendum. Some commentators argued that the outcome was the beginning of the slippery slope by which Ireland would move toward a California lifestyle. Statistics on increased marital breakdown, as well as increased cohabitation, would bear out such apprehensions.

The next decade and a half would be a long night of the soul for the Catholic Church in Ireland in view of the numerous revelations and accusations of sexual abuse by priests and religious in parishes, schools, and, especially, industrial homes, and hierarchical lack of concern. Public commissions confirmed the reality of the abuse, and the state established a mechanism for financial retribution to those, such as orphaned or delinquent children, who had been placed in the industrial schools run by religious orders at the behest of, and with the financial aid of, the state.

Of the final cost for the redress of over a billion euros, only a small fraction was drawn from the religious orders. This greatly annoyed those anxious to punish the Church. However, fury at the Church’s not bearing a greater portion of the cost seems to have abated when the taxpayer had to assume the enormously larger fiscal burden consequent to actions of cowboy bankers.

Also, many did recall that the industrial homes were providing a relatively inexpensive service, wanted by the state, and desired by a public anxious to clear from sight troublesome youngsters. Interestingly, the testimony of many receiving redress awards did appreciate the work of most of the religious caring for them. A major part of their complaint was about a small minority of the numerically inadequate, and poorly trained religious staff, as well as bullying by older students.

The more recent McAleese report on the Magdalene Laundries, another type of institution run by nuns for troubled, orphaned, or unmarried pregnant girls, repeated the same mixed story of abuse and maltreatment, but also of appreciation.

The actions, admittedly belated, by the Irish hierarchy, such as their drafting a framework guideline for dealing with abusive clergy, and engaging their own commission for investigating the various dioceses, suggests that the Church is taking the problem in hand. The international inspectorate that Pope Benedict XVI commissioned to examine the Irish Church in general, including the formation of priests, and his appointment of an energetic younger Papal Nuncio are further signs of the Church bringing the situation under control.

Of course the scandals in the Irish Church are not worse, and perhaps less outrageous, than what has occurred elsewhere, including the United States. What made it so distressing was the impression, which was not invalid, of an intensely devout Irish people being betrayed by so many clergy.

It will take scholars decades to come to terms with the reasons for the outbreak of clerical sex abuse in the mid-20th century. Was it unique? Was it a consequence of social, sexual liberality? Were those vowed to celibacy inadequately prepared? Were there too many priests and religious, and were many in orders for inadequate, or the wrong, reasons? Were the hierarchy unconscious of the abuses, or did they naively assume they could be easily corrected with psychological remediation?

At any rate, the Church has seriously undertaken the necessary remedial steps. However, as is often the situation in history, severe hostile reaction, even revolution, often occurs after remedial actions are undertaken. The revolution in France occurred at the time when the French peasantry were probably better off, and freer, than most of the peasantry in the rest of Europe. The Bolshevik revolution occurred a decade after the beginning of constitutional reform in Tsarist Russia.

With that in mind, one is apprehensive about the position of the Church in contemporary Ireland. There is a hostile, unfair, and often, dishonest atmosphere in the media.

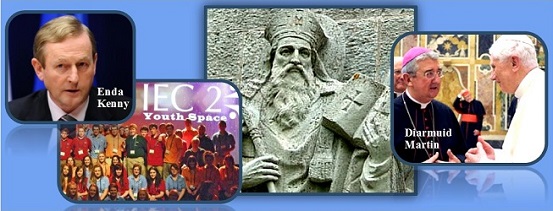

That intolerance and disregard for religious, especially Catholic, positions, by many in Irish radio, television, and the press has formed the thinking of political speechwriters, particularly those of the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Enda Kenny of Ireland. That was obvious in their penning of his speech for the closing session of the Dáil in 2011 that deplored the Vatican for having “contributed to the undermining of the child protection frameworks and guidelines of the Irish State and the Irish bishops.”

In his speech, the Taoiseach noted “the dysfunction, disconnection, elitism—that dominate the culture of the Vatican to this day,” where “the rape and torture of children were downplayed or ‘managed’ to uphold instead, the primacy of the institution, its power, standing, and ‘reputation.’”

Continuing to ride the wave of anti-clericalism so prevalent in the Irish media, Enda Kenny insisted that the Irish Republic of 2011 was not Rome, and that he would refuse to be intimidated by “the swish of a soutane” and “the swing of a thurible.”

The Taoiseach’s rebuke of the Vatican was soon followed by the announcement by the Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and Minister for Foreign Affairs, Eamon Gilmour, that Ireland will no longer maintain a resident ambassador to the Vatican. Ostensibly, this was done for economic reasons, although the annual budgets of many consulates, never mind embassies, to the Vatican greatly exceed that.

Because the Vatican does not accept as ambassadors anyone who is simultaneously the ambassador to the Italian state (much as Ireland would not accept as ambassador anyone simultaneously serving as such to the Court of St. James), Irish dealings with the Vatican (with whom Ireland has had one of its oldest diplomatic relationships) henceforth, will be conducted through the secretary of the Department for Foreign Affairs. 1

Given that officer’s very full agenda, dealings with the Vatican will necessarily be greatly minimized. Senior former Irish diplomats, including a former department secretary, have regretfully noted that this is a great loss for Irish diplomacy in terms of information gathering and international influence.

But more disturbing than the hostility of political leaders and the media is their arrogance in suggesting how the Church should change to meet their agenda. Typically, when Archbishop Diarmuid Martin acknowledged in December of 2011 the decline in church attendance, religious vocations, and even financial contributions, The Irish Times suggested as “a road to regeneration” that the Church consider “an end to celibacy and acceptance of married priests; and, eventually, the ordination of women to the priesthood.” 2

Many in the Church share this spirit of accommodation with the Times. For example, a speaker at a meeting in Cork of the Association of Catholic Priests in October, 2012, criticized those Church figures who insisted on such things as: “the importance of clerical dress;” training of priests “separately from non-clerical students;” taking “a strong line … against the use of contraceptives;” viewing homosexuality as “a disordered state;” regarding a male clergy as “an infallible truth of our faith;” and excluding from episcopal appointment supporters of the ordination of women or anyone “‘soft’ on issues of sexual morality.”

To him, the Vatican Council was “the beginning of a new openness in the Church,” whereby “we are called by the Holy Spirit to move on beyond the necessary compromises in the Council documents.” A fresh look at “the burning issues and new situations of today,” he said, would suggest “that much of the theology of sexuality preached in the Church in the past was simply wrong.” 3

It was against the background of political and media hostility, as well as in-house criticism, that the International Eucharistic Congress (IEC) was held in Dublin in June of last year.

What a striking contrast with the Congress held 80 years before. Then, military contingents met, and escorted ecclesiastical dignitaries arriving at Dun Laoghaire, the streets and residences of the city were decked with national and papal colors, and thousands attended Benediction Service at O’Connell Bridge, never mind the more than a million at the closing Mass at Phoenix Park. In 2012, a visitor to the city would hardly be aware that the Congress was taking place.

While the regular meetings of the Congress at the Royal Dublin Society were very well run and well attended, they obviously paled in comparison to the 1932 Congress, even if one takes into account the packed final Mass at Croke Park, attended by the President, the Taoiseach, and the Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland.

However, while not having the numerical strength of the earlier Congress, the 2012 gathering displayed an intensity and commitment that leaves one hopeful for the Church in Ireland. It was not only the quality of the liturgies, the homilies, the speakers and workshops, but the devotion, especially of so many young people.

Furthermore, important gestures of repentance for the abuse of children by clergy and religious, as well as the tardy, if not indifferent, response by some of the hierarchy, were made, including a visit to the pilgrimage site in Lough Derg, County Donegal, by Marc Cardinal Ouellet, the Papal Legate to the Congress, and Archbishop Charles Brown, the Papal Nuncio to Ireland.

Inevitably, cynics would claim, as did one letter writer to the Irish Times, that, “in time, the 2012 Eucharistic Congress will be seen as the swan song of the Catholic Church” and “Ireland would be a better place” without it. More accurate would be to see the Congress as less than a swan song of the Church, than as an expression of its vitality, the same vitality possessed by the early Christians of the first, second, and third centuries, who were regarded as so out of touch with the prevailing ethos of the Roman Empire.

One has to acknowledge that the Church has a diminished position in Irish life—culturally, socially, and politically. Ireland is not the fabled land of saints and scholars. That image, no doubt, was overdrawn, but was not without having been of some validity, especially if measured by the impact of the Irish immigrants, clerical and lay, on the development of the Church in the United States, as well as by the disproportionate Irish presence in missionary fields throughout the world.

Just like the Church in the United States, the Irish Church is enduring hard times. However, what makes it so upsetting in Ireland—both to the faithful in Ireland, as well as to those who look from abroad—is the disappearance of what had been a Catholic society. Nowadays, the voice of the Church is one of many competing voices for public attention, and that voice is often barely audible.

Only as of late has the Church in Ireland been confronted with the need for a vigorous defensive position. Perhaps, softened by a possibly insincere deference, Church leaders were not readied for what has happened. But, it is always in such times that the true heroes—and if need be, martyrs—emerge.

Consider certain specific issues.

While the constitutionality of the Orwellian-titled Defense of Life in Pregnancy Act will be challenged, the Right to Life cause in Ireland, and the Catholic Church, will have to be prepared to struggle at various lower, and more local levels, even at times waging campaigns of civil disobedience, beginning with resistance to attempts compelling personnel and institutions to disregard their personal and organizational ethos.

On the issue of religious education—besides insisting on more appropriate religious instruction in existing denominational schools—perhaps, the time has come to create a distinct parochial school system that could charge tuition, but also demand tuition vouchers, where the state could compensate those families not utilizing the state or national school system.

Another concept bearing some consideration would be the development—but only if done on a very high quality basis—of Catholic colleges. Its students could then pursue their postgraduate studies at the various other universities in Ireland and elsewhere. A certain number will invariably also enter seminaries and novitiates.

There is potential for all of these things in Ireland, but central is the Faith itself, on which all else depends.

Naturally, adherence to the Faith implies acceptance of those words of Cardinal Ratzinger, to which the Taoiseach took such exception, specifically that the Church not be governed simply by “Standards of conduct appropriate to civil society or the workings of a democracy.”

By not accepting the changing values of the democratic process, the faithful may well become a remnant in what had been a Catholic society. That burden will be all the more daunting given the increasing intrusion of state authority in individual, familial, and communal matters.

- Irish Examiner, Feb. 13, 2012; The Irish Times, Feb. 21, 2013. ↩

- The Irish Times, Dec. 17, 2011. ↩

- Donal Dorr, “Remember the Miracle of Vatican II,” Oct. 13, 2012, www.associationofcatholicpriests.org ↩

very telling omission in all this….ALCOHOL. The omission of ALCOHOL and its devastating effects on everything Irish can only be attributed to a “blind spot” of self-admission.

Modern Western Catholicism is not stable. I have never heard a modern Ordinary Form priest defend the unique status of the Catholic Church as Christ’s true Church. I have never heard one expound upon and defend the Church’s noble teaching of sexual morality. I get the impression that most believe that the Catholic Church is just one option among several viable denominations.

I get the sense that modern Western Catholicism does not even believe in itself. Absolutely horrid catechesis combined with lingering impacts of the sex abuse scandals.

Christianity, including the Catholic branch, is dying in the Western World. It may be growing in the backward parts of the world but in Europe and America it is dying. Various political reasons have kept it afloat and seemingly healthy: a way of resisting Communism in Poland and Eastern Europe; a way of surviving in a Protestant world in the USA; a way of resisting English and American culture in Quebec Province in Canada. But with the fall of Communism and the weakening also of Protestantism many find churchgoing no longer useful. And a popular and celebrity pope like Pope Francis can only stem the decline temporarily.

Catholicism’s decline means the decline of much of Western culture. While Christianity did not start out as Western the advance of Islam made its life increasingly possible only in Europe and its white colonies. It is a shame, as death usually is, but after 2000 years can one really expect anything else. Few Catholics believe what Jesus told Peter, that the gates of Hell would not overcome the church. Few priests and bishops and even popes have believed this. Had Pius XII believed this would he have been so fearful to speak out against the Nazis?

I am glad I just discovered HPR. There is a demographic collapse going on in the developed world and in most of the undeveloped world too. The only two exceptions are Israel and the USA, and the latter is hanging in the balance. The most religious (such as Evangelicals, conservative Catholics and haredi and orthodox Jews) are thriving while secularists and all others in between are literally dying. I don’t understand why this has to be so, but David P. Goldman makes the case of “nationalist” Christianity as the main reason in his book How Civilizations Die. I would like to know if Mr. McCarthy has read the book and what he thinks about the whole thing. Phillip Longman and Eric Kaufmann, liberal secularists both, have written similar books on worldwide demographic collapse.

I am not Irish but I knew many Irish people from both the North and the South and this applies indeed to all the practising Catholics whom I knew in my youth up till the early 70s, all of us knew our Faith and kept its teachings more or less well. I never had to argue about any doctrine or teaching, not even Humanae Vitae! We knew what we believed and why we believed it. It did not matter what level of education a person had; we had all been thoroughly grounded in the Penny Catechism and that was a solid foundation, though there were some more educated in the Faith but the basics we could all explain as St. Peter exhorted in his epistle to the early Christians. I knew only one Catholic who deviated from the Church and that was an Archbishop ( whom I met, briefly, in his retirement). I thought he was mad. I think it significant that it was a high ranking cleric who thought it appropriate to scandalise a young person with such open opposition to the Church’s teaching. The trouble with the Church today is that education in the Faith ( such as the Catechism) has been neglected for progressive discussions and teaching about other world religions. Many Catholic children do not know their basic prayers let alone the Commandments or Sacraments. Homilies almost never teach the faith or explain the encyclicals of the Holy Father ( Blessed John Paul 11’s teaching on the Theology of the Body is a great resource hardly known to most Catholics); Catholics are never

challenged about their conduct. Let Bishops become what they are meant to be – the teachers and Shepherds of their dioceses and let us teach our children the Faith. Most parents (and even teachers) today cannot teach the Faith because they were never taught. The Penny Catechism may have been taught by rote but it was taught and was an invaluable base from which young people could grow in the Faith. For over 40 years at least there has been an almost total neglect of the Faith in so- called Catholic schools and most priests keep off the ‘dangerous’ topics lest their parishioners go to some other parish and the collections go down. Let us return to the ways of the Church up to the mid 60s and see whether we can also reach again the knowledge and love of Christ in His Church which in my memory was common.

Tradition is dead in in all our world—-replaced by political correctness –that includes the Irish—Sad

I found it striking that in an article on the Church in Ireland, there was no mention of Jesus Christ. Could it be that a Church in Ireland lost its mission spirit and members became cultural Catholics.

Perhaps the military support for Church was more important than lay people engaged as missionary disciples of Jesus Christ proclaiming the Reign of God.

“What a striking contrast with the Congress held 80 years before. Then, military contingents met, and escorted ecclesiastical dignitaries arriving at Dun Laoghaire, the streets and residences of the city were decked with national and papal colors, and thousands attended Benediction Service at O’Connell Bridge, never mind the more than a million at the closing Mass at Phoenix Park. In 2012, a visitor to the city would hardly be aware that the Congress was taking place.”

Same thing happened to Ireland that happened to the world, vat 2, cheap mass production of consumer goods made things relatively inexpensive to purchase, consumerism and mass media provide all sorts of distractions to tempt people. It will all end one day if we believe the Children of Fatima. The faith will survive in Ireland even if the majority of the country falls into secular consumerism. Tthese are people that hid behind rocks to hear mass to avoid the English. As Saint Patrick confirmed the faith will survive to the end.

It seems that in the US and Ireland some catholics have not put away the things of a child as Paul tells us. Faith Hope and Love these three but the greatest is love. of God and neighbor for the sake of God. This excludes the State infringing on and attempting to displace the Catholic church.. From the Holy Spirit this is impossible.

I have been to Ireland many times over the last 30 years. The first few I saw an Ireland populated with children, all in school uniforms, flocks of them. My last trip I saw none. Ireland has succumbed to contraception, the worst plague, in both blood and treasure, ever visited upon mankind.