The Catholic sacramental perspective continues (consciously or not) to inspire the works of historians who recognize the importance of material reality—of politics, society, economics, the arts, and all the habits and institutions of human civilization—as important and worthy of the most serious consideration.

In The History of a History Man—the memoirs of the late historian, Patrick Collinson, published in 2009—Collinson considers the historiography of the English Reformation in which he made his mark. “When I started,” he wrote, “there was no such thing (as a Protestant historian). There were, of course, Catholic historians, who were suspect. My teacher, J.E. Neale, almost said that the only good Catholic historians were the dead ones—except that the dead ones were especially bad. They inhabited a ghetto, and wrote for a ghetto. We non-Catholic historians were, well, just historians … telling it the way it was, without the taint of religious bigotry.” Collinson lived long enough, and proved a sensitive enough scholar, to admit the injustice of the traditional, anti-Catholicism of many English historians. He greatly admired the work of the Irish Catholic historian, Eamon Duffy (“who writes much more persuasively than I could ever hope to do”), and admitted that when Duffy asked, “If I am a Catholic historian, is not Patrick Collinson a Protestant historian?” Duffy was “right to ask the question.” 1

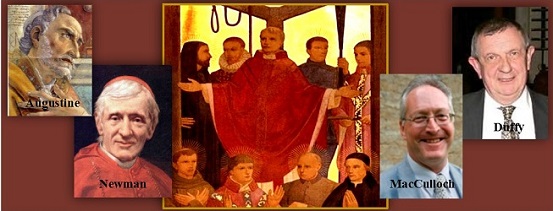

Just when the old prejudices seem to be dying out, however, they raise their ugly heads again, this time in the work of Diarmaid MacCulloch. MacCulloch is an Oxford historian, and former Anglican deacon, whose works on religious history (including a survey of the Reformation, a long history of Christianity, and most recently, an intriguing work entitled Silence: A Christian History) have drawn critical acclaim. In a recent review of Eamon Duffy’s Saints, Sacrilege, and Sedition, MacCulloch raises the old question. “At times,” MacCulloch wrote in the July 27, 2012 issue of The Guardian, “Duffy ceases to be a Tudor historian who is a Catholic, and becomes a Catholic historian. That will please many, but it’s a shame: almost (italics added) as bad as being a Protestant historian, rather than an historian who is Protestant.” MacCulloch’s accusation caused a minor tempest among historians, and in a more recent interview in The Spectator (April 6, 2013), he responded to charges of anti-Catholicism, insisting that he is not anti-Catholic, but “anti-curial,” mainly due to the Church’s teachings on sexuality (MacCulloch is openly gay, which led to his own estrangement from the Church of England). His criticism of Duffy, he insists, was not the result of any religious prejudice, but a register of his fear that the new revisionist interpretation of Tudor history pioneered by Duffy—an interpretation which maintains that the 16th century English Catholic Church was not corrupt, but vital and dynamic, as reflected in the popular beliefs of Englishmen at the time—is “in danger of becoming an orthodoxy, just as the old Anglican position was.”

But, as they say, you can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube. MacCulloch’s criticism demonstrates a continued prejudice against Catholic history that demands consideration. Once again, the questions must be answered—can a Catholic be a good historian? Does the Catholic faith negate historical objectivity? Are faithful Catholics hopelessly biased in interpreting the past, and especially the religious history of the past?

Two points need to be made upfront. First, being a “Catholic historian” does not excuse a scholar from the necessity to be thorough, competent, and professional. No good is served by replacing solid history with faith-filled history. The two must be compatible. As Christians, we believe that God created the world in his own image, and that all the good gifts of the world—including human intelligence—deserve cultivation in an effort to understand created nature, and, ultimately, to serve God. Secondly, “Catholic history” should transcend ecclesiology. The structures of the Church have evolved over centuries, and the historian should sympathize with, and understand, those changing structures. To tie historical scholarship to one period, or one model of Church governance and culture, feeds into the prejudice of non-Catholics who decry Catholic triumphalism, and distort, or misunderstand, the politics of the Catholic Church. The Catholic historian should recognize the essential spirit and beliefs of the Church, which transcend politics, without unduly favoring a particular historical or cultural model. John Henry Newman said it famously, “To be human is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.” Historians deal in the currency of change, and the challenge of the Catholic historian is to recognize and analyze change while respecting the fundamental spirit of human society as created by a good God.

I point out the need to cultivate excellence and avoid political extremism with some hesitation, because no one seems to mind when historians of a decidedly secular ideological bent occasionally take shortcuts, express unsubstantiated opinions, or wax political in the course of their work. And, of course, all scholars work from some ideological perspective, whether they admit it or not. All humans are conditioned by their temperament, upbringing, opinions, and culture to see the world in a certain way. Marxists do so, atheists do so, post-modernists do so, radicals do so—and they all profess that their perspectives, grounded in their firm faith in a particular ideology, actually enrich their scholarly work. Other scholars accept those perspectives at the same time that they question the perspective of religious faith. Why question a Christian (Protestant or Catholic) perspective, and not other more secular outlooks? Why can’t religious faith be seen as adding a rich dimension to historical scholarship? Using the logic of the academy, what is the difference between Marx’s iron law of history (i.e., dialectical materialism) and the Catholic sacramental perspective? But, then, prejudices are, by their very nature, often irrational. So I emphasize the need for excellence and political objectivity for historians of all perspectives, and ground that focus in specific Catholic Christian values to demonstrate the veritable richness of a faith-oriented perspective on historical scholarship.

When I teach historiography to undergraduate students, I emphasize certain key elements that define history—at least as developed in the western tradition over many centuries. If history aims to relate true stories about the human past (to paraphrase the historian Robert Conkin 2), certain preconditions are necessary for the telling of authentic human histories. For a civilization to develop a historical sense, its culture must prize history, must see an importance to telling stories about the past. It must recognize some purpose to such stories, else recounting the past becomes a meaningless exercise. It must proceed from some understanding of human nature, for stories about the human past are not the same as stories about other natural phenomena. Human stories must take into account the eccentricities and inconsistencies of human beings. As I tell my students, when “doing” history, 2 + 2 does not always equal 4 (i.e., similar preconditions or “causes” do not always yield the same results). Good history, then, must be able to account for the times when past cultures and people made unique decisions that led down different historical paths, even when those decisions seem so obviously irrational or misguided, at least from our present perspective. Accounting for historical differences necessitates some sympathy for the people of the past—misanthropes do not make good historians. Good historians must also cultivate the art of storytelling. Not everyone tells good stories in a manner that attracts, informs, or entertains. The best history is useless if not told well. Finally, the historical perspective demands a critical capability. Historians cannot always take the past at its word; they must dig deep and question surface explanations to get to the heart of the historical matter.

An emphasis on the importance of the past, and the purpose of telling true stories about that past, an understanding of human nature, and a sympathy for human beings in other times and places, and the ability to tell stories in a meaningful and critical manner—these are among the important elements of good history. Can a Catholic perspective reflect, even enrich, these elements? I think so. Indeed, the Catholic Christian perspective has contributed greatly to the development of history as an intellectual pursuit in western civilization. From St. Augustine to Christopher Dawson, a Catholic perspective has proven seminal to the tradition of western historiography.

Regarding the importance and purpose of history, Christian thought drew on Jewish antecedents, especially the cosmology of the book of Genesis. God created all things, and saw that they were good. God created human beings in his own image and likeness, imparting a special dignity to humanity. During his time on earth, Jesus used the things of the earth to glorify God, and dignify human beings. The institution of the Eucharist provides the ultimate expression of this sacramental perspective. God comes to humans through visible things, so that everything (and every time) assumes importance as possible vehicles through which to discover and honor our God.

Christian thinkers (influenced by Hebrew thought) early on developed an appreciation of the meaning of time as the medium through which God communicated with mankind. Just as the Old Testament chronicles the unfolding revelation of God to his chosen people, the coming of Christ, and his sacrifice, brought ultimate salvation (once and for all) to humankind. God chose to come to earth in human form—Jesus was born, matured, suffered, and died in human time. Christ’s sacrifice, then, sanctified human history, and his promise of a Second Coming assures attention to present and future. Time has a purpose and an ultimate end.

St. Augustine built on these fundamental Christian beliefs in The City of God to define a mature Christian philosophy of history. Augustine met pagan Roman charges, that the Christians had weakened Roman society to the point that it proved vulnerable to barbarian invasion, by reminding Romans that all empires rise and fall. It is the nature of earthly things to decay and die. During our lifetimes (and during the tenures of great cultures), it is important to use the good gifts God has given us, to work for a world that is more reflective of the goodness and grace of God, and especially to work for peace. But all our efforts cannot prevent the reality of death and decline, for only the City of God is perfect and permanent. While we work for peace, we anticipate ultimate communion with God in heaven. Augustine’s insights inspired a wave of Christian historiography, including the work of the Venerable Bede, who affirmed the practice of dividing human history into eras, divided by the birth of Christ (B.C. and A.D.). Late antique and medieval Christian historians mined the past for illustrations of the good works of saintly human beings, and signs of the Second Coming of Christ in glory.

The Catholic sacramental perspective continues (consciously or not) to inspire the works of historians who recognize the importance of material reality—of politics, society, economics, the arts, and all the habits and institutions of human civilization—as important and worthy of the most serious consideration. Time has meaning and purpose for faithful Christians, especially for Catholic Christians drawn to a sacramental perspective, and history is important both in its own right as a testament to the dignity of humanity (and, at times, to the sinfulness of man), and as a medium through which God continues to impart grace to his human creation.

A Catholic perspective also enriches historical perspective by providing a rich and nuanced philosophy of human nature. Human beings, made in the image and likeness of God, but fallen from immediate unity with God through sin, possess an inherent and inalienable dignity. Graced by God with the gift of free will, human beings make decisions that determine their ultimate fate. The sinful nature of humanity means that sometimes humans make bad (or even evil) decisions. Good or bad, humans live with the consequences of those decisions. Historically speaking, that means the decisions of human beings merit attention and consideration. Nothing is necessarily fated. No iron law of history predetermines the course of events. God’s Providence looms over creation and contextualizes, but does not predetermine, human actions. Whereas some historical philosophies struggle to explain the nature of human wrongdoing and evil, as well as the possibility of human genius and goodwill, a Catholic Christian appreciation of human nature offers perspective for all—“the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

A sense of purpose, and a philosophy of human nature, allow Catholic historians the possibility of sympathizing with historical figures. In The Idea of History, the influential English historian and philosopher R. G. Collingwood suggested that, given the elusive nature of the past, history is best described as a process of thought. The practice of history, Collingwood maintained, is the art of reconstructing imaginatively the mindset of previous generations. The process of reconstructing the thought of the past requires, in the words of Collingwood’s recent disciple, Niall Ferguson, “an imaginative leap through time” in an effort to find lessons applicable to the present. 3 In my view, the Catholic historian is uniquely prepared to pursue such a history. Catholics prize humanity as a true communion of believers—past, present, and future. This human community, transcending time, allows us to “commune” with the saints and invoke their intercession. Such a mindset lends itself to the development of a rich historical imagination. For the best Catholic thinkers, the past is truly alive as part of the continuing human drama of birth, death, and resurrection.

If so, the past becomes a kind of seamless story to be told, and retold, by succeeding generations. Catholic poets and novelists have offered numerous depictions of the drama of human life and death, including stories of unlikely saints and heroes finding meaning in the most mundane, as well as the most extraordinary, of human situations. This Catholic zest for storytelling enriches historical perspective, and contributes to the ongoing task of crafting an historical narrative that is both universal (i.e., common to the human condition) and particular (unique to each generation and culture). Catholic, and Catholic-minded, historians offer an important contribution to this ongoing historiographical enterprise.

Finally, the tradition of Catholic thought emphasizes the compatibility of faith and reason, belying the charges of some critics that Catholic historians are biased and unable to reconcile the demands of historical scholarship with the doctrinal claims of their faith. The Catholic tradition recognizes that the mind is a gift from God and, like all God’s good gifts, should be cultivated and expanded. Reason aids the spirit in the quest for truth, and faith and reason can never truly be at odds. A host of Catholic intellectuals, from St. Augustine to John Henry Newman, have applied their minds to serious questions regarding the human condition. Indeed, Augustine and Newman were both historical-minded thinkers who contributed greatly to our understanding of the past. Augustine became a Christian partly because of the rational dimension of Christianity, and his thought laid the groundwork for a Christian philosophy of history. Newman converted to Catholicism after a careful study of early Church history, and his writings offered sensitive explorations of a variety of topics, from the nature of faith to the development of Christian doctrine. In more recent times, Christopher Dawson and Eamon Duffy attest to the influence of Catholic historical thought. Dawson, first holder of the professorial chair in Catholic studies at Harvard University, analyzed the role of Christian faith in the shaping of western culture. Duffy, professor of the history of Christianity at Cambridge University, has changed the direction of English Reformation studies with his ground-breaking work on popular religious mentalities in early modern England. Both Dawson and Duffy are serious-minded Catholics whose faith informed their scholarly efforts. 4 Their contributions as critical historians cannot be discounted by any serious student of the past.

A brief review of the elements of the Catholic intellectual tradition attests to the value of “Catholic history.” Catholic thought emphasizes the importance and purpose of the past, offers a philosophy of human nature that explains the vagaries of historical events, and allows sympathy for historical figures, prizes storytelling as a means to understanding the drama of human life and death, and insists on the compatibility of faith and reason. These elements, reflected in the thought of thinkers like St. Augustine, John Henry Newman, Christopher Dawson, and Eamon Duffy, have helped shape the western historiographical tradition. To deny that attests to the prevalence of anti-Catholicism as “the last acceptable prejudice.”

- Patrick Collinson, The History of a History Man, Or the 20th Century Viewed from a Safe Distance (Boydell Press, 2011): 61. ↩

- Paul K. Conkin and Roland Stromberg, Heritage and Challenge: The History and Theory of History (Forum Press, 1989): 130. ↩

- Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (Penguin, 2011): xxi. ↩

- See, for instance, Duffy’s popular essays on faith in Faith of Our Fathers (Continuum, 2004) and Walking to Emmaus (Burns and Oates, 2006). ↩

[…] Love – The Reg Is Plan B an Abortion Pill? – Kathleen M. Berchelmann MD, Aleteia On Catholic History – Dr. Richard J. Janet PhD, Homiletic & Pastoral Review Fatal Errors with Sola […]