Key to Balthasar’s response to modern biblical studies is his concept of beauty … Balthasar links beauty to human perception, and the way human beings gain knowledge.

Over the past 100 years—amidst the confusion and darkness surrounding the Church’s attempt to evangelize a post-Kantian world—few figures have aided the Church more than Hans Urs von Balthasar. At his death, Cardinal Christoph Schönborn described him as a “thoroughly Catholic figure” with an “incomparable reverence for the Word of God” who found “a sure path between the reductionism of a one-sided use of the historical-critical method and the dangers of fundamentalism.” Schönborn praised his approach to Scripture because Balthasar recognized the “inner unity of ecclesiality and spiritual experience.” 1 Pope Emeritus Benedict (then Cardinal Ratzinger) also confirmed Balthasar’s works, saying that in extending him the honor of becoming a Cardinal, “the Church, in its official responsibility, tells us that he (Balthasar) is right in what he teaches of the Faith, that he points the way to the sources of living water … (he was) a witness to the word which teaches us Christ, and which teaches us how to live.” 2 Finally, St. John Paul II also described Balthasar after his death as “an outstanding man of theology and the arts, who deserves a special place of honor in contemporary ecclesiastical and cultural life” and whose person and life’s work were held in “high esteem … by the Holy See.” 3 While there are certainly controversial areas of Balthasar’s theology (especially his position on Christ’s “abandonment” by the Father), this essay will examine one reason why he was praised by such eminent Catholic theologians. It will examine how the first volume of his series, The Glory of the Lord, entitled Seeing the Form, can help the Church respond to the crisis in modern biblical studies, by appealing to our encounter with beauty. By incorporating the insights of modern historical studies into a hermeneutic of faith, Balthasar provides the light necessary to overcome the problems of the historical-critical method. Furthermore, his project of “theological aesthetics” reveals that Mary should be the model of the Church’s biblical interpretation.

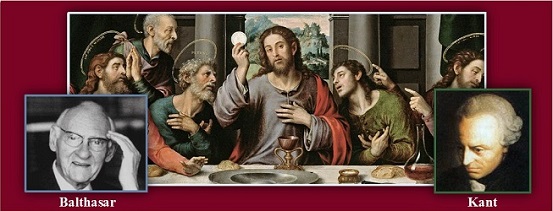

The Problem of Modernity: The Legacy of Immanuel Kant

Few people have influenced modern society more than Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Building on the work of Bacon, Descartes, and Hume, Kant sought to reconcile empiricists and rationalists in their search for knowledge. While he wrote many things, Kant is best known for establishing the foundation of modernity by absolutizing the split between the person and reality, between the thinking subject and the external object. While an adequate summary of Kant’s philosophy, and the influence of the Enlightenment on modern society, is not possible in this essay, a brief treatment is helpful in understanding how Balthasar’s project responds to Kant, and aids the Church’s biblical hermeneutic in the modern world.

Kant’s legacy is evident whenever one encounters the modern dogma that humanity is cut off from genuine knowledge; that our mind’s innate concepts and categories constitute reality as they impose themselves on an unintelligible reality, like sunglasses shading and constituting our view. According to Kant, man is stuck within the categories of his own mind, and unable to know reality in itself, or what he called the “noumenal” realm. One consequence of this was that the traditional notion of “truth,” as the mind’s conformity with reality, was dismissed as naive conservatism. According to Balthasar, two main traditions in biblical studies developed after Kant. On the one hand, many Enlightenment thinkers (such as H.S. Reimarus, d. 1768) rejected the Church’s dogmatic positions as a mere arbitrary imposition of power, thus beginning the quest for the “historical Jesus”—a quest which often ended with a Jesus who expressed their own biases and philosophical presuppositions. To such a position, Balthasar argues:

In spite of isolated precursors, such as Richard Simon, historical Biblical research was predominantly a child of the non-believing Enlightenment (Reimarus, Lessing), which directed its theses polemically against an uncritical belief in the Bible. They undertook to remove the layers that faith had painted over, so as to expose beneath them the authentic historical figure of Jesus. The “historical Jesus” thus exposed presented the most varied faces, all of which more or less corresponded to modern expectations or ideals. 4

The other hermeneutical tradition, represented by a leading Lutheran scholar, Rudolf Bultmann, (d. 1976), retreated into the subjectivity of a personal faith, thereby removing Jesus Christ from the category of historical truth (and thus inquiry) and making personal experience the sole criterion for judgment. Balthasar describes how Bultmann’s methodology ultimately hindered Protestant theology by severing the link between the Incarnation, faith, and the Church’s mission to evangelize:

In Kantian fashion, Bultmann prepares for faith a path whereby it criticizes and limits itself and, thus, admits its inability to come to see the object of faith, namely, an “historical Christ.” The dualism that thus arises between history (Historie) and contemporaneity (Geschichte) is truly tragic. First, it is tragic for theology itself, which is now coming close to giving up altogether the fact of God’s Incarnation: henceforth theology can be founded only on the sole absolute remaining to it, namely, faith’s self-understanding. And this dualism is also tragic for the Church’s proclamation and mission, which cannot interpret such retrogression other than as an act of self-forsaking on the part of Christianity. 5

Balthasar’s approach also attacks modernity’s enthronement of mechanics, and the loss of aesthetics. If one person’s innate categories shape the way he sees the world, and if another person happens to see things differently, there is no way to prove who is right or wrong, especially in regard to values that are not empirically verifiable, such as beauty. Balthasar describes the subsequent split between fact and value as a cold and desperate marriage with matter that eventually destroys all beauty and love:

The world, formerly penetrated by God’s light, (beauty) now becomes but an appearance and a dream—the Romantic vision—and soon thereafter nothing but music. But where the cloud disperses, naked matter remains as an indigestible symbol of fear and anguish. Since nothing else remains, and yet something must be embraced, 20th century man is urged to enter this impossible marriage with matter, a union which finally spoils all man’s taste for love. But man cannot bear to live with the object of his impotence, that which remains permanently unmastered. He must either deny it or conceal it in the silence of death. 6

With matter perceived as the only “reality” and science as the judge, jury, and executioner of all other disciplines, Balthasar’s project is key because it articulates how the experience of beauty overcomes the Kantian dualism and the fact/value divide.

Balthasar and Beauty

Key to Balthasar’s response to modern biblical studies is his concept of beauty. For Balthasar, beauty “dances as an uncontained splendor around the double constellation of the true and the good.” 7 Following St. Thomas, who defined beauty as “that whose very apprehension pleases” or “that which pleases when seen,” 8 Balthasar links beauty to human perception, and the way human beings gain knowledge. Following Aristotle, Thomas and Balthasar agree that human knowledge is mediated by sensation, but sensible appearance does not exhaust the scope of known reality. In other words, sensory images express a “deeper” ground of reality, a reality which, while being exposed by an outward appearance, nevertheless remains somewhat invisible and mysterious. In a paragraph worth quoting at length, Dr. Michael Waldstein skillfully describes this inner and outer experience of reality using the example of meeting a human person:

Essential being, the really real, lies in a sense “behind” sensible appearances. However, this substantial reality does not become manifest immediately. For example, I cannot grasp other persons immediately, but I perceive first of all their appearance. Still, even though inner reality is not immediately accessible, it manifests itself in and through the outer. I can grasp other persons in their appearance. Such manifestation implies that the outer, sensible appearance has significance, that it is filled with a meaning that comes from within. Or, seen from the other side, such manifestation demands that the inner does not merely rest in itself, but expresses itself in the outer. The interior, which as such does not lie manifestly before our perception, is brought forward in such a way that it can be perceived. It is not only somewhat signalized, but it is translated into something seen. In this way one can say to someone “I see you.” 9

The aspect of an inner reality that communicates itself through an external medium is central to Balthasar’s account of beauty. Using terms closely linked to the Thomistic concepts of splendor and harmony, Balthasar uses the terms “ground” and “form” (or “Gestalt” in German) to describe the inner reality expressed, and the outward manner of expression. From this foundation, one who encounters beauty experiences a hidden, deeper reality which expresses itself through a unified and pleasing appearance. “Gestalt refers to a being from the point of view of its outer medium of expression, inasmuch as this manifold medium is united, beyond itself, by the expression of an inner depth.” 10

While recognizing that beauty is seeing something pleasing, the recognition of beauty is not automatic. Beauty is not simply anything that pleases, but an encounter with an invisible reality that remains veiled in mystery, even as it expresses itself externally. Due to the variety of expressions something may express, many may not recognize beauty when they fail to see the whole medium of expression. In other words, many fail to see beauty because they fail to see the unity of the Gestalt. Only a “big picture” approach can see beauty, for Balthasar. One problem with modern historical studies is that it often divides up a Gestalt with an atomistic conception of nature, moving from the parts to the whole, instead of viewing the parts as united by a higher principle, by the whole. Balthasar, therefore, believes that the central problem with modern Scripture studies is its atomistic understanding and perception of reality, which comes from being fettered by Kantian formalism:

This tragic dialectic, into which Protestant theology has largely fallen, lacks exactly the same thing as the rationalistic school of Catholic apologetics: namely, the dimension of aesthetic contemplation. The figure which confronts us in Holy Scripture is more and more dissected in “historical-critical” fashion until all that is left of what was once a living organism is a dead heap of flesh, blood, and bones. In the field of theology, this means, at every step, the same inability to perceive form which a mechanistic biology and psychology reveal with regard to the unitive phenomenon of a living being. Nothing expresses more unequivocally the profound failure of these theologies than their deeply anguished, joyless, and cheerless tone: torn between knowing and believing, they are no longer able to see anything, nor can they, therefore, be convincing in any visible way. Both tendencies remain fettered by Kantian formalism, for which nothing exists but the “material” of the senses which is then ordered and assimilated by categorical forms or by ideas. 11

Going back to the modern divide between “subject” and “object,” Balthasar attacks both the historical-critical method’s philosophical presuppositions (that our ideas order reality) and their method of inquiry (focusing on “dead” matter without seeing the unity of expression throughout the whole Gestalt). Balthasar is at great pains to affirm that objects act on us, and reveal their inner reality through this expression. One way he illustrates the correct manner of perceiving reality that overcomes the Kantian divide is by appealing to an early Christian Christmas hymn which describes how the visible Christ reveals the invisible God:

Because through the mystery of the incarnate Word, the new light of your brightness has shone onto the eyes of our mind, so that, while knowing God visibly, we are snatched up (seeing Christ incarnate) into the love of invisible things. 12

The Incarnation is obviously in a unique category since the Son expresses the Father while being a separate person who shares his nature. The union between expression and reality expressed, between Gestalt and Ground, transcends the union between expression and ground of creaturely beings. The union between the Son’s Gestalt and the Father as Ground is both more unified (they share the same nature) and more distant (the Son reveals another person, unlike created being, which reveals its own inner depth). For Balthasar, the Christmas hymn reveals the “rapturing” experience characteristic of all beauty, created or uncreated. According to Balthasar’s (and Aquinas’) understanding of beauty, one who sees beauty is raptured to a knowledge and love of reality that transcends what is merely visible. This overcomes the Kantian divide because it affirms the unity of ground and expression while not equating the two. One who perceives a Gestalt, also perceives the invisible reality which it expresses. However, as we mentioned above, the recognition is not automatic, and the disposition of the beholder is crucial for correctly perceiving beauty, something especially important for biblical studies.

Balthasar and Biblical Studies: Mother Mary as Model

According to Balthasar, modern biblical studies are hampered by philosophical presuppositions. He believes that the modern historical-critical method is hampered by the Kantian divide between the subject and reality, and an atomistic approach. Such an approach leads it to miss the entirety of Gestalt, dissecting its expression into individual parts without reflecting on the whole which unites them, and which reveals its hidden depth or ground. Applying his theory of beauty to biblical studies reveals the genius of his approach. He begins by stating that apologetics (or fundamental theology) is primarily the task of articulating the coherent unity of Christ’s Gestalt, showing how Christ’s words and actions, presented in Scripture, reveal a common and believable personality. Rather than arguing that Christ’s miracles and deeds “prove” or “argue” for his divinity, Balthasar believes that simply getting one to “see” Christ is good enough; that Christ’s Gestaltor form, has enough power to convert or “rapture” one to a faith (or knowledge) of his divinity and mission from the Father. The problem with modern historical-critical studies is that they refuse to see; they simply look past Christ, constructing “screens” which hamper their vision:

Looking past Christ, failing to see him, is something that can occur in various ways, but all these ways have this in common, that the gaze cannot withstand looking at the form of Christ himself. It is impossible to look into his eyes and maintain that one does not see him. There is, first of all, the possibility of erecting a screen before his image, and then being convinced, or convincing oneself, that it cannot be removed. A modern example of this is the “historical-critical method,” which supposedly can go only as far as the testimonies of faith in Christ, and which then sees these testimonies as a screen hiding the historical Jesus. Or one can place before the image all sorts of historico-religious schemas (such as the myths of the “salvation-bearer”), or simply a system of categories under which one assumes, perhaps in good faith, that the phenomenon will be subsumed. For very many who refuse to take a look for themselves (but, astoundingly, also for many an earnest seeker), the screen of the Church “as it unfortunately happens to be” suffices for them to excuse themselves from looking at Christ. 13

According to Balthasar, the problem with the historical-critical method is that they fail to see the whole Christ by determining ahead of time what they will see. Their philosophical presuppositions hinder them from encountering a person who emerges from an open, humble reading of Scripture. While historical studies are necessary, Balthasar affirms—Christ is indeed a real historical figure—they must never hinder one from seeing the total person that emerges. For according to Balthasar, a figure does indeed emerge which “speaks” to the reader inviting him to faith. Scripture invites a humble reader to “see” the invisible reality expressed in the words, and recognize the human appearance of one who lived 2000 years ago in Palestine—to see God. The reason why Christ’s Gestalt is hidden and does not overpower one, forcing one to recognize its divinity, Balthasar attributes to the logic of divine love. Christ’s Gestalt is coherent and persuasive because it wields the power of love, a love which emptied itself and died an agonizing death on the cross. This love is the evidential power of Christ, and it forces a response from the reader: either to accept his love, or to reject it. Thus, the mystery of Christ is that the one who sees him, who adequately experiences his Gestalt, is raptured to an encounter with the invisible God, and transformed into his image.

There are two extremes which Balthasar is balancing, and they respond, as we have mentioned, to the nature of human perception. On the one hand, the Gestalt of Christ, while truly mediating the invisible God, does not force itself on anyone, and can be missed, ignored, or rejected. This is due to the fact that humanity has free will and experiences reality through the senses; he can either receive, reject, misjudge, or look past another person; even if that person is God. On the other hand, Christ’s Gestalt is grounded in the eternal God, and possesses real power to mediate faith/knowledge/vision of the invisible God. Without the grace of God, no one could come to see Christ’s Gestalt, Balthasar says.

From what has been said, it becomes clear why Balthasar views Mary as the model of biblical interpretation. Mary’s open and humble demeanor is the model for all who approach sacred Scripture, because—instead of proudly determining beforehand what type of evidence will be accepted, or what constitutes reality—Mary humbly accepts God’s revelation, and ponders it in her heart. Accepting God’s revelation, she ponders and responds to God, testifying to what he has done for her, and making his Gestalt visible to others. By carrying God’s Word within her, and making it visible to the world, Mary is transformed into Christ, carrying out his mission of making God present in the world. Her humble, thoughtful, and transforming encounter with God’s Word (and sacraments) therefore, makes her the model of biblical interpretation for Balthasar. All scholars, he says, are called to be open to Christ’s Gestalt, present in Scripture, so that they may truly “see” it for what it is: Divine Love incarnate. With the aid of Grace, scholars who approach Scripture should ponder the form of Christ as it appears on the page, and allow that figure to come to life, so to speak, by listening, pondering, and explaining it to others. They must show the coherency of Christ’s Gestalt by articulating the divine love which unites it, and which invites others to share in it.

In conclusion, Balthasar responds to the crisis in modern biblical interpretation by appealing to beauty. In analyzing the way we perceive reality and experience beauty, he overcomes the Kantian divide between subject and object by appealing to the experience of rapture, which allows one to experience and know an inner, invisible, mysterious reality through its outward expressions. Mary is the model because she is humble and open to receive reality and God. She does not set “screens” over her vision—such as philosophical presuppositions that determine the extent of her knowledge, nor view reality with an atomistic focus that misses the unity and wholeness of what is in front of her. Instead, Mary’s vision is clear: she sees the invisible reality through its physical expression. She ponders in her heart what she sees, and is raptured by grace to a knowledge and love of the invisible God, now made visible in Christ. By fixing her eyes on the loving gaze of Christ, she is drawn up, and transformed into, that same love, making it present to others. She becomes another Gestalt of Christ, incarnating his love in her own body, and drawing others to him, inviting them to “see” and share in the love which created the world.

- Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, O.P. “Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Contribution to Ecumenism,” in Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Works, edited by edited by David Schindler. Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1991; 252. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, “Homily at the Funeral Liturgy of Hans Urs von Balthasar,” in Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Works. Edited by David Schindler. Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1991; 295. See also the message Pope Benedict XVI sent to the participants of the International Convention on the occasion of the Centenary of the birth of Balthasar. “The example that von Balthasar has given us is, rather, that of a true theologian who in contemplation had discovered a consistent course of action for giving Christian witness in the world. We remember him on this important occasion as a man of faith, a priest who, in obedience and in a hidden life, never sought personal approval, but rather in the true Ignatian spirit always desired the greater glory of God. With these sentiments, I encourage all of you to continue, with interest and enthusiasm, your study of the writings of von Balthasar and to find ways of applying them practically and effectively.” Vatican City, October 6, 2005. Read the full text at:http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/messages/pont-messages/2005/documents/hf_ben-xvi_mes_20051006_von-balthasar_en.html ↩

- John Paul II in a telegram at the death of Balthasar on June 30, 1988; see Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Work, Ignatius Press: San Francisco, 1991 ↩

- von Balthasar, H. U. (2009). The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics I: Seeing the Form (E. Leiva-Merikakis, Trans.) (518–519). San Francisco; New York: Ignatius Press; Crossroads Publications. ↩

- Ibid. (519). ↩

- Ibid. (18-19). ↩

- Ibid. (18). ↩

- ST, I-II, 27, ad 3. ↩

- Dr. Michael Waldstein, “A Manuductio From St. Thomas to Balthasar on Beauty,” Ave Maria University, Spring 2012. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, 168-169 ↩

- My translation from Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, 117: Quia per incarnati Verbi mysterium nova mentis nostrae oculis lux tuae claritatis infulsit: ut dum visibiliter Deum cognoscimus, per hunc in invisibilium amorem rapiamur. ↩

- Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, 500-501. ↩

Luke Murray the world we live in is much more complex than the philosophical world that Balthasar seems to be addressing. The philosophical landscape is made up of philosophies from every part of the world. My own Catholic Parish in Detroit Michigan represents peoples from all parts of the world. So to make assumptions about Modern Biblical Studies based on the influence of Kant definitely overstates his influence. Your essay assumes an either or perspective that certainly does not ring true in my experience. Taking into consideration the critical views of other critics of modern Biblical historical criticism, I would say there are definitely dangers and certainly advantages to what Kant contributed to philosophical discourse.

Very well done, so insightful!!

Tom,

Thank you for your comment. I agree that the term ‘Modern Biblical Studies’ is very broad and includes a wide variety of philosophical positions. I am using the term loosely to describe the approach to biblical interpretation that one often finds in academia today. I surely do not want to give the impression of condemning all modern scripture studies or simplifying modern philosophy down to Kant. Balthasar spends literally thousands of pages discussing the philosophers and theologians who have changed the way we view the world. Due to size constraints, I have tried to summarize the key aspects of his thought that relate to biblical interpretation. This does run the risk of oversimplifying the matter, of course, so I would encourage those interested to read Balthasar himself.

Interesting and helpful piece. Von Balthasar also did seem to realize that beauty was related quite directly to the facticity of the New Testament narrative: it isn’t just beautiful but also true. In this regard, he told George Kelly he thought his book “The New Biblical Theorists” was the best ting he had done. Given the book is highly critical of Raymond E. Borwn, that comment seems like a very direct revealing of his opinions on the zeitgeist.

Thank you Mr. Murray for this excellent paper showing the absurdity of Kant and the logic of Urs. Studying the Scripture requires as I have had, expert professors, such as Fathers Daniel martin CM, Joseph Lilly and Bruce Vawter Cm who gave and exegeted all of the Scripture using the transcendental way of one true good and beautiful revealing the Holy Spirit who allows one to believe The historical person of Jesus and other persons of His time, the apostles, the romans, and the Mother of God Mary