The Lord has given us desires, and wants to fulfill them, with his care, and with his peace; he wants us to flourish in knowing him, and directing all endeavors and expectations to him.

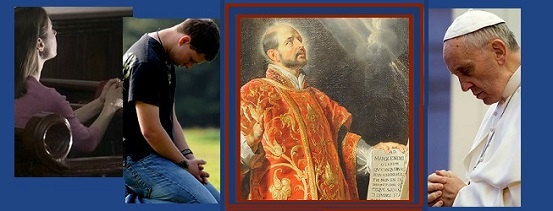

St. Ignatius of Loyola knew, better than most, of the human capacity for self-deception. He was a former knight, was arrested a few times, was involved in many a bar brawl, and alluded to having committed just about every crime imaginable. The slow-to-convert Ignatius discovered in his own life, and eventually for all of us, who we most truly are. From his conversion experience, he stressed praying out of one’s deepest desires, to enter into conversation with the Spirit of God, in seeking what it is that “I most truly want.” For example, at the start of each of the prayer periods of his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius requests that the one making the retreat, should: “Ask for the grace I now seek…” Intriguing isn’t it? Why should I ask for what I want? Don’t I already know what I want? Doesn’t God already know what I want? How is the absolute creator of all swayed by my needs and my requests?

Ignatius’ argument behind this way of prayerful boldness is that we humans are creatures into whom our loving God has implanted divine desires; that we are made to long for God, and he alone can satisfy our hearts. It also reminds us that we are not computerized automata, but have desires of our own, as well as the ability to enter into loving collaboration with the Maker of us all. Yet, as wayward children, we have let our holiest desires be clouded by our skewed and, oftentimes, selfish expectations, by our more immediate needs, and by our desires for popularity and recognition, for physical allure and material comforts. We can have conflicting desires, like St. Augustine’s famous prayer early on in his life, “Grant me chastity, O Lord, but not yet!” But, the divided heart will never be happy, for it will never get what it wants. The secret, then, is to go further, cast into the deep, and allow ourselves to discover our deepest, holiest desires. In order to do this, Ignatius has us settle quietly into what it is we most deeply seek. Once quieted, we hear the voice of the Spirit, “deep calling unto deep,” as the Psalmist expresses it. However, to know our deepest desires, and not just our superficial wants, we need to be brought into union with the creator of our desires.

The desires within us, which everyone has, have been learned through other people with whom we spend time. We all live in families, in social structures, in communities, and in circles where some things are valued over others; where some items, and ways of life, are presented to us as more attractive, more desirable than others. We are not the self-made people we think we are; each of us is a collection of learned desires and traits. Especially as Americans, we pride ourselves on being “self-made,” self-developed beings who discover who we most truly are. Like Prometheus standing up to the gods in autonomous rebellion, each of us makes our own way in life. Ignatius would see this differently: we are given our identity, each of us has been named, we have been brought into God’s family through baptism, we have learned—rightly or wrongly—a particular way of life, and so on. Whereas we tend to glorify our autonomy, Ignatius would always have us see our truest selves as relational, crying out for community and love. The deepest desire of every human heart is to be known, to be loved, and to love forever.

We all learn early on, however, that true love is elusive, and that relationships can be risky. We, instead, have all learned how to hide behind the mask of self-sufficiency. Like H.G. Wells’ Invisible Man, we hide our empty selves with the bandages of success and wealth, achievement and power. We are afraid to let anyone encounter the self we all know is just under the surface, so we wrap that invisible presence around with illusory accomplishments, status, and gossip. We tend to blame others for our shortcomings, afraid to look too directly at our own brokenness. So instead, we cover up our hearts with little luxuries and distractions, anything to keep ourselves, and others, from seeing who we really are. We may show only bandages to the world, but they’re better than nothing.

To overcome this attachment to our illusory self, Ignatius would advise us to do two things: first, recognize that only union with God is going to satiate and satisfy our deepest longings; and, second, see how union with God, in his becoming human, can now be approached through that humanity, Christ Jesus—the Way leading to God the Father. The Ignatian approach is never, therefore, a “God-and-me” solitary affair, and it is never a spirituality that is going to insist on “God alone.” It is a spirituality that always incarnates and, therefore, leads us back into the world. As baptized members of the body of Christ, we are to recognize that our God is now human, now in space and time, a God who, through our Mother Mary, has gotten so close, as to become one of us. God is no longer simply “out there,” God surrounds us. We are called, therefore, to find God in all things! To allow God to “fit” into our daily experience, we must let our souls be magnified. This is why Ignatius linked desires with the spiritual gift of magnanimity, large-souled-ness. Only the large-souled person will be “big” enough to live above all rancor and jealousy, to live in union by the Spirit, and no longer with his or her own petty littleness.

Not too long ago, Pope Francis showed his Ignatian spirituality by preaching on this very point. The Holy Father said:

The Christian is magnanimous; he or she cannot be timorous: the Christian is magnanimous. And magnanimity is the virtue of breath, the virtue of always going forward, but with a spirit full of the Holy Spirit. Joy is a grace that we ask of the Lord. These days—in a special way, because the Church is invited—the Church invites us to ask for the joy, and also the desire—that which propels the Christian’s life forward is desire. The greater your desire, the greater your joy will be. The Christian is a man, is a woman, of desire—always desire more on the path of life. We ask the Lord for this grace, this gift of the Spirit: Christian joy. Far from sorrow, far from simple fun … it is something else. It is a grace we must seek.

The Lord has given us desires, and wants to fulfill them, with his care, and with his peace; he wants us to flourish in knowing him, and directing all endeavors and expectations to him.

Many of us are afraid to trust our hearts, and for this we need to ask the Holy Spirit to teach us. Many of us still have a “default position” of God: one who is not interested in our day-to-day experiences, but who rejoices when we offer him only our pious deeds, or painful sacrifices. Many of us can live as quasi-Buddhists, who think we must efface ourselves, and so remove all of our heart’s desires. But I wonder if this summer, we might not slow down a bit, and look at the faces across the table, hear the voices in the yard, smell the barbeque, and taste the fresh fruits, and thank our God for having made us the way he did—with all of our experiences, loves, family, and friends. This is what Christianity is all about: recognizing the God of love, made incarnate in the very human and concrete circumstances of life on this earth. This is what the tradition of our Church teaches: “Find your delight in the Lord who will grant you your heart’s desires” (Ps 37:4).

Thank you, Father Meconi, for this wonderfull look at some of the Spiritual Excercises ” of St. Ignatius . WE are shown the way to avoid grave sin from it. Constant killing of the innocent , constant stealing, constant bribery, cheating continuing in many countries can cease if a person like that would turn to God and Jesus Christ and ask for this Divine help. If these kinds of persons could read the ” Spiritual Excercises ” maybe it would help them to live the Good life..

At the same time, I think we need to remember that the point of the Spiritual Exercises is to attain “indifference” to all things, except insofar as they help us attain our purpose: to praise, reverence, and serve God our Lord and by this means to save our souls. See also Hans Urs von Balthasar, Homo creatus est, Explorations in Theology / vol. 5 (Ignatius Press).

But I don’t think it’s “either/or” is it? I mean, my understanding is that a basic paradigm of the Exercises isn’t either we attain ‘indifference’ or we recognize/enjoy the love of God made incarnate around us.

It seems like indifference is just the path to leads to a greater recognition & trust &, therefore, a greater enjoyment. This clumsily stated way of life is evident in stunning simplicity in the lives of the 3-6 year olds who attend our Catechesis of the Good Shepherd. Their inherent orientation is to wonder & enjoyment of the most simple parables. It’s their unquestioning trust that leads to their ‘indifference’, which they’re not worried about ‘attaining’. I learn so much from them!

My point, regarding the article, is that indifference would seem to be the first priority in the Exercises, rather than our desires. . .

Thanks for this conversation. As any Jesuit realizes, Ignatius’ “indiferencia” is not an easy term to translate. We are neither Stoics nor Buddhists who try to find God in squelching all their own personal desires. Ignatius realized deeply that it is God who plants the desires of our heart firmly within us. To be indifferent in the truest Ignatian sense, then, is to be “receptive” to all God wants to do with a soul–to go where he wants and to do what he wants. To be indifferent is far from being apathetic or resigned to one’s own heart or the condition in which one finds oneself. To be indifferent for Ignatius is to allow oneself to be moved by God as a beloved and trusting friend, willing to be open to the movements of God above all.

Agreed! But isn’t St. Igntius’ intent (per von Balthasar) that we desire what God desires, that we choose what God chooses?