The purpose of this one Church is to bring about the supernatural communion of all humanity together in the Spirit, under Christ as head, giving praise to the Father.

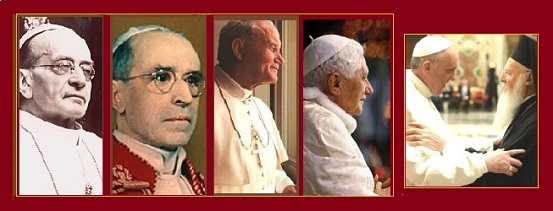

Popes Pius XI, Pius XII, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis embracing Patriarch Bartholomew.

This article aims to accomplish two things. First, it presents a Catholic vision of ecumenism based upon an ecclesiology consonant with the Catholic Magisterium. Second, it highlights three stages of the Catholic Church’s involvement in the ecumenical movement, linking each stage with one of the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. It calls, in the end, for an integration of these three virtues in the development of an ecumenism that is uncompromising in principles, ardently hopeful of reaching the goal of full visible communion through God’s grace, and suffused with charity in listening to the other, benefiting from him, and impelling both self and other—without that distortion of pressuring which is called “proselytism”—towards true union with the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Spirit.

Ecumenism in Catholic Ecclesiology

As the Catholic tradition teaches, misreadings of Vatican II, which has existed in its fullness since Pentecost, and will remain intact until the end of this age. The purpose of this one Church is to bring about the supernatural communion of all humanity together in the Spirit, under Christ as head, giving praise to the Father. This purpose is not identical with the very essence of the Church on earth, since, on earth, the Church embraces venial and mortal sinners. Although called by God and, thus, wooed by him, the mortal sinner does not exist in a living communion with God. A real member of the Church, a Catholic mortal sinner is, nevertheless, dead unto God. Further, even those who by God’s grace achieve great holiness on earth have a threefold longing: They groan for the redemption of their bodies (Rom 8: 23); they cry with Paul to be delivered from concupiscence, that “body of death” (Rom 7:24) that lies in wait for them (Gen 4:7); and they long to depart and be with Christ (Phil 1:23). Notwithstanding, these deficiencies in her members, the very Church Jesus founded does exist, in its fullness, on earth.

This Church of Christ is endowed with a threefold gift: The full deposit of faith, all the means of sanctification, and a hierarchical structure. To this threefold gift there corresponds a threefold requirement for incorporation into this Church: profession of the entire faith, acceptance of all the means of sanctification, and communion with the hierarchy. Contrary to misreadings of Vatican II, incorporation does not admit of degrees, although “communion” with the Church may admit of degrees. Incorporation is a juridical matter the end of which is spiritual communion. One is either “incorporated” or not, but, depending upon one’s situation, one may be more or less in touch with the supernatural goods that are the center of the Church’s life. 1

This one Church of Christ, which as Catholic tradition constantly affirms is none other than the Catholic Church, does not preclude but fosters authentic diversity. 2 One way in which she fosters diversity is in her constitution: She is constituted not simply at a universal level, but also at a local level. The universal Church—though ontologically and temporally prior to the particular church—can enjoy a legitimate diversity of expression in a special way through her particular churches. A particular church of the Catholic Church is a communion of believers gathered under a validly ordained bishop who is hierarchically united to the Bishop of Rome, Pope of the Entire Church. Now, each believer in a particular church contributes gifts to the whole gathering in unique ways, for there are teachers, laborers, intercessors, musicians, leaders, those who suffer, fathers, mothers, children, etc. Similarly, every particular church can contribute unique gifts to the Church universal. These contributions—both individual and collectively enjoyed–come both from gifts of natural endowment or skill (Lumen gentium {LG}, art. 13) and also from charismatic gifts. 3 These gifts make possible different, but totally compatible, expressions of the one saving mystery. None of these unique gifts adds anything to the intensive plenitude of the Church, which is constituted by hierarchical unity, and by the fullness of truth, and sanctifying rites. In other words, the Church is the Church—her essence in tact—with or without these gifts. Notwithstanding, these gifts do add to the Church’s extensive reach and expressive power. Theological works, hymns, ministerial services, etc., are wonderfully unique from age to age, from church to church. Further, groups of particular churches can together offer a collective gift, such as a beautiful and unique liturgical rite, or theological tradition, etc. Finally, although one simply must maintain that the Church’s essence does not change through the changing vicissitudes of her members and of history, yet one must not think that the “abstract essence” of the Church subsists qua abstract. Indeed, the Church has existed on earth only concretely. And the very “way” she exists can be better or worse; she can be healthy or sick. And this sickness and health depends upon the degree to which, and manner in which, her members embrace her mission, and believe, and disciple her Lord. On the basis of this brief sketch, I can describe the task of Catholic ecumenism.

Catholic ecumenism is the manifold effort to establish full communion among all Christians, not one by one, but corporately, considering each church or ecclesial communion as a whole. In this respect, ecumenism differs from—and yet is complementary to—the wonderful effort of Catholics to reach individuals one at a time (Unitatis redintegratio {UR}, art. 4). Concretely, Catholic ecumenism has as its goal nothing short of incorporating all non-Catholic Christian churches and ecclesial communions into the Catholic Church. 4 This incorporation will be realized by confession of the same faith, acceptance of all the sacraments, and communion with the Catholic hierarchy under the Pope as head.

The hope of Catholic ecumenism is to restore to its fullness whichever of these three elements a non-Catholic church or ecclesial communion only partially possesses. Since ecclesial plenitude has been entrusted to the Catholic Church alone, restoration of the fullness of these elements in non-Catholic communions is the unique gift the Catholic Church has to offer. This restoration is, therefore, her unique mandate. Now, each non-Catholic church and ecclesial communion—insofar as it enjoys a legitimate but unique way of expressing or celebrating the one faith—can contribute gifts to the universal Church. Hence, ecumenism results in a marvelous “exchange of gifts” (LG, art. 13; Ut unum sint {UUS}, art. 28), to the glory of God. There have been roughly three distinctive phases in the Catholic approach towards ecumenism, and we look forward to a balanced fourth stage.

Stages in the Movement

The first stage of the movement of ecumenism has, as its most recent advocates, Popes Leo XIII (Satis cognitum, art. 16 {SC}) and Pius XI (Mortalium animos, arts. 10–11 {MA}). Read from a contemporary perspective, SC and MA showed little enthusiasm for ecumenism. The relative lack of enthusiasm can be attributed largely to the deplorable state of efforts at inter-confessional harmony of those times. MA faced an ecumenical movement that was rather anti-doctrinal and relativistic. Still, neither encyclical condemned genuine ecumenism. Nor is either irrelevant. Indeed, SC and MA point to the fundamental and irrevocable Catholic starting point for ecumenical dialogue, namely, strict adherence to the fullness of the truth. Pius XI sensed an urgent need in his day, to emphasize an uncompromising stance in favor of truth. The encyclical warns against a false irenicism that disguises itself as charity (MA, art. 3). Pius’ praiseworthy defense of the fullness of the truth, his refusal to allow the faith to be divided into two departments—those that are indispensable and those that are dispensable (MA, art. 13)—attests that his contribution to the movement is firmly grounded in the theological virtue of faith.

To adhere to Pius’s teaching, and to do so with joy, is therefore not an act of triumphalism. Rather, it is humble gratitude for, and submission to, the truth. Some may be tempted to hide Pius’ words as though beneath a bushel, either because they seem too bright for dim eyes, or because they seem tantamount to “ecclesiological arrogance.”

Yet, to hide Pius’ words for these reasons risks infidelity on the one hand, and Pelagianism on the other hand. As to the former, St. Paul teaches us, “If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to that which you received, let him be accursed” (Gal 1:9). As to the latter, the deposit of faith is—as is the making a man into a son of God (Jn 1:13)—no work of man. Rather, “This is the Lord’s doing; it is marvelous in our eyes” (Ps 118:23; Mt 16:17). To be abashed that the Catholic Church is blessed with the fullness of truth, and is the only one true religion, as though this were due to human merit, is to neglect its character as gift. Pope Pius XI, then, teaches the virtue of faith: both as to that which we believe (fides quae) and as to the witness (the Church) whose word we trust (mediation of the fides qua).

The Second Vatican Council, in turn, marks the dawn of great and courageous hope, a hope that the return of all Christian churches and communions to the Catholic Church is, by God’s grace, a concretely real possibility. To this hope corresponds a grave and irrevocable duty for Catholics: the mandate to enter the ecumenical movement. So, the Second Vatican Council is marked by theological hope. God is good and powerful enough to accomplish what the sins of Catholics and other Christians hinders, namely, the fulfillment for non-Catholics of Jesus’ prayer “that they may all be one” (Jn 17:21). Lack of this fulfillment also impairs the Church as she seeks to live out her essence of communion, and to exercise her mission among men. Thus, this prayer is also a prayer for the Catholic Church in her lived life.

At this point, we must countenance an understandable difficulty many people, especially some Catholics, perceive: The hope of Vatican II, so some maintain or worry, seems to be contrary to the faith of Pius XI. This apparent tension is used by some to justify what Benedict XVI calls the “hermeneutic of rupture.” 5 As this hermeneutic alleges, Vatican II contradicts the past. As Pope Benedict astutely recognizes, both progressive and arch-traditionalist interpreters of Vatican II share this hermeneutic of rupture. Progressives cling to what they think is the “spirit” of Vatican II, and reject the past; arch-traditionalists cling to what they think is the past, and reject Vatican II. Contrary to both groups, contrary to this hermeneutic of rupture, is the hermeneutic of reform and dynamic continuity, an approach suggested by the Council itself: “Following … in the footsteps of the Councils of Trent and Vatican I” (Dei verbum, art. 1). In all truth, Vatican II does not alter Catholic teaching: Jesus’ prayer is already fully realized (as to ecclesial plenitude) in the Catholic Church. Thanks to the recent clarification in “Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church,” Catholics can readily reject those ecclesiologies that differentiate the Church of Christ, and the Catholic Church. 6 Moreover, Catholics can perceive continuity between the Tradition and the teachings of Vatican II, where the “magisterium of theologians” erroneously found only rupture.

Still, Vatican II rightly urges Catholics to “press on,” working so as to remove the obstacles to full communion that on the one hand affect non-Catholic communions and that, on the other hand, hinder the Catholic Church as she works to foster ecclesial plenitude in these communions, and as she works to express the mystery of Jesus more fully through them (UR, art. 4). This ecumenical activity—to be accomplished through prayer, dialogue, charitable cooperation, and interior reformation (conversion of hearts and renewal of ecclesial practices)—is rooted in what Christians have in common: One Lord, a common body of faith, and one baptism. Vatican II stresses this common good: “Many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside the visible confines of the Catholic Church” (LG, art. 8). Since what is common is the basis for progress, Catholic ecumenical activity is not violent and extrinsic. The activity accords with the connatural dynamism of these gifts shared in common. Why, these gifts are by the Holy Spirit oriented towards Catholic fullness: “Since these are gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, they are forces impelling towards Catholic unity” (LG, art. 8). What is most wonderful, these very gifts are even conducive to salvation (UR, art. 3).

In short, non-Catholic churches and communions already participate (have a partial share) in the grace and truth that, in its fullness, is entrusted to the Catholic Church alone (LG, art. 8; UR arts. 3 and 4). That is, these communions participate in certain goods proper to the Catholic Church, even though they do not fall within her visible boundaries. All Christians already enjoy a share in Christ and in ecclesial communion together (1 Cor 10:16). The Catholic ecumenical goal is to foster the realization of the “not yet” of the deficiencies in this or that communion. Without genuine hope, no one can bear this heavy burden. Vatican II thus urges us toward an active hope. Yet, if this burden is to be light, and if the yoke is to be easy (Mt 11:30), the movement must be quickened by the noblest effect of the Holy Spirit, the greatest of the theological gifts, namely, charity, which draws all men to God, and to one another. Charity is, as it were, the created soul of the Church’s life (as Charles Cardinal Journet put it so well).

The Pontificates of John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis manifest the theological virtue of charity in unparalleled ways. John Paul’s very life was a witness, not just to hope, but also to charity. In unprecedented fashion, he implored forgiveness for the sins of individual Catholics against members of other churches and religions. He initiated dialogues across the globe. He was enthused wherever he found truth and beauty, holding it fast (Phil 4:8). His encyclical, Ut unum sint, attends to the witness of the martyrs, Catholic and non-Catholic, who died in charity (UUS, art. 1). Following the footsteps of Vatican II, he states, “The commitment to ecumenism must be based upon the conversion of hearts and upon prayer” (UUS, art. 2). 7 Prayer is, as Vatican II teaches and as John Paul reaffirms, the “soul” of the ecumenical movement (UR, art. 8; UUS, art. 21). It is through prayer that the love of God shall be poured forth into our hearts (Rom 5:5), binding us to God, and urging us to an ever-deeper communion with one another (Jn 15:9–12).

John Paul turns our attention to charity as the source of prayer. If prayer is the soul of ecumenism, and if charity is the motive for prayer, then charity is the driving force of ecumenism: “This is truly the cornerstone of all prayer: the total and unconditional offering of one’s life to the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Spirit” (UUS, art. 27). Without compromising fidelity to the full deposit of faith (UUS, arts. 18–19), Catholics must, John Paul contends, strive mightily in charity to realize, before the eschaton, the full force of Christ’s priestly prayer. Through an “exchange of gifts” (UUS, art. 28) every partner in dialogue stands to gain, each in its own way, and each partner can contribute something for the good of the whole.

Following in the steps of his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, in his encyclical, Deus caritas est, has indelibly marked his pontificate chiefly by the virtue of charity. Charity is the communion of man with God, and of man with man. Thus, charity names the essence of the Church in heaven, and the telos of the Church on earth, which already enjoys, incipiently and in hope, the holiness of divine charity.

Pope Benedict shows, with his genius for a fresh manner of presenting the ancient truths, that fidelity to the Church, fidelity to Jesus, demands that one share all that one is, all that the Church is, with one’s neighbor, one’s friend:

I cannot possess Christ just for myself; I can belong to him only in union with all those who have become, or who will become, his own. Communion draws me out of myself towards him, and thus also towards unity with all Christians. We become “one body,” completely joined in a single existence. Love of God and love of {neighbor} are now truly united: God incarnate draws us all to himself. (Deus caritas est, art. 14)

Pope Benedict’s stress on charity is coupled with his clear affirmation of certain truths of which some Catholics seem to have forgotten. One sees this, for instance, in the statements of the CDF under his pontificate. RSQ shows the firm continuity between the teaching of Leo XIII, Pius XI, and Pius XII (Mystici corporis, art. 13; Humani generis, art. 27) and that of Vatican II and UUS. Again, “Doctrinal Note on Some Aspects of Evangelization” (SAE) stresses the permanent missionary mandate of the Church against all forms of indifferentism. Ultimately, Pope Benedict XVI moved the Church towards an integration of the vision of Pius XI and that of John Paul II. His successor, Pope Francis, continues to call us to love of the ones with whom we are in dialogue:

Dear brothers and sisters, let us ask the Lord Jesus, who has made us living members of his body, to keep us deeply united to him, to help us overcome our conflicts, our divisions, and our self-seeking; and let us remember that unity is always better than conflict! And so may he help us to be united to one another by one force, by the power of love which the Holy Spirit pours into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Amen. (Homily at the Closing of Week of Christian Unity, 2014.)

Towards an Integration of Faith, Hope, and Charity

John Paul’s vision of ecumenism was lofty. It will remain an inspiration for the years to come. It has already inspired countless concrete efforts, some more successful than others. The continued success of the implementation of his vision depends, in my opinion, upon its integration with the theological virtues of faith and hope, with teaching—which is foundational for all ecumenism—of Popes Leo XIII and Pius XI. Given that John Paul gave such a startling witness to hope, as well as to charity, I would stress here, chiefly, the integration of his vision with the virtue of faith.

Many well-intentioned ecumenists have lost sight of the uncompromising character of Catholic faith. Against this temptation, one must hold fast: There can be no bending whatsoever in the truths of the faith. Thus, we must recover the ever-valid teaching on the fundamental importance of truth, so marvelously defended by Popes Leo XIII and Pius XI. There is no ecumenism, worthy of the name, that would bend on the issue of the truths of our Catholic faith. Nor, conversely, can one afford to let the unconditional character of dogma dampen one’s hope. Vatican II charges Catholics with a permanent mandate: To hope for the full realization of Christ’s prayer. To this hope corresponds a grave obligation to labor seriously towards this end. This obligation is fulfilled in charity, by which we pilgrims “attune” our ears and our minds to our dialogue partner, without losing our bearings, that is, our very souls and the soul of Mother Church. Finally, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis draw Catholics into these deep waters of charity, without which—as Catholic faith solemnly teaches—no one can be saved.

The foundation annunciated by Leo XIII and Pius XI has an intrinsic harmony with the vision of Vatican II and John Paul II. It is only in the practice of implementing the vision of Vatican II, and John Paul II, that conflicts have arisen, often as a result of efforts that were well-intentioned. The intrinsic harmony becomes manifest in light of the ultimate purpose of the visible structures of the Church. As the Reformers (esp., Luther and Calvin) clearly recognized, and as the Magisterium today rightly emphasizes, the visible structures and rites of the earthly Church are at the service of the communion of persons. It was on account of this insight, one might hope, that the Reformers defined the Church as the “communion of saints.” In so doing, the Reformers downplayed the Church’s juridical and visible character. Catholic theologians and teachings (especially Vatican I) could not but respond by pointing to the ineradicable, albeit ministerial, importance of the hierarchy and the sacraments. Yet, both hierarchy and sacraments are ministerial; they serve the entire People of God on earth, and shall have no place in the afterlife, wherein God shall be all in all.

Since Vatican II, the Catholic ecclesiological focus has stressed not the juridical and visible elements, but the vitality of spiritual life that is the fruition of full membership, and the aim of earthly life. This shift in focus is in harmony with the deepest ecclesiological insights of the Reformers, even though the Catholic should not think that Vatican II, or recent Popes, have rejected or diminished Catholic dogmas concerning the visible and juridical character of the Church. Such teachings are still maintained, though often implicatione amante. Indeed, no one can come to the Father except through the Son, and the Son came in the flesh, and left us an institutional Church with sacramental acts whereby we are saved.

The communion of persons, so central to recent magisterial teachings, has its ultimate realization in a common participation in the Divine Life. This participation is established in men by the bond uniting them to the Triune God, and to one another (Ezek 36:26). This bond is the in-dwelling Holy Spirit, together with the infused gift of charity (Rom 5:5; 1 Cor 13), which in turn depends upon (the naturally prior gifts of) faith and hope. Through faith, hope, and charity, human beings are united cognitively and affectively with the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit. Supernatural communion with God, and it alone, grounds the lasting and satisfying communion of human persons with one another. Hence, through infused grace and the theological virtues, especially through charity, one is born a son of God (1 Jn 4:7) and a living member of the body of Christ (Jn 15 and 1 Cor 12–13). Charity, then, together with the resting of the Spirit upon the sanctified person, supremely constitutes communion, which is the very purpose of the Church (LG, art. 1). For this reason, the Catholic Church has ever insisted that charity—gratuitously infused in the very act of justification itself, whereby all that can be called damnable is totally expelled from the heart (Ps 51:10)—is absolutely necessary for eternal salvation. The reason for this teaching, ultimately, is another teaching, namely, that salvation is not merely redemption from punishment but, much more importantly, a living relationship with the Triune God, and with all other saints. In fact, eternal punishment (damnation) can be defined by the culpable loss of this caritative relationship with God and its aim—the beatific union.

Paradoxically, contradicting all protestations of “progressive” and “arch-traditionalist” Catholics—who share a “hermeneutic of discontinuity” about Vatican II—what John Paul II and Benedict highlight in terms of our attitude and approach (charity) is actually a crucial element of Catholic doctrine, which Pius XI rightly wished to guard. The way forward in the realization of Jesus’ prayer is the love of his heart (Jn 15), so that the desire underlying our ecumenical hope will be immeasurably elevated and purified.

Yet, if we are to attain genuine unity, we must be grounded in the fullness of truth that is entrusted to the Catholic Church, not as a product of human hands, but as a gift, a divine endowment. Without the truth, unity cannot set us free (Jn 8:32) in the freedom of the children of God (Gal 5:1; Rom 8:14–17). Hence, Pope Benedict, through the office of the CDF, stresses the link between the Catholic effort to include all men in the Catholic Church, properly respecting the dignity of every person, and the very love that should open the Catholic evangelist to the latent iconic wealth (wealth in potency) of the one whom he encounters, in Jesus name: “The primary motive of evangelization is the love of Christ for the eternal salvation of all. The sole desire of authentic evangelizers is to bestow freely what they themselves have freely received.” 8 Again, “The Christian spirit has always been animated by a passion to lead all humanity to Christ in the Church. The incorporation of new members into the Church is not the expansion of a power-group, but rather entrance into the network of friendship with Christ which connects heaven and earth, different continents, and ages.” 9

Clearly, Pope Benedict was presenting numerous indicators, specific and general, of a “hermeneutic of continuity.” Taking up these indicators, and articulating the harmony of Vatican II with the Catholic heritage, is one present and pressing task for Catholic theologians. In this way, pseudo-Catholic theologies will be thwarted from achieving their deleterious aims, and stubborn Catholic “arch-traditionalists” will come to see that the one faith has never abandoned the Church, nor she it!

So, therefore, may faith, hope, and charity abide (1 Cor 13:13)! May we, clinging to Jesus in love, be transformed into his image, more and more (Rom 8:29), being “stitched together” with him in his death, so as to rise with him in glory (Rom 6:4–5). May his hearers—following him from the Garden to the Cross—one day “all be one” (Jn 17:21), all living members of his body (Jn 15:5–7). We cannot fail—if we thus cooperate with his grace—to be united as one, here on earth, for the Spirit shall draw us together. May God unite what man has sundered!

- Lumen Gentium, art. 14, speaks of Catholics in whom the Spirit dwells as “fully incorporated” (plene incorporantur), of catechumens and of non-Catholic Christians as “joined” (coniunguntur) by explicit desire and baptism respectively, and of others as “related” or “ordered” to the Church (ordinantur). ↩

- Obviously, I am interpreting “subsistit in” (Lumen gentium, art. 8) as not altering the constant teaching of the Church, according to which there is a “full identity” between the Church founded by Jesus and the Catholic Church. Whereas some may dispute my reading, I would appeal to the recent clarification of the CDF on this matter: Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church” (hereafter, RSQ; English translation published in Origins 37 {2007}: pp. 134–36). I would also argue, with Fr. Karl Josef Becker, S.J. (Karl Josef Becker, “An Examination of Subsistit in: A Profound Theological Perspective,” Origins 35, no. 31 {Jan. 19, 2006}, and Fr. James T. O’Connor (James O’Connor, “The Church of Christ and the Catholic Church,” chap. in The Battle for the Catholic Mind, ed. William May and Kenneth Whitehead, pp. 248–263 {South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2001}), that efforts to interpret this term as an alteration of past doctrine come to grief with the analogy of faith. This article is not the place for a full consideration of the issue. I would only sketch the following argument in brief. Before the recent clarification, the only reasonable Catholic reading of “subsistit” that upholds some alteration of past doctrine was the following: The Church of Christ is non-exclusively identical with the Catholic Church, e.g., Ralph Del Colle (Ralph Del Colle, “Toward the Fullness of Christ: A Catholic Vision of Ecumenism,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 3 {2001}: 201–211). Positions maintaining something less than non-exclusive identity were, even before the clarification, simply indefensible. See, for instance, that of Richard McBrien (Richard McBrien, Catholicism {Winston Press, 1981}, p. 685). Still, even this non-exclusive identity appears problematic on several counts. First, Vatican II states time and again that Peter and his successors are to guide the entire people of God, the whole flock, the universal Church, the whole Church, the whole assembly of charity, etc. But Peter’s successor is the head of only one Church, the Catholic Church. Therefore, the Church of which he is head, that is, the whole Church, is simply the Catholic Church. Second, the Catholic Church is the Mother of all Churches, not a set of federated particular churches tantamount to one large sister church of which non-Catholic churches are in turn sisters. Third, Vatican II emphatically teaches that the Catholic Church—not simply the Church of Christ conceived as somehow non-exclusively identical with the Catholic Church—is necessary for salvation, with all the due qualifications that everyone understands (circumstances, hidden cooperation with grace, etc.). Each of these three considerations warrants a strict reading (est); together, they appear insurmountable. The Magisterium has recently stressed that the phrase employed in Vatican II, subsistit in, preserves the “full identity (plenam identitatem)” of the Church of Christ and the Catholic Church (see RSQ, Response to the 3rd Question). For a more adequate treatment, see my “‘Subsistit in’: Non-exclusive Identity or Full Identity?” The Thomist 72 (2008): 1–44. ↩

- All translations of Vatican II are from Flannery, ed., (Northport, NY: Costello Publishing Company, 1998). ↩

- Faithful to Pius XI’s teaching, therefore, Catholic ecumenism is all about a “return” to the Catholic Church. However, one must reject an “ecumenism of the return” (as, e.g., Pope Benedict XVI, comments in Cologne, 2005) in the sense of an ecumenism that suffers from any of the following problems: a) Catholic lack of appreciation for the genuine liturgical and theological gifts unique to non-Catholic communions; b) Catholic lack of charity towards non-Catholic communions; c) Catholic lack of appreciation for the legitimate differences of rite, etc., among particular Catholic Churches; d) failure to differentiate those who deliberately left full communion from those who find themselves in a disunited state; and e) a monolithic ecumenical hope, not tolerant of legitimate differences, rooted in the misconceptions just presented. What is unfortunate is the present failure of theologians to identify the harmony between Pius XI and current Catholic ecumenism. This vacuum leads to a false dichotomy: return to some particular era of Catholicism vs. hope for some unidentifiable future Church that will accommodate non-Catholic Churches qua non-Catholic. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Address of His Holiness to the Roman Curia (December 22, 2005). ↩

- See note 2. ↩

- Translation from: www.vatican.va. ↩

- SAE, art. 8; translation: www.vatican.va. ↩

- SAE, art. 9. ↩

Dr. Malloy this paper on ecumenism is right on target with the Traditional teachings and Canon law of the Catholic Church . I pray to the Holy Spirit that single persons and whole congregations come to believe and live the Truth about God with the Roman Catholic Church. This has happened already with Anglican priests changing to our priesthood granted by a provisional canon from Pope Paul VI, and many individual Anglican congregations have accepted the Tradition as well as other non catholic congregations. We have them in Dallas.

As a Traditional Catholic who supports the SSPX, there are a few areas where your thesis will create discomfort.

More importantly will be the contradiction between Cardinal Kasper and the opinion that there is consistency between the pre and post conciliar notion of ecumenism.

Cardinal Kasper stated that the Ecumenism of Return has been set aside for Ecumenism of a Common Journey. When the Traditional Anglican’s, faced with severe moral and theological issues within their religion and its leadership, wanted to enter the Church – Cardinal Kasper objected to the event.

The actions of the post conciliar pontiffs, most notably Paul VI, John Paul II, and Francis, reinforce the conclusion that Ecumenism is not about a return of ‘dissidents’ to the Church but of something else.

Even the argument made concerning ‘subsistit in’ will cause dissonance, even when incorporating “Responses” because if ‘subsistit in’ means ‘est’ … then why not just say “est”.

The phrasing of “Responses” obscures the reality that there is but one Church by the following statement:

Question 2: It is possible, according to Catholic doctrine, to affirm correctly that the Church of Christ is present and operative in the churches and ecclesial Communities not yet fully in communion with the Catholic Church, on account of the elements of sanctification and truth that are present in them.[9]

This appears to contradict the earlier points made in responses. How can the One Church of Christ, which has the four marks etc, can be present and operative beyond its boundaries. If those in invincible ignorance are not actual members of the Church (Pius XII), then how is the Church of Christ present beyond its Actual Membership?

In short, the boundaries of the Church are obscured and ‘Responses’ does little if anything to make them clearer.

The fact that footnote #9 refers to Ut Unum Sint with refers back to Lumen Gentium simply creates a circular reference. This supports the Traditionalist perspective that references to pre-conciliar magisterium in support of the present Ecumenical endeavor are sparse because there are none.

My apologies for the rambling nature of this post. I am looking forward to your thoughts.

Cordially,

Andrew

Andrew,

I have dealt at length with your important concerns in my article in The Thomist. It is too involved to summarize here. Perhaps in a future article for HPR? But in brief. Kasper’s remarks are problematic given their ostensible intent. However, there is a grain of truth in what one can use by the phrase “not an ecumenism of return”. The grain of truth is this: These people were raised outside the True Church. Thus, they are not “returning” as though authors of disobedience. It were different for Henry VIII and Martin Luther and Calvin and others who have more proximately committed heresy or schism or disobedience (Feeney) etc. However, what is misleading in Kasper’s remark is his apparent implication that we do not seek every last person to become Catholic. That is false. That goes against the Tradition. It goes against Lumen Gentium, art. 16. For we labor that every last man woman and child enter the fold founded by Jesus Christ.

Who ever believed that the Church had a presence outside of its full instantiation? Well, let us ask. Did anyone ever think that most of the faith was present anywhere outside the Church? That any valid sacraments were present anywhere outside the Church? That charity could exist outside the Church? I submit that Pius XII and Sebastian Tromp, the man behind the encyclical Mystici Corporis, both believed these things. I suspect they are part of a long tradition.

The difficulty you pose is important. I ask you to distinguish what I am saying from what Kasper and Sullivan have been saying. They propose something like this: The non-Catholic churches and communions enjoy the presence of the Church of Christ but not of the Catholic Church. (Or, the presences in each case are distinct.) That idea is totally false. Rather, the truth is: the Catholic Church is the Church of Christ. And this Church has an essence, a mysterious essence, that nonetheless can be to some extent defined / described. I believe that “societal order” is integral to that definition. Therefore, only the Catholic Church has this essence. However, there is in this societal order a complex set of materially describable elements, etc. (Eucharist, Bishop, Bible, Tradition, etc. etc. etc.). Now, some of these materially describable things exist also outside the Catholic Church, i.e., outside the Church of Christ (idem!). Yet, these elements come from the Church of Christ and therefore impel back to the Church of Christ. They belong by right to the Church of Christ. The Holy Spirit inwardly moves their bearers back to the Church of Christ. Since the Church of Christ just is the Catholic Church, we can restate those sentences accordingly. Now, to have partially what belongs to another in full measure is to “participate” it. Hence, these non-Catholic entities “participate” in the Church of Christ, i.e., in the Catholic Church (idem!).

That’s it.

What is the goal of Ecumenism? The only ultimately legitimate goal, the necessary goal for any Catholic, is the full union of these non-Catholic churches and communions with the Catholic Church. When they achieve this unity, they shall be sister churches with other sister churches in the Catholic communion. E.g., the Orthodox churches will be sister to the Dallas Diocese, etc. Will they be “sister” to the Catholic Church? (Sullivan’s implication.) NO! That would be totally false. For the one true Church is the Catholic Church.

I grant that some practical actions of recent high ranking prelates are very trying on the soul, can tend to cause scandal, etc. Creeping infallibility may be the bull-horn by which such actions mislead people. Let us pray for ourselves, miserable sinners that we are, and for those who shepherd us.

Dear Dr. Malloy,

Thank you for your kind and thorough response. I would like to delve deeper in to a couple of elements.

I will collect my thoughts and reply here. If you would like to continue the discussion offline, please let me know.

Cordially,

Andrew Procca

Questo è, per la maggior parte un buon articolo, ma l’idea che una “chiesa” esiste al di fuori della Chiesa cattolica è estranea alla sua teologia. Davvero, è stato condannato da Pio X, vale a dire come la “teoria dei rami”.

In English: This is, for the most part a good article, but the idea that a “church” exists outside of the Catholic Church is no stranger to his theology. Davvero was condemned by Pius X, that is to say as the “theory of branches.”

Dearr Dr. Malloy,

My apologies for the delayed response.

“…The grain of truth is this: These people were raised outside the True Church….”

I see the problem cast in a slightly different light.

They protestants are baptized non-Catholics. From the moment they were baptized to the moment when they rejected the Catholic Church (in an objective sense) they were members of the Catholic Church. When they rejected the Church that objectively separated them from the membership of the Church. Subjectively, they may not be culpable (see Pius IX, XII), but objectively they have ceased to be members of the Church.

In that sense, that I would submit that ecumenism of return is the correct perspective.

With respect to:

” … However, there is in this societal order a complex set of materially describable elements, etc. (Eucharist, Bishop, Bible, Tradition, etc. etc. etc.). Now, some of these materially describable things exist also outside the Catholic Church, i.e., outside the Church of Christ (idem!)….”

These elements may exist outside the Church (Apostolic Succession etc), however, following the doctrine of the Four Marks, only where all Four are present is the Church of Christ (Mystical Body of Christ) present. I would like to emphasize that the mark of Unity (Unity of Faith, Government, Worship) is always absent from the Orthodox and Protestant religions. Only when they as individuals or organizationally return to the Church are all Four Marks unified.

That is not to say, to make a clear distinction, that the individual members of the Orthodox and Protestant churches cannot be united to the Church of Christ ‘in voto’. They may have, as Pius XII described it, a relationship with the Catholic Church due to their invincible ignorance etc. However, that relationship is tenuous and easily broken. If they have achieved a state of grace, then they are linked to what has been called the ‘soul of the Church’. However, objectively, we have no way of knowing when or where this is the case.

Further, in the case of the Orthodox, as they have apostolic succession and valid sacraments, then provided the individual is in a state of invincible ignorance and a state of grace – then they present no obstacle to the Grace of the Sacrament.

However, if this is not the case then the Grace does not flow and we know that:

“… Whosoever, therefore, knowing that the Catholic Church was made necessary by Christ, would refuse to enter or to remain in it, could not be saved….” LG14

Concerning “… mysterious essence … ” if this is the equivalent of the ‘soul of the Church’ then, we may be strictly speaking about semantic terms and not a difference in principles.

Cordially,

Andrew