Our unwillingness to live our lives upon the horizon of the infinite is an unwillingness to accept the authority of God, who speaks, through his Church, to our consciences. This is the heart of the tension between the secular power and the authority of the Church—and it is the problem we face today.

During the presidential election cycle in 2008, I sat on a panel at the small Catholic college where I teach theology to discuss the salient issues of the election with interested voters, offering them a Catholic perspective. At the time, I saw the fundamental issue as an option for a culture of life or a culture of death. At issue in today’s political stand-offs, I believed, is the question of whether—when all is said and done—death will overtake life, and place limits on our moral principles. Or, will life conquer death, such that we can live by the dictates of our Catholic consciences, no matter what the exigencies of this world might recommend. In the United States, our form of governance gives us choices—choices that we make in the election booth. So I attempted to frame the central issue in the election as the choice between these two cultures: the culture of life and the culture of death.

Some in attendance did not understand the implications of this option. They had read Douglas Kmiec’s book, 1 and argued that Catholics could vote for a particular candidate in good conscience because of his support for other “Catholic social teachings,” even if he works to promote certain per se evils (like abortion) and embraces a worldview opposed to the truth of the Gospel. They were wrong. Whatever John McCain’s failings may have been, no Catholic, in my view, had any moral business supporting Barak Obama, or consenting to cast a vote for him in that election, because it was clear that he espoused a culture of death, and that he would work to implement its agenda. I foresaw, for that reason, that he would find a way to pit the state against the Church, because, in the past, those who have espoused his basic views have always done so. Let me explain.

Even before John Paul II’s pivotal encyclical letter, Evangelium vitae (1995), the Catholic Church had been drawing an essential contrast between the “culture of death” and the “culture of life.” In fact, the concept goes all the way back to the Bible—to the choice between the deadly “Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil” and the “Tree of Life” through Covenant with God. The perspective of the culture of death is the perspective from which, whether implicitly or explicitly, a person denies God’s authority over life, and holds that this world—the world of time and space and matter—is the only one that really counts. Religion and morality can be tolerated only insofar as they move within the boundaries of the present world, and not beyond it—only so long as they do not challenge the authority of the province of all that’s born and dies. When people who hold this view of the universe enter the political sphere, they naturally seek to advance it, and so, they invariably promote the claims of secular power over the authority of God in the interest of the “real” world of the “here and now.”

By contrast, the Catholic Church, cannot acknowledge the boundaries of time, space, and matter and, thus, stands for a limitation on the authority structures of this present world. Those authorities rely upon the power of death, which itself has been overcome by life. This tension is inescapable. The very existence of the Catholic Church represents a challenge to the coercive power of the state.

The God of the Catholic Church, in other words, is not like any pagan god, limited to a geographical boundary and the countervailing claims of other gods in the pantheon. The Catholic God is a “catholic” God—a truly universal God, whose moral edicts constitute an absolute boundary beyond which the political community—limited by its very nature within time, space, and culture—simply may not move.

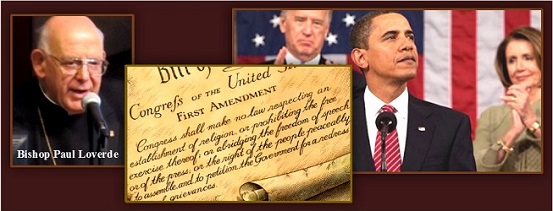

Pope Leo XIII had said, in the late 19th century, that “capricious” laws have no claim on conscience.2 And long before that, St. Thomas Aquinas had insisted that “an unjust law is no law at all,” and that it “must in nowise be obeyed.” 3 Civil disobedience is a decidedly Catholic concept, and is now being invoked by our bishops in response to the capricious and unjust laws taking effect in our own country—in particular, the mandate from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to pay for the coverage of a slate of immoral medical interventions that the Church has opposed in her official teaching from time immemorial. Bishops Paul Loverde of Arlington and Francis DiLorenzo of Richmond threw down the gauntlet on this matter, when they proclaimed unflinchingly that: “We cannot—we will not—comply with this unjust law!” 4 In the background, we can hear the words of Ignatius of Antioch, who died at the hands of the Roman Empire as an eager witness to the authority of God and his Church, echoing from the early second century: “I spoke out in a great voice,” he exclaims, “God’s voice!” 5

Indeed, the issue before us has played itself out in history. In the Middle Ages, there were numerous challenges to the authority of the Church by the secular powers, resulting, time and again, in the reassertion of the Church’s teaching on so-called “divine right.” According to this doctrine, secular authority is limited by the authority of the natural moral law, over which the Church herself is the final judge in the present world. This teaching means that, within the sphere of morality, secular power must defer to the authority of the Church. In its fundamental elements, this teaching is still in force today.

For centuries, of course, the Church has been involved in secular affairs to a greater or lesser extent in different cultural contexts throughout the world and, sometimes, this involvement was favorable to the Church and her interests. Sometimes it wasn’t. But I’m not interested here in providing a complete picture, so long as my reader understands the real point I’m trying to make. It’s a very limited one, but I think an essential one. In the great sweep of history in our fallen world, there is always a tendency—to which we have traditionally given the name “concupiscence”—for human beings to desire power, pleasure, and wealth beyond their due proportions. 6 Thus, those who hold secular authority are always tempted to consolidate power, rather than share it. For this reason, they tend to resist the authority of the Church as she persuades the human conscience on matters of morality and, thereby, places a limit on the practical exercise of secular power. There is no conspiracy theory here—no secret society plotting behind the scenes and lurking in the shadows. Rather, at every moment throughout the sweep of history, every human being must make a choice whether to live only for this world and for himself on the horizon of the limited, or to live for God and “cross the threshold of hope” upon the horizon of the infinite. Our unwillingness to live our lives upon the horizon of the infinite is an unwillingness to accept the authority of God, who speaks, through his Church, to our consciences. This is the heart of the tension between the secular power and the authority of the Church—and it is the problem we face today.

So looking back historically, then, we can see this struggle illustrated in numerous instances, related to one another only on the level of the inner choice for the finite against the infinite: to “worship the creature rather than the creator.” 7 An awareness of these events makes it clear to us that what we are facing in our own time is not a passing fad, and needs to face our opposition. In one pivotal episode of this constant struggle, for example, Henry I of England went toe-to-toe with St. Anselm of Canterbury over an issue known to scholars as “lay investiture.” St. Anselm refused to allow Henry to bestow the symbols of their office on newly-consecrated bishops, because in doing so would implicitly assert that the authority of the Church is derived from the state, rather than from God. Anselm was correct in seeing this assertion as heretical, and as seeing the practice of lay investiture as an offense against the Church. If the authority of the bishop comes from the state, and not from God and his Church, then the Church is the property of the state and not of God, and there is no limit to secular power. So, when Henry refused to resign his claim in this case, Anselm, backed by Pope Paschal II, threatened the king with excommunication, and Henry, only then, decided to try to work things out, because he knew that excommunication would mean the overthrow of his monarchy. Political authority can only be exercised in accord with the will of God, and official condemnation by the Church would deny him his title to govern. In today’s conflict, the catalyzing issue is different (the HHS Mandate), but the root problem is exactly the same.

This struggle, though, is always with us. A few hundred years after the controversy between Anselm and Henry I, and with an entirely different catalyzing issue, Henry VIII went up against the Church, and prevailed where Henry I had failed. When the Church refused the latter Henry a decree of annulment, which would have allowed him to dismiss his lawful wife, Catharine of Aragon, and marry Anne Boleyn, he declared himself the head of the English church, and annulled his own marriage. He knew that the only way to do what he wanted, politically and without restriction, was to place the Church under the authority of the state, and that’s exactly what he did.

Henry’s totalitarian designs would come, of course, at a terrible cost—a cost Henry was willing to pay. England was the most devoutly Catholic country on earth at the time, so the seizure of the authority of the Church could only be achieved through the shedding of blood. Henry’s minions executed hundreds of Catholics in every state of life, evicted monks and nuns from their abbeys, and looted ecclesiastical properties of their sacred objects. It was during this time that St. Thomas More, who had been Henry VIII’s chancellor, was sentenced to death for his refusal to renounce his submission in conscience to the teaching authority of the bishop of Rome. Elizabeth I later secured the total power of the state from the threat of a resurgent Catholic populace by instituting penal codes. She barred Catholics from public service, and dispossessed lay Catholics of their means of livelihood, condemning them to inescapable poverty, while enacting further edicts making it illegal for them to beg for relief.

But the struggle before us is not just a problem for the Middle Ages. It would be foolish, in fact, for us to pretend that this sort of horror could not happen again, or could not happen in a country like our own. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the secular government movements erupting throughout the world resulted, time and time again, in the persecution of the Church. It happened in Mexico, in Portugal, in Spain, and in Russia. From Russia, it progressed throughout the whole Soviet Bloc. It happened in China, in South Korea, in Myanmar, and in Cuba. Each of these events has its own history and its own catalyzing influences, but the root problem is exactly the same: where the secular authority seeks to have the final say, the Church has got to go.

Perhaps, the most notable case, however, comes during the period of socialist fascism in Germany and Italy in the time of Hitler and Mussolini. That event resulted in the Church mounting a concerted resistance against the secular powers, complete with covert operations, overt pronouncements, lay enlistment, and martyrdom on a scale that takes us back to the time of Diocletian. The particular circumstances in this event are surely complicated, and its catalyzing influences distinct, but again, the central issue is the same. At least, that’s what Pius XI thought.

Pius had directed several encyclicals against the secular regimes of his time as they arose against the Church in the course of his papacy. In these encyclicals, he gradually developed the Church’s teaching on the relationship between Church and state, and the role of conscience on the part of the laity. A study of these encyclicals makes clear that the Church does, indeed, take sides in political contests when a political party assumes totalitarian aspirations, positioning itself as an enemy of the authority of God. Pius XI wrote indefatigably against these regimes, and officially condemned the Nazis of Germany and Mussolini’s fascists.

Fascism may have been defeated, of course, but there are still secular government movements of different forms around the world. The Church still opposes communism, even today, and stands as a challenge against the totalitarian claims of Marxist states. The conflict here is so real that the true Church has moved underground in these places, and the Pope must create cardinals “in pectore” (i.e., secretly, “in the bosom” of the Holy Father), because so close a public relationship with the bishop of Rome would surely lead to still further persecution in the cardinal’s own country.

This is the sad and frightening truth about the world. It goes back all the way to the early Church, and even to the time of Herod, who so feared the implications of a religious authority, that, at the suggestion of the birth of the Messiah, he ordered the slaughter of every male child under the age of two in the region of Bethlehem. In the apostolic age, the struggle continued as Christians refused to genuflect to the emperor as if his authority faced no limits, but, instead, reserved the right knee for Christ alone. The secular authority of the Roman Empire thus positioning itself as a culture of death, comes to be featured as such in the Book of Revelation, where it is cast as “Babylon”—the ancient pagan enemy of the people Israel—and Nero is assigned the number of the beast, a number that depicts the hopeless frustration of a world without its Sabbath rest, and constrained to its own limits by the dark horizon of death. By contrast, the acclamation, “Jesus Christ is Lord,” 8 strips Caesar of his title, and Christ, beaten and bound, tells Pontius Pilate that even the earthly power of Rome is totally subject to the authority of God. Jesus, triumphant over death itself, “rules the nations with an iron rod” 9—with an authority, in other words, that can never be overridden. The fundamental option between these two worlds—what St. Augustine had called, “the City of Man” and “the City of God,” and what John Paul II had called “the culture of death” and “the culture of life,” is a basic feature of the whole narrative of the drama of salvation. We can see it crystallized for us in the scene in the Gospel of John, where Pilate asks the people, “Shall I crucify your king?” 10 Their reply is precisely to the point: “We have no king but Caesar!” 11

So, in the time of the Nazis, when Jews and Catholics were slaughtered by the millions in death camps and on the streets, the real enemy of the new Reich was God himself, who spoke to the consciences of human beings through the Yahwhistic Covenant and, thereby, placed a limit on what the state could presume to do. God had to go. But God is the God of his people: of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob. To get rid of him, his people had to be contained.

This is where we find ourselves again, today, in the United States, under the regime of Barak Obama, who, espousing a Marxist philosophy, adopts a socialist politic, and sees the state as the supreme authority in human affairs. One need only read his two autobiographies 12 to understand this fact. Obama may identify himself as a Christian, but he holds to a purely secular movement in history, and so, to a purely secular solution to the problem of human suffering. The assertion of a supernatural destiny is an affront to such a worldview, and is thus seen by those who espouse that worldview as an instrument of oppression. Consequently, people like Obama criticize religiously informed conscientious objectors on their policies which are seen as being “on the wrong side of history.” For them, the proposition of a supernatural destiny—an eschaton beyond history, and to which history itself must be responsible—can only serve to lull humanity into complacency with its assurance that the problems of this world will find their resolution in the next. The “progress” they seek is thwarted by the belief that this world is accountable to an authority higher than itself. Thus, by looking only within the horizon of this life, this Marxist thesis is, by definition, a philosophy of the culture of death. It rests upon the belief that, in the end, this world is the only world there is, and that it is only within the horizon of life staked out by death that our moral values have any meaning at all. This position gives the limitation of life —the fact of death—as the final say in all matters of conscience and morality. From this point of view, there can be no supernatural authority to bind the human conscience, and appeals to such authority cannot be tolerated by the state.

This is why President Obama so disdainfully dismisses those who “cling to their religion.” 13 It’s also the reason that under his administration, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission actually had the temerity to tell the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America who could exercise a ministry in their name. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, in what’s popularly known as “the Tabor case,” 14 in which the Justices held firm for religious freedom in a rare unanimous decision against the administration, inclusive of Obama’s own appointees. But Obama, who had once criticized the very left-leaning Warren Court for not throwing off the constraints of the Constitution, 15 continues to fight against the First Amendment, because in our constitutional framework, it’s the key to limiting secular power. The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution exists to correct the tyrannical consequences of the English Reformation. By forbidding the federal government from “establishing a religion” or “prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” and by safeguarding “the freedom of speech, and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances,” the framers restored the voice of God to the public square. Once again, divine authority had been placed beneath secular authority in the English Reformation, rendering the secular power absolute. Without resolving the religious disputes about who speaks with the authority of God, the framers acknowledged the fact that the secular power could not be permitted to operate without a check on its authority from the outside. Wherever the voice of God was to be heard, they thought—and they all had their personal opinions about that—it had to be given a place at the table of public discourse, and the secular power could not be placed above it. The “catholic” God could once again speak to his people, uncensored by the secular power, and his Catholic Church was free to preach his Gospel of Life.

People in American politics who hold totalitarian aspirations don’t like this amendment because, by protecting the Church from the state, it checks the State’s hold on power. The present issue surrounding the HHS Mandate is only the latest assault, but, like the Tabor Case, it cuts to the very core of the amendment’s purpose, and highlights the perennial struggle between secular power and the authority of God. The Obama administration wants the Catholic Church to acquiesce to their demands that her institutions, so fundamental to this nation’s infrastructure, check the Gospel of Life at the door, and pay for contraception, sterilization, and abortion, in contravention of the will of God.

We should take this challenge very seriously, because tyranny is always a living threat, and not even a constitutional republic is immune to it. When Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany, he did so under similar economic circumstances to those of the United States in the 2008 and 2012 elections, in a country with a constitution much like our own. He summarily went to war against the Church, and sought to build an empire free of conscience. All attempts at negotiation only led to grief for the Church as the state sought total power, unchecked by the commandments of God. Then, on two separate occasions, Pius XI responded by ordering encyclicals, written in the language of the people, to be read from the pulpits at the risk of death for priests, bishops, and laity alike—one calling the faithful to resist the rule of the Nazis in Germany, and the other calling the faithful to resist the fascists in Italy.

In our own time, Obama has declared war on the Catholic Church, and seeks to establish a political empire unconstrained by conscience. Until now, the Church in the United States has negotiated with the secular powers, agreeing to curb her speech on political matters in exchange for a tax exemption that very soon may not even matter anymore. This attempt at negotiation, too, has only led to grief for the Church as the state has sought total power unchecked by the commandments of God. Obama’s so-called “accommodation” introduced with great fanfare on February 10, 2012, was just another insult in which he reminded us that he is only requiring immoral treatments to be covered by the insurance companies whose policies we are forced to buy, not by our institutions directly. It changed nothing. In fact, Nancy Pelosi even went so far as to say that, in her view, even self-insured religious employers, like the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., should be made to comply with the mandate in the absence of a third-party provider. In the wake of the Hobby Lobby ruling, it seems likely that Pelosi and the President will be rebuffed, but if Barak Obama and his political allies get their way, our institutions will either submit to the unchecked authority of the secular power in renunciation of the “catholic” God, or the state will wield the sword against them. And this is to say nothing of the burden placed upon individual Catholic employers in secular work who are forced to violate their own consciences under state mandate. The Hobby Lobby decision did not completely resolve that question. Today’s administration manifests totalitarian aspirations, in the face of which increasing numbers of Catholic bishops are speaking out, and are exhorting the faithful from the pulpits in their churches to stand firm in conscience against the coercive power of the state, as it attempts to claim for Caesar that which belongs to God alone.

Of course, any faithful Catholic knows that, whatever persecutions may await—and I’m convinced that they’re coming—there’s a bright side to this assault. The Catholic Church has been consolidated around this issue in a way that all our internal efforts to establish unity have not been able to realize. And, we suddenly find that the catalyzing issue in today’s debates has been recast by the secular power’s overplaying of its hand. What they thought would be a winning issue for them, in a society that uses artificial contraception ubiquitously, has blown up into a major public relations crisis for the Democrats in Washington, with the result that, in their growing distrust of worldly power, the people are turning to the Catholic Church with a suspicion that she might just have wisdom on her side. It is an example of the “sign of Jonah” wherein God turns the demonic power against itself to defeat Satan at his own game, because Life is stronger than Death, and Love is stronger than Sin.

We know that much. When Pope Pius VII was imprisoned by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809, in yet another episode of this age-old saga, the latter purportedly declared to Pius his intention to destroy the Church. Pius laughed in his face and explained that, if the Church could survive for nearly two millennia the fallen-ness of all its members eating away at the Body of Christ from within, Napoleon had surely set himself an impossible task. People like Napoleon, though, will always try, and today, in the United States, the battle is on.

Knowing that God wins in the long run, however, is not an excuse to go back to sleep again. I fear it will be very bad for Catholics, in the years and decades to come, if we do not fight hard on the short-term front and win. We really are in a kind of “war” right now against the secular power of the state, and the stakes are high indeed. No matter what happens, of course, we should find courage in the fact that God can never really lose, and that even the end of the world is not the end of the world for us. But how things will end in our time is largely up to us—the individual members of the Church, mostly laity—whose greatest weapon against tyranny is a vote cast from an authentically Catholic conscience.

- Douglas W. Kmiec, Can a Catholic Support Him? Asking the Big Question about Barak Obama. (New York: The Overlook Press, 2008). ↩

- Pope Leo XIII, encyclical letter, Libertas Praestantissimum (20 June 1888), § 10. ↩

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I-II.96..iv. See also St. Augustine, De Libero Arbitrio I.5. ↩

- Most Reverend Paul S. Loverde and Most Reverend Francis X. DiLorenzo, “A Letter from the Bishops,” January 30, 2012 ↩

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Philadelphians 7.1, My translation. ↩

- Cf. CCC 2514–2520. ↩

- Cf. Romans 1:25. ↩

- Philippians 2:11. ↩

- Revelation 2:27. ↩

- John 19:15. ↩

- John 19:15. ↩

- Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (New York: Crown Publishers, 2004); Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (New York: Random House, 2006). ↩

- This image comes from a speech by Barack Obama at a San Francisco fundraiser during his 2008 presidential campaign. ↩

- Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, et. al. (United States Supreme Court Decision:11 January 2012). ↩

- Radio interview: Odyssey (Chicago: WBEZ, 2001). ↩

Very well said. You identified the basic task before us: to form the Catholic conscience in our homes, parishes, and schools.

Let’s get to work…

Sept. 30th…I am so very grateful for this article which calls things as they are, and describes what this Administration is doing to eliminate freedom of Religion. Let us never forget that at the Democratic National Convention, the Democrats had eliminated the Name of God from their platform. When they realized this could harm them politically, the one on stage called for a vote: should we put the Name of God back in – there was a resounding cry of ‘NO’! So he tried again for a vote and again – NO! so after listening to his earphone, he declared that God was back in…and there were loud boos at this news…they did not want God. They have become, in fact, the party of death. Dietrich von Hildebrand declared long ago: “A country that legalizes the killing of its own children is doomed.” Nancy Pelosi, a Catholic, wants abortion to be unrestricted and promotes the killing of preborn babies aggressively; she does not simply ‘accept’ this barbaric practice but she promotes it. The term ‘abortion’ has lost its impact – we should begin calling it what it is: “The Democratic agenda aggressively promotes the termination of human life in the womb.” What politician would stand up and say: “I support unconditionally the termination of human life in the womb.”?