The ranks of those declared blessed and saint by the Church under the guidance of the Holy Spirit constitute the great array of our brothers and sisters who have been lifted up as models of holiness and powerful intercessors. While blessedness and sainthood do not mean perfection in every area of life, those declared so by the Church are truly worthy of our admiration, and their commitment to Christ is to be imitated.

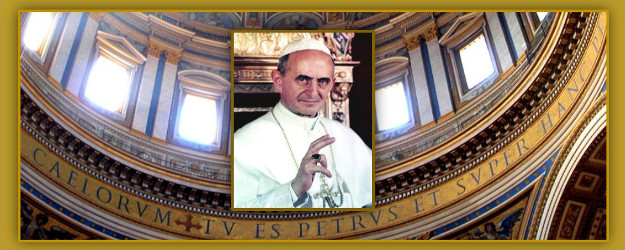

The beatification of Pope Paul VI on October 19, 2014, at the conclusion of the extraordinary synod on the family, indicates that the Holy Spirit has affirmed the holiness and exemplary virtue of Giovanni Montini through the occurrence of a miracle. While mortal and human, therefore prone to weakness, like the rest of us, Montini was a man utterly devoted to the Lord and the Church. While interpreted through more political lenses than most of us whose lives go relatively unnoticed, he held fast to the core of Catholicism. While attempts were made to hijack his papacy in support of everything from liturgical minimalism to Marxist Communism, he provided the essential link in Pope Benedict’s hermeneutic of continuity between the opening of the doors to fresh air by Pope Saint John XXIII and the fulfilment of the Vatican II vision in the legacy of Pope Saint John Paul II, and beyond. Having canonized these two popes, Pope Francis now paves the way for the same honor to be bestowed upon Paul VI, who, despite facing personal weakness and a maelstrom of ecclesiastical and societal conflicts, held the Barque of Peter steady through the tumultuous post-conciliar waters.

Authors in the years after the Council shed light on the life and times of Pope Paul VI, permitting today’s generation of Catholics to understand a significant era of the Catholic Church which they did not personally experience, and the factors that contributed to the Church as she is today. As early as October 1963, a mere four months after being elected as pope, his papacy was perceived as a riddle amidst various political machinations. Alice-Leone Moats reported in National Review that L’Unita, the magazine of the Italian Communist Party, “joyfully hailed the elevation to the throne of St. Peter ‘the workingman’s archbishop,’ ‘the man who typifies the progressive group of the Roman Catholic Church,’” only to lament “four days later” that “the election of Montini represents the contrary of that ‘revolutionary’ or, at least, ‘exceptional’ choice which alone could have satisfied the public.”1 Paul VI was no more the pope the “leftists” anticipated, than Jesus was the Messiah the Zealots expected. There was to be no “revolution.” Thanks be to God that neither the mission of the Church nor that of the papacy is to “satisfy the public.”

Disappointed that he was not what they hoped for, Moats continues, “the Communists” and “assorted left-wingers” “continue to hope that they were right when they thought that Montini was their man or, at any rate, that by means of flattery, threats, propaganda, misrepresentation, they can turn him into their man.”2 They did so by playing up what they thought positive in his papacy and downplaying the perceived negatives. After Paul VI issued an explanatory note confirming the supreme authority of the pope relative to the publication of Lumen Gentium,3 “the progressive majority of Council fathers went home after the third session, thoroughly discouraged and demoralized” at the realization that it was not going to progress as they imagined.4 On the other end of the political spectrum, traditional Catholics labeled Paul VI Protestant at heart and “reviled his memory”5 for authorizing changes to the Missal of Pius V.6 He is a hotly debated figure, a tragic symbol of the dizzying times in which he served the Church, a riddle not easily solved.

Adding to the confusion was the influential media, neither well informed nor supportive of the Church. In a speech to the clergy of Rome, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, himself a peritus at the Council and a prelate in leadership in the Church in the decades following it, explained what he observed in the time of Pope Paul VI.

(T)here was the Council of the Fathers—the true Council—but there was also the Council of the media. It was almost a Council, in and of itself, and the world perceived the Council through them, through the media.

So while the whole Council—as I said—moved within the faith, as fides quaerens intellectum, the Council of journalists did not, naturally, take place within the world of faith, but within the categories of the media of today, that is, outside of the faith, with different hermeneutics. It was a hermeneutic of politics. The media saw the Council as a political struggle, a struggle for power between different currents within the Church. It was obvious that the media would take the side of whatever faction best suited their world. There were those who sought a decentralization of the Church, power for the bishops, and then, through the Word for the “people of God,” the power of the people, the laity …

And we know that this Council of the media was accessible to all. So dominant, more efficient, this Council created many calamities, so many problems, so much misery, in reality: seminaries closed, convents closed, liturgy trivialized … and the true Council has struggled to materialize, to be realized: the virtual Council was stronger than the real Council. But the real strength of the Council was present, and slowly it has emerged and is becoming the real power which is also true reform, true renewal of the Church.7

One might argue that “misery” and “calamity” are strong and dismal language for describing the work of the Spirit through the Council and its unfolding within the Church. Still, this is precisely the point: while the Spirit was, indeed, at work inspiring the bishops to formulate a vision for transmitting the Church’s teaching within the contemporary context, the media was, in large part, responsible for obscuring the documents containing the teaching of the Council Fathers from the view of the laity, and presenting a skewed description of the Council to the world outside the official sessions. The oft-touted “spirit of Vatican II,” according to the “hermeneutic of discontinuity,”8 was an ethereal image of the mission of the Church that became malleable according to the whim of any agenda or interest group. From this scenario arose the miserable calamity that we, as a Church, have struggled through ever since the mid-1960s. We have not had the luxury of living out the 16 documents of Vatican II undisturbed from within the faith, but instead, have suffered under constant conflicts between ideologies. It was too late to put the lid on the confusion the media had precipitated, with the help of many inexact (if not heretical) statements by the Church’s own leaders and scholars, by the time the significance of the problem was realized. It was through the filter of the sensational headlines that the Second Vatican Council and the papacy of Blessed Paul VI were viewed by the public. People who never read the Council documents formed a variety of opinions about the Council’s intentions.

One such headline that changed the entire relationship between Catholics in the pew, the leadership of the Church, and the world at large, followed the preliminary reports of the papal commission, charged with studying the Church’s teaching on artificial birth control. On April 28, 1967, Time magazine carried the bold headline, “Catholic Bishops Assail Birth Control as Millions Face Starvation.” Below the caption was an empty bowl held outstretched by a hand labeled “Hunger.” Such a blatant and misinformed mockery of the Church opened the door to a whole new level of assault on Christian morality. Today, there is next to no respect for the value of the Church’s teaching in the media, government, and entertainment.

We, as a Church, did not help ourselves either. The 1960s were a time of cultural upheaval, a dangerous time to hold an event so critical and life-changing as an ecumenical council, and the Church did not adequately prepare herself for the task of proclaiming the Gospel in such unsettling circumstances. The result was the lack of a cohesive vision. The faithful began to hear different interpretations of Church teaching depending on the parish or university they attended. While there will always be room for legitimate discussion, and while the university is permitted some degree of academic freedom to expose new ideas and theology, the 1960s saw the beginning of a climate of dissent in which theology was divorced from the doctrine at the heart of the Church. In reaction to the publication of Humanae Vitae, a statement was drafted on July 30, 1968, in Washington, D.C., and signed by 87 theologians, protesting the papal document and seeking support.9 From then on, it has been commonplace for one to remain in the Church and publicly disagree with significant moral teachings without feeling a bit pharisaical. It was within such a climate of media bias and dissent, that Pope Paul VI, with his vast expertise and deep faith—mingled with personal limitations—exercised leadership over the Church and brought the Council itself to a close.

In their deliberations over the selection of a new pope following the death of John XXIII, Montini was a known entity for the voting cardinals, because of his long history within the Vatican in several positions. Specifically, as pro-Secretary of State under his predecessor Pius XII, who maintained a merely formal and ineffective approach to the ad limina visits, it was Montini who took the time to meet with the bishops of the world, read their reports, and understand their concerns.10 Robert A. Ventresca, in his biography of Pius XII, Soldier for Christ, describes a Vatican culture of “inertia, stagnation, and reaction,” open to theological dialogue, but then condemning new approaches.11 He also shows how heavily involved Montini was in discussions with cardinals and bishops over the most serious affairs of Church and world affairs.12 After his service to the Vatican, he was appointed archbishop of Milan. Because of his experience as both a Vatican official and a pastoral leader, Montini grasped the bigger picture of needs and problems within the Church. He had a number of qualities that made him an outstanding papabile in 1963. He had proved himself as a “fine administrator,” “brilliant diplomatist,” and priest, rooted in the faith and culture of the Church. Amid pressure by the media to exaggerate the popular response to the death of John XXIII, and, thus, put pressure on the conclave to choose a pope who would fill his mold, there was a consensus that the Church needed a “moderate” figure “with great diplomatic skill and thorough understanding of the problems of the Church”13 to reconcile opposing camps, and exercise restraint over the continuance of the ecumenical council. As one prelate at the time said of the cardinals,

They all agreed that Pope John had performed a prodigious and necessary service by stirring the Church up, setting it on the march again. Nevertheless, a great number of them felt that this work had been interrupted at the right time, that any further surge forward would have carried the Church into practically unsustainable positions, or would have forced it to swerve too far from its historical lineaments and de-catholicize itself most imprudently.14

Montini had the skill and experience to take the reins of the Church, amid an experience as monumental as an ecumenical council, and steer her prudently, amid a variety of pressures from within and without. Just as there were progressives at the time of Paul VI who wanted him to be a pope in the image of what they imagined John XXIII to be, there are individuals, today, who, influenced by secular ideas, lament that the Council did not go far enough, did not de-Catholicize herself sufficiently. The key here is to recognize that the cardinals were guided by the Holy Spirit to come to a consensus in choosing a disciplined leader whose papacy would keep the Church true to herself while speaking to the times. The opening of a Second Vatican Council was a long-awaited event, ever since First Vatican Council was suspended because of the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. Good Pope John saw his papacy as the right time to reconvene the bishops and seek necessary reforms, particularly, to canon law. This deeply spiritual man would not have envisioned a wholesale reimagining of the Church.15 As various factions tried to capture both John XXIII and Paul VI for their own agendas, Paul VI remained true to the heart of the Church.

An authentic portrayal of Pope Paul VI reveals that he was his own man, not easily pigeon-holed into the ideologies of right or left, and always displaying the tradition of Catholic faith, in which his whole life was rooted. We will see this more clearly when we examine his writings. As with every human person, he also had some weaknesses that played into his experiences as pope. John H. Knox wrote in 1969, describing an observer’s view of Paul VI’s temperament.

He is an intelligent, sensitive, introspective, high-minded, patient, and well-trained man. He is also well-informed, austere, modest, industrious, timid, and indecisive. He shrinks from making irrevocable decisions, and, like most who do, find it easier to say yes, than no. His vacillation comes from a reluctance to accept responsibility. Like many professional diplomats, he thinks he can attain almost any goal by patient negotiation and flexibility.16

This temperament manifested itself in a reluctance to make strong statements commanding fidelity to doctrine or condemning dissent, which would be falsely interpreted as ideologically motivated. He was not a “leftist.” He just “never orders his teaching to be accepted, but merely recommends it. There are no penalties for disobeying it or even for repudiating it publicly.”17 While in his speeches and writings, he often displayed a sincere commitment to the Catholic faith and a desire for it to be embraced, he did not hold others to task for infidelity, and avoided, at all cost, the anathemas and excommunications of previous ages. There is tremendous good in a pastorally sensitive approach, and in proposing, rather than imposing. However, ambiguity does not help to further the cause of evangelization. Paul VI showed a “refusal to act against any individual” in his role as pope, preferring instead “deploring the error or misconduct, sometimes tearfully,” being “always careful to attribute only high motives to all the erring, whom he never identifies.”18 That was as far as he was willing to go. He was not comfortable with absolutes and condemnations in teaching the doctrines that were indispensable for him personally. The result was that “people in good standing in the Church attack her fundamental doctrines with impunity,” and the public perception was that “The Holy See will do nothing.”19 Surely, there were other factors that played into the climate of dissent that began after the Council, and it is a bit harsh to claim he did not want to accept responsibility for the Church, yet one has to wonder how much Paul VI’s own personality, unbeknownst even to himself, affected the entire Church.

Taking a look at the big picture at 50 years’ distance from the events themselves, it is now obvious that some of the changes in the Church, particularly, the most visible ones for the faithful that occurred in the liturgy—the un-called-for removal of Latin and Gregorian chant, the de-sacralizing of liturgical prayer in the original vernacular texts, and the obliteration of the sacred in liturgical architecture that accompanied the push for Mass versus populum—were undertaken without any basis in the Council documents, and were an inorganic rupture in the trajectory of Church tradition.20 It is arguable that such problematic changes happened without the direct knowledge of Pope Paul VI, who presumed the best motives of those around him and avoided the confrontation that would be involved in micromanaging the implementation of the liturgical reform. One anecdote illustrates what could have happened if Paul VI’s methods were taken advantage of by the advocates of deconstruction:

Some years ago … gosh, it was decades now … I was told this story by a retired Papal Ceremoniere (Master of Ceremonies) who, according to him, was present at the event about to be recounted. You probably know that in the traditional Roman liturgical calendar, the mighty feast of Pentecost had its own Octave. Pentecost was/is a grand affair indeed, liturgically speaking. It has a proper Communicantes and Hanc igitur, an Octave, a Sequence, etc. … The Monday after Pentecost in 1970, His Holiness Pope Paul VI went to the chapel for Holy Mass. Instead of the red vestments, for the Octave everyone knows follows Pentecost, there were laid out for him vestments of green. Paul queried the MC assigned for that day, “What on earth are these for? This is the Octave of Pentecost! Where are the red vestments?” “Santità,” quoth the MC, “this is now Tempus ‘per annum.’ It is green, now. The Octave of Pentecost was abolished.” “Green? That cannot be!” said the Pope, “Who did that?” “Holiness, you did.” And Paul VI wept.21

Precise knowledge of exactly what happened within the Vatican in those days remains unattainable, buried in the shadows of history. For sure, what erupted in the 1960s was confusion among the faithful over Catholic doctrine and liturgy, rather than clarity.22 A breakdown in Catholic consistency, rather than an exciting age of evangelization, emerged in the years after Vatican II.

Writing six years after the close of Vatican II, in 1971, Charles E. Rice identified a “crisis of authority” in the Church. The shocking title of his book, Authority and Rebellion: The Case for Orthodoxy in the Catholic Church, revealed how far afield many Catholics had gone: suddenly we needed to make a case for orthodoxy in the Catholic Church! In a most important distinction, reviewer Will Herberg reminds us that “the questioning of authority comes not from the council, but from the ‘liberal’ Catholic attempt to present the council under the aspect of aggiornamento. But aggiornamento (bringing up to date) is simply the slogan by which these Catholic ‘liberals,’ who have long chafed under the rigor of Church discipline, have been striving to overthrow the authority of their Church. …”23 The fatal flaw, hidden within the excited frenzy, was embracing aggiornamento without the complementary theological principle at work in the mid-20th century, ressourcement, a “return to the sources,” through a new appreciation for the common fountain of wisdom in the Church: the centrality of the person of Christ, the Scripture, the Fathers of the Church.24 Both aggiornamento and ressourcement realize their full potential and effectiveness when in harmony with each other. Any truly effective attempt to update the Church’s proclamation of the Gospel must be rooted in, and preceded by, a thorough examination of the sources from which she emanates. The documents of Vatican II are so rooted. As the conservative and progressive factions in the Church both imagined their own sources in the absence of an exploration of the authentic ones, ensconcing themselves unwaveringly in the texts of Trent or those of avant garde theologians, Pope Paul VI “made valiant and, on the whole, not ineffective efforts to stem the tide and check the forces of dissolution, but the crisis still remains.”25 Indeed, it does, even to today, whenever Catholics speak and act divorced from the roots of Catholic doctrine. The Church continually responds to the times, but only effectively and with credibility, when she remains true to herself.

All of the dissent among scholars, infighting among bishops, and confusion among the faithful took its toll on Pope Paul VI. In 1969, William F. Buckley wrote of “the agony of Paul VI” and of the pope “lamenting the disintegration of Catholic unity.”26 In a message released during Holy Week of that year, Paul VI “spoke of a ‘practically schismatic climate (which) divides (the Catholic community), breaking it into groups …’… And he asks whether the Church is still ‘truly animated by that sincere spirit of union and charity,’ such as to permit its flock to observe without hypocrisy ‘our most holy daily Mass.’”27 That is a searing indictment from the Holy Father. Such a crisis, as observed by Buckley, magnified dissatisfaction within the Church, and even disturbed much of the non-Catholic world. Rome could no longer be trusted to preserve dogmatic Christianity, so it seemed. Reflecting on both doctrinal disintegration and the experience of the “aesthetic ordeal” within the reformed liturgy, Buckley concluded that “the common denominator between the two problems is loss of standards: doctrinal, aesthetic. The Catholic Church has been historically the tablet-keeper. The surrendering of its convictions at so many levels is a cause of the sorrow of Paul VI and of so many of his flock.”28 The Church surrendered its convictions in order to be more accessible to popular culture. The pope observed what was happening in the wake of the Council, agonized, and then mustered the courage to teach definitively on the essentials of Catholicism.

It would not have come easily or naturally to Montini to take on the forces he perceived were manipulating the “spirit” of the Council and weakening the integrity of the Church. Yet, as pope, he knew he had to stem the tide of dissolution, which he believed to be no less than the work of the Evil One.

In 1972, on the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul, Pope Paul VI delivered a sermon that startled the world. Describing the chaos, then consuming the post-conciliar Church, he lamented: “From some fissure, the smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God.” Paul’s words were a warning to all who, taken with the “spirit of Vatican II,” “rather than the Council’s actual teachings,” had fallen under the sway of dark spirits.29

It does not get any clearer than this: the “spirit” of the Council, in the words of Paul VI, was not the official teaching of the Council. Even more serious than Benedict XVI’s description of it as an agenda or media fabrication, the “spirit of Vatican II” for Paul VI was influenced by evil. He knew something had to be done.

The churchman Montini emerges in the writings of Pope Paul VI, which touch on the major areas of Catholic teaching: the Creed, liturgy and sacraments, and morality. In the Credo of the People of God, he reiterated all the fundamental doctrines about God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, Mary, and the Church in language accessible to modern people, and suited to the spiritual crisis of the times. In the encyclical Mysterium Fidei, he began with the Council’s reaffirmation of the Church’s beliefs regarding the Eucharist, addressed contemporary disturbing opinions and pastoral anxieties, and then proceeded to promote, with the greatest authority, devotion to the Eucharist in Mass, Eucharistic Adoration, and frequent visits to the Blessed Sacrament. In the greatest challenge of his papacy, he set aside the recommendation of his own papal commission on artificial contraception and affirmed the inseparability of the unitive and procreative dimensions of the marital act in Humanae Vitae. This is the work of a man who knew and understood what the Church is about, and set his heart and pen resolutely on proclaiming the Gospel authentically.

Pope Paul VI and the Second Vatican Council are historically intertwined. He concluded the Council, and then he began to implement it. For some, neither went far enough; for others, both went too far. That is not a debate that will soon be silenced. The times in which the Council took place, and in which Paul VI reigned as pope, were characterized by a confluence of pressures: cultural upheaval, the “council of the media,” scholars making open challenges to established teachings, the various interpretations of the “spirit of Vatican II,” and the tension of disparate expectations of the pope by those on the left and right. Pope Paul VI was a man of intelligence and administrative skill, committed to the heart of the Church. He was chosen to bring moderation and discipline at the moment Vatican II was interrupted by the death of John XXIII, lest the Church wander farther from her foundations. In response to that call, he shied away from the anathemas that would have clarified doctrines, but also likely would have caused alienation among Christians, and added to the sensationalism the dissenters would have enjoyed promoting in the press. Instead, overcoming his weaknesses, he took up the mighty pen and wrote definitively on the most essential aspects of Catholicism, as it encountered the modern world. For this and more, he is, indeed, worthy of our admiration. As we study what he taught and how he lived, we discover his legacy of commitment to the authentic Church, amid a whirlwind of conflicting ideas. Only such an approach will maintain the Church’s credibility as the guarantor of the truth. This ought to be the modus operandi of the Church in this historical moment, in between the extraordinary and ordinary synods, as she discerns how to meet the needs of families, the primary locus of the new evangelization, and effectively form them in the ways of God.

- Moats, Alice-Leone, “The Riddle of Pope Paul VI,” National Review (October 22, 1963): 347. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- He did so despite the fact that it had been made clear that Vatican II was never established with the intention of changing doctrine. John XXIII clearly stated in his opening speech that the council was to be “predominantly pastoral in character” and focused on the Church relating effectively to the modern world, since “she must ever look to the present, to the new conditions and new forms of life introduced into the modern world, which have opened new avenues to the Catholic apostolate.” At the same time, the council was to “to transmit the doctrine, pure and integral,” for “the Church should never depart from the sacred patrimony of truth received from the Fathers.” According to the hermeneutic of continuity, Vatican II and Paul VI are the inspired links in an organic history of the Church. ↩

- McBrien, Richard, “Popes of the 20th Century: Paul VI,” National Catholic Reporter (Aug. 23, 2010) ncronline.org/blogs/essays-theology/popes-20th-century-paul-vi ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- By the way, the Missal had already been adapted by Pius XII in 1955 and John XXIII in 1962, so there is certainly precedent for organic development in liturgy and papal reform. ↩

- Benedict XVI, “The Second Vatican Council As I Saw It.” February 14, 2013. en.radiovaticana.va/news/2013/02/14/pope_to_rome%27s_priests:_the_second_vatican_council,_as_i_saw_it/en1-664858 ↩

- See Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s address to the Roman Curia, Christmas 2005. ↩

- See Hardon, John A., SJ. In Defense of Humanae Vitae. therealpresence.org/archives/Faith_and_Morals/Faith_and_Morals_003.htm ↩

- Moats, “The Riddle of Paul VI,” 347. ↩

- See: Ventresca, Robert A., Soldier for Christ: The Life of Pope Pius XII. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013) Kindle locations 3493-3983. ↩

- Ventresca, Soldier for Christ, Kindle locations 4312-5260. ↩

- Moats, “The Riddle of Paul VI,” 348. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See the following book review: Van Hove, Brian, SJ, “Common Myths About Three Catholics,” a review of Dr. America: The Lives of Thomas A. Dooley, 1927-1961 by James T. Fisher, Homiletic and Pastoral Review, vol. 108, no. 2 (November 2007): 56-59. frvanhove.wordpress.com/2008/11/28/dr-america-the-lives-of-thomas-a-dooley-1927-1961/ ↩

- Knox, John H, “The Pope as Hamlet,” National Review (October 21, 1969): 1059. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Knox, “The Pope as Hamlet,” 1058. ↩

- Knox, “The Pope as Hamlet,” 1060. ↩

- N.B. Reform was needed but organic, gradual and pastorally sensitive reform undertaken with proper catechesis would have been far more effective in stirring the renewal within the Church for which the bishops longed when they embarked on the work of the Council. ↩

- See Zuhlsdorf, Reverend John. “A Pentecost Monday Lesson: ‘And Paul VI Wept.’” July 9, 2014. At Father Z’s Blog wdtprs.com/blog/2014/06/a-pentecost-monday-lesson-and-paul-vi-wept-2/ ↩

- To many people inside and outside the Church, it appeared that the reforms being advocated by progressives were not flowing from the heart of the Church but smacked of a different religion. “Professor Jeffrey Dart of Dartmouth, a recent convert to Catholicism, wrote recently why the left-wing (so-called) of the American Catholic Church does not do the obvious thing: namely embrace some form of Protestantism.” See Buckley, William F, “The Agony of Paul VI,” National Review (May 22, 1969): 403. ↩

- Herberg, Will, “A Crisis of Authority,” a review of Authority and Rebellion: The Case for Orthodoxy in the Catholic Church, by Charles E. Rice, National Review (October 22, 1971): 1183. ↩

- See D’Ambrosio, Marcellino, “Ressourcement Theology, Aggiornamento and the Hermeneutics of Tradition,” Communio. 18 (Winter 1991). crossroadsinitiative.com/library_article/54/Ressourcement_Theology__Aggiornamento_and_the_Hermeneutics_of_Tradition.html ↩

- Herberg, “A Crisis of Authority,” 1183. ↩

- Buckley, “The Agony of Paul VI,” 402. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Buckley, “The Agony of Paul VI,” 403. ↩

- Doino, Jr., William, “The Smoke of Satan Returns,” First Things. (October 28, 2013). firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2013/10/the-smoke-of-satan-returns ↩

But was the Missal and the Sacramental Rites promulgated by Paul VI actually in clear continuity with the past? The reforms to the Mass undertaken under Pius XII (Holy Week) and John XXIII were minor compared to what happened under Paul VI. The new Mass, while certainly valid, is completely fabricated, its not just a revision bit a total rewrite.

Mysterium Fidei is a good encyclical as is Humanae Vitae but I’m not confident the New Mass was a grave mistake. It cut us off from the Orthodox and even from traditional Anglicans and traditional Lutherans so radical is its praxis and its fabricated lectionary. There’s nothing in history in either east or West quite like it.

It’s neither fabricated nor a rupture if celebrated properly, with Latin elements, ad orientem and according to ancient forms. Visit the Society of Saint John Cantius in Chicago for a Novus Ordo Mass. (One could debate the offertory prayers but the two forms do not look starkly different if the NO is celebrated well.)

Father Albright, thank you for this wonderful paper on Paul VI . I was in Rome 1976-77 and saw Paul VI at mass in the Lateran cathedral for the Rome diocese CCD. 1977 . He was the only Pope I ever saw . And there were priests and so called theologians who forgot about the Papal magisterium and the Extraordinary episcopal magisterium and the Divine Presence of the Holy Spirit and Jesus apostolically teaching us that he is with the Church forever . The Holy Spirit and Jesus saying whatever is loosed by that authority is also loosed in heaven and whatever is decided by that authority is also done in heaven. The doctrine of papal teaching on subjects of Moral theology, virtue or sin and doctrine infallibly exists with the Holy Spirit and the Pope. This is a most beneficial doctrine for we who believe. Father Albright I am a 4th degree member of the Knights of Columbus Abram J. Ryan assembly and council 11937 St Thomas Aquinas Dallas

Also the present mass in English, the Nicene creed and Scripture are perfect translations and easy to recite or read. Here in Dallas at my parish St. Thomas Aquinas I am a lector and EM. And I have a licentiate in Theology and Scripture from the University of Dallas and St. Mary’s seminary. Mo. 2003.