- Can you tell me what the origin is of our rights and how this relates to the laws of the state?

- Pope Francis recently caused a reaction in the United States by condemning “unfettered capitalism.” Is this an innovation in Catholic thought?

Question: Can you tell me what the origin is of our rights and how this relates to the laws of the state?

Answer: The question of the origin of rights is an important one for determining the basis for the virtue of justice. Justice is defined as the “constant and firm will to give their due to God and neighbor” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1807). The “due” in this definition is what is classically meant by a right. Rights are about others, not the self. Rights become important when other people are involved; when something is due them; and when it is possible to restore to the other what one ought to give him.

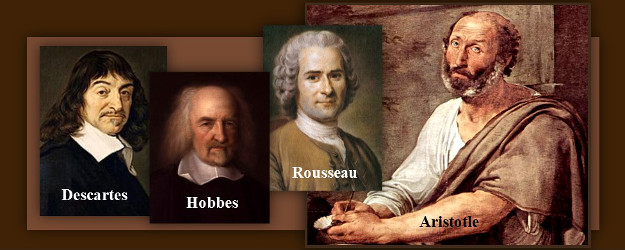

Since the 16th century when European philosophy became preoccupied with subjectivism as a result of Descartes’ famous “turn to the subject,” the question of the origin of rights in society has been difficult. Prior to this, Aristotelian philosophy and the Catholic thinkers who made use of it were clear that the origin of rights was in human nature. It was the reasoning nature of man characterized by the spiritual soul in a human body which was the source of right. Since man transcended matter, there was something untouchable about the human person.

Also, since the basis for rights was the objective nature of man, the virtue of justice on which it was based was realized in giving rights to others. This is the origin of the famous idea in Plato that it is better to suffer than to do injustice. A person who suffers injustice loses something physically. But a person who does injustice suffers some spiritual lack.

With the dawn of modern European philosophy, the whole idea of substance and objective universal nature was brought into question. The most prevalent fruit of this in politics was the origin of the so-called Social Contract theory of society, and thus, the origin of rights. The two thinkers most involved in the propagation of this theory, Hobbes and Rousseau, taught that human beings were not natural members of society. They did this for different reasons. For Hobbes, the need for society was created by his belief that men were naturally vicious, the war of all in all. Society was founded by the free will of men to save them from destruction. For Rousseau, men were noble savages who, because of the development of property, were led to competition, and so to strife. His social contract was also a plank to which natural men, “shipwrecked by property,” clung by their own will. These were the Social Contracts.

In either case, it was society which gave rights to people. The sovereign was the origin of justice, whether he was a king, noble, or democrat. The social contract creates rights. The title to rights was created by society. So, the title to have the right to life is defined and granted by society. The human will creates right and justice and can just as easily deny them.

The Catholic answer to this is to say that there are two origins of the title to rights: natural and positive. The former is objective and universal. Though society may determine how to ensure the practice of these rights, they are not established by the human will, but rather by the soul of man and his spiritual nature. Positive right is created by the human will. However, that positive right truly guarantees justice; it cannot grant or deny title to any right which is contrary to natural right. Rights also have duties which demand the respect for the rights of others. When the origin of right is placed merely in the human will, this naturally leads to the idea that might makes right, whereas the Catholic solution is that might must implement and serve the right.

Question: Pope Francis recently caused a reaction in the United States by condemning “unfettered capitalism.” Is this an innovation in Catholic thought?

Answer: This supposed statement of Pope Francis in the recent Apostolic Exhortation, Joy of the Gospel, has caused great rejoicing on the part of liberals and great distress on the part of conservatives in the United States. The problem is that Pope Francis never said it.

In the Apostolic Exhortation, the only statement which comes close to this is: “Today’s economic mechanisms promote inordinate consumption, yet it is evident that unbridled consumerism combined with inequality proves doubly damaging to the social fabric” (n. 60). The Pope was lamenting the fact that this consumerism leads to violence and many people being marginalized who cannot compete. The only reference to capitalism in this context is to one theory of economic growth.

In this context, some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting. To sustain a lifestyle which excludes others, or to sustain enthusiasm for that selfish ideal, a globalization of indifference has developed. Almost without being aware of it, we end up being incapable of feeling compassion at the outcry of the poor, weeping for other people’s pain, and feeling a need to help them, as though all this were someone else’s responsibility and not our own. (n. 54)

It is true the Pope believes that the trickle-down theory of capitalism (which maintains that the simple fact of the growth of companies will produce economic prosperity) is inadequate. This is, after all, only one theory of the free market and is a far cry from the condemnation of the free market, as such, and advocacy of socialism and state ownership, of which he was accused. In fact, in this teaching, Pope Francis was merely reflecting the common social teaching of the Church since Pope Leo XIII, which holds that pursuing any doctrine of wealth in which profit is the only motive, and having confidence that this will automatically lead to prosperity, is not only elusive, but also not common sense.

The Catholic social tradition has always favored a middle approach between unbridled capitalism, or consumerism, and the radical socialism of Marxism. The Church has always insisted on the right to private property, but this right has both an individual and a social dimension. Wealth exists to serve the common good through development. This should occur in things like providing goods and services, just wages to support a family, and maintenance of the economy. A free market is an excellent way to do this, provided it is not seen as an end in itself, with no outside standard by which to judge the just manner in which the market is carried on. Liberal capitalism, which is related to what the Pope means by unbridled consumerism, sees property as a source of wealth but with no further responsibility to develop that wealth for the good of man.

The alternative solution to this, always rejected by the popes since Leo XIII, is state ownership and redistribution of wealth, in which the right of property is denied to anyone but the collective. This is characteristic of radical socialism, Marxism, and totalitarianism, in which the individual becomes beholden to the collective and has no freedom or liberty to develop its resources. Here, there is no property, and so, wealth has only a social dimension, and, thus, no individual dimension. The citizens all become wards of the state, and though they may be well fed and happy, have no true liberty of action. They are total dependents.

The solution of the Church has always been a middle ground, affirming both the rights and duties attendant on property. The state has a role in the creation of wealth, but only by encouraging and regulating private enterprise, regarding its rights and duties. The purpose of property and wealth distribution is not a forced disbursement at the hands of the all-powerful state, contrary to basic rights. Instead, it is a kind of profit sharing, in which labor acquires an interest in capital, and so, through political and economic freedom, also shares in the rights and duties of the social and human development of wealth. Bishop Sheen put this well in a work he wrote during the Great Depression, Freedom Under God.

By private property here, we do not mean principally consumable goods such as rented house, food, clothing, and automobile, but rather productive wealth, e.g., his own farm, cooperative enterprises, or a share in the management, profits or ownership of industry. It would seem today that labor is satisfied only with created wealth; not creative wealth; with consumptive wealth, not productive wealth. (p. 38)

What Pope Francis is calling for in Catholic evangelization is to encourage Catholics and society in general not merely to pursue profit in the pursuit of wealth. Nor does he call for denying the right to property as such. Rather, he is calling on corporations, and, indeed, developing nations, to evaluate anew their theories of wealth, and recognize that leading individuals, through work, to participate in creative wealth and productive wealth is the only way to guarantee true liberty and peace in contemporary society.

Recent Comments