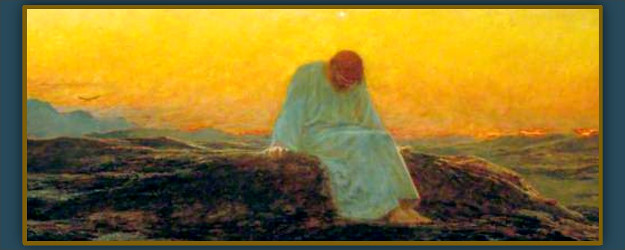

The Temptation in the Wilderness, by Briton Riviere (1898).

Sacrifice is troublesome for us fallen humans. It is not only the inconvenience or effort that troubles us so much, because we are sometimes willing to be inconvenienced or troubled for good reason; that is, a reason that serves our own agenda in some way. The need to sacrifice may become palatable when it can be connected with some form of personal advancement or gratification. The most difficult part of truly understanding sacrifice, in a religious sense, comes from our unwillingness to admit that we owe anything to anyone other than ourselves. We are consistently taught by our society, in all places, from kindergarten to Madison Avenue, that our purpose in life is to achieve, become, and grasp at whatever makes us feel best about ourselves. Adam and Eve, even without public school or mass media, found themselves unable to resist the temptation to do some grasping themselves, looking for something more, and novel, even while in the midst of paradise. The understanding that they owed something to God and were called to return the gifts he had given them, though built into their very nature, was found to be less than compelling or binding in the end.

Sacrifice requires a willingness and ability to prioritize our lives: to rank our obligations and to properly order our desires. To sacrifice a “thing” for something else, whatever the sacrifice itself, or its purpose, may be, is to say that the purpose supersedes the object. To sacrifice something, specifically to a higher power, is to say, “this thing is less important to me than you.” For this reason, it is easy to see the natural place of sacrifice in the cult of religion as an antidote to our concupiscence and selfishness. In the context of biblical religion, animal sacrifice (such as the sacrifice demanded by God from Abram to initiate the Genesis 15 covenant) has the additional significance of the shedding of lifeblood—signifying the participant’s agreement to have the same thing happen to him if he is unfaithful to the covenant. It was, for the people Israel in the Old Covenant, a regular reminder of the grave implications of their chosen status.

God’s prescription for sacrifices is taken up a notch when we get to Moses and the Exodus. The Passover lamb reveals to the Hebrews something new about the power of sacrifices. The Hebrews were instructed by God through Moses to procure for themselves a sacrifice, which would be offered to God as a sign of the covenant, a relationship which would ensure their safety from the impending death of the opposed world. The unblemished lamb’s death, sealed by a ritual marking (blood on doorposts and lintel of Hebrew homes) and consumption of its flesh, prevented the death of the Hebrews; a death which would be experienced by everyone outside of the Hebrew family (i.e., the Egyptians). Those who participated in the Passover covenant recognized that the lamb was not intended as merely a reminder that death was the consequence if they failed to honor the covenant, but, instead, was a sacrifice that spared them from a death that they deserved and would have otherwise justly received. Often, in our reading of the Plagues, we wrongly assume that only the Egyptians were guilty of ungodliness, but this certainly does not seem to be the case, both from our general recognition of universal original sin, and also, specifically, by later indicators in the Exodus story (e.g., the idolatry of the Israelites with the Golden Calf in Exodus 32, not to mention their continuously voiced preference for their lives in Egypt to their newfound experience under the leadership of Yahweh). The Passover lamb becomes a death of substitution for the Hebrews. The lamb dies so that the chosen do not have to. In effect, the lamb is the one that makes good on the promise of Abram who staked his life on the covenant with God in Genesis 15. The Beloved Disciple goes out of his way to make sure his audience understands that Jesus himself is the fulfillment of the Passover lamb (see John 1:29, 19:14, 19:29, 19:33); that he has come to die so that we might live; the one who makes good on our promises and accepts the consequences of our disobedience. Psalm 51 portrays a more developed understanding of the effect of the sacrifice of the Lamb (“Cleanse me with hyssop, that I may be pure,” verse 9). The reference to hyssop, the specific type of stalk which Moses prescribed to be used in applying the blood of the lamb to the lintels and doorposts—which the fourth Gospel also records as the instrument used to raise the final cup of wine to the lips of Jesus on the Cross—foreshadows the fact that participation in the New Covenant enables not only substitution, but sanctification.

The classic Western view of Atonement, largely based on Anselm of Canterbury as recorded in his classic work, Cur Deus Homo, emphasizes the fact that Jesus died as satisfaction for our sin. In other words, the transgressions of humanity necessitated a payment to be made in order for the debt of sin to be forgiven. Humanity owed God obedience, yet failed to give it to him. Original sin, and all sin which follows it, constitutes a failure not only to give back to God what he has given to us as our creator, but is also a refusal to honor the agreement which had been made by our forefathers on our behalf; an agreement offered to us by God for our own benefit, not his. That overdue, unpaid debt continued in its delinquency until the Incarnation. By lowering himself to take on human flesh, God shows that his willingness to offer us a share in this covenant will not stop at fulfilling his obligations—he will fulfill our part as well. Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity, is the one who pays this debt through his self-surrendering crucifixion.

For Anselm, it is necessary for man not only to repay the original debt, but, in fact, to go beyond, in order to satisfy both the original demand of obedience naturally accorded to God by his creatures, and the deficit created by prior failure to fulfill this standing obligation. According to Anselm, “So long as he does not pay that of which he has robbed him, he continues in his fault; and it is not enough to restore to God only what he has taken away, but he ought also, to make amends for the insult done to God, to restore more than he took away.”1 In other words, humanity has always owed God perfect obedience, but man has already sinned against him; therefore even perfect obedience (which we know is impossible due to our fallen nature, but consider it hypothetically for the sake of logical argument) would be insufficient because it still would not make up for original sin. To use a mortgage analogy, all we can ever do is hope to continue paying off the interest, but can never cut into the principle. Anselm is simply pointing out what is obvious and logical in any debt/payment scenario: if giving everything you have will not satisfy a debt, you have no hope of settling it, based on your own power. To Anselm, Jesus was the only one capable of making the necessary atonement because he alone did not owe an additional payment. “It was fitting that we should have such a high priest; holy, innocent, undefiled, separated from sinners, higher than the heavens. He has no need, as did the high priests, to offer sacrifice day after day, first for his own sins, and then for those of the people; he did that once for all when he offered himself” (Hebrews 7:26-27). Anselm asserts that Jesus’ handing over of his life was “a debt God would not require of him; for since there is no sin in him, he will be under no obligation of dying.”2 Jesus is able to pay off the debt precisely because he did not owe it in the first place.

The question is, then, how exactly did Jesus pay off this debt? If we believe that Jesus offered himself as a sacrifice to fulfill an obligation, we ought to try to come to some understanding of the true nature of that requirement. The historical culmination of Jesus’ sacrifice, the tortuous death of crucifixion, leaves us with a very physical feeling about sacrifice. His sacrifice was clearly a physical one, but was the physical component of his sacrifice the one that was most necessary or the one that made it effective? Although we must recognize the sacrificial nature of the Passion, we should not view Jesus’ death on the cross simply as a physical offering made as appeasement to God for sin. If the debt owed by humanity for the guilt of sin is physical suffering of the type Christ endured for us, are we to say that God the Father desired that we, as individual humans, be crucified, but that Jesus, either willingly, on his own part, or out of submissive obedience to the Father, accepted this penalty so that we did not have to? This line of thinking clearly does not make sense in light of our understanding of the eternal and spiritual significance of the guilt of sin, nor is it consistent with the Christian understanding of the divine nature. The penal substitution model remains a meaningful framework through which to interpret Christ’s Passion. However, the emphasis should be primarily on the metaphysical implications of Christ’s self-emptying gift and its soteriological significance.

Hans Urs von Balthasar shares much in common with Anselm in his understanding of the need for satisfaction to be made for sin to enable man to be restored in relationship with God. Particularly in two of his works, Myterium Paschale and Dare We Hope That All Men Be Saved, Balthasar uniquely emphasizes the spiritual burden which Jesus willingly bore for the sake of mankind’s redemption. For Balthasar, this act of self-emptying and acceptance of mankind’s dejected state was the necessary and divinely willed means of rescuing man from God-forsakenness. In his sacrifice, Jesus both paid our debt to God (total obedience), and accepted the punishment that we incurred through that debt. The punishment due to us was a natural consequence of our disobedience: in turning away from the beatific vision, we automatically turned towards God-forsakenness. And we did so by our own free will, not as a punishment from God. Balthasar emphasizes the degree of kenosis (self-emptying) required in order for God to take on this debt and satisfy it on our behalf. In order to accomplish this rescue mission, God did not just send a lifeline to man from a distance while remaining invulnerable himself; instead he willed a total condescension in which he accepted the fallen status of humankind. According to Balthasar:

Looking at this from the divine perspective, if God wished to experience the human condition from within, so as to redirect it from inside it, and thus save it, he would have to place the decisive stress on that point where sinful, mortal man finds himself “at his wit’s end.” And this must be where man has lost himself in death without, for all that, finding God. This is the place where he has fallen into an abyss of grief, indigence, darkness, into the pit from which he cannot escape by his own powers.3

Balthasar notes that the depiction of the Agony in the Garden and Jesus’ words from the Cross show us that Jesus’ most extreme suffering comes from the anguish of fear and isolation which anticipates his death, not from his physical experience on the Cross. Balthasar goes so far in emphasizing the overwhelming grief Christ experienced as to suggest that Jesus truly feared being cast into hell, and that his prayer of supplication on the Mount of Olives was his only certain means for salvation.4

In his emphasis on Christ’s passive descent into hell, Balthasar challenges the Christus Victor model which seems to suggest an active descent in which Christ, while appearing dead in his humanity, was actually triumphantly furthering his mission in an unseen dimension. In his Confessions, Augustine emphasizes the triumph and control of Jesus’ Passion by saying, “He had the power to lay down his soul and power to take it back again. For us, he was victorious before you and victor because he was victim.”5 According to the “Christus Victor” model, Jesus descended with power and authority; forcefully smashing down the gates of hell, forcing the devil into submission, and freeing those souls who had been held captive. In this view, Jesus did not suffer in hell. It could be said that this victorious Christ descended as the Glorified Christ, rather than as the Jesus who was betrayed, tortured, forsaken, and executed. When viewing this model, we get the impression that hell was not even a stopping place for Jesus; he comes, he frees, and he takes the souls of the just with him to heaven without spending any time there and without having any meaningful experience of hell.

This model has implications for the question of how Christ truly atoned for our sins in that it seems to suggest that Jesus’ bearing of our sins was in some way a less than full acceptance of our guilt and its corresponding punishment. Support for this model can be found in Cyril of Jerusalem, who said of Jesus that, “He came therefore of His own set purpose to His Passion, rejoicing in His noble deed, smiling at the crown, cheered by the salvation of mankind; not ashamed of the Cross, for it was to save the world.”6 While Jesus never sets aside his identity as God in his Incarnation, there is Pauline evidence that his becoming man involved a real lowering of status that went beyond his mission and actually affected the personal aspect of his nature. When Paul wrote to the Philippians of Jesus’ “taking the form of a servant” (Phil 2:7), he was writing to a Roman culture which was very familiar with slavery and its implications.

In his book on the social history of the Roman Empire, Paul Veyne notes that, in the Roman Empire, a slave was considered an inferior being by nature, a barrier which was believed to be impregnable.7 According to Veyne, “it was indecent to point out that a slave had been born free and sold himself into slavery, indecent even to speculate about the possibility that a free man might sell himself in that way.”8 Veyne notes that this perceived separation of nature was so vast that even if a child born of a slave were truly the flesh and blood of the master, “it was unthinkable that a master would scheme to recognize a slave as his own son.”9 Even if a master did desire to show favor to the child and elevate his lot in life by freeing him, he would do so without admitting the true reason for his favor, which would betray his true paternal connection with the slave. In fact, even after manumission, the master was forbidden by law to recognize or adopt the child.10 Considering these cultural factors at work in the literal sense of the New Testament, it seems difficult to suggest that the Incarnation and Passion of Jesus were primarily characterized by triumph and dignity in Jesus’ experience.

The classic understanding of Christ’s triumphant descent into hell also seems to emphasize the physical sacrifice on the Cross to the possible neglect of the metaphysical “God-forsakenness,” evident in the Passion accounts. This interpretation of Christus Victor suggests that Christ, though truly enduring the suffering of the Cross, did so while maintaining unwavering confidence in the knowledge of his impending rescue and subsequent glorification throughout his Passion. In opposition to the opinion that Jesus enjoyed a sense of victory during his descent, Balthasar asserts that Christ’s objective interior victory was not subjectively experienced as such, for this sort of triumphant state would have compromised his solidarity with sinners.11 However, it must be noted, that it could be argued that the Christus Victor idea does fully recognize the spiritual separation between the Father and Son, though only experienced in his mission and Passion leading up to his sacrificial death, and not extending past it. In this way, this model seems to focus exclusively on the merits of Good Friday as the cause for the Easter triumph, failing to adequately recognize the full weight of Jesus’ continued work on Holy Saturday.

In Balthasar’s perspective, any idea of Jesus’ “triumphant” demeanor must not imply that this attitude had anything to do with knowledge or confidence in personal triumph. In the Trinitarian love of God, there is no concern for self; there is only concern for the other. His love was so great, that he was willing to suffer even the torments of hell and separation from the Father, in faith that it was the Father’s will for the salvation of his creation. While he knew that the Father would triumph, his knowledge of triumph was not necessarily foreknowledge that he would ultimately be exalted. His joy was only in doing the will of God, and his hope was that man might be saved through his suffering, even if he himself would not experience that salvation. Balthasar’s thought shows us that Jesus was prepared for unlimited suffering, both in degree and duration. The sacrifice of Jesus was truly a total sacrifice, one that he would have been willing to endure for all eternity if necessary.

A meaningful way to reflect on this question is to ask, “What punishment would we endure without the merits of Jesus?” If our conclusion is “hell,” or “eternal separation from the Father,” then don’t we have to consider that this was what Jesus had to suffer in order to reconcile us with the Father? We use physical analogies to describe the torment of hell, but these are merely representations which ultimately, no matter how painful they may seem, fall short of the true punishment of hell. The true punishment of hell is being fully separated from God, with no hope of reconciliation. In reflecting on this question, grappled with by the Church Fathers, Balthasar wonders “might the fire meant by Christ be a ‘spiritual’ one, consisting of the tortures of conscience in the sinful soul that knows itself to have fallen away from God’s order forever?”12

According to Balthasar,

The penalty which the sin of man brought on was not only the death of the body. It was also a penalty affecting the soul, for sinning was also the soul’s work, and the soul paid the price in being deprived of the vision of God. As yet unexpiated, it followed that all human beings who lived before the coming of Christ, even the holy ancestors, descended into the infernum. And so, in order to assume the entire penalty imposed upon sinners, Christ willed not only to die, but to go down, in his soul, ad infernum.13

In our focus on the Sacrifice of Jesus, we would do well to consider its true Scriptural precedents and its theological implications. Clarifying our beliefs about the reasons for the Cross and its lasting results is essential for the basis of authentic Christian faith. And in striving to receive insights into this mystery, we must not forget the constant corollary to sacrifice. While we may debate and speculate as to the nuances of that mystery, what is not debatable is the imperative of participation. The Exodus Hebrews understood that it was not exclusively the death of the lamb that spared them from death, it was their own participation in that death. By consuming the lamb, the Hebrews consummated their covenant membership. So while the death of the lamb and the sign of the blood on the outside of their homes were necessary, they were not enough to save the Hebrews—only fully receiving the gift of the lamb ensured their salvation. St. Paul reminds us of his obligation, as well as ours, to make up “what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ on behalf of his body” (Col 1:24). What could be lacking in Christ’s sacrifice? Nothing, of course, except our participation.

- Anselm of Canterbury, Cur Deus Homo (Oxford and London: John Henry and James Parker, 1865), 28. ↩

- Ibid, 80. ↩

- Balthasar, Hans Urs Von, Mysterium Paschale (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1970), 13. ↩

- Ibid, 103. ↩

- Chadwick, Henry, trans, Saint Augustine: Confessions (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 220. ↩

- Willis, John R., ed, The teachings of the Church Fathers (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2002), 337. ↩

- Veyne, Paul, The Roman Empire (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987), 59. ↩

- Ibid, 60. ↩

- Ibid, 77. ↩

- Ibid, 79. ↩

- Balthasar, Hans Urs Von, Mysterium Paschale (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1970), 165. ↩

- Balthasar, Hans Urs Von, Dare we hope “that all men be saved”? With a short discourse on hell (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 51. ↩

- Balthasar, Hans Urs Von, Mysterium Paschale (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1970), 164. ↩

A helpful article. My only question is re: your statement that Jesus’ “knowledge of triumph was not necessarily foreknowledge that he would ultimately be exalted. ”

This contradicts Jesus’ prediction that he would rise from the dead after 3 days.

Hello Mr. Gates. The notion of sacrifice is certainly a difficult one. You begin your article saying sacrifice is troublesome and inconvenient, but “The most difficult part of truly understanding sacrifice, in a religious sense, comes from our unwillingness to admit that we owe anything to anyone other than ourselves.” If this is the predominant reason for Catholics today having difficulty with sacrifice, then it seems to me that our problems are deeper than lacking a righteous sense of justice. This sense of sacrifice (required for justice) is necessary certainly for the righteousness of the Old Covenant. In the New Covenant, it seems important to me to say, the intimate linking of sacrifice with love is crucially important. The Son was sent – and His sending included His sacrificial death – because “God so loved the world.” (Jn 3:16) God did more than satisfy law; He acted in love.

It is love, it seems to me, that demands our participation – the participation you rightly point out is required of us in His Cross. We are to “present our bodies a living sacrifice” (Rom 12:1), our “spiritual worship.” In this way we love the Lord our God with a whole heart, mind, soul and strength – and neighbor as self. In this way we live in the communion of His Trinitarian love. In this way we “sacrifice” – we “make holy” – we make a gift of – our lives offered up to Him, in Him and with Him.

The notion of sacrifice is so difficult for us, I think, because love is so difficult for us. Love – divine charity – is free but it is not cheap. It came to us at a price, and it is shared by us at a price. At the beginning of the journey, if the cost seems too high, it can be thought of as an investment! “… for the joy set before Him [He] endured the cross…” (Heb 12:2) Thus more than “our unwillingness to admit that we owe anything to anyone other than ourselves,” I think a main problem is our unwillingness to dare to be loved, and to love in return.