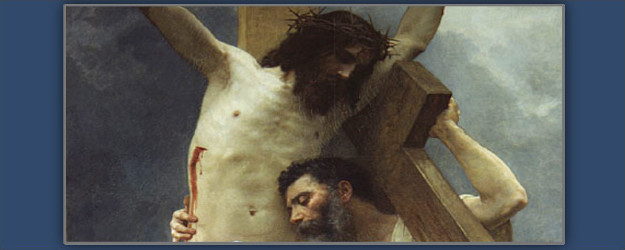

Compassion, by William A. Bouguereau, 1897.

The Advent and Christmas seasons are upon us. Like the reality itself, we Christians have to look more deeply to see the mystery beneath the glitter and the commotion. God has now descended into his creation to take up his rightful place as Lord and King of Heaven and Earth. He has infiltrated enemy lines in this civil war which rages in each of our divided hearts. In the history of this great battle, only one faithful woman has been his totally. Only she has never strayed, only she has never refused a command, only she is wholly his. The rest of us must be won back through an eternal promise of an eternal labor: Christ’s defeat of sin and death and his extending his life and love in all his elect. This is the great story now made visible in a small cave in Bethlehem. At the center of this scene is Mary, the Mother of God, and in this singular act, she has become the Mother of all God’s children.

And here is where one mystery unfolds into another. Mary intercedes and shares her maternity with all the baptized so that we, too, might bring Christ into the world. Gerard Manley Hopkins thus likened each of us to “New Bethlems,” in whom Christ can once again take on flesh:

Of her flesh he took flesh:

He does take fresh and fresh,

Though much the mystery how,

Not flesh but spirit now.

And makes, O marvelous!

New Nazareths in us,

Where she shall yet conceive

Him morning, noon, and eve;

New Bethlems, and he born

There, evening, noon, and morn.

Our Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that there are four primary reasons the Word becomes flesh. The first motive for God’s becoming human is to reconcile us to his and to our Father: “The Word became flesh for us in order to save us by reconciling us with God, who ‘loved us and sent his Son to be the expiation for our sins … the Father has sent his Son as the Savior of the world … to take away sins’” (§457) (boldface mine). Death was the result of our divine disobedience, so God himself had to take on that which could die in order to atone for what we mortals incurred. Our Lady gives the immortal Author of Life what he needs to reconcile sinners to the Father, his mortality. This is a great paradox: Mary’s loving God enough to give him whatever he asked from her, not only to the point of death, but even death itself.

The second reason the Catechism gives is epistemological in nature. It is standard Thomistic philosophy that the human person has in his intellect only that which he first beheld through his senses. Therefore, in teaching that “The Word became flesh so that thus we might know God’s love” (§458), the Church provocatively argues that love is something that we can see, hear, touch, and even taste. For us Christians, love is not a feeling or an emotion. Love is a person, now an incarnate person, Jesus Christ, who has come to teach us how true love is made manifest: through humble obedience to the Father, and to the point of laying down one’s life in whatever way the Father might ask.

Third, at §459 of the Catechism, we learn that “The Word became flesh to be our model of holiness: ‘Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me.’ ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me.’ On the mountain of the Transfiguration, the Father commands: ‘Listen to him!’ Jesus is the model for the Beatitudes and the norm of the new law: ‘Love one another as I have loved you.’ This love implies an effective offering of oneself, after his example.” Holiness has its roots in the same word for our English “wholeness” (as sanctity is related to sane). The divided heart will never be holy because it will never know (or get!) what it wants. “Lord, grant me chastity, but not yet,” prayed the young Augustine. That type of prayer will never bear fruit because the one praying will never be whole. Christ is born to us to show us the ultimate and unifying end of our life: to embrace him, to love him, and in that love, to love all others. Here is our wholeness, and only here can we realize our holiness.

Finally, section §460 is perhaps my favorite passage in the entire Catechism: “The Word became flesh to make us ‘partakers of the divine nature.’ ‘For this is why the Word became man, and the Son of God became the Son of man: so that men and women, by entering into communion with the Word and thus receiving divine adoption, might become children of God.’ ‘For the Son of God became a man so that we might become God.’ ‘The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods.’” Here the Church enlists some of her greatest saints and theologians: Pope Peter, Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius of Alexandria, and Thomas Aquinas. Here is the “second half” of the Christmas story, if you will. Whereas the first half was about God’s descent into the human condition, the second half is about humans appropriating God’s condition—in Christ, to become immortal and wise, loving and merciful, to become filled with the Holy Spirit and to cry out to the very same Father as the eternal coheirs of his only (begotten) Son. The DNA may be different, but we have been made children through grace, and at Bethlehem, we gaze upon the beginning of this adoption process. As God’s children, we are made participants of his nature, now given the power needed to live no longer merely human lives, but to rise above our own fallen instincts and biological impulses to live the life of the Spirit.

Yet, notice how the Church does not allow us much time to bask in the joy of these Christmas graces without reminding us of what precisely this new birth means. The Nativity itself is followed by three days of celebrating those whose lives were ended because of the New Life in the crèche: Stephen, the Apostle John, and the Holy Innocents. When the liturgical year was codified, these three days were purposefully put immediately after the Birth of Our Lord. For when God descends into enemy territory, he calls on his brothers and sisters in arms to join him in warfare against the world’s powers. These three feasts thus celebrate the three ways of martyrdom: Stephen, who dies, both in desire and in deed, offering himself to the brutal hands of his persecutors; John, who dies in desire while in exile on the island of Patmos; and the Holy Innocents, who die unknowingly in deed alone. While Stephen was the first to die a red martyrdom, John was the first white martyr, and the babes of Bethlehem remind us what a cruel world this can be for those even associated unconsciously with Christ. A sleeping child casts down the mighty from their thrones.

As Christians in a hostile land, we need to continue to pray, to glory in Christ’s sacraments—daily, if possible—and to grow always in charity, and to read, read, read. As editor of HPR, I receive dozens of books each month to be reviewed. Fr. Baker, the éminence grise of this journal (who is not slowing down, but just emailed me about translating some lesser-known works of St. Robert Bellarmine, SJ, from Latin into English!), used to carry out this gargantuan task alone. I, however, have needed to rely on a cadre of scholars who receive books appropriate to their discipline. Of the many books that pass across my desk, it seems Scott Hahn’s name appears more than others. Here is a scholar and an evangelist who needs no introduction, but do allow me to conclude, by highly recommending to you his most recent book, Joy to the World: How Christ’s Coming Changed Everything (And Still Does) (Image Catholic Books, 2014; www.ImageCatholicBooks.com). It lists at just over $20 and is filled with enough solid theology to last well past the Christmas season.

Blessed Advent, my friends, and Merry Christ’s Mass, when he comes!

I am really enriched by reading the article “Why God becomes human”. Very often we read Vatican II, Catechism of the Catholic Church, Papal and curial documents but never pay attention to the core elements of the teachings. Really, Fr. David Meconi has brought out beautifully the message of reason for being human. I am thinking in these days why we celebrate Christmas and what should be the real reason to celebrate. by reading this article I am able to cherish the meaning of Christmas. Thank you, Father, for enlightening me with the following on:

1. Reconciling with God

2. Knowing God’s Love

3. Model of Holiness

4. Partakers of the Divine Nature.

Its my first time on this site. Was curious after noticing a thread on my face book. Got to say that I’m enlightened by the article but most importantly feel incredibly inspired. have book marked the page and returning. God Bless all and have a Peaceful, Meaningful and a Holy Christmas.

Thank you for this article, Father. I must admit to being a bit squeamish at the title “Why God becomes human.” In the aftermath of Vatican 2, where two generations of Catholics are either indifferent to, or flat out reject the dogma that Jesus, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity always was and always will be a Divine Person only, and never was and never will be a human person, it is easy to tell how the title could be startling. Though Christ took on a human nature in order to fulfill the Salvific prophecies, when an opportunity to instruct in the dogma of the Hypostatic Union presents itself, one should never hesitate to utilize it. Just my opinion, and as the readers of HPR tend to be much more informed than the average Catholic, this is probably preaching to the choir. A Merry Christmas to all.

Regarding “Why God becomes Human,” I am of the opinion that Jesus incarnated because this was always God’s plan, His desire and intention. I do not believe that without sin the Incarnation was unnecessary. Incarnation was never dictated by any need of man, but by God’s free desire. Redemption and salvation are the result of God’s love. Jesus was not an afterthought that happened because mankind did not keep our part of the covenant with God. Jesus was not Plan B – he was “born of the Father before all ages.” The Incarnation was not a reaction, but an initial action that caused creation in the first place. That is my humble opinion.