St. Benedict Blessing Maurus (1420), by unknown illuminator (Tempera, gold leaf, and ink on parchment).

For most Catholics in the United States, the terms “homily,” “sermon,” and “preaching” nearly exclusively evoke the occasion of a priest or deacon preaching as part of Mass.1 While it may seem, based on the typical experiences of many Catholics in the United States, that preaching is indeed only done during Mass, our Catholic faith is replete—in both teaching and example—with many forms of preaching that exist in addition to the well-known Eucharistic homily.

Throughout the post-Conciliar period, the Church points to the existence of forms of preaching beyond the Eucharistic homily. In Dei Verbum (1965), the “ministry of the word” is sub-categorized into “pastoral preaching, catechetics, and all Christian instruction.”2 The “liturgical homily” is specifically stated as being given the “foremost place,” thus revealing it to be within the realm, yet not equivalent to the whole of, pastoral preaching.3 Pope Paul VI provides more language for these forms in Evangelii Nuntiandi (1976), noting homilies at sacraments, paraliturgies, and generic “assemblies of the faithful” (not specifically Eucharistic celebrations).4 In Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Homily in the Sunday Assembly (1982), Catholic bishops in the United States identify forms of preaching in “evangelistic gatherings,” the catechumenate, Bible studies and prayer groups, youth ministry, spiritual renewal programs, and religious education that differ from the Eucharistic homily, the focus of the document.5 In the Code of Canon Law (1983), we hear of “other forms of preaching adapted to needs” and preaching as part of “spiritual exercises” or “sacred missions.”6

The repeated mentioning of non-Eucharistic forms of preaching (the Church also refers to them as “types” or “kinds”) is not an accident or mere slip of the pen. We are to cultivate, explore, and actually utilize these forms of preaching for the fullest communication of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, realizing, that these additional forms of preaching are not simply optional extras for parish life or only suited for the “really devout.” Why is this so important? The many forms of Catholic preaching are presented by the Church as complementary, and not in competition with each other. The U.S. bishops caution against relying on the Eucharistic homily as an exclusive form of preaching, explaining, “even though the liturgical homily (referring specifically to a Sunday Eucharistic homily) can incorporate instruction and exhortation, it will not be able to carry the whole weight of the Church’s preaching.”7 Catholic preaching is something broader, larger than the Eucharistic homily alone. If the typical person in the pew is only regularly exposed to Eucharistic homilies, something is lost—something is missing—and our Church suffers.

Emphasizing and utilizing the many forms of Catholic preaching forms a necessary complement to Eucharistic preaching, in no way lessening the central importance of the Eucharistic homily intrinsically tied to the sacrifice of the Mass. The Church teaches that within the broader context of preaching, the Eucharistic homily is “preeminent,” holding “pride of place” as the “most important,” since it “occupies a privileged position … (taking) up again the journey of faith put forward by catechesis and bring(ing) it to its natural fulfillment.”8 The Eucharistic homily is “underlined” as a place of “ongoing education in the faith,” after the proclamation of the Gospel and catechesis.9 Pope Paul VI writes that because this form of preaching is “inserted in a unique way into the Eucharistic celebration,” it “receives a special force and vigor … to the extent that it expresses the profound faith of the sacred minister.”10 The Eucharistic homily is the place where those in “the office of priests” “perform the sacred duty of preaching the Gospel, so that the offering of the people can be made acceptable and sanctified by the Holy Spirit.”11 In summary, there is an “intimate link between preaching and the celebration of the sacraments, especially of the Sunday Eucharist.”12

From this we see that Eucharistic preaching is decidedly different, separate as a form from other types of Catholic preaching because of its theological distinctiveness—namely, its function in the ongoing life of faith of the initiated and its complete integration into the dynamic actions of Mass—assembling in response to a call, hearing the Word of God, and responding with praise, adoration, supplication, and sacrifice.13 At the same time, the Eucharistic homily is of a “specific nature”—not equivalent to Catholic preaching as a whole.14

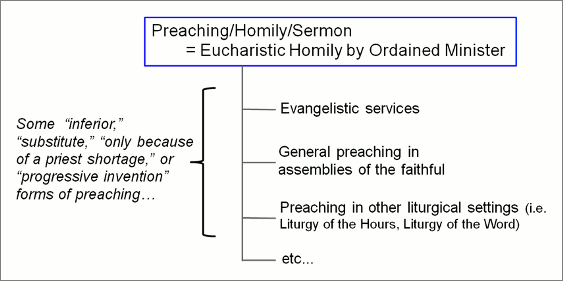

This means that while many Americans might imagine a classification chart of Catholic preaching that looks something like this:

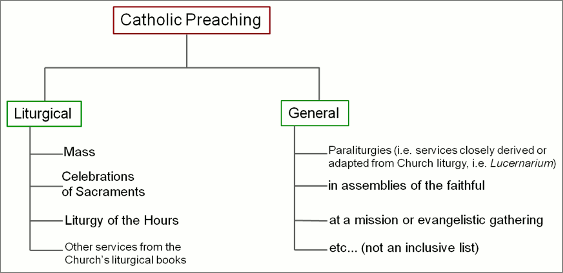

Church writings actually point to a schema of complementarity—where a Eucharistic homily uniquely “enables the gathered congregation to celebrate the (Eucharistic) liturgy with faith,” while complementing all other forms of preaching, “by attending more specifically to what it is to accomplish.”15 This points to an arrangement of forms of Catholic preaching by setting, such as this:

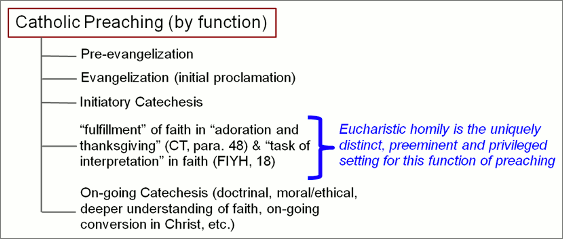

Or, an arrangement of forms of Catholic preaching by function, such as this:

Preaching can, of course, include multiple functions within the same setting, for example, “the same homily … can take on both the functions of convocation and of integral initiation.”16

One might be thinking, “I get it! Catholic preaching is not to be reduced or limited to just Eucharistic homilies. There are many forms of Catholic preaching—but why does this matter?” Here’s why it matters—understanding and utilizing the varied forms of Catholic preaching is critical for allowing each form to fulfill its role most optimally, for the good of the Church and the world. The Eucharistic homily is an integral part of the Mass, its “very meaning and function … is determined by its relation to the liturgical action of which it is a part.”17 Within Mass, “the liturgy of the Word and the Eucharistic liturgy, are so closely connected with each other that they form but one single act of worship.”18 The Eucharistic homily takes “into account both the mystery being celebrated and the particular needs of the listeners” for this act of responding to call and offering worship, adoration, thanksgiving, and sacrifice.19 Thus, to preach a Eucharistic homily at another liturgy (i.e., Liturgy of the Hours) or in the setting of a general assembly of the faithful for the primary purpose of ethical instruction is to betray this specific form of preaching. Likewise, to assert that a homily preached by a layperson in a paraliturgy for the purposes of evangelization should be repeated as a Eucharistic homily because it was “good preaching” is to abandon the distinct role of this specific form of preaching.

Each form of preaching, “in its own way,” “make(s) it possible to familiarize the faithful with the whole of the mysteries of the faith and with the norms of Christian living.”20 Embracing the many forms of Catholic preaching present in Church teaching frees us from the futile task of attempting to hammer a square peg into a round hole when it comes to “proclaiming the word of God in a way that gives birth to and nourishes faith”—the essence of Catholic preaching.21

What is a “Liturgical Theology”?

Although the Church affirms and suggests a variety of forms of preaching based on setting and function, only the liturgical theology of the Eucharistic homily is particularly well developed in post-conciliar teaching and in the guidance of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). This liturgical theology has been fruitful—leading many towards a renewed interest in, understanding of, and dedication to (as both preacher and participating member of the assembly), the Eucharistic homily. Yet before jumping to embrace and utilize preaching in the context of the Liturgy of the Hours as another form of liturgical homily, we must seek to truly understand the liturgical theology that shapes this preaching.

By “liturgical theology,” I do not simply mean the independent study of ritual details, rubrics, or historical examples, but instead the task of naming “the ritualized response by the body of Christ to the activity of the Trinity.”22 Liturgy is not merely a ritual event (though as physical beings, in the words of Jean Corbon, “the liturgy cannot be lived at each moment … unless it is celebrated at certain moments”)—but is more foundationally “the work of Christ on behalf of the vital interests of the clan to which he belongs: the family of Adam and Eve.”23 In short, this means examining what is it about the Liturgy of the Hours as “a place of communion with God” and the Liturgy of the Hours as “a public act for the community in which one dwelled” that helps us understand how, when, and why we preach as a part of (not merely a speech given in the context of) this particular liturgy of the Church.24 This can guide us toward better pastoral practices and applications that support the renewed participation in this liturgy, “not as a beautiful memorial of the past, demanding intact preservation as an object of admiration,” but “rather … as open to constantly new forms of life and growth” as “the unmistakable sign of a community’s vibrant vitality.”25 First, I will set a background context by summarizing how the Liturgy of the Hours is an act of liturgical theology with a complementary relationship to the Mass, and what possibilities this creates for preaching. Then, I examine both the historical practices of Christians and the integrative theology within the Liturgy of the Hours as a departure point for describing preaching suited for this liturgical role.

A Liturgical Theology of the Liturgy of the Hours

The “purpose of the liturgy of the hours is to sanctify the day and the whole range of human activity.”26 This purpose is not accomplished by humanity alone, but by Christ, through the Holy Spirit, present and working “in the gathered community, in the proclamation of God’s word”—making liturgy both “our product and not our work at all.”27 As a liturgical action, it has a cosmic dimension—stretching beyond the present moment, as in the Liturgy of the Hours, the Church “unites itself with that hymn of praise sung throughout all ages in the halls of heaven,” while at the same time receiving “a foretaste of the song of praise in heaven, described by John in the Book of Revelation.”28 The Liturgy of the Hours gives action to “the essence of the Church to be visible yet endowed with invisible resources, eager to act yet intent on contemplation, present in this world yet not at home in it,” reflecting Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s image of liturgy “as a journey of leaving the world for the sake of the world.”29 It is truly a “public service, in which the faithful give themselves over to the ministry of love toward God and neighbor, identifying themselves with the action of Christ, who, by his life and self-offering, sanctified the life of all mankind.”30

How exactly does this happen for the Christian? Augustine describes the individual Christian who, “like an ant, ‘runs daily to the church of God, to pray, to listen to the lesson, to sing the hymn and to ruminate on what he has heard.’”31 In this, we see the “structure of the liturgy” “shap(ing) the lives of liturgists (the baptized);” there is a “ritualized response by the body of Christ to the activity of the Trinity,” experienced particularly in the Liturgy of the Hours through the presence of “God’s revealed word in the life of his community.”32

The Liturgy of the Hours is not simply an optional accessory to the Mass, but “a kind of necessary complement by which the fullness of divine worship contained in the Eucharistic sacrifice would overflow to reach all the hours of daily life.”33 The Liturgy of the Hours:

extends the praise and thanksgiving, the memorial of the mysteries of salvation, the petitions and the foretaste of heavenly glory that are present in the Eucharistic mystery … (it) is, in turn, an excellent preparation for the celebration of the Eucharist itself, for it inspires and deepens in a fitting way the dispositions necessary for the fruitful celebration of the Eucharist: faith, hope, love, devotion, and the spirit of self-denial.34

In this, we see the relationship between training or practice (“asceticism”) and liturgy as a “way of living and a way of thinking … within the fundamental liturgical mysteries of creation, sin, salvation, and deification.”35 In this task of participation in the Trinity, celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours is never in competition or comparison with celebration of the Eucharist, the relationship is complementary. The Mass is

the “source and summit” of the whole liturgical life and the entire Christian life … But if we say summit, the culminating point, then we imply that there are paths up to the summit and down from it which link it with the plain below. If we say source, we imply that there are streams which carry its life and freshness far and wide. This summit and source should not remain isolated: the different Hours ensure a preparation and continuation throughout the whole of our working day. This prevents the Eucharist from becoming an enclave or island which we could come to regard as an escape or alibi.36

The liturgical theology of the Liturgy of the Hours reveals that preaching in this context should be approached as another action of Christ working to bring forth a product (in the act of preaching or listening) in each Christian present. Preaching in the Liturgy of the Hours can support the overarching purpose of sanctifying human activity, shaping each of us to be “eager to act” as leaven in the world, but without abandoning contemplation.37 Since the Liturgy of the Hours offers a particularly focused encounter with the Word of God present in the Scriptures, preaching can facilitate each person’s “rumination” on what he or she has heard.38 Preaching in the context of the Liturgy of the Hours can both prepare us for, and encourage, the continuation of the mysteries encountered in the Eucharist.

Describing an “Office Homily”39

Post-conciliar Church teaching and the USCCB’s Fulfilled in Your Hearing have given us a framework for understanding the essence of the Eucharistic homily. In contrast, the openness in the description of a homily during the Liturgy of the Hours as context for preaching has led us to an exploration of the forms of preaching and liturgical theology operative in the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours. Based on our examination of the liturgical theology of the Liturgy of the Hours, we are now prepared to ask, why would one ever make use of the option to preach during the Liturgy of the Hours? How would an Office homily differ from a Eucharistic homily? What makes an Office homily truly an Office homily, and not just another talk? What roots it in the liturgical celebration? What potential might this form and context of liturgical preaching hold?

Why is preaching appropriate in the Liturgy of the Hours? What is the need for it? The Liturgy of the Hours is “conversation between God and his people,” an “exchange or dialogue … between God and us.”40 Taft identifies this movement in his description of the communal celebration of the hours by St. Arles Caesarius in Gaul, “God first calls us in his revealed word, then we respond with the words his call brings forth from our hearts.41 The preacher’s role in the Liturgy of the Hours is to interpret or explain this conversation, this dialogue—to be, in the language of Fulfilled in Your Hearing, a “mediator of meaning.”42 This is not to say the preacher mediates between God and his people, but that he or she represents both the community and the Lord.43 While all present in the celebration “respond with the words (God’s) call brings forth,” the preacher’s words are made known in proclamation, within the assembly. It is because God converses with us and calls forth a response, that preaching is highly appropriate within the communal celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours and inseparably rooted to this particular liturgical context. Because the Liturgy of the Hours is not merely an ascending of our prayers, but includes a response as part of the conversation and encounter with God, preaching flows from the liturgical celebration itself as a particular manifestation of the relationship between God and his people.

What is the content of an Office homily? Would it just be a Eucharistic homily given in a different place? In accord with all other responses during the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours, the Office homily should be “inspired by” and “steeped in” the spirit of Scripture that is prayed and sung throughout the celebration.44 In the Liturgy of the Hours, texts from the Psalms and Old and New Testament canticles, and readings from the Epistles and Revelation predominate. This offers an opportunity to preach on texts that differ considerably in literary form, setting, and purpose from the Gospel and thematically linked Old Testament readings that are most commonly (and often recommended to be) the focus of Eucharistic homilies. Thus, while maintaining one of the same key elements of a Eucharistic homily, “the word drawn from the Scriptures,” the Office homily can be a distinctly different form, given the different themes, contexts, and literary forms present in the Scriptures of its liturgical context.45

In addition to Scripture, the prayers of the liturgy are also mentioned as forming “a wellspring of the Christian life.”46 These prayers—the doxologies, intercessions, silent/private prayers of those assembled, Psalms as prayer, or even “Psalm-prayers” provided in some texts—could be the basis of an Office homily, since they are inspired by Scripture (even if not actually Scripture). While preaching on liturgical texts and seasons is always an option in Eucharistic homilies, preaching on prayer could be emphasized much more in the setting of the Liturgy of the Hours, since the liturgical celebration itself draws such attention to this specific action of speaking and listening to God. The celebration of the Office of Readings offers an opportunity to preach on “the writings of the saints” offered in the readings, so as to “nurture” the Church’s life.47 The opportunity to make these writings a central focus of a homily is distinct from the context of a Sunday Eucharistic homily, where a dominant focus on a particular passage written by a saint is not appropriate, since the congregation will not have heard the full text proclaimed (as in the Office of Readings).

If the “point” of a Eucharistic homily is to enable the gathered assembly to offer praise, thanksgiving, and ultimately ratify the sacrifice of the Mass, what’s the purpose of an Office homily? While sharing many similar elements, the purposes of Office homilies could potentially be broader than those of a Eucharistic homily. The Eucharistic homily is unique in that it helps to enable a response that is “inseparably joined … to the very offering whereby Christ ratified the New Testament in his blood.”48 While this Eucharistic response includes praise and thanksgiving, it is necessarily rooted in the offering of sacrifice. The ratification of the covenant offered by God through the sacrifice of those called (the assembly) is a constitutive aspect of the Eucharistic liturgy, and the Eucharistic homily should be particularly attentive to this.49 As a liturgical celebration, the Liturgy of the Hours also cultivates and elicits praise of God and thanksgiving—thus an Office homily could be oriented towards this end.50 Laudis Canticum also offers the language of this particular liturgy’s function in helping us “recognize our own voices echoing in Christ, and his voice echoing in us.” While this could be a fine theme for a Eucharistic homily, it seems particularly congruent with, and flowing from, the structure of the Liturgy of the Hours. This relationship with Christ—our voices echoing in his, as we are configured to him and Christ speaking and working through us—could be one option for those seeking a unifying purpose for Office homilies. Another potential, guiding telos of an Office homily could be to deepen the faith of those who participate, “lift(ing) up their minds to God, in order to offer him their worship as intelligent beings and to receive his grace more plentifully.”51

Functions of an Office Homily

As discussed earlier, the Church’s teaching on preaching mentions a variety of different functions of preaching, i.e., pre-evangelization, initial proclamation (evangelization), initiatory catechesis, etc. While the Eucharistic homily can include elements of evangelical, instructional, or catechetical preaching—especially in a broader sense—its essence must remain integrally linked to the action of the Eucharist. The Liturgy of the Hours exists harmoniously with the Mass, a “necessary complement.”52 Yet, the liturgical actions of the Liturgy of the Hours and Mass do reveal differences.

Josef Pieper reminds us that in the early Church, “barriers…excluded those who did not ‘belong’ from participating in the sacred mysteries (of the Mass), even those who prepared for baptism, the catechumens.”53 Although as a pastoral practice this is, “for us latter-day Christians, used as we are to taking the television broadcast of Mass for granted … difficult to comprehend,” the reality remains that Mass is not the most suitable liturgical act for the unbaptized. While completely different from the situation of the unbaptized, many pastoral leaders in the United States note the incongruity in wanting to invite those not in full communion with the Catholic Church and/or those unable to receive the Eucharist to offer praise and thanksgiving to God, yet having no liturgical celebration to invite them to, other than the Mass—no setting for them to hear the Word of God explained and interpreted, other than Mass. The Liturgy of the Hours possesses an openness that allows many different functions of preaching to take priority and precedence—it is highly adaptable to the needs and situation of the assembly. Embracing the Office homily as preaching that could, at different times, incorporate different functions of Catholic preaching, safeguards the Eucharistic homily’s “privileged position” of bringing the faith nourished by catechesis to “its natural fulfillment” in ratification of the Eucharistic sacrifice.54

What functions could the Office homily carry? Again, the Church offers an open door, noting that:

people of different callings and circumstances, with their individual needs, were kept in mind and a variety of ways of celebrating the office has been provided, by means of which the prayer can be adapted to suit the way of life and vocation of different groups dedicated to the Liturgy of the Hours.55

Since the “method and form of the celebration” is to be chosen, based on “which most helps the persons taking part,” the same can be said for the choice in function of preaching at the Liturgy of the Hours.56 For example, in Milan, Ambrose used “popular hymns (in vigils) as a weapon against the Arians”—analogously, an Office homily could be used to specifically prepare the faithful in apologetics of evangelization in a particular cultural context today.57 In fifth-century Gaul, communal celebrations of Vigil services “were not only religious celebrations, but also occasions of holiday leisure and good fellowship, of fairs, and going out with friends,” reminding us of the potential function of Office homilies within a broader outreach or parish fellowship effort.58 In Origen’s time, preaching at the Liturgy of the Hours was, on a regular basis, specifically directed to the unbaptized, and often included long readings “equivalent to two or even three chapters in our Bibles,” revealing the potential for preaching to diverse audiences.59

Catholic preaching, as a collective whole, should encompass a wide range of preaching functions. The Office homily is a highly adaptable form of preaching, much less specific than the Eucharistic homily, and thus, able to incorporate the many functions of preaching that the Eucharistic homily cannot, and should not, be forced to “carry.”60 In Fulfilled in Your Hearing, the U.S. bishops warn that the Eucharistic homily simply “will not be able to carry the whole weight of the Church’s preaching.”61 The Office homily too, cannot carry the entire weight of the Church’s teaching—we can, however, utilize this distinct liturgical form of preaching by embracing the content, forms, contexts, and functions most appropriate to particular celebrations of the Liturgy of the Hours. In doing this, the Office homily does not become impoverished, experienced as “a Eucharistic homily not given at Mass,” but instead grows in richness, nourished by the liturgical theology in action, operative in the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours.

Closing

Many in ministry may read this and think, “that liturgical theology stuff is nice—but our calendar is full, and it’s hard enough to get people to Mass these days.” Roguet poses a challenging question to us, remarking:

one may reasonably ask whether Christians who never practice divine praise for its own sake, and who do not come to the church except when listening to the word of God and singing psalms as primarily a prelude to communion, have a true idea of what the Eucharist is.62

The Mass has never been the only liturgical celebration of the Church, nor has the Catholic Church understood preaching to be fully encompassed or accomplished by the Eucharistic homily alone. What is it we should do with the marvelous gift of opportunity to preach in the context of the Church at prayer with Christ in the Liturgy of the Hours? The door stands wide open, as the liturgical action invites us in.

- The use of the specific terms, “homily,” “sermon,” and “preaching” in the Catholic Church seems to flow from a historical, cultural, and/or linguistic context, rather than from a theological or legal context where the specificity in the term implies a certain definition. A merely semantic debate regarding which term to use does not, in my opinion, contribute decisively to developing a liturgical theology of preaching in the Liturgy of the Hours. Awareness of these terms is useful when encountering them in sources. Throughout Church history, the terms homilia, exhortiatio, admonitio, tractactus, and sermo were all used, with sermo beginning to predominate in the fourth century, and outnumbering all other terms by the 12th century. In the 20th century, we see a transition in terms, as Pope Pius XII uses both “homily” and “sermon” in his encyclical on the sacred liturgy, while the Second Vatican Council uses “sermon” in the context of issuing norms, but prefers “homily” throughout the other sections of Sacrosanctum Concilium. Of note, none of the modern source documents for a definition of homily, such as the General Instruction of the Roman Missal or Sacrosanctum Concilium define homily “in terms of who preaches it (New Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, (NY: Paulist Press, 2000), 929-30). ↩

- DV (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation) 24. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pope Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi (Evangelization in the Modern World) (EN), 8 Dec 1975, para. 43. To my knowledge, “paraliturgy” is not formally defined by the Church, though it does appear in Church documents. The term is generally applied to rites and celebrations that use a quasi-liturgical format, i.e., a liturgical format resembling, but not appearing in an official liturgical book (“Follow-up: On Paraliturgies,” Zenit Daily Dispatch (16 Dec 2008), online). ↩

- USCCB, Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Homily in the Sunday Assembly, (Washington, D.C.: Office of Pub. Services, United States Catholic Conference, 1982), p. 2, 27. ↩

- Code of Canon Law (1983) (CIC1983), Can. 770. ↩

- Fulfilled in Your Hearing (FIYH), 26. ↩

- CIC1983, para. 767§1; Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), para. 132; Congregation for the Clergy, General Directory for Catechesis, (1997), para. 51, 70. ↩

- General Directory for Catechesis (GDC), para. 57. ↩

- EN, para. 43. ↩

- Pope Paul VI, Presbyterorum Ordinis (Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests), 7 Dec 1965, para. 2. ↩

- FIYH, 1. ↩

- Louis Bouyer, Liturgical Piety, (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955), 24-25, 29. ↩

- Pope John Paul II, Catechesi Tradendae (CT), 16 Oct 1979, para. 48. ↩

- FIYH, 27. ↩

- GDC, para. 52. ↩

- FIYH, 17. ↩

- Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), para. 56. ↩

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal (2011), para. 65. ↩

- CT, para. 48. ↩

- John Burke and Thomas P. Doyle, The Homilist’s Guide to Scripture, Theology, and Canon Law, (New York: Pueblo Pub. Co, 1987), 43. ↩

- David W. Fagerberg, Theologia Prima: What Is Liturgical Theology? (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2004), 7. ↩

- Fagerberg, 15, 11. ↩

- Ibid., 4, 11. ↩

- General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours (GILH), para. 273. ↩

- GILH, para. 10. ↩

- GILH, para. 13, Fagerberg, 14. ↩

- GILH, para. 16. ↩

- GILH, para. 18, Fagerberg 16. ↩

- Pope Paul VI, Laudis Canticum (Apostolic Constitution on the Liturgy of the Hours), 1 November 1970. ↩

- Dominic F. Scotto, The Liturgy of the Hours: Its History and Its Importance as the Communal Prayer of the Church after the Liturgical Reform of Vatican II, (Petersham, MA: St. Bede’s Publications, 1987), 30. ↩

- Fagerberg, 7; Robert F. Taft, The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West: The Origins of the Divine Office and Its Meaning for Today, (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1986), 180. ↩

- Laudis Canticum. ↩

- GILH, para. 12. ↩

- Fagerberg, 22. ↩

- A.-M. Roguet, Peter Coughlan, and Peter Purdue. The Liturgy of the Hours; The General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Abbey Press, 1971), 140. ↩

- GILH, para. 18. ↩

- Scotto, 30. ↩

- For lack of a less verbally cumbersome way to make “Liturgy of the Hours” into an adjective, I will use the term “Office homily” to refer to preaching during the Liturgy of the Hours. ↩

- GILH, para. 33, 14. ↩

- Taft, 181. ↩

- FIYH, 7. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- GILH, para. 14. ↩

- FIYH, 3. ↩

- GILH, para. 18. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Presbyterorum Ordinis, para. 5. ↩

- Bouyer, 23-29. ↩

- Laudis Canticum. ↩

- GILH, para. 14. ↩

- Laudis Canticum. ↩

- Josef Pieper, In Search of the Sacred, tr. Lothar Krauth, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 34. ↩

- GDC, para. 57; CT, para. 48. ↩

- Laudis Canticum. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Taft, 175. ↩

- Ibid., 183. ↩

- David G. Hunter, Preaching in the Patristic Age: Studies in Honor of Walter J. Burghardt, S.J. (NY: Paulist Press, 1989), 41. ↩

- FIYH, 26. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Roguet, 77. ↩

Thank you for such a wonderful article on a little known subject.

One of the possibilities I thought of in this form of homily would be to embellish a section of that days’ Psalm or reading, inviting people to grow in awe of God and prayer, and just leave it at that.

Question: if a parish had a group Liturgy of the Hours on a regular basis in their chapel, and occasionally the priest and/or sister would be absent, would it be possible for a designated lay person to do the homily? Of couse if it is, the person designated would have to be carefully chosen; also he or she would not attempt to do something above their ability or knowledge.

Perhaps the first step here would be to get more parishes to recite the Divine Office in the first place. I’ve found personally the the Divine a Office is incredibly enriching and helps immerse me in the spirit of the liturgical season or feast day.

I’m all for making the Divine Office something more common at the parish level. People ought to know and utilize this treasure. It would be beautiful to see most parishes at least have Solemn Vespers a few times a week. Once that gets started we can discuss sermons during the Office.

Here where I’m from there is a parish that is quite robust spiritually and I’m convinced it’s because the priests use the Mass Propers instead of replacing them with tacky hymns, confession is offered every day and the Liturgy of the Hours is prayed in the Church in the morning, the afternoon,the evening and right before locking up for the night. Many people actually come to the LOTH too.

I would LOVE to see more parishes taking seriously the Office.