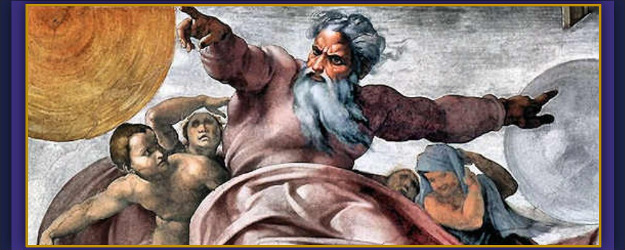

Creation of the Sun and Moon, Michelangelo (1511), Sistine Chapel.

At the heart of Benedict XVI’s papacy, and of the theological and ecclesiastical career of Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, is a highly developed—and in some ways radical—biblical theology. Indeed, all things most characteristic about the work of Ratzinger/Benedict— liturgical renewal, the return to the Church Fathers, the fundamentally catechetical nature of his encyclicals—spring from his Scripture scholarship. This is unique for a pope, and indeed, Scott Hahn goes so far as to say, “Never before in the history of the Catholic Church has a world-class biblical theologian been elevated to the papacy.”1

This biblical theology developed in a time of flux in the Church, not just with the Council, but with the ressourcement and the ongoing revolution in Scripture study. His life has coincided with a time of radical upheaval in many areas of theology, but most notably in the area of exegesis, and in particular in the development of—and the Church’s reaction to—the historical-critical method.

Under Cardinal Ratzinger’s direction, the Pontifical Biblical Commission issued several key Church documents about biblical interpretation, among them, “The Jewish People and Their Sacred Scripture in the Bible” (2001) and “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church” (1994). These documents show Ratzinger’s efforts to refine biblical theology for a new generation by outlining the “hidden dangers” and “positive possibilities” of the various techniques of study. His pointed critique of modern scholarship is a common theme of his writing, as he tries to tease the wheat from the chaff.

The most expansive example of his exegetical technique is found in his magnum opus, the Jesus of Nazareth series.2 An earlier text, however, provides a fascinating glimpse of Ratzinger’s method at work on the vexed subject of Creation. In 1981, he delivered a series of homilies on the opening passages of Genesis—subsequently published as “In the Beginning…”: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall—which sought to reconcile a reasonable understanding of creation and the fall with what the natural sciences now tell us about the universe, the Earth, and the rise of life.

These passages of Genesis are fraught with challenges for the modern Catholic exegete, who must navigate a path between materialism and fundamentalism, which both insist on an overly literal interpretation that is unsupported by the text. By using the tools offered by the historical-critical method, drawing on the Fathers, and practicing canonical criticism (which views each piece of Scripture in light of the whole), he comes to a satisfying solution to the “problems” of Genesis that preserves the deep theological relevance of these beloved passages.

New Methods in the Study of Scripture

In Pilgrim Fellowship of Faith, Joseph Ratzinger recalls his student days, when the consensus was that the historical-critical method had offered the “last word” on the meaning of Scripture. One professor even declined to supervise any more dissertation work on the New Testament, saying that “everything in the New Testament had already been researched.”3 One is reminded of the (possibly apocryphal) story of the Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office who is supposed to have remarked, in 1899, that the office should be closed because “everything that can be invented has been invented.”

The development of new methods began in the early 19th century, when scholars broke from using the textus recepticus4 and returned to Greek and Hebrew texts closer to the sources. The presence of overlapping, variant texts (doublets) in the Pentateuch gave rise to the “documentary hypothesis,” which questioned the tradition of Moses as its sole author, and continued with speculation on the composition of the Synoptic Gospels.

The problem with this approach is that “it did not pay sufficient attention to the final form of the biblical text and to the message which it conveyed in the state in which it actually exists.”5 In a kind of a reverse gestalt, the pieces were judged greater than the whole.

Textual, literary, form, and redaction criticism developed in stages, each contributing something to the historical-critical method that allows us to study community, composition, form, and editing more closely. It is “historical” because it attempts to understand the historic context of the texts and the long process by which they came to their current form. It is “critical” because it attempts to use objective, scientific criteria to analyze a biblical text as one would any other historical or literary document. It seeks the earliest, best manuscripts and subjects them to close linguistic analysis to determine what can be known about the people who produced the text, and the process of writing and revising them.

At first, the new process and the old frequently found themselves in conflict. In time, traditional exegesis came to accept some of the claims about the texts, acknowledging that they were, in fact, produced over time by diverse hands.

Too often, however, the process is separated from the proper placement of Scripture in the Church, with exegetes forgetting that “the text in its final stage, rather than in its earlier editions … is the expression of the word of God.”6 (emphasis added) As Pope Benedict observes, this unity is, itself, a “theological datum.”7

Problems with the Method

The problem with the scientific method of modern biblical criticism is that it developed largely devoid of self-reflection that might have illuminated its limitations. The post-Enlightenment bias of the architects and subsequent practitioners of the historical-critical method inherited “philosophical, epistemological, and historical assumptions”8 as part of the package. They created a method to critique the Bible, but did not linger on a critique of the method itself, and its inherent flaws. They mistook this method—a mere tool, and an incomplete one at that—for a purely rational device by which one could truly understand the source, audience, and meaning of every biblical text.

Yet bias was baked right in the cake. Miracle stories were out. The supernatural was set aside or explained away. Any evidence of subtle and complex theology was seen as proof of late authorship, working under the assumption of another post-Enlightenment bias: the application of the theory of evolution to all things.

Benedict observes that this assumption of the relevance of evolution remains one of the key biases modernist scholars bring to the table, and one which is of particular relevance in discussing creation accounts. They assume a “neo-evolutionary model of natural development” where texts are concerned, asserting that complex forms of a text evolve from simpler forms. If a text is theologically sophisticated, it is late. If it is simple, it is early. These simpler forms must, of course, be closer to the real source, and thus a more “authentic” representation of history.

This process is particularly vexing for Ratzinger when applied to the New Testament, since often it results in trying to tease out the “Hellenistic” from the “Jewish” tradition in Scripture under the assumption that the Greek was a corrupting influence, rather than “an event of decisive importance, not only from the standpoint of the history of religions, but also from that of world history.”9 In other words, the Hellenistic encounter with Christianity was not incidental, but integral, and any attempt to dehellenize any text written in Greek is bound to fail.

Uncertainty

Ratzinger refers often to the “method and limits of historical knowledge,”10 applying Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle11 to his assessment of modern scientific biblical criticism. If the historical-critical method is going to take the natural sciences as its model, it has to also accept its limitations. If the idea of uncertainty is true in quantum mechanics, it’s doubly so in historical research. After all, in the physical sciences, the facts and theories in question must be subject to contemporary testing. A phenomenon must be observed and measured, and the results must be reproducible. Since history has already happened, this is, of course, impossible.

The scholar can never produce a wholly objective model of history or textual interpretation, because he is shaped by countless factors affecting his conclusions. His choice of subject matter, training, knowledge, area of expertise, starting point, intellect, skill, school of thought, epistemology, bias, and even his biography render him a less-than-impartial observer.

Furthermore, since the events of Scripture are the work of humans, the subjective influence of the observer is even greater. Thus we see that the “objective” historian or textual critic is an illusion: objectivity may never be achieved because even the most thorough and “scientific” method—which the historical-critical method certainly claims to be—is subject to all these inherent flaws.

Some practitioners certainly are aware of these limitations, but far more are reluctant to accept them. The history of the method itself belies its own claims to be a “scientific” process. Were it truly a scientific method, truth would have gone from disputed to undisputed, from general to specific, from unknown to known. Progression of knowledge is one of the key elements in the scientific method.

Yet when we look at two centuries of “scientific” approaches to biblical study, we see nothing of the sort. What Ratzinger observed in his lifetime of studying this material was simply this: we do not have one linear progression from imprecision to precision, but, rather, a “history of subjective constellations, whose trajectories correspond precisely to the developments of intellectual history and reflect them in the form of interpretations of the text.”12 In brief, each new generation offers new interpretations that reflect the fads and preoccupations of that generation.

The missing element—the central fatal flaw—of the method is its unwillingness to realize that “faith is itself a way of knowing.” When faith is set aside, the result is not scientific objectivity, but the elimination of crucial perspective on the text under examination. It “refuses to acknowledge the contingency of the conditions of the vision it, itself, has opted for. By contrast, when we realize that the Holy Scriptures come from a subject that is still very much alive—the pilgrim People of God—it is clear, even rationally, that this subject has something to contribute to the understanding of this book.”13

Ratzinger suggests, as a response to this methodological limitation, a “diachronic reading,” which takes the product of each writer and understands it in the context of that writer’s “philosophical presuppositions.” In other words, use the tools of scientific criticism as far as they take you, but don’t labor under the delusion that these tools preserve you from bias and subjectivity. He concludes by urging that this not lead to “skepticism,” but to a self-limitation and purification of the method.

Canonical Criticism: Understanding the Whole

The Fathers were quite correct in understanding the four senses of Scripture, and they also knew that these senses were not “individual meanings arrayed side by side, but dimensions of the one word that reaches beyond the moment.” They held a deeper meaning, and we would not still be reading these texts and drawing out new meanings “unless the words themselves were already open to it from within.”14

Canonical criticism takes on a central role in any attempt to read the Bible with the mind of the Church. The authors are not merely individuals writing for their own benefit, but

part of a collective subject, the “People of God,” from within whose heart and to whom they speak. Hence, this subject is actually the deeper “author” of the Scriptures. And yet likewise, this people does not exist alone; rather, it knows that it is led, and spoken to, by God himself, who—through men and their humanity—is, at the deepest level, the one speaking.15

In the absence of this understanding, the historical-critical method has trouble reaching solid theological conclusions. The Bible as a whole, representing a received text of particular meaning to a particular community, is not just important, but central to a proper understanding of the meaning of Scripture. Canonical criticism—whether it examines the process of canonical development by which a community refines and accepts a text, or the final text itself—attempts to understand the Bible as a “norm of faith” by the community that both produced and inherited it, with each part contributing to “the single plan of God.” Understood this way, it does not challenge the historical-critical method: it purifies and “completes” it.16

Genesis: An Example of Canonical Criticism

Ratzinger was prompted to deliver his homilies on the creation accounts of Genesis after noting the utter of absence of the creation theme from catechesis. It was no longer a tenable concept in the wake of Darwin, and notions of “creation” at the hand of a Creator were being seen as less intellectually honest than ideas like selection and mutation. It was, in fact, dismissed as an “unreal concept.”17

This reductionist approach, however, holds grave implications for the faith, stripping God from any role in the formation of the material world. Yet how do we reconcile the text of the creation and fall—written, as the catechism notes, in “figurative language”18—with what science reveals about the age of the earth and the development of life thereon?

Ratzinger, in citing the opening passages of Genesis, asks the pertinent question: the words are beautiful, but are they also true? Has science—which now measures the lifespan of the universe and the earth in billions of years, and suggests that the rise of life happened gradually—made this nothing more than a poetic fairytale, to be disposed of by modern rational man? Do they merely come out of an “infant age” of mankind which we have left far behind?

Form and Content

Ratzinger’s first layer of interpretation of Genesis is a common one: form versus content. The Bible is not a textbook, and does not attempt to offer modern scientific answers to important questions. In a time when the pendulum has swung so far, that scientific answers are adjudged to be the only relevant answers, this would seem to render the Genesis accounts little more than fables.

That is not, however, what we should take away from a proper understanding of form. The distinction must be made between “the form of the portrayal and the content that is portrayed.”19 The form is determined by the community which wrote the passages, drawn from the images that held meaning for them.

The intent was not to show, for example, how the amphibian came to have its legs, but to show that the world was not created from a swirling chaos or by gods or other mythological creatures, but by one God, the Prime Mover, who, in his Reason and through his Word, wielded the power of creation. It was, in a sense, a counter-narrative, shifting the focus from gods and goddesses, spirits and demons, to the One True God. What’s more, as the Scripture will reveal, God is knowable, and has chosen the Israelites as people uniquely beloved.

Ratzinger offers this answer, but it does not wholly satisfy him for a reason that is central to our understanding of his exegetical method. If this is, in fact, the correct way of reading the creation accounts:

Why wasn’t that said earlier? … The suspicion grows that ultimately perhaps this way of viewing things is only a trick of the church and of theologians who have run out of solutions but do not want to admit it, and now they are looking for something to hide behind. And on the whole, the impression is given that the history of Christianity in the last four hundred years has been a constant rearguard action, as the assertions of the faith and of theology have been dismantled, piece by piece.20

There is a fear that, if the process continues long enough, theologians will run out of places to hide. We’ll be left clinging to a favored text that is no longer reliable.

Furthermore, if the Church can change the way she understands one element of Scripture—seeming to redefine the boundaries between image and intention at will—why can’t she do it for others? If one act of God (creation) is now seen to be merely figurative, based on the revelations of science, why can’t another act of God (the resurrection) be treated similarly?

The Canonical Understanding

In order to come to grips with the situation, Ratzinger refines his question of image versus intention by applying canonical criticism to it, asking if the entirety of the Bible itself makes the distinction, and if the Fathers and the Church recognize that distinction.

His conclusion is that the creation account was never “closed in on itself.”21 From the very beginning of the Israelite encounter with God, the story is about a people struggling to “seize hold of God over the course of time,”22 and of God to make himself known to them. The creation account is not just set down once, as is now clear from careful analysis of the text. It is, rather, something the People of God struggle with and return to over time, perhaps even centuries.

The formation of Scripture was not just a one-time event, but a process of gradual understanding. The only way to truly grasp the ultimate meaning of any passage is not to isolate it, chloroform it, and pin it to a board like a butterfly. It is to follow the living text all the way from the beginning to the end.

That end does not happen when Genesis moves from Creation to the account of the Fall and beyond. It reappears, in a new and more perfect form—when St. John pens the opening lines of his Gospel: “In the beginning was the Word.”

And only then can we understand what Genesis is telling us. As Ratzinger puts it: “every individual part (of Scripture) derives its meaning from the whole, and the whole derives its meaning from the end—from Christ.”23

Genesis is only a partial story of creation. The complete story of creation can only be understood after the Incarnation.

Creation and the People of God

Creation was not a preoccupation of the Israelites until after the Babylonian captivity, when they began looking back at their origins and—drawing on ancient tradition—developed the passages into the form we now know. What they tell the Jews is simply this: God was never just the God of one piece of land or one place. If he was, then he could be overthrown by another, stronger “god.” After Israel lost everything, and began encountering God again in their misery, they came to understand that this was the God of all people, all lands, and indeed, of all the universe. He had this power, first in Israel, then in Babylon, because he created the world and all that was in it.

In captivity, they heard creation myths such as that of the Babylonian Enuma Elish, which tells of Marduk splitting the body of a dragon in two to form the world, and fashioning humans out of dragon blood. All of this dark and primordial nonsense is banished by the image of an earth “without form and void.” No more dragons, no more gods, no more violence and blood: just the pure power of creation from nothing, by a God who made man, not to suffer and struggle and die, but to walk in paradise.

There was order to creation, not chaos. It emerged from Reason, not madness. And it was spoken into being by the Word of God. Indeed, Jews believed that the Torah existed before creation. Creation happened to make the Torah known.

Furthermore, the shape of the creation account itself was meant to echo the Torah and to sanctify time and the week. Time becomes sacred in this account, with man laboring for six days in imitation of God, and resting to worship God on the seventh, in imitation of the “rest” of God Himself. The creation accounts thus build towards, and culminate in, the Sabbath, “which is the sign of the covenant between God and humankind.”24 In a very real sense, then, the creation account can be seen as liturgical: “Creation exists for the sake of worship.”25 That final day is a day in which humanity itself participates in the freedom of the almighty, provided to us in the covenant. We “enter his rest” (in the words of Psalm 95 and Hebrews).

Continuing Creation

Creation accounts don’t end with the first paragraphs of Genesis. There’s another one right away in Genesis, and then more in the Psalms and the Wisdom literature. The Wisdom literature—written under the Hellenistic influence—then forms a bridge to the New Testament, which recasts creation in Christological terms in the opening lines of the Gospel of John. We understand, at last, that “In the beginning,” the logos and the spirit—the intellect and the will—of God, were with God, and that the world bears the imprint of the divine thought. We see the theme of creation not as a one-time closed moment depicting a literal event in a literal way, but as a recurring motif of birth and renewal flowing through the entire text of the Bible.

These accounts use different images because they emerge from different milieu and are speaking to a different audience. Do we really think the redactors of the Scripture were unaware that two accounts of creation and the formation of man were placed back to back in the text? Of course not: they included them because each used images which spoke to the People of God in unique ways and recalled particular times and places in which they were written. It is, in fact, these so-called “contradictions” that tell us most truly that we are dealing with images that are malleable, adapted to speak to the community’s needs.

By isolating each book, each text, and each piece of text, the historical-critical method becomes incapable of conducting a proper analysis of these passages. The techniques can reveal certain things about structure, language, and even community, but they will always fail to grasp the true importance of a biblical text for a very simple reason: they’ve ruled out the theological meaning of a theological text. They’ve put aside the very idea that the passages tell a certain truth in a specific way.

Furthermore, the relevance of the natural sciences to these texts is non-existent. They can neither confirm nor deny, prove nor disprove, the words of Genesis. It’s like claiming a botanical thesis can somehow illuminate the true meaning of Shakespeare’s words about the rose. It does not tell us literally “how” God made the universe and all that’s in it. It tells us that he made it, and that he was a God of love and reason, and that, therefore, the world is derived from his infinite Reason, and may thus also be considered reasonable.26

And if creation is reasonable, then faith, too, is reasonable.

Bibliography

Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: United States Catholic Conference, 2000).

Hahn, Scott. Covenant and Communion: The Biblical Theology of Pope Benedict XVI. (Great Britain: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2009).

Pontifical Biblical Commission. “Interpretation of the Bible in the Church.” (ewtn.com/library/curia/pbcinter.htm).

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal. “Exegesis and the Magisterium of the Church.” ed. José Granados, Carlos Granados, and Luis Sánchez-Navarro, trans. Adrian Walker. Opening up the Scriptures: Joseph Ratzinger and the Foundations of Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008).

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal. In the Beginning…’: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall. (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995).

(Ratzinger) Pope Benedict XVI. Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration. (New York, Doubleday Religious Publishing Group, 2005.

Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal. Pilgrim Fellowship of Faith. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005).

- Scott Hahn, Covenant and Communion: The Biblical Theology of Pope Benedict XVI (Great Britain: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2009), 13. ↩

- Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration (2008), Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to The Resurrection (2011), Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives (2012). ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Pilgrim Fellowship of Faith, (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2005), 27. ↩

- A succession of Greek texts compiled from several manuscripts by Erasmus and others. ↩

- Ratzinger, Pilgrim. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration (New York, Doubleday Religious Publishing Group, 2005), Kindle Locations 231-235. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, “Exegesis and the Magisterium of the Church,” ed. José Granados, Carlos Granados, and Luis Sánchez-Navarro, trans. Adrian Walker, Opening up the Scriptures: Joseph Ratzinger and the Foundations of Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008), 135. ↩

- Werner Heisenberg (1901 to 1976) was a German theoretical physicist who observed that the more precisely one property of a particle is measured (say, its momentum), the less precisely another property can be measured (such as position). Put simply: there are limits to how much we can know about an object in question because when we achieve precision in one area, we surrender it in another. ↩

- Ratzinger, “Exegesis,” ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Benedict, Jesus, Kindle Locations 250-251. ↩

- Ibid, Kindle Locations 258-262. ↩

- Pontifical Biblical Commission, “Interpretation of the Bible in the Church.” (ewtn.com/library/curia/pbcinter.htm). ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, In the Beginning…’: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, (Grand Rapids, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995), xi. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church: Second Edition (Washington, DC: United States Catholic Conference, 2000), 300. ↩

- Ibid, 5. ↩

- Ibid, 6. ↩

- Ibid, 8. ↩

- Ibid, 9. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid, 27. ↩

- Ibid, 28. ↩

- Einstein wrote that the laws of nature “revealed such a superior Reason that everything significant which has arisen out of human thought and arrangement is, in comparison with it, the merest empty reflection.” ↩

Mr. McDonald this paper is excellent I cannot comment on it since it is what I studied for 4 years in Scripture classes with the Vincentians, Jesuits and U of Dallas obtaining a licentiate in theology and scripture. I have used and have commentaries of Father Bruce Vawter, CM God bless you.

I am enlightened by this article’s explanation of canonical criticism, a furthering of the canonical exegesis that Ratzinger touches on in the foreward to Jesus of Nazareth. The contrasting of this method with the historical critical method provides one an understanding of the shortcomings of the latter and the logic behind, and the completeness of, interpreting the scripture holistically. Preserving the theological meaning for the authoring community is afforded by canonical criticism, whereas the historical critical method tends to sanitize the text of any such meaning. Thank you for the education.

Excellent. The historical-critical method bears somewhat the same relationship to scripture that deconstruction does to, say, a play by Shakespeare. It might yield some useful insights and reveal things that might otherwise be overlooked. But in the end, the play has to be seen whole, as a work of art, a vision of reality. It is only by surrendering to the work as a whole that one can begin to grasp it’s “meaning.” Likewise, it is the entirety of scripture, experienced through faith, that has meaning.

Thomas,

Read section 42 of Verbum Domini by Pope Benedict. In it he is saying that the massacres of the Old Testament were sins not commands of God. If they are, the whole 12th chapter of

Wisdom should be removed from the canon because it says God ordered the Canaanite massacre…. as does many other scattered passages as late as Isaiah. Check and ruminate whether or not he himself errs in saying that such passages must be studied by those trained in historical-literary criticism. Literary won’t help with 70 AD which is very modern and historically recounted by Josephus and

Tacitus….and predicted by Christ as punishment for Jerusalem not knowing the day of its visitation. I think he fell victim to human respect and being embarassed at the violence of the OT. St. John Paul II likewise shows embarassement in section 40 of Evangelium Vitae at the God mandated death penalties of Deuteronomy. Check both texts…VD sect.42 and EV sect.40.