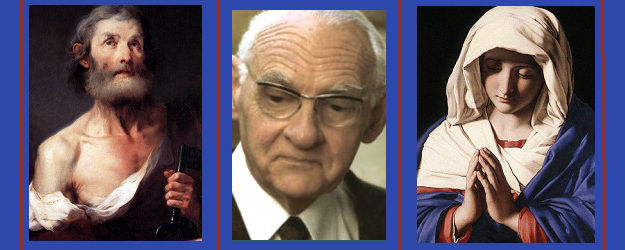

St. Peter the Apostle, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and the Blessed Virgin Mary in Prayer by Sassoferrato, 17th century

Hans Urs von Balthasar has proposed that a dialectic, or “reciprocal relationship,” exists between the objective and subjective holiness of the Church—represented by the persons of Peter and Mary—which he associates with its institutional and spiritual aspects, respectively.1 While the Church distinguishes between the two, it also continuously teaches that the Church is one, thus leaving to the theologian, or theologically curious, the task of resolving this Mystery. In the following pages, I will present von Balthasar’s dialectic, from its foundation in the person to its implications for ecclesiology, and reference the dogmatic constitution of the Church, Lumen gentium, to highlight how the Church understands its Petrine and Marian aspects. This will include a treatment of how the Belgian biblical scholar, Ignace de la Potterie, contributes to our understanding of the economy of this dialectic. Finally, I will conclude with a reflection on how von Balthasar’s dialectic provides theological context for the pastoral concerns of the contemporary Church.

In developing his dialectic between the Petrine and Marian aspects of the Church, von Balthasar grounds his approach in anthropology, and the economy of human relationships. He describes the interior life of the individual as a wholly subjective experience, i.e., exclusive to the subject, protected from the grasp of the other, but also limited by the very fact of its interiority, and suggests that only in an act of self-expression can the individual experience freedom.2 In this act of self-expression, two things occur. First, the subjective experience is transformed into an objective expression, taking the otherwise personal experience and birthing it for the experience of the other.3 In an analogous sense, the objectified experience is a child of the individual, independent of, yet still associated with him and, for this reason, the individual can exercise “parental” caution with his expressions, “the mentality of the private individual,” from which sin grows.4 Second, the individual becomes aware of the freedom of expression as something in its own right which motivates him to seek out other opportunities for sharing. However, this sharing presupposes that the individual knows what it means to understand another. As von Balthasar explains, “it could never hold to such a hope if it had not itself already had the experience of what it means to perceive, understand, and receive a personal and free word in itself.”5 The individual must first be in a state of having learned what it means to perceive the other, which von Balthasar has characterized as feminine, before he can then surrender himself to the perception of the other, which he has characterized as masculine.6

Though von Balthasar states that the person is “intrinsically ordered” to be relational, he also emphasizes a maternal influence in constituting the person, an influence he extends to the relationship between the Blessed Virgin Mary and Jesus.7 And, for us to consider Jesus to be truly human, this influence must include the self-surrender that von Balthasar has described in his anthropology. This has important Mariological and ecclesiological implications. Within the limits of her humanity, Mary’s self-surrender must be boundless, “with absolutely no (even unconscious) restrictions,” and free from the sin that “gives man the mentality of the private individual” if she is to serve as the school of Jesus’ humanity.8 For ecclesiology, this same unconditional “yes” to God’s will makes Mary “an inimitable, yet ever-to-be-striven-for embodiment of…faith” that represents an example of discipleship for the Church.9 Moreover, if we treat her example as foundational, then we must agree with de la Potterie that as disciples, “it is more important to be a believer than to be an apostle” in light of the fact that Christ entrusted his disciple to the nurturing of his mother first, and only after his resurrection did he send him out to preach the Gospel.10

The act of self-surrender informs how von Balthasar understands the relationship among the three persons of the Trinity at Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross as well. At Calvary, Jesus surrenders to the will of his Father, acknowledged the evening before at Gethsemane when he prayed, “’My Father, if this cannot pass unless I drink it, your will be done’” (Mt 26: 43 NRSV), and moving from readiness to “allowing himself to be used.”11 However, Jesus self-surrender – unencumbered by a sinful nature that flinches and holds back as explained above—achieves something unique for history, accomplishing what no mere human could. He gives all. As von Balthasar writes:

Jesus’ total surrender of himself after his distribution at the Last Supper is so definitive that it can in no way be retracted in an effort to retrieve his self-possession, since in the “hour of darkness” he has submitted his fate, the meaning and the form of his redemptive work entirely to the disposition of the Father.

We are meant to see in this Eucharistic sacrifice the economy of the dialectic at work—God the Father, in his infinite love for the world, giving his most precious gift, his Incarnate self in his son Jesus Christ, and that same love driving his son to offer himself back to the Father for the world. Von Balthasar associates this love with the Holy Spirit, having the dual function of being the product of the relationship between the Father and Son in an objective sense, and also the love itself.12 This dialectic between objective and subjective, masculine and feminine, is also present in the Church’s awareness of itself as attested by Lumen gentium.

The dogmatic constitution of the Church, Lumen gentium, witnesses to both an understanding of the visible and institutional Church as Petrine and, in keeping with von Balthasar’s categories, of a masculine character. It asserts the succession of the Church’s episcopal hierarchy directly from Christ through his apostles and, most importantly, through Peter to whom he entrusted his Church (LG 8).13 It also points out the responsibilities of the ministerial priesthood among which are administration of the sacraments that “bind men to the Church in a visible way” (LG 14), and associates these sacraments with the expression of the Church as “an entity with visible delineation” (LG 8). Besides its association of the institutional Church with Peter, it emphasizes the masculine role of its hierarchy when it calls out the “paternal functioning” of the episcopate (LG 21), and exhorts, “{priests}, as fathers in Christ, take care of the faithful whom they have begotten by baptism and their teaching” (LG 28). As Henri de Lubac, the Belgian theologian who worked among the periti at the Second Vatican Council, writes:

The authority of the bishop has an essentially paternal character. If he is head, it is because he is father. And every priest charged with a ministry participates at his own level in this authority and exercises it in the same character.14

Within the context of von Balthasar’s dialectic, this masculine, Petrine character begets the faithful through making Christ known to the Church, which receives it according to its feminine character.15 As an historical entity, it also represents the objectified self-sacrifice and surrender of Christ which creates it, “the universal spiritualization of the Christian people through the presence of the Holy Spirit” and is, therefore, normative for the Church.16 Balthasar would poetically conclude:

The Church fastens the believer—who as a man of the earth would just as well creep along on the ground—to the espalier of her objective order, and on this trellis, he can grow and bear fruits according to his gifts.17

From the visible Church, the person experiences the gift of surrender and, in recognition and appreciation for that gift, honors the giver by giving in return. This fulfills the expectation that the seed of divine life, the freedom of self-surrender, bear fruit and generate new seed so that “what is begotten is one who can beget … God’s deepest intention in creating”18

However, Lumen gentium also sets up a unique place for the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Church into which we can read ecclesiological implications. After much polarizing debate as to how and where to treat the subject during the Second Vatican Council, the Council Fathers chose to include her in its constitution of the Church, acknowledging her importance to understanding the mystery of the Church through her intimate connection with the birth, life, and death of Jesus.19

The text of Lumen gentium clearly emphasizes the feminine aspects of Mary’s role in the Church. It speaks of her “maternity” (LG 61), her “maternal duty” (LG 60), and notes how she is “intimately united with the Church” (LG 63). Other references to Mary contain more subtle, feminine notes that recall von Balthasar. There is a clear recognition that it is through her “belief and obedience” and “undefiled faith” (LG 63) that she was able to bear the Son of God, consistent with the “boundlessness of her ‘Yes’” which with she responds at the Annunciation and at the foot of the Cross.20

The Church, indeed, contemplating {the Blessed Virgin’s} hidden sanctity, imitating her charity, and faithfully fulfilling the Father’s will, by receiving the word of God in faith becomes herself a mother (LG 64).

De la Potterie agrees that the Church’s maternity parallels human maternity in the ways in which it bears, nurtures, and teaches the Christian.21 These many associations with maternity suggest that the Council Fathers understood Mary as representing the feminine receptiveness to God’s will through whom he begets not only Jesus Christ but also, through her maternal example, his Church.

Having examined von Balthasar’s dialectic and its reflection in Church teaching, we can now attempt an understanding of how he reconciles the two as one Church. The Petrine aspect of the Church—its priesthood, sacraments, and Magisterium—constitute the Church’s objective holiness; the Marian aspect of the Church is the response of its members moving “towards the holiness of Christ in the Holy Spirit.”22 Von Balthasar considers the objective Petrine aspect to be functional, the exercise of an office. However, it is precisely this function which, according to Lumen gentium, “unite the prayers of the faithful with the sacrifice of their Head” (LG 28). However, how is it that Mary and the Church gather together for the sacrifice? How does their maternity create the prerequisite receptiveness to surrender? The traditional scriptural basis for Mary’s maternity of the Church helps shed light on the Marian aspect of the dialectic.

On the Cross, the dying Jesus looks to his mother and his beloved disciple and says, “’Woman, here is your son.’ Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother’” (Jn 19: 26-27). De la Potterie has argued that this should not be understood solely as impacting the physical persons of Mary and the beloved disciple, but spiritually as well.23 His analysis of the Greek text reveals that the beloved disciple takes Mary into his home in a more profound and spiritual sense. The word used “signals the beginning of an attitude of faith … a purely spiritual movement.”24 Based on von Balthasar’s understanding of the role of the mother in imbuing the other with what it means to be “self,” and Mary’s contribution to the economy of salvation—her unreserved surrender to God’s will—we can begin to see the implications of Mary’s maternity of the Church. At the foot of the cross, we witness the completion of Mary’s surrender to God’s will. Just as she provided her son with a human testament to what sacrifice of self means, by analogy she has done the same for the Church, beginning with the beloved disciple. The Church and the beloved disciple witness her readiness to accept the will of God, encompassing the joy of her soul at the Annunciation, and the sword prophesied by Simon. It learns true discipleship, the attitude of the believer. And in the life of the Church, we witness this same sacrifice, and become true disciples through the sacrament of the Eucharist. The Church becomes a witness again, as de la Potterie claims, “{to} what Jesus himself announced: ‘And I, lifted from the earth, shall draw all peoples to myself.’”25 Just as the Church is born at Calvary through the bringing together of Mary and the beloved disciple, so it is reborn at the sacrifice of the Eucharist. Jesus’ death on the cross is present to us again as we stand before the altar with our mother, the Church, and submit, in complete readiness, to God’s will for us. Like babes learning to become adults at the foot of their mother, the Christian learns from Mary and the Church.26

Von Balthasar’s dialectic, while useful for looking inward to understand the nature of the Church, can also provide theological context for the Church’s pastoral efforts. Early in his pontificate, Pope Francis I was widely criticized by “conservative” voices in the Church for what appeared to be a softening of the Vatican’s positions on social issues when he said, “We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage, and the use of contraceptive methods.”27 Within the context of his other remarks, and von Balthasar’s dialectic of objective/subjective holiness, I do not believe this to be the case. Rather, Pope Francis is placing Church teaching within the economy of a conversion of heart, the birth of a Christian! He goes on to say, “The proclamation of the saving love of God comes before moral and religious imperatives” (emphasis added).28 In this interview, Pope Francis has pastorally acknowledged what von Balthasar theorizes—that the person must first have that open-ness to the other, in this case God and his saving love, before he can seek to bring himself closer through adherence to Church teaching. How can we expect someone to affix himself to the Church’s trellis if he has not even entered the garden? At the heart of Pope Francis’ pastoral approach is an acknowledgment of the need for receptiveness first, which he claims “fascinates and attracts more” as it is “from this proposition that the moral consequences then flow.”29 The person must come to believe in Christ’s sacrificial love for him first, before he can offer love and obedience in return.

Hans Urs von Balthasar’s dialectic—this “reciprocal relationship” between love and law, subjective and objective, Mary and Peter—provides a theological framework for understanding personal conversion, and the nature of the Church. However, we must not lose sight of the Church’s essential indissolubility. The Church is not Petrine; the Church is not Marian. She is both, yet still one; a Mystery, as the person is a Mystery. Therefore, when considering the Petrine and Marian faces of the Church, we should exercise the wisdom of Solomon in 1 Kings 3:25, and only “divide” her to understand her origins, and not to promote an agenda.

- Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Spirit of Truth, Vol. III of Theo-logic: Theological Logical Theory (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 312; Ignace de la Potterie, Mary in the Mystery of the Covenant (New York: Alba House, 1992), 231. ↩

- Hans Urs Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology IV: Spirit and Institution, trans. Edward T. Oakes, S.J. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 212-215. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology, 212. ↩

- Hans Urs Von Balthasar and Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Mary, Church at the Source, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 111. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Exploration in Theology, 214. ↩

- Ibid, 215. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Mary, Church at the Source, 102. ↩

- Ibid, 104-110. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Mary, Church at the Source, 110. ↩

- De La Potterie, Mary in the Mystery of the Covenant, 230-1. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology, 226. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology, 232-233. ↩

- Second Vatican Council, “Dogmatic constitution on the Church: Lumen gentium,” In Heinrich Denzinger, Enchiridion symbolorum definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum: Compendium of Creeds, Definitions and Declarations on Matters of Faith and Morals. Edited by Peter Huenermann. 43rd ed. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2012. ↩

- Henri de Lubac, The Motherhood of the Church, trans. Sr. Sergia Englund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1982), 105. ↩

- Ibid, 117. ↩

- Dom Anscar Vonier, O.S.B. The People of God (Assumption Press, 2013), Kindle Edition; Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology, 237. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Explorations in Theology, 240. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Mary, Church at the Source, 129, 131. ↩

- Juan Luis Bastero, María, Madre del Redentor (Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarre S.A., 2009), 67-71. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Mary, Church at the Source, 105. ↩

- De la Potterie, Mary in the Mystery of the Covenant, 232. ↩

- Von Balthasar, Spirit of Truth, 315. ↩

- De la Potterie, Mary in the Mystery of the Covenant, 218. ↩

- De la Potterie, Mary in the Mystery of the Covenant, 227. ↩

- Ibid, 234. ↩

- Ibid, 232. ↩

- Antonio Spadaro, S.J., “A Big Heart Open to God,” America, September 30, 2013, http://americamagazine.org/pope-interview (accessed November 25, 2013). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

You have said it well: “The Church is not Petrine; the Church is not Marian. She is both, yet still one; a Mystery, as the person is a Mystery. Therefore, when considering the Petrine and Marian faces of the Church, we should exercise the wisdom of Solomon in 1 Kings 3:25, and only “divide” her to understand her origins, and not to promote an agenda.”

The need is real, among members of the Body, children in Christ, for both of these realities present in the Church – the masculine and the feminine. To make the comparison explicit: as Pope Francis recently said, “Children have a right to grow up in a family with a father and a mother….” (Nov. 17, 2014, the Vatican, at the interfaith colloquium “The Complementarity of Man and Woman”) Both the father and the mother are needed to conceive, both are needed for proper parenting of the child. Both are included in God’s design of humanity – man and woman are called into a oneness defined through their “reciprocal complementarity” which transcends the mere linear addition of their separate gifts and talents. Indeed together, in the sacrament of Matrimony, they become each for the other a unique gift from God, which would lead them to sanctity and to the perfection of parental fruitfulness.

Yet the Church is one – as indeed also the man and the woman become “one” in Matrimony – with a unity greater and deeper than merely of the flesh, through the mystical grace of Christ. And what God has joined together man ought not put asunder! As you wrote, we “divide” the mystery only “to understand her origins, and not to promote an agenda.” I would add here, we also ought not blind ourselves with something worse than a mere one-sided ideology: that being a one-sided and false caricature. The Church is not only not merely a visible institution, she is not a bureaucracy! She is not a business! She is not an NGO! And, the Church is not only not merely a “single-parent mother,” she is not a “the babysitter that takes care of the baby — to put the baby to sleep,” as the Pope also said. The Church is not to become “a Church dormant” (in a homily and by separate letter to his brother bishops in Argentina).

A disciple of Christ must not be a malformed child – not spoiled by indulgence and lack of discipline, nor made rigid with human legalisms – but in the true charity of justice and mercy, he must be led to that fullness of God’s intention:

“until we all attain to the unity of faith and knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the extent of the full stature of Christ… “(Eph 4:13)