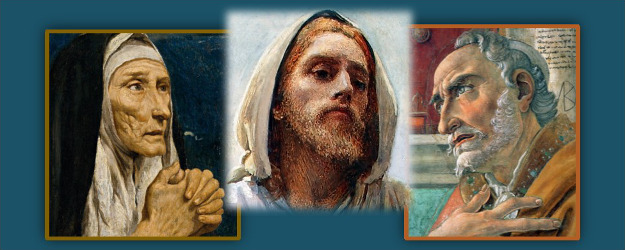

St. Monica, by Luis Tristan (1616); detail from Come unto Me, by Harold Copping (1863-1932); detail from St. Augustine in His Study, by Sandro Botticelli (1480).

Tears manifest the reality of the finitude of man. Tears are most often an expression of being overwhelmed by passion. They can be consented to, embraced, wallowed in, squelched, or avoided. Tears are a silent confession of man’s own reality as a corporal being. Tears are a physical response to the inward experience, and, so, proclaim that man is a unity of body and soul. The very act of crying shows something about who man is. The fact that he can express the movements of his soul in this emotional, corporeal way preaches the truth of what he is as a creature, but his reason for shedding tears, and the extent to which he embraces these tears, also reveals a particular man’s character. Just as the passions are neutral in themselves, so also tears, the expression of a fullness of passion, are neutral as an experience, but may be a curse or a blessing, depending upon the source of the streams of tears. St. Augustine experiences these varieties of tears, and is the beneficiary of his mother’s gift of tears, as related in The Confessions.1

As a Manichean, the young Augustine struggled to find the meaning of his body, and its tendency toward gratification and weakness. The temptation to dissect himself into the different faculties was fed further by the Manichean assumption that all of physical creation was inherently evil, created by an evil deity. This separation of the body and soul seemed to give him some false comfort for a time, excusing his sin as an unavoidable evil at war within himself against which there were no real defenses. If even the good God could not “win” in this battle of good and evil, spirit and matter, how could a mere mortal? Augustine’s own person contained something of a rebuttal for his errors. This multitude of experiences which Augustine threw himself into, body and soul, were experienced fully, body and soul. The experience of shedding tears is one which proclaims this truth about man eloquently. Augustine often analyzes his tears, seeking their source and their end, knowing that the physical presence of the tears speak something of what was moving in his soul.

The first confession of tears to appear in The Confessions presents tears as a curse2 embraced by the infant Augustine. Presuming that the Doctor of the Church can be trusted in his description of his infant motivations for his crying, the source is need, but quickly progressed to self-pity. The infant self-pity is a realization of a real, or a perceived need to which the tears give ample expression. Dependency degenerated into self-sufficiency and manipulation, “I would take my revenge on them by bursting into tears” (conf. 1.6.8). If the need was fulfilled, the tears met their happy end, but if the need was unfulfilled or rejected, the tears became a tool to be wielded in a vain vendetta till the infant tired of tears.

Tears of the infant matured to tears of boyhood. Here, Augustine confesses his tears shed over the fictional Dido (conf. 1.13.20-21). Though these tears might have seemed more mature because they are not directed at himself in self-pity, but toward another; nevertheless, Augustine laments them as sin, because he saw himself truly in need of pity. The tears of his infancy were disordered when they expressed a sinful self-pity, while the tears of his boyhood were disordered because they lacked the inspiration of healthy self-pity over sorrow for sins, “What indeed is more pitiful than a piteous person who has no pity for himself?” (conf. 1.13.21). The seeds of these tears sowed further distraction and a desire to chase after similar tales, beginning an addiction of artificial emotional release, disdaining the truly desirable for the passing distraction. This is the beginning of passions disconnected from responsibility, and pleasure removed from love. In this way, the case could be made that Augustine began his life of distracted desire, pouring himself out upon lesser goods, and settling for the fleeting forgery of love.

The next episode of tears confessed is the young adult tears of Augustine over the death of his friend. These tears, like the vast majority of human experiences, comprise a mixture of curse and blessing. All things, even curses, can become blessings3 in the sight of God’s infinite mercy. These tears were an authentic response to a perceived definitive separation. The separation did not begin with the death of his friend, but with the friend’s baptism which, for the time being, created a great gulf between his friend and himself. The friendship itself was not perfect, “because friendship is genuine only when you bind fast together people who cleave to you through the charity poured abroad in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who is given to us” (conf. 4.4.7). Now that his friend enjoyed the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, Augustine could no longer possess him, mold him, and influence him. The friend, who no longer found his identity in Augustine’s immature love, “with amazing, new-found independence warned me that, if I wished to be his friend, I had better stop saying such things to him” (conf. 4.4.8). The bitter sorrow, which initially might have led to a true charity for his friend, turned in upon itself to self-pity. Soon, it was no longer the loss of the friend which inspired the weeping, but the soul of Augustine which found solace in his own miserly misery. “Miserable as I was, I held even this miserable life dearer than my friend; for although I might wish to change it, I would have been even less willing to lose it, than I was to lose him” (conf. 4.6.11). Augustine’s possessive, co-dependent relationship loss (cf., conf. 4.4.8), leads to grasping at his own experience of sorrow, so that it was no longer a human being in the image and likeness of God which he clung to, but the very expression of desolation. The chosen misery spiraled downward, solidifying into a living experience of hell, which is eternally chosen misery separating the soul, not from the image and likeness, but the very presence, of God himself. In the midst of this curse, a merciful gift is revealed. The experience of death as sorrowful and fearful challenges his Manichean beliefs. His friend’s death is not experienced as a liberation—although it truly is, because of his baptism—but as a curse, that curse which Adam deigned to test when he grasped at the forbidden fruit. In Christ’s redemptive blood, the curse for the friend becomes a blessing of greater intimacy. In time, Augustine also revisits these self-infected wounds, now healed. These wounds, placed in the light of the glorified wounds of Jesus, become trophies of merciful love, glorified as Augustine himself converts from glory to glory (2 Cor 3:18).

The gift of tears is a fruitful experience of crying, rooted in an experience of an encounter with God. The first to manifest this gift in The Confessions is St. Augustine’s ever faithful mother, St. Monica. Monica’s desperate prayer for her son could not be expressed in words, or even in silent sighs of the heart, but poured forth in tears, “O Lord, you heard her and did not scorn those tears of hers, which gushed forth and watered the ground beneath her eyes whenever she prayed” (conf. 3.11.19). Like Hannah, the mother of Samuel, who poured out her prayer beyond words for the gift of a son (cf., 1 Sm 1:12-18), Monica became the spiritual mother of her son in the tears she shed for the spiritual birth of her son. “I can find no words to express the intensity with which she loved me: with far more anxious solicitude did she give birth to me in the spirit than ever she had in the flesh” (conf. 5.8.16). The source of Monica’s tears was a heart full of generous intercession for her son. Her tears were sown in sorrow, but the harvest was abundant. Even in her lifetime, Monica’s spiritual motherhood bore fruit in the lives of Augustine’s friends (conf. 9.4.8). The blessings of her gift of tears flow through the centuries, as her converted son’s own intercession and writings continue to nourish the Church.

Augustine’s tears of contrition and surrender to the Lord sprang from the fruits of his mother’s intercession. After an intense wrestling with himself, and with God’s call, the encounter with “Lady Continence” called him to true vulnerability. The encounter with the grace of conversion caused a great restlessness in the already restless heart of Augustine, culminating in “a heavy rain of tears” (conf. 8.12.28). These tears, truly a gift of the Holy Spirit, produced in Augustine that which he could not bring about for all his struggle, the gift of conversion. The tears are a prayer beyond his own prayer. The famous rhetorician finds the acceptable prayer, not in glorious speech, but in humble, vulnerable outpourings having their source in the gift of grace. The prayer beyond speech uses the bodily reaction to the passions, the very part of himself Augustine sought to escape in the Manichean heresy. The tears, as a gift of prayer, cease and give way to joy rooted in a heart fully surrendered to Christ.

Typically, the gift of tears refers to a gift of contrition, but tears can be a grace given in other encounters with profound grace. The conversion from sin to grace is profound, and often a moment of tears in this vulnerable encounter, but the conversion from glory to glory (cf., 2 Cor 3:18), with ever deeper encounters with God’s love and mercy, also can be accompanied with tears. Tears become a part of Augustine’s prayer after his conversion, as he encounters the beauty of the Church’s prayer, “… I wept the more abundantly, later on, when your hymns were sung …” (conf. 9.7.16). These tears had an element of contrition and praise of God’s merciful, unrelenting love, but it was prompted by the encounter of the beauty of the Church, the faithful Bride at prayer. Augustine, now a part of the Bride, speaks in the language of the Song of Songs, of the Bridegroom’s fragrance, and his own past of unwillingness to be drawn into the footsteps of the Divine Lover. “Yet, at that time, though the fragrance of your ointments blew so freely abroad, we did not run after you …” (conf. 9.7.16).

Tears can also be a prayer of total surrender to God’s will, which is beyond our own understanding. This can be seen in the illustration of Augustine’s reaction to the death of his mother, Monica. This episode included tears with a variety of sources, but the end result is the same: trustful surrender to a loving Father after a purification. Augustine held back his natural tears at the deathbed of his mother (conf. 9.11.27). After her holy death, detached from all her earthly desires, Augustine, too, seemed to benefit from his mother’s virtue, even in death. He withheld his tears (cf., conf. 9.12.29), and was thus present to the needs of others, helping his son, Adeodatus, look to Faith for comfort, and using his gift of rhetoric to teach his friends (conf. 9.12.32). Though the tears themselves were dry, his interior was in torment. He wrestled with himself, as a man attached to those he loves, and with the human condition which—as a result of sin—includes the separation of death. The tears finally came in the secret encounter of Augustine with his heavenly Father. These tears were consoling. The tears themselves were not the source of consolation, but the One to whom the tears were poured out,

… I found comfort in weeping before you, about her and for her, about myself and for myself. The tears that I had been holding back, I now released to flow as plentifully as they would, and strewed them as a bed beneath my heart. There it could rest, because there were your ears only, not the ears of anyone who would judge my weeping by the norms of his own pride. (conf. 9.12.33)

This became, then, an act of humility, an act of surrender to the Father. Whether the human motivation for these tears was rooted in a sinful attachment, or not, through grace, these tears became a prayer for his mother (conf. 9.13.34).

As the Psalmist knew, it might be argued that these tears were not a gift of prayer, such as the tears of compunction shed with a humble and contrite heart (cf., Ps 51:17). In the piercing, redeeming light of the Incarnation of Christ, all that is good in human experience is elevated and united to the humanity of the Word made flesh. Jesus shed real human tears at the death of his friend Lazarus (cf., Jn 11:35). These tears, welling up from the heart of Jesus, were not despair or self-pity, but a sorrowful, loving encounter with the state of man after the Fall, which allowed death to have power over man. Augustine’s tears over his own mother’s death, when brought into that encounter with Jesus, were then sanctified, and became a fruitful prayer for his mother, who shed so many tears of intercession, which repaid the widow’s mite poured out so many times over his own soul. A Christian who mourns the loss of a loved one does not sin in the mourning itself. When the pain of the separation is united to the pain of the Crucified One, it can, and will, be healed and glorified in the heart of the mourner, and in the soul of the one who is mourned. Thus, even the wounds and curses brought to birth in sin, can be made new in the gift of grace.

- Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions, trans. Maria Boulding, OSB (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 1997); all citations from The Confessions come from this edition and will simply be given in the body of the essay. ↩

- A curse, in the sense I am using it, is an embraced disorder which tends toward paralysis of virtue growth. ↩

- Blessings, as used in this paper, refer to embraced graces which lead to greater freedom in human flourishing. ↩

Thanks for this lovely pastoral and historical study on the gift of tears. Over the years I’ve witnessed many people’s tears in response to the movement and presence of God. These are scared and life-changing moments. I would love to read a comparable reflection on the gift of tears in the experience of Saint Ignatius of Loyola.

Respected Rev.Sr. Thanks for your meaningful and inspiring sharing.

God Bless you