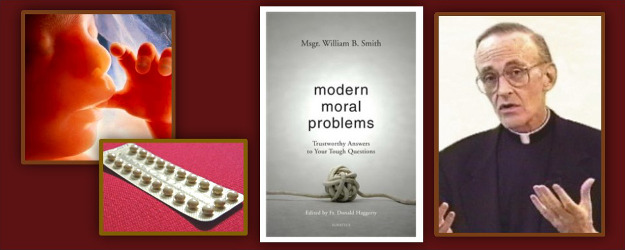

The following are excerpts from a new book which is a compilation of the writings of Msgr. William B. Smith who was a regular contributor to Homiletic and Pastoral Review, from October 1992 to July 2005, for the magazine’s “Questions Answered” column. Included here are the Introduction of the book, and part of a chapter on “Contraception as a Lesser Evil.”

Modern Moral Problems

By Msgr. William B. Smith

With an Introduction, and edited by,

Fr. Donald Haggerty

(Ignatius Press, 2015)

Introduction

Msgr. William B. Smith (1939–2009) was a well-known and highly regarded moral theologian in the United States during the difficult decades of theological struggle in the Church following the Second Vatican Council. Ordained for the Archdiocese of New York in 1966, he was sent, after a brief stint in parish work, to the Catholic University of America, where he attended graduate classes taught by Fr. Charles Curran. By that time, Fr. Curran had achieved notoriety as a zealous organizer of public dissent against Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae condemning artificial birth control. Later, after a Vatican investigation in the 1980s, Curran lost his license to teach theology at any Catholic institution. Msgr. Smith liked to mention on occasion that Fr. Curran was a significant influence on his own thought—precisely to counter and refute aberrant positions in moral theology. After completing his doctoral studies, Msgr. Smith began a long career of 37 years teaching at New York’s major seminary until his untimely death in 2009. He taught continually there until the last weeks before his final illness.

During those years, he became a founding member of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars, which was established in the 1970s for the mutual support and collaboration of scholars faithful to the Pope and the Magisterium. He worked extensively for the pro-life movement in the United States, giving countless talks all over the country and keeping the protection of human life a first-priority moral issue. He was a consultant to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) as well as a primary advisor on moral matters to Cardinals Cooke, O’Connor, and Egan in New York. He served on ethics committees in a number of New York Catholic hospitals. He was a steady presence in a Westchester County parish on weekends, but he was also very close to Mother Teresa of Calcutta’s Missionaries of Charity and to the Sisters of Life. He served as a weekly confessor and spiritual guide to the Missionaries of Charity for 28 years; and, at the personal request of Cardinal John O’Connor, he gave weekly conferences in moral theology to the Sisters of Life for two decades.

While never writing a book, he published numerous articles in theological journals and established himself in the 1970s and ’80s as a premier voice of Catholic faithfulness in the gritty arena of moral theology.

His strong suit was an uncompromising fidelity to the Magisterium and to the Catholic moral tradition. His articles show a particular ability to measure the weight of tradition against more questionable, recent approaches to morality. In areas of medical ethics, for instance, he displayed expertise and great care, consistently basing his arguments on authoritative sources. His appeal as a writer, however, went beyond the clarity of his moral arguments. He wrote with verve and wit; he was neither timid nor tentative in exposing the foolishness of error. One might surmise that his writings were motivated by a profound sense of the harm done to lives when evil choices are rationalized.

The collection contained here is a selection of questions and answers submitted to Msgr. Smith and published in the monthly Homiletic and Pastoral Review between October 1992 and July 2005. The variety of questions and responses spreads far and wide over the course of these years. For the most part, the selections for this collection concentrate on questions of moral matters, with occasional items of sacramental interest. In many cases, the issues and responses are examples of what has been called, in the moral tradition, the exercise of casuistry. The term casuistry refers to the study of cases involving particular moral dilemmas that require resolution. At times, such matters are without a current clear teaching in the Church. The answers of Msgr. Smith are presented with careful awareness of distinctions and possible ambiguities. They display, as well, his zest and vigor for a lively rejoinder. These concise responses to still relevant moral questions are accessible to any informed Catholic today; undoubtedly, they will continue to interest new generations of priests. Even knowing an answer, one may find oneself enjoying Msgr. Smith’s broad range of references and his pungent prose.

The encyclical Veritatis Splendor was issued on August 6, 1993, less than a year after Msgr. Smith began to write his monthly contributions to Homiletic and Pastoral Review. It was among the most notable writings in the pontificate of Pope John Paul II. Addressing fundamental principles of moral theology and the incompatibility of some contemporary moral approaches with Catholic theology, it applied a broadside blow to the dissenting moral theology that had gained much ground in the previous 25 years. The collection of these questions and answers can be read now as an expression of a more confident turn in moral theology that ensued in the years following Veritatis Splendor. Msgr. Smith and like-minded theologians found in the encyclical a vindication for a sound Thomistic foundation in the Catholic moral tradition. Many of the responses contained here make explicit use of principles found in the encyclical. The title of the encyclical, moreover, The Splendor of Truth, evokes the attractive radiance that truth offers to those who seek it with honesty. One can sense throughout the answers in this collection a profound respect for truth as an ultimate value.

Msgr. Smith’s honesty and love for truth was a characteristic mark of his personality. I remember, as a seminarian in his classroom, that we used to joke that he was unable to give his oral true-and-false quizzes properly. Anytime he read a false statement, he managed to give it away with a cough or some stumbling over a syllable or word. This attachment to truth was a deeply rooted commitment in him.

On the other hand, what he really disliked in the various expressions of dissent in the Church was an inherent dishonesty. In his view, dissent from authentic Catholic teaching always combined some poisonous chemistry of dissimulation and personal pride. His own approach to teaching and public talks was to represent the Church’s teaching with clarity, never to minimalize it or make excuses for it, never to allow distortions of it. He was not one to posture with contrived sincerity or assume the correctness of a conviction simply because it was convenient or offered a chance for some victory in debate. As is evident in many answers here, he often turned with deference to a greater authority than his own intelligence in seeking his final resolution of a moral matter.

Sometimes we mistake being faithful with mere submission to obligations in the Church. But, of course, faithfulness is not simply obedience in itself, except superficially. Faithfulness is an expression of love, a fruit of personal love for God. The intellectual apostolate of Msgr. William Smith is inseparable, I believe, from his spiritual life. His convictions paralleled his sense of vocation.

My initial contact with him was to observe him offering Mass at a Missionaries of Charity chapel in the Bronx, and, in a sense, my view of him never changed from that time. In the 25 years I knew him, he was, first of all, a spiritual man, a prayerful man, whose daily presence in prayer at the seminary or at Mass radiated a love for these actions, a man whose soul had long been given to God. His thought when dealing with serious matters of theological controversy followed in a very spontaneous manner from this fidelity to his Lord. He was a man of God first, and then a theologian teacher. May the Church continue to produce priests of this quality and character.

___________

From a chapter from Smith’s book on:

Contraception as a Lesser Evil

Question: This is, not a single question, but a summary of questions invoking the justification of, or counseling the “lesser evil.” Isn’t contraception better than abortion? Contraception preferable to family break-up? Better for a Catholic hospital to provide contraception and sterilizations than cease to exist? Does not a truly proportionate reason modify lesser evils?

Answer: This manner of posing moral dilemmas has a modern and frequent usage that bears little resemblance to the careful distinctions of classic moralists.

First, the expression “lesser evil” can have several meanings. Joseph Boyle, at a Dallas workshop for bishops (1984), noted that “lesser evil” can refer to the difference between light and grave matter, an unjust and more unjust state of affairs, or a morally right, but difficult, choice compared to undesirable consequences, but not morally required. Boyle’s basic critique is that of the prevalent misuse of the so-called “lesser evil” by proportionalists.1

Germain Grisez notes: “Classical moralists were not of one mind on the permissibility of counseling the lesser of two moral evils.” Grisez is correct that the classical moralists who did approve of “counseling the lesser evil” assumed as a condition “that the other was already determined to carry out the greater evil.”2

Grisez himself correctly argues that it is always “direct scandal” to encourage anyone to do any moral evil in order to avoid any non-moral evil, however great. To intend a lesser sin is, obviously, to intend sin and, thus, give scandal. Therefore, to counsel a “lesser evil” can only be permissible when, rather than lead a wrongdoer to choose an evil, the counselor only tries to persuade the other to bring about less harm.3

Classic and reliable moralists, such as Hieronymus Noldin, S.J., Albert Schmitt, S.J., and Marcelino Zalba, S.J., teach the same.4 Henry Davis, S.J., in his Moral and Pastoral Theology, goes to great lengths to make proper distinctions while defending Jesuit authors against charges that they endorse violations of the “end justifies the means.”5

Fr. Ludovico Bender, O.P., presents the most stringent analysis: to choose an action as the lesser of two evils is illicit (if both are moral evils). One evil does not become good simply because a greater evil could have been chosen. Bender argues this is a non-existent dilemma wherein one is required to choose between two sinful acts. One can always refrain, he argues, from positive action altogether when, if to do neither, would itself be no sin. If serious damage results from this omission, the individual would not be responsible for such consequences because no one can be morally required to sin.6

Is it permissible to advise a person bent on committing sin to commit another but less grave sin? Bender argues not! For to advise or suggest is to “induce,” and there is always scandal in that. However, to dissuade another from part of a total evil already planned, and insofar as the wrongdoer cannot be deterred from the complete wrong is, for Bender, a good deed. The classic example: to suggest to a thief, who wants to kill the owner and take his property, to take only the money, is not advising theft but advising against murder. The theft, already decided upon, is not caused by the advice: this particular advice is to deter the thief from murder, also decided upon.

Thus, he argues that there is a difference between counseling the lesser of two evils and advising against part of a proposed evil. The first employs an evil act for a good end; the second, a good act for a good end.7 The subtleties and distinctions of classical moralists are a far cry from the quantitative and careless comparisons of most proportionalists. In my opinion, old and new authors can use the same terms (“lesser evil”) but use them in ways that have no resemblance to each other. Grisez’s brief treatment is a good example that clarifies modern dilemmas instead of confusing them.8

Thus, for example, the Catechism teaches: “The gravity of sins is more or less great: murder is graver than theft. One must also take into account who is wronged: violence against parents is in itself graver than violence against a stranger” (no. 1858; cf. also nos. 1854–64; VS, nos. 69, 70; Reconciliatio et Paenitentia, no. 17).

It is surely true that murder is graver than theft. But, theft (grave or light) is never a “good,” and is only a “lesser evil” by comparison to something worse. This kind of “comparison morality” has the quantitative attraction of damage control—but morally, it is the wrong comparison.

The morally relevant comparison presented to moral choice is the basic freedom of contradiction (freedom of exercise): to do or not do the same thing under the same circumstances. Thus, to steal or not steal $1,000 from a specific person. To compare this with other acts (other and different moral choices)—this owner or this company grosses one million dollars per annum or, at least, I am not killing him when I steal—these other facts (choices) do not change the moral species of grave theft. Morally, it is the wrong comparison and easily misleads to an uncountable calculus of subjective reasons in place of an objective moral principle.

Thus, the question is posed: Is not contraception “justified” as a “lesser evil” to avoid an abortion or a family break-up?

John Paul II’s encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, addresses this question. Some might try to justify contraception as an abortion preventative, but this is an empirical illusion. Widespread contraception does not reduce abortion; indeed, it is in societies where contraception is most available that permissive abortions flourish.

Although contraception and abortion differ in nature and moral gravity—abortion destroys a life (Fifth Commandment) while contraception opposes the virtue of chastity in marriage (Sixth Commandment)—despite these differences they are closely connected “as fruits of the same tree” (EV, no. 13). They share an anti-life mentality, a distorted refusal to accept responsibility in matters of sexuality; and a self-centered concept of freedom that sees human life as an obstacle to personal fulfillment (EV, no. 13). Thus, abortion comes to be seen as back-up for failed contraception. Acts that are intrinsically evil—as both contraception and abortion are (VS, nos. 47, 80)—never become “good” nor permissible when done with the intention of bringing about some “good” or lesser evil. Intrinsically evil acts are, in the end, objects of human choice that, by their very nature, are “incapable of being ordered to God because they radically contradict the good of the person made in his image” (VS, nos. 79, 80).

Lastly, there can be a complete confusion of categories when some argue on the basis of the “lesser evil” that a Catholic hospital can “materially cooperate” in non-therapeutic sterilizations (and, perhaps, other proscribed “services”) considering that if the Catholic hospital does not merge, or co-sponsor, or joint venture prohibited services, that geographic area will be underserved by a diminished, or disappearing, or closed Catholic facility. The argument for cooperating in what the Catholic facility is prohibited from providing often confuses loss of money (a real loss, but not a moral evil) with non-therapeutic contraception and/or abortion referrals (moral evils).

Morally, this is not a “lesser evil” case at all. In fact, when a Catholic facility begins to provide so-called “services” that it is ethically and institutionally opposed to, one could ask whether the loss, reduction, or closure of such a facility is only a qualified loss since it already institutionally contradicts its own ethics—itself a scandal. In terms of Catholic witness, it is not clear what “good” is lost or “lesser” when a religious institution self-contradicts its religious identity and its religious purpose.

- Joseph Boyle, “The Principle of Double Effect: Good Actions Entangled in Evil,” in Moral Theology Today: Certitudes and Doubts, ed. Rev. Donald G. McCarthy (St. Louis: Pope John Center, 1984), p. 257. ↩

- Germain Grisez, Living a Christian Life (Quincy, Ill.: Franciscan Press, 1993), p. 237. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See H. Noldin, A. Schmitt, and G. Heinzel, Summa Theologiae Moralis (Rauch, 1961), p. 105, n. 113; and Marcellino Zalba, Theologiae Moralis Compendium, vol. 2 (Madrid, 1958), pp. 112–13. ↩

- Henry Davis, S.J., Moral and Pastoral Theology, vol. 1, 6th ed. (London, New York: Sheed and Ward, 1949), pp. 247; 339. ↩

- Fr. Ludovico Bender, O.P., Dictionary of Moral Theology (Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1962), pp. 705–6. ↩

- Ibid., p. 706. ↩

- Cf. Grisez, Living a Christian Life, pp. 237–38. ↩

Chapter 7, “Forming a Correct Conscience” in my book “Sex and the Marriage Covenant: A Basis for Morality” (Ignatius, 2005) was greatly influenced by my listening to Msgr. William B. Smith, and I was happy to submit it to him for review. In it, I reviewed the teaching of Lumen Gentium 25 for the conditions under which the teaching of the Pope must be accepted as an exercise of the Ordinary Magisterium, and I showed how St. John Paul II had fulfilled those requirements with so many quotations that Msgr. Smith called the list “ad nauseam” which I took as a compliment. One of those quotations is highly relevant to the papal airplane comments of Feb 17-18.

JFK: On 17 September 1983 he made a statement as strong as that of Pope Pius XI in Casti Connubii. To a group of more than 50 priests who had participated in a seminar on responsible parenthood, Pope John Paul II made this statement:

JPII: “In a word, contraception contradicts the truth of conjugal love. Contraception is to be judged objectively so profoundly unlawful as never to be, for any reason, justified. To think or to say the contrary is equal to maintaining that in human life situations may arise in which it is lawful not to recognize God as God. (SMC 124)

What did Msgr Smith mean by “keeping the protection of human life a first-priority moral issue?” For many that meant being against abortion. This limited view of Catholic Social Teaching did much damage to the wider meaning of “protection of human life”.

“In his view, dissent from authentic Catholic teaching always combined some poisonous chemistry of dissimulation and personal pride.” This is a universal statement that I find hard to justify. How can one be certain that what one’s views are coming from human pride?

……and what part of “keeping the protection of human life a first-priority moral issue?” limits “protection of human life” to abortion only ??? Pro-abortion ‘catholics’ can attempt to make this distinction but clearly it is a distortion.

…… where else would one’s views, if disagreeing with the Magisterium, come from but pride in their own intellect or reasoning?

Exploring the basis of what constitutes the radical goodness of being open to life is about exploring an anthropology which shows that it is natural to man, male and female, to marry and to participate in the mystery of procreation: of cooperating with God in bringing into existence a human person. This anthropology tells us that the laws of human fertility are a personal expression of the intimate dialogue of the Blessed Trinity: being open to life is a kind of “enfleshed” expression of the love between the persons of the Blessed Trinity that expressed itself in the act of creation. In other words, human being is so constituted that the transmission of life manifests a conscious participation in the unconscious law of human being: the law that reigns throughout the structure of the universe but in man and woman shows itself to be an expression of personhood (cf. Chapter Three of Volume I-Faithful Reason, 2016). Thus the marital dialogue of a man and woman takes up all that constitutes the full dynamic of being man, male and female and, at the same time, takes it up out of love: a love that only God can bring to exist. Thus, while it seems possible to discuss, as we do, the intricacies of what makes love possible or what frustrates its expression – it becomes clearer and clearer to me that being open to life is a grace given to married people for their conversion: to turn them to God and to express the reality of their life as turned to God. In other words, it is especially clear to me that marrying late and having ten children in more or less ten years of marriage was a miraculous triumph of the grace of God over every kind of calculating selfishness. It is a sign that the cross and resurrection are lived in the flesh of daily life; and, at the same time, the Christian life is not an individualistic vocation. In other words, being open to life expresses a full participation in the dialogue of salvation: the dialogue between husband and wife and the presence of God; and, at the same time, the concrete expression of God’s providential shows itself in the day to day events of marriage, family, home, work, and their intricate difficulties.

The full expression of the Christian life, founded on the gift of faith, the mystery of the Church and her sacraments, the presence of the Christian community and the providential love of God are indispensable to the realization of the vocation to marriage (cf. Volume III-Faith is Married Reason, due out in 2016). It is increasingly clear to me, then, that the vocation to sacramental marriage is a particular expression of how the grace of God brings about a social good: a good which transcends the individualism of selfishness and brings about a communion which enriches us all. It is as if, in other words, the “new man” of the Gospel is indeed new: a man whose conversion makes visible God’s creation of the domestic church.

In certain conflict cases the the moral object may be evil but avoiding it brings about another evil. . There are many cases in casuistry o confessed in reconciliation the principle would seem to apply but finally does not since the person NEED not choose either of the evils involved. . The Catholic church constantly teaches the truths necessary to avoid such sins in the first place ( truths about chastity) and promote the corporal and spiritual works of mercy among the faithful to avoid any sin in the future. But in many cases another evil or sin cannot be avoided yet not intended. Here follows the principle of Double effect. when an action causes both a good and evil affect. . No one is allowed to advise another person to will any sin for here that advisor has sinned gravely. It is correct to adhere to the fundamental option and advise a person to live a life of love. I suggest reading 1st and 2nd Corinthians of Paul, Apostle to combat any evil or conflicts.

I hope the Monseignor had at least some problems with Veritatis Splendor. We Catholics come across often as a mutual admiration society with no criticism allowed even when it is warranted.

In VS St. John Paul II called slavery and deportation intrinsic evils. Here on the contrary is Leviticus 25 with God speaking in the first Person imperative:

44

* The male and female slaves that you possess—these you shall acquire from the nations round about you.

45

You may also acquire them from among the resident aliens who reside with you, and from their families who are with you, those whom they bore in your land. These you may possess,

46

and bequeath to your children as their hereditary possession forever. You may treat them as slaves. But none of you shall lord it harshly over any of your fellow Israelites.”

…………..

Oddly enough,we should hope there is slavery wherever there is also Levitical like nomadic cultures as in the uncontacted tribes of Peru and Brazil. Nomadic cultures need slavery to process petty criminals, large debtors and war captures….otherwise nomadic cultures would execute all three for lack of institutional prisons. Take your pick…execution or slavery.

To write that deportation is an intrinsic evil in a blanket non nuanced manner is also a problem. Europe right now is deporting refugees it deems as those seeking mainly a more affluent income. That allows them to take in those mainly fleeing the horrors of living in danger with income secondary.

Italy after Veritatis Splendor deported two muslim students back to North Africa for plotting to kill Pope Benedict. Pope Benedict did not try to stop that deportation.

St. John Paul II called torture an intrinsic evil and yet Church courts used light torture for centuries….bones e.g. could not be broken. In fact the present catechism description of torture is so worded that it logically opposes Christ making a whip of cords with which He drove the money changers out of the temple. We lack a critical orthodox office at the Vatican that can rightly criticise such non infallible papal mistakes or catechism mistakes. China .e.g. must see Catholicism’s anti death penalty campaign by the last three Popes as a destabilizing of order…belief and Popes from 1253 AD til 1952 agreed with the Chinese. We’ve placed an unnecessary block to conversion in millions of Chinese minds with a pet, non infallible prudential opinion in ccc #2267 which Pius XII would not agree to if you’ve ever read him on the death penalty….and prisons in his day were much less escapable than those of the now two largest Catholic areas…Brazil and Mexico.

We need Vatican office criticism of our documents that is not dissent from the infallible but is dissent from non infallible sentences and paragraphs that must look like nonsense to well educated non Catholics worldwide…Asian and otherwise.