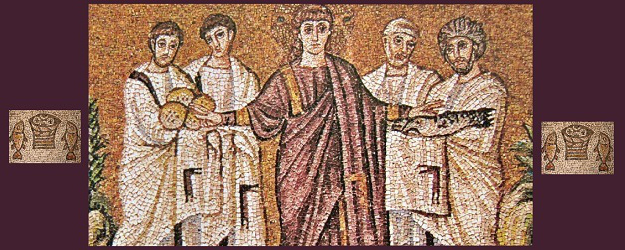

Mosaic of Christ and the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes

(Unknown artist, 6th Century, St. Apollinare Nuovo Church, Ravenna, Italy)

Jesus has a peculiar, almost provocative way of opening up the deeper recesses of prejudices for inspection. In the New Testament, this is often by way of a rabbinical question. “You ask by what authority I make these proclamations: I will ask you by what authority the Baptist came preaching repentance.” Many harbored doubt about the merits of John’s mikvah, or his claim (like Saint Anthony) to announce God in and to the wilderness, and such doubts left them singularly untouched by his declaring the Lamb of God when at last he came. Their hearts could not recognize John’s authority, and in turn, they could not be fed by the Bread who had come down from heaven.

A question of authority is what stands out in the miraculous mass-feedings with paltry loaves and fishes. These miracles—even more than the casting out of demons—underline the “Our Father” in which Jesus taught implicit entrustment, and they anticipate the Church’s mission to “feed my sheep” with heavenly manna. As Jesus reiterated from Isaiah, “Why do you labor for that which does not satisfy?” since man lives firstly on the bread of God’s word. It’s a question of authority, for when the fed masses rose up to make him king, Jesus so deplored the leaven of their unbelief, that he would perform this miracle only twice.

Needing to eat demonstrates we are not gods: even arch-atheist Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) said so: “…the belly is the reason why man does not take himself for a god” (Beyond Good and Evil, ch. 4, aphorism 141). Unfortunately for Nietzsche, the mind is the reason why man does.

Nonetheless, does being fed—in the wilderness of John’s locusts, no less—only go so far as to suggest the provident provider, or provenor, is but a king, one with hidden barns and wise stewards? A far lesser thing than this staving off the storms of hunger—the becalming of stormy seas, which was enough to make truer souls wonder if Jesus was even a man. And they were right to grasp at the sign, and to wonder beyond their own nature.

Jesus put the question of authority this way: what is more difficult to say—“your sins are forgiven” or “be healed of your lifelong infirmity”? Neither benediction is possible to man; both are equally earth-shattering. But the insincere and unbelieving—as scribes were, albeit versed in the divine word—find it easier to mimic authority by saying “the Lord be with you” than to demonstrate it by healing a palsy. So as a testimony against unbelief, and to edify the belief of others, Jesus simply told the afflicted man to get up and walk. That settled his authority.

How then does the question of authority—whether over the physical world, its needs, its entropy, its deficits, or over the spiritual world, its thoughts and motives of the heart—pertain to the feeding of the masses? Had anyone questioned Jesus’ authority in performing those miracles? To mistake his authority as of a king, no doubt as also a prophet with special dispensation from God, is deficient enough—though it does, at least, acknowledge that something absolutely stupendous had happened, creating something from nothing. But we moderns question the very actuality of miracles of which Jesus was author and, by so doing, vitiate the authoritative testimony itself.

There are deep things at work here. In a boat one day after some long labors, the disciples were hungry. In their whining, Jesus found a teaching moment to remind them of these two miracles, asking how many baskets of uneaten food were taken up, in the one case, of seven loaves feeding four thousand; the other, of an additional thousand fed with two fewer loaves. The latter miracle, against a greater discrepancy between need and supply, provided far more over-abundance than the former. The not-so hidden message: where need abounds, grace—even miraculous grace—more greatly abounds. Saint Paul would come to apply this to the privation of sin itself.

We must unavoidably conclude that Jesus performed two great, mass-feeding miracles with the purpose of teaching this trenchant lesson, to “beware the leaven of the Pharisees,” which he repeated for emphasis in the boat. To teach that his is the authority over grace itself, and that the leaven of unbelief, that afflicted rabbis, is a disbelief that grace has any authority beyond mere serendipity. Thus, they were not even able to answer whether the Baptist had acted by grace, or by presumption.

A disturbing trend lies now among scribes of modern religion, those often charged or delegated with the education of children, or the formation of their teachers. It is the trend of disbelieving the miracles of Jesus, or (what is really worse) “explaining them away,” (or worse still) minimizing their testamentory impact. The feeding miracles lead the pack for the dissemblers of grace. To them, the “miracle” at play was under human authority: the opening of neighborly hearts to share hidden stashes of snacks, trail mix, oranges, and other collations, which they had marvelously packed for the impromptu journey of unknown duration. Never mind that folks in clutches, and then in droves, were caught up in the words of Jesus as he wandered farther and farther afield, in order to have them “come aside” and see something. It’s they who had foresight to pack for a long sojourn, and had the wool over Jesus’ eyes.

It is sometimes conceded, to staunch the whiff of disbelief, that a multiplication did occur; but still a greater miracle (or one more pertinent to today’s positivist mind) was the spontaneous sharing of such copious amounts that very bushels of scraps should materialize! These hold that baskets appeared out of thin air, rather than admit that, for the theory to work, at least a dozen folk carried empty wickers into the wilderness, foodstuffs hidden under their cloaks. Well enough, in the presence of miracles the believer will take no issue with baskets materializing (along with thousands of loaves and fish); but he does take issue with minimizing the miracle that really did occur: a creation of nutritious matter from the ether—and, without a Big Bang, at that.

The turning of friends and neighbors, one to another, in a sharing spirit, out on the road, is no miracle. To bless and help friends and family: even the Gentiles do that, as Jesus said. And there will have been many occasions where a multitude was gathered, ill-provisioned, but managing to make do: the thousands of Brits hunkered in underground rail tubes to survive the Luftwaffe bombing throughout the Battle of Britain. Forty men were trapped in a deep mine in Brazil. There were American prisoners of war left to starve in abandoned Japanese camps near war’s end. The list is inexhaustible; but none instances a miracle in our sense of the word: a suspension of the order of nature—such as conservation of matter—for the provision of aid to one or many souls. The authority of such miracles is not human but divine, as it could hardly be the other way round. What human beneficence can stop the earth from turning? Or raise the dead from rotting?

I am concerned with those in the middle, sitting on the fence as it were, who may nod to there being something inexplicable happening by natural means; but who insist that a greater or comparable miracle is found in the camaraderie and sharing that went on with multiplied provisions. Perhaps, theirs is a cynicism about the animal nature of avarice, even in the face of divine windfalls, for its suspension to imply a miracle. More likely, they are torn trying to keep dissenters in the Church by allowing them their leaven. But this is to ignore the pains Jesus took to review the two miracles in every particular (and nowhere else does he reflect volubly on a performed miracle).

Is it so easy to miss the lesson on the leaven of the Pharisees, and Herod declaring this anti-leaven (antithetical to that which Jesus used to describe true disciples) a subtle poison? Jesus saying “beware” more than once has the ominous ring of God warning Cain: a warning of him that is able to cast souls into Hell. For the two are one—the leaven that is not the seed of truth is the venom of the antichrist. The antichrist really just means “contrary to Truth”; and to mislead the young on these utter gems of God’s intervention in the lives of men, begets moral millstones, and burials at sea! So said the merciful, mild Lord of the little ones.

The last thing a fence-sitter wants to be found doing is teaching his error to the innocent; for that act will only deepen misconvictions, and harden his heart to the fact of undermining didactic and generous purposes God had conceived in his choice of miracles. It would gravitate to the condition of a satrap who, though interested and affected by things that John said and did, could not withstand the lure of his dancing step-daughter. This toxin of caviling over the authority of Christ comes to the same end; the only recourse being to get off this electric fence. For if Christ had authority, why would he not have performed the great miracles he said he did, but rather secretly employed social movements yielding to natural law (as well he may do now)?

Moral teachers and guides, today, seem to have too great a habit of supposing everything within revelation is geared to support their version of the social gospel. As if the final soteriology of Jesus’ coming and self-sacrifice were to unlock the nascent good within the natural order, and thereby pave the road to a rebuilt world or utopia. It is to deny, or neglect, the clear message that this fallen world will pass away; while there is a rescuing from it of souls whose “names are written in heaven,” as Jesus said to counter the pride of any with borrowed authority over evil. Thus, our good works are a testament to eternal values that outlast and outshine the world, and this “working for God,” to use Mother Teresa’s phrase, extends the hope of salvation to others.

May the Church, and all its teachers, see clearly to put the leaven of the Pharisees far behind us, believing always with unadulterated faith in the One, and in the singular things that One has done for men. Amen.

Recent Comments