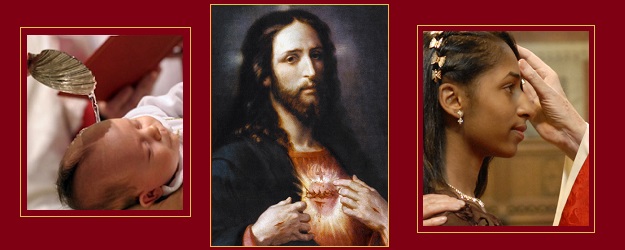

Sacred Heart by Jose Maria Ibarraran y Ponce (1896).

Using concepts derived from Aristotelian philosophy, Aquinas provides a tremendous insight into God’s essence by explaining how the latter is the sole Being whose “essence” and “existence” are one and the same: “… God is not only his own essence, …but also his own existence.” (ST, I, q. 3, a. 4). Moreover, this explanation squares perfectly with God’s divine revelation of his name to Moses as “I Am Who Am” (cf. Ex 3:14). In other words, it is of God’s very essence to exist. He must exist, and cannot not exist. It is as if God is saying to Moses, “Not only is it of my very essence to exist, as the sole Necessary Being, but every other being that exists is a recipient of the gift of existence, bears my imprint, and is sustained in being by me; for, were I to cease willing the existence of a single entity, that being would simply cease to be.”

Further, not only is God the sole Necessary Being, who alone possesses existence, but he is also the absolute ideal and perfection of being in his own divine Life, when considering the hierarchy of being. Thus, we can posit that the more “perfect” a being is, ontologically, the more “person-like” or “personable” it shall be with, of course, the Personhood of the Three Divine Persons constituting the summit and/or perfection of Person and Being, with the former serving as the “perfection” of the latter.

This line of thought describes, in essence, the philosophy of “Thomistic Personalism,” one of the most significant contemporary proponents of which is Fr. W. Norris Clark, S.J. Thus, for the purpose of this article, let us suppose that the philosophical system of personalism is, indeed, among the most accurate reflections and descriptions of ontological being, or metaphysics, and that God’s own Divine Life is the expression, or “personification,” of the absolute fullness and perfection of Being.

In addition to being the author and exemplar of existence, per se, the highest and most perfect expression of which is his own Divine Life, we additionally know, through divine revelation, that God is Love: “Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love” (1 Jn 4:8). Moreover, the one divine nature or essence is perfectly, completely and wholly, possessed by three distinct but not separate divine persons: the Father, who is origin; the Son, who, by way of knowledge (for, the second person is the “Word,” and words are simply expressions of ideas; thus, this “Idea” had to be the Father’s perfect idea, understanding or knowledge, of himself), is eternally begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit, the divine personification of the perfect Love that is mutually reciprocated by the Father and the Son, and who, from all eternity, is spirated from them both. In short, God is three persons Who are truly one in nature, through the unifying bond of charity, or love. Moreover, it is the Spirit who is, properly speaking, the “Love” of God, the “principle of unification.” Furthermore, the very same spirit of love that unites the Divine Persons is the same Holy Spirit, or “principle of unification,” that unites all the baptized members of the Mystical Body to Christ, the Head, and to each other, as members of the one, holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church of Christ.

Based on what has thus far been elucidated, while numerous perfections may be predicated of God, it would seem that life and love not only hold a certain primacy among the divine attributes, but additionally may prove essential to unlocking, or—at the least—shedding light on some of the most significant truths comprising the deposit of faith. Chief among these is the great mystery of the sacred and pierced heart of Christ, from which emerges his mystical Bride and Body, the Church, as well as her entire sacramental life—the center, source and summit of which is the Holy Eucharist. Thus, we ponder the stupendous mystery of the “Circle of Being,” with the Sacred Heart as, simultaneously, the font and apex, the origin and goal, of all the Church’s life and apostolic activity.

Let us begin this exploration by reading St. John’s description of an eye-witness testimony, recounted in his Gospel, of the piercing of the side and heart of Christ:

But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water. He who saw it has borne witness—his testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth—that you also may believe … another Scripture says, “They shall look on him whom they have pierced.” (Jn13:34-35;37, RSVSCE)

After having been placed in a deep sleep, God the Father opened the first Adam’s side, and from that opening was fashioned his bride. Adam, upon waking and witnessing this marvelous work of God, exclaimed:

“This at last is bone of my bones and flesh from my flesh; She will be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man.” (Gen 2:23, RSVSCE).

This event in the life of the first Adam was to serve as a type of Christ, the New Adam, who, after having slipped into the deep sleep of death, Christ Jesus, the New Adam, also had his side opened by the lance of Longinus, a Roman soldier. And, like the first Adam, the Bride of the New Adam, namely his Church, issued forth in the form of blood and water.

While the “blood and water” are deeply symbolic, they retain all of their original properties to this very day, in each and every liturgical celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, which is always and everywhere the very same sacrifice as on Mt. Calvary, transcending space and time, and being made present on every altar throughout the world, in an un-bloody fashion.

Never forgetting the absolute reality of the true, substantial, and abiding presence of the whole and entire body, blood, soul, and divinity of Our Lord, Jesus Christ, at every celebration of the Mass, and in every consecrated host, let us focus our attention, for a moment, on what is being symbolized and represented, in addition to actually being made present. Thus, we shall first turn our attention to the blood of Christ.

The blood that gushes forth from the pierced heart of Our Lord is the very divine life of God, which conveys the grace of God, which can be defined as “the free and undeserved help that God gives to us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature, and of eternal life” (CCC, 1996). Additionally, grace is “a participation in the life of God …{which} introduces us into the intimacy of Trinitarian life…” (CCC, 1997). As mere mortals, we belong to what theology refers to as the “natural order.” While the rational powers of intellect and will, possessed by all human persons, are truly and entirely spiritual in nature, we retain our status as creatures of the natural order. As such, our rational powers, amazing as they are, relatively speaking, simply are not sufficient for us to attain the exalted end for which we were created. What is needed is grace which, properly speaking, flows specifically from the blood of Christ. The late, highly esteemed and prolific theologian, Fr. John A. Hardon, S.J., speaks to this reality in his work, History and Theology of Grace: “When the Scriptures, Fathers, or Councils, of the Church refer to “grace” properly so-called; they mean that gift which is the fruit of the blood of Christ, by which we become Christians and sons of God, are justified, made holy, and enter into heavenly glory. They often oppose grace to nature, teaching that nature must be repaired, made sound, helped, and saved by grace. We are able to do by grace what the lone powers of nature could never do” (Hardon, History & Theology of Grace).

Note: Fr. Hardon’s particular emphasis on the blood of Christ as the source of this gift, or fruit, of grace. Thus, it is through, with, and in the blood of Christ—gushing forth from the pierced side and Sacred Heart of Christ—that we become “adopted” sons in the Son, true brethren of our Lord Jesus, now capable of calling God “our Father,” in the very same manner that Christ, the only begotten Son, calls God his Father! This is more than tremendous—it’s absolutely inconceivable!

One additional note on the relationship between the Trinitarian Life of God—in which we have been invited to participate for all eternity, and the redeeming Blood of Christ—which was shed to merit this grace of divine life. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 2260, reads:

The Old Testament always considered blood a sacred sign of life. This teaching remains necessary for all time (CCC, 2260; cf. Lev 17:14).

The Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life” (LG, 11) and is, in truth, the central sacrament of the Church. All other sacraments, while imparting unique graces for particular situations, ultimately exist to assist the baptized in more fully and actively participating in the Eucharistic banquet. Making present the once, for all, sacrifice of Christ on Calvary, whereby Christ establishes and ratifies the new and eternal covenant in his blood, the work of redemption is carried out, in time, enabling the people of God to exercise the royal priesthood, which was bestowed upon them through their baptism. They are called to offer the spiritual sacrifices of their prayer, work, and suffering through, with, and in Christ, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, to the glory and honor of the Father.

In the Eucharistic discourse, Christ states:

“I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

The Jews then disputed among themselves, saying, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (Jn 6:51-56).

Thus, God extends the “universal call to holiness” (LG, Ch. 5) to each and every person, regardless of his/her state in life; and each individual, moved by the action of the Holy Spirit, is called to give full assent of intellect, or the obedience of faith, to God’s divine revelation of himself, the culmination of which is brought to completion in the coming of Christ Jesus, for, “Anyone who has seen {him} has seen the Father” (cf Jn 14:9). Further, “Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved” (cf. Mk 16:16), provided he “eat(s) the flesh of the Son of man and drink(s) his blood” (cf. Jn 6:53); or, in other words, partakes of the Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist. For, it is through the new and eternal Covenant in Christ’s blood that the grace of divinization—or the conferral of the Divine Life of God—is effected in our souls; thus, we become a “new creation…” (2 Cor 5:17), and “…partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4).

Having briefly focused on the reality of Christ’s blood, particularly as it emanates from his pierced heart, let us now fix our gaze on the water that also gushes forth from the same pierced heart, which represents and brings about the greatest work of God’s merciful love via the sanctifying waters of Baptism.

So much can be said of this first sacrament of initiation, which grafts us like branches to the vine that is Christ, in order that we might bear good fruit. It is, first of all, the sacrament of faith. Despite the reality that the majority of Christians are baptized as infants, the significance of the act of faith that must be made to receive this “first of all the Christian sacraments” is precisely what sets it apart as the sacrament of faith. In the instance of infant baptism, the “act of faith” is made for the child, and on behalf of the child, by the parents and Godparents, who make a solemn promise to raise the child according to the teachings of the Universal Church. The Church, in her perennial wisdom, understands the tremendous danger of withholding, or putting off, the reception of this most fundamental and necessary of all sacraments. Some have put forth the argument that, as the sacrament of faith, the individual should not receive the sacrament until he or she reaches a certain degree or level of intellectual maturation, thereby ensuring that they are receiving the sacrament freely and of their own accord. Yet, the Church clearly sees this sacrament as essential to restoring the newly born infant to the friendship of God, and that through its reception, the child is washed of the inherited original sin of Adam, which is better described as a privation of the in-dwelling presence of God within the soul. Thus, Baptism is necessary for each individual, as every newborn child is born without the life of God in his or her soul. And, because the Church, in her wisdom and goodness, wishes to ensure that each newborn child be afforded the graces of divinization and justification, the faith of the sponsors is accepted on the child’s behalf, and the child, or adult, is grafted to the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church, with Christ our Lord as her head, and Mary Immaculate as her mother and model.

In addition to being the sacrament of faith, it is additionally one of the three sacraments of initiation, along with Confirmation, and the Eucharist. Together, these three “lay the foundations of every Christian life” (CCC, 1212).

Moreover, baptism is similar to the sacraments of confirmation and holy orders in that each of these impart “character,” which is an indelible mark on the soul, which cannot be erased. Thus, once one receives the sacrament of Baptism, one can never lose it, neither can they ever be, as it were, re-baptized. Even should one wholly renounce his faith, and spend the rest of his life persecuting the Church of Christ—like St. Paul, prior to his conversion on the road to Damascus. One cannot, as it were, “shake off” the sacrament of his baptism. Neither would one need to be re-baptized if he were to eventually see the error of his ways and wish to repent.

“The waters of the great flood you made a sign of the waters of baptism, that make an end of sin, and a new beginning of goodness” (Roman Missal, Easter Vigil). Thus, there is a long history of seeing in Noah’s Ark a pre-figuring of salvation through the purifying waters of baptism.

Water, then, is seen as an agent of cleansing and purification, for body and soul. Thus, water is used in the administration of this sacrament of initiation as the “matter” of the sacrament.

The “matter” of a sacrament is whatever “material” is being used in the administration of the sacrament, just as bread and wine are the primary matter of the sacrament of the Eucharist. The “form” of the sacrament consists in the words and actions of the celebrant. In the case of baptism, the form is the “Trinitarian Formula,” which consists of the words: “(Name), I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” being spoken while holy water is lightly poured over the forehead of the infant three times, corresponding with the pronunciation of the names of the three Divine Persons of the Holy Trinity.

It was the great St. Augustine who held that “the justification of the wicked is a greater work than the creation of heaven and earth, because ‘heaven and earth will pass away but the salvation and justification of the elect…will not pass away'” (CCC, 1994). Thus, according to the greatest theological minds ever produced by the Church, God’s mercy, particularly as it is manifested in the justification of sinners, “is the most excellent work of God’s love” (CCC, 1994).

With this being so, it behooves us to make the effort to grasp, insofar as is possible, this theological concept of justification. Justification may be defined as the process by which man is made “just” in the sight of God. This process of being made just, becoming sanctified, “accepting God’s righteousness” or participating in God’s own divine life begins with the redemptive work of Christ, who, from the cross, and specifically by the shedding of his blood of the new and eternal covenant, freely merits for humanity the grace of objective redemption. According to the Council of Trent: “Justification is not only the remission of sins, but also the sanctification and renewal of the interior man” (CCC, 1989).

Yet, while justification is the greatest act of the Father’s mercy, merited by Christ Jesus, and communicated by the Holy Spirit via the Sacrament of Baptism, it additionally depends on the freewill response of each individual:

Justification establishes cooperation between God’s grace and man’s freedom. On man’s part, it is expressed by the assent of faith to the Word of God, which invites him to conversion, and in the cooperation of charity with the prompting of the Holy Spirit Who precedes and preserves his assent (CCC, 1993).

To sum up the conclusions we have thus far come to, we can begin by stating that “life” and “love” are two of the most salient attributes of God, and that these two sides of the same coin, as it were, correspond to the blood and water that gush forth from the side of the sacred heart of Our Lord, as is beautifully depicted in the image given to St. Faustina, which has two rays emanating from Christ’s heart: one red and one white. The red ray represents the blood of Christ, the source of the brace of divine life merited by Christ on the cross, while the pale ray is symbolic of God’s merciful gifts of conversion, the forgiveness of sins, and the resolve to live in a state of sanctifying grace, the habitual in-dwelling of the Holy Spirit as the soul of one’s soul, enabling one to live in accord with the commandments of God.

Having fleshed out the relationships amongst divine life, Christ’s blood, and sanctifying grace, on the one hand; and divine love, holy water, and divine mercy, on the other, we are now in a position to better appreciate the more fundamental, and quite profound, relationship between life and love, or grace and mercy. Before continuing, it should be pointed out that, due to the extremely close relationship that each of these has to/with the other, it’s fairly easy to jumble them together and sort of see them as synonyms for each other. This is especially the case when comparing grace and mercy as, not infrequently, spiritual writers and speakers will use the phrases “order of grace” and/or “order of mercy,” as though one could readily be substituted for the other.

In truth, the relationship of love to life, of mercy to grace, is this: Just as love, in its fruitfulness, is always fecund and invariably leads to new life, so too does the greatness of God’s mercy, which is the penultimate manifestation of his love, result in God’s stupendous gift of grace to humanity, which is nothing short of our participation in his own divine, Trinitarian life, for all eternity; that is, the ability of seeing and gazing upon the infinitely beautiful Godhead “directly,” without the aid of the senses or the grey-matter of the brain, which knows only through “ideas.” This is the glorious “Beatific Vision,” which “eye has not seen, ear has not heard, nor has it so much as entered into the mind of man what God has in store for those who love him” (cf. 1 Cor 2:9).

Recent Comments