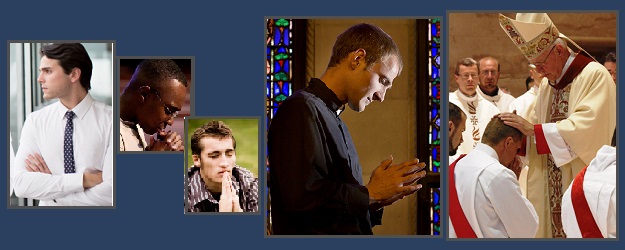

As Catholic seminaries across the country commence a new academic year and re-engage in the crucial work of priestly formation, so too a throng of young Catholic men—some finishing high school, some in college, some into the first years of a secular career—together, with not a few older Catholic men, will find themselves discerning the possibility that they are called to the priesthood. Vocational discernment is a delicate process. Aided and guided by God’s grace, and assisted by friends, family, spiritual directors and diocesan vocation directors, it will lead many of them to the seminary, possibly as early as a year from now.

If you are in the thick of that discernment process (or if you are trying to support someone who is), here are a few key questions about sexuality and emotional maturity (also referred to as affective maturity) that you should be asking yourself and discussing with your spiritual director and—in a lesser, yet sufficiently transparent degree of self-disclosure—with your diocesan or religious vocation director as well.

An affirmative answer to any one of these questions indicates an area that will require more careful attention and discernment on your part during pre-theology or college seminary (with the assistance of your spiritual director and formation advisor) and certainly prior to commencing major seminary. It could also be indicating that you do not have a vocation to the priesthood.

Are you considering the priesthood primarily because you feel drawn to “serve others”?

Such a motivation is laudable. And candidates to the priesthood had certainly better want to serve others. But if that is where the explanation begins and ends, then further examination of one’s motives is really required. Such can be the case, for example, with so-called “late vocations”—men who either never married or are widowers, who later in years see priesthood as a possible avenue for “service” in the Church (and this is often coupled with their own acute sense of the shortage of priests). Again, the motivation is laudable; but it is not enough in itself to demonstrate the presence of a genuine vocation to the priesthood.

The key question for a candidate to the priesthood is always this: Have you experienced a “call” from Christ? The word “vocation” itself derives from the Latin verb, vocare, “to call.” A “vocation” is a call, as in: “He went up the mountain and called to him those whom he wanted, and they came to him. And he appointed twelve, whom he also named apostles, to be with him, and to be sent out to proclaim the message” (Mk 3: 13-14).

The Church has always understood this Christ-originated calling as the primary motive for seeking ordination to the priesthood. This is why it is a matter of co-discernment: you, the candidate and those who represent the Church, engage in a process of discerning whether you have a genuine call to the priesthood. Sadly, it has always been possible, and remains so today, to pursue the priesthood for all the wrong reasons. Consequently, as stated in the Program of Priestly Formation (PPF) of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (5th edition):

Potential candidates for the priesthood must be in prayerful dialogue with God and with the Church in the discernment of their vocation. The linkage of this divine and ecclesial dialogue is especially important because “in the present context there is . . . a certain tendency to view the bond between human beings and God in an individualistic and self-centered way, as if God’s call reached the individual by a direct route, without in any way passing through the community” (Pastores dabo vobis, 37). Eventually, this dialogue, properly conducted, may bring candidates to the admissions process, completing this first phase of vocational discernment.1

The key to that co-discernment—between you, the candidate, and those who represent the Church—is to uncover motivations that transcend the mere humanitarian appeal of the Catholic priesthood (“serving others”). For the man called to the priesthood, there must be profound, rooted-in-the heart, motives, a whole interwoven set of them that form a core drive in one’s life, in addition to sound motivations like the desire to serve others. To name just a few:

- A love for the Eucharist;

- A longing to administer the sacraments to the people of God;

- A hunger to build up the Church, and promote bonds of profound ecclesial communion, especially in the dynamics of parish life;

- A drive to be a servant-leader and spiritual father to your brothers and sisters in the faith;

- A zeal to live to its ultimate consequences: a deep-rooted experience of Christic discipleship.

Granted, these motivations might only be incipient as you prepare to enter a college seminary program. But your ability to identify several of these motivations, and “connect the dots” between them, constitutes a considerable piece of evidence that your vocation is genuine.

Ultimately, your primal motivation should arise from your intimate friendship with Jesus Christ. Certainly by the time of your ordination, your seminary formators will want to hear from you a credible story about your personal encounter, once upon a time, with Jesus Christ, living and risen, who approached you on the shores of your life, and got into your boat, and whose divine person became irresistibly attractive. In the best case scenario, you will be able to share with them how you feel that a call to priesthood emanates from your love for Jesus Christ, how you want, like Jesus, to take on the Church as your bride, and serve her exclusively and unconditionally throughout the rest of your life.

It’s not enough for a candidate to the priesthood simply to “decide” that he wants to “serve others” as a priest; his heart has to be irrevocably set and fixated on Jesus from whom he has perceived an undeniable invitation and calling to follow him more intimately through priestly ordination.

Do you find the prospect of marriage and raising a family unattractive?

If so, then, “Houston, we’ve got a problem.” And if I may put it bluntly: if you do not find marriage and raising a family profoundly attractive—so much so, that at least now and then the struggle to forego them becomes something of a battle—then you really need to put on the brakes. Marriage is a “natural” vocation; there should be in every human heart a natural proclivity to human love, and to the procreation of new human lives through the bond of marriage. Without over-romanticizing it, and hopefully informing our understanding of marriage with loads of realism (diapers, arguments, money problems, in-laws, illnesses, and everything life can throw at a married couple)—married life should, nonetheless, always remain genuinely attractive to the celibate.

The priesthood is not for men who choose it as a default because of their own personality foibles that have made long-term relationships with women difficult or impossible. It is not for men who just don’t like kids, or who just prefer a bachelor’s life style. If you find marriage unattractive, if you cannot see yourself as a good husband and father, you really need to focus on discovering why that is. And that might even require some professional help.

Do you find emotional intimacy with others difficult or distasteful?

An affirmative answer here once again means you need to apply the brakes. We simply cannot underestimate the significance of one of the findings in the 2002 John Jay Report on the “Causes and Context of the Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests”: “Priests who sexually abused minors did not differ significantly from other priests on psychological or intelligence tests but had vulnerabilities, intimacy deficits, and an absence of close personal relationships before and during seminary.” I am not suggesting that any degree of discomfort with interpersonal relationships, or an inability to express and communicate emotion, might be indicating that an individual is a potential abuser. But the report does shed light on an immensely important, and for decades overlooked, element of preparation for priesthood: the seminarian’s (and eventually the priest’s) ability—even as a celibate—to be enriched by emotional communion with others in healthy and supportive friendships.

In truth, the priest cannot genuinely thrive in a commitment to celibate chastity without at least a few close and emotionally intimate friendships, male and female. Emotional intimacy is not sexual intimacy, and it certainly must be channeled within proper interpersonal boundaries. Nor is emotional intimacy to be confused with emotional dependency. Rather, we are talking here of a degree of interpersonal communion appropriate to the celibate state. It is, in a word, the most important manifestation of what we call “affective maturity.” As articulated in the PPF, affective maturity entails, among other elements, the following:

{A} deepening of the capacity to give and receive love, an ability to practice appropriate self-disclosure, an ability to develop and maintain healthy and inclusive peer friendships, and an ability to set appropriate boundaries by choosing not to act on romantic feelings, and by developing self-discipline in the face of temptation.2

It means an acquired degree of self-mastery over feelings and emotions which enables the celibate to be appropriately vulnerable, to manifest empathy, to communicate emotion with prudence and balance, and to share and receive appropriate gestures of affirmation and affection.

We want to see our candidates for Orders thriving in genuine friendships with men and women, single and married, and planning on being sustained in their priesthood by a close-knit network of such friendships.

Have you been unsuccessful at abstaining from sexual intimacies with women in your recent past? Do you frequently or habitually use internet pornography?

In most dioceses, it is expected that you will have not dated, and will have been able to remain serenely chaste, for at least a full year or more, prior to commencing college seminary, or a pre-theology program.

It will also be expected that any struggles with pornography of any sort will have been substantially overcome by the time you enter major seminary. Seminary is certainly an environment to grow in the virtue of chastity, to deal with relatively normal struggles in this area. But the seminary is definitely not the place to be struggling with unresolved and deep-seated sexual issues. Obsessive or compulsive behaviors have to be worked out prior to commencing seminary, most especially issues pertaining to internet pornography. A diagnosed addiction to pornography is normally an indication that a man is not suited for the priesthood.

Is your willingness to embrace the Church’s celibacy rule simply deferential and acquiescent? (“If I want to be ordained, I just have to accept it…”)? Are you hopeful that the rule will change under the current Pope or a future Pope?

Somewhere along the line, you really have to ask yourself if you have received a call to celibacy—a call that is in many ways distinct from the call to priesthood. At some point, you have to embrace serenely and resolutely what celibacy means: that you commit yourself—amidst the usual temptations and struggles—to strive in earnest for life-long abstinence from any deliberate sexual gratification. You certainly could not, in good conscience, begin any stage of seminary formation harboring and entertaining longings of sexual intimacy with others, leaving a door open to this for sometime down the road (whether during seminary, or after ordination). As well, along with all other persons, clergy and laity alike, who live outside of the bond of a valid marriage, you are called to pursue and live the virtue of chastity, and to embrace the Church’s teaching on all issues of sexual morality, including the very personal issue of masturbation.3

But beyond this, the seminarian should be able to discover the beauty in the celibate state. He should be able to discern within himself the God-given wherewithal to live in such a state. He should feel “at home” as he envisions himself living a chaste and celibate lifestyle, even in the company of married and single female friends. Indeed, celibacy would ideally be understood as a gift, and an avenue for an intense form of human flourishing. In other words, the candidate for Orders really needs to see celibacy as something eminently positive, compellingly attractive, and deeply, spiritually meaningful—as an expression of his love for Christ and the Church. Again to cite the PPF:

A candidate must be prepared to accept wholeheartedly the Church’s teaching on sexuality in its entirety, be determined to master all sexual temptations, be prepared to meet the challenge of living chastely in all friendships, and, finally, be resolved to fashion his sexual desires and passions in such a way that he is able to live a healthy, celibate lifestyle that expresses self-gift in faithful and life-giving love: being attentive to others, helping them reach their potential, not giving up, and investing all one’s energies in the service of the Kingdom of God.4

The man who is affectively mature habitually strives to invest his vital energies, pursuits, and endeavors in the spiritual and temporal good of the people of God, in their sanctification, and his own. He discovers early on in his discernment, in fact, that such a life can only be maintained by a habit of daily intimacy with Christ in prayer. Hence, a final paramount question.

Do you find in yourself little or no inclination to take time for daily personal prayer—beyond the recitation of formal prayers and devotions?

A sustained life of personal prayer is key to the development of affective maturity. Why? Because living in intimate union with God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—is “far more than a personal or individual relationship with the Lord; it is also a communion with the Church, which is his body.”5 Daily intimacy with Christ in personal prayer (whether understood as “mental prayer,” meditation, or lectio divina, whether in the privacy of one’s room, or before the Blessed Sacrament) will draw the candidate (and later, the priest) to a deeper desire for that transformative union with the Trinity to which we are all called. It will also draw that candidate into a deeper, affectively mature, and fruitful communion with the Church.

Here’s hoping that—before God and your own correctly formed conscience—you have been able to respond “no” to each of these questions. Either way, entrust your life, and your discernment, to Mary the Mother of Priests, and ask her to guide you along the path envisioned for you by God the Father from all eternity.

- Program of Priestly Formation §33. ↩

- Program of Priestly Formation §94. ↩

- That teaching is quite well summarized in the Catechism in these terms:

By masturbation is to be understood the deliberate stimulation of the genital organs in order to derive sexual pleasure. “Both the Magisterium of the Church, in the course of a constant tradition, and the moral sense of the faithful have been in no doubt, and have firmly maintained, that masturbation is an intrinsically and gravely disordered action.” “The deliberate use of the sexual faculty, for whatever reason, outside of marriage is essentially contrary to its purpose.” For here, sexual pleasure is sought outside of “the sexual relationship which is demanded by the moral order, and in which the total meaning of mutual self-giving and human procreation in the context of true love is achieved.” To form an equitable judgment about the subject’s moral responsibility, and to guide pastoral action, one must take into account the affective immaturity, force of acquired habit, conditions of anxiety, or other psychological or social factors that lessen, if not even reduce to a minimum, moral culpability (CCC §2352).

How deeply this runs counter to the common secular understanding of masturbation as a normal, wholesome, and in principle, morally neutral behavior cannot be exaggerated. The vast majority of lay Catholics—and a large portion of clergy and religious—for myriad reasons, have basically embraced that secular understanding, and become accustomed to living with a moral persuasion which they more or less know not to be in harmony with the Church’s moral tradition, just as they often do with regard to the Church’s teaching on contraception and homosexuality.

Some observations from the moral perspective are in order here given the broad denigration, rejection, or at least, misrepresentation of this teaching. To be sure, the Church teaches that masturbatory behavior—the stimulation of one’s own genitals for sexual pleasure, and the release of sexual tension—is what the Church refers to as “grave matter,” an objectively seriously disordered behavior. But to be considered a mortal sin, such behavior must be deliberate, that is, it must be a personal act, the result of a deliberate choice. They must be engaged in with a pondered understanding of their gravity (“full knowledge”) and by a willful choice (“full consent”). Lacking either or both of these latter two elements (due, for example to immaturity, or emotional duress, fatigue, semi-wakefulness and so on), the episode of masturbation in question does not constitute mortal sin, and is likely not even venially sinful.

Today, deliberate recourse to masturbation, with sexual fantasizing enhanced by internet pornography, can constitute a dehumanizing and destructive psychological cocktail whose devastating impact on relationships and marriages we are only beginning to assess.

It is certainly possible, however—contrary to common secular mischaracterizations—for celibates and non-celibates alike to strive to habitually forego deliberate masturbation without experiencing psychological duress, scrupulosity, “suppression” of urges, and so on. The Church has long fostered forms of healthy asceticism that sustain the pursuit of personal chastity by various means, everything from rigorous physical exercise, to healthy friendships, pastimes, and amusements, to a healthy mental hygiene that seeks interior freedom from our sex-saturated cultural media. Such a way of life is possible with God’s grace—particularly for the celibate. It is certainly possible to live a flourishing human life while striving to embrace every element of the Catholic Church’s teaching on human sexuality. ↩

- Program of Priestly Formation §94. ↩

- Program of Priestly Formation §108. ↩

I want to look a little more closely at the proposition that marriage is a “natural” vocation, and that there should be in every human heart a natural proclivity to human love, and to the procreation of new human lives through the bond of marriage, and that married life should, nonetheless, always remain genuinely attractive to the celibate.

All other things being equal, and in an ideal world, this is so. But many people, myself included, are not cut out for marriage. Circumstances – particularly economic ones – can dictate that a man not aspire to fatherhood, and even that it would be sinful for him to make himself available for marriage. This could be because he doesn’t have what it takes to be a father and has no faculty whatsoever for winning the heart of a woman. Don’t forget that a woman evaluates a man in terms of his suitability to be the father of her children.

None of your points, M, counter the idea that marriage is a natural vocation.

I would add, from personal experience, that if God is causing you to run into lots of physically failing, or morally failed priests, then that may be a sign to you that maybe you shouldn’t seek to be a priest.

“Emotional Intimacy”………..heh. I remember many years ago the vocations director at a supposedly laudable diocese in the center of the country required that all seminarians and prospects greet him with a full body hug. How intimate indeed! Perhaps I wasn’t “giving” enough, or his secret emotional detector told him that I was perhaps too “rigid” in giving of myself in this way, physically. Unlike a military recruiter, who finds the guys minimally qualified for military service and lets the boot camp formation make the soldier, this Vocations Director had the sole power to reject any candidate. How many vocations did he derail because of his perceived lack of “emotional intimacy”?

Abusus non tollit usum.