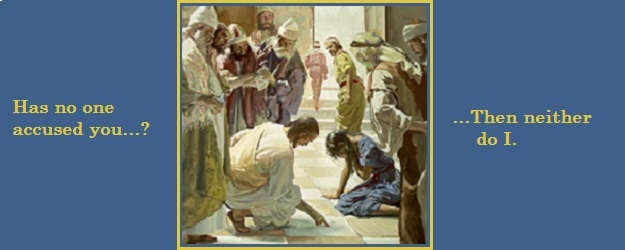

Jesus and the Woman Adulterer by Harry Anderson

Recently, Pope Francis, like so many of his predecessors in the Chair of St. Peter, has emphasized God’s special predilection for sinners. Indeed, not on one occasion only, but on many occasions, our Pontiff has taken great pains to make the fact of God’s particular love for sinners abundantly clear, as for example when he said that “the ability to acknowledge our own sins, to acknowledge our misery, to acknowledge what we are and what we are capable of doing or have done, is the very door that opens us to the Lord’s caress, His forgiveness.”1

On another occasion, he said, “Only one who has been caressed by the tenderness of mercy truly knows the Lord. The privileged place of encounter is the caress of Jesus’ mercy regarding my sin. This is why you may have heard me say, several times, that the place for this, the privileged place of the encounter with Jesus Christ, is my sin.”2 It is precisely this acknowledgement of personal sin, this caress and encounter, which are exemplified by the woman, Mary Magdalene, who washed Christ’s feet with her tears, and caressed and dried them with her hair.3 And it is precisely the self-emptying and self-accusing humility of this woman that the Pope has contrasted on numerous occasions to the self-referential and self-congratulatory pride of the Pharisees, one of whom was Jesus’ host when the woman approached him. The Pope observed that this Pharisee “cannot understand the simple gesture [of Mary Magdalene]: the simple gestures of the people. Perhaps this man had forgotten how to caress a baby, how to console a grandmother.”4 Significantly, Jesus does not rebuke the Pharisee in a harsh way for his lack of understanding, but rather He gently explains the woman’s actions to him by means of the following parable: “Two people owed money to a certain moneylender. One owed him five hundred denarii, and the other fifty. Neither of them had the money to pay him back, so he forgave the debts of both. Now which of them will love him more?” Simon replied, “I suppose the one who had the bigger debt forgiven.” “You have judged correctly,” Jesus said.5 Thus, Jesus in His own words seems to tell us that the one who has sinned more, and subsequently been forgiven by the Heavenly Father, like the prodigal son,6 will of necessity love God more than the one who, like the elder brother, has sinned less, and so has less need of the Father’s forgiveness. “Wherefore I say to thee: Many sins are forgiven her, because she hath loved much. But to whom less is forgiven, he loveth less.”7

This familiar and beautiful passage of Scripture has enormous implications for us, and for the whole Church. It means, quite simply, that we have cause for hope, for who among us is without sin?8 Who among us does not long to hear the words of Christ, our Judge, addressed to Satan, very likely even as he lays his hands on us to drag us down to hell: “Leave her alone!9 Many sins are forgiven her, because she has loved much!”10 It is precisely on account of this hope that the Church cries out in exultation, “O felix culpa! O happy fault!”11 In the words of Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet:12

There is nothing more touching in the Gospel than the way God treats his reconciled enemies—that is, converted sinners. He is not content to wipe away the stain of their sins. It is easy for his infinite goodness to prevent our sins from hurting us; he also wants them to profit us. He brings forth so much good from them that we are constrained to bless our faults and to cry out with the Church, “O happy fault! O felix culpa!” His graces struggle against our sins for the mastery, and it pleases him, as St. Paul said, that his “grace abound” in excess of our malice (cf. Rom. 5:20).13

If we meditate on this truth of our Faith with complete honesty for very long, however, we must admit a seemingly unresolvable paradox. If God is pure Goodness, how can He prefer sin to preserved innocence? One may reply that “God hates the sin, but loves the sinner,” just as we are called to do in His image. However, this does not solve the difficulty, because one could still point out that the existence of “the sinner” presupposes “the sin” that has already been committed, and if God actually preferred that we would be sinners (so that we could love Him more), then it would necessarily follow that He would prefer that we sin, rather than preserve our innocence. Strange, and almost blasphemous, as this may seem, it is a tremendously important and recurrent topic of theological discussion, particularly within the Protestant denominations of Christianity. This very question, and the answer provided by Martin Luther,14 is arguably, for better or for worse, the basis of Protestantism. One must not deny that there is much at stake in the answer to this question. Is it possible that God has “set us up” to sin, without any possibility of retaining the purity of soul that we had at the moment of our baptism, just so that He could make our sins profit us by forgiving them, by making us love Him more than we would have if we had not sinned? Luther pondered this question, and he insisted (naïvely) on the following answer:

Here, then, is something fundamentally necessary and salutary for a Christian, to know that God foreknows nothing contingently, but that he foresees, and purposes, and does all things by His immutable, eternal, and infallible will. Here is a thunderbolt by which free choice is completely prostrated and shattered. … From this it follows irrefutably that everything we do, everything that happens, even if it seems to us to happen mutably and contingently, happens in fact nonetheless necessarily and immutably, if you have regard to the will of God. … This is the highest degree of faith, to believe Him merciful when He saves so few and damns so many, and to believe Him righteous when by His own will He makes us necessarily damnable, so that He seems, according to Erasmus, to delight in the torments of the wretched and to be worthy of hatred rather than of love.15

Here, Luther can perhaps be given credit for asking an honest question. His answer, however, that it is the highest degree of faith to believe at one and the same time that (1) God “saves so few and damns so many” necessarily by an arbitrary choice of His divine will, with no regard for their own freedom or ability to choose goodness over sin, or their own personal merit, and (2) God is worthy of love rather than hatred, seems more like lunacy than piety. For one thing, it makes a mockery of the familiar invocation of the Lord’s Prayer: “lead us not into temptation…”16 Indeed, with his view in mind, it is no surprise that Luther advised his disciples to “sin boldly”! What can be said in reply to this proposition of Luther’s? To answer Luther adequately, we must enter the theological realm of grace and merit, which is notoriously thorny and “dangerous” territory, as Fr. John Hardon affirms:

The theology of grace is not simple, as may be seen from the sequence of errors strewn along the path of the Church’s history. The complexity of the subject is due as much to its intrinsically mysterious character, since it deals with nothing less than the life of God shared by His creatures, as to our natural proneness to rationalize and explain everything in this-worldly terms. Yet a clear grasp of the basic principles is useful and may at times be indispensable, for directing oneself and others on the road to salvation. It is no coincidence that the great heresies on grace, like Pelagianism and Jansenism, had a profound influence on the morals and spiritual life of those who professed these errors; and that influence is still exerted centuries after the original aberrations arose.17

Despite the complexity of the theology of grace and merit, God has provided His One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church with the answer key: the Holy Mother of God. It is no coincidence that Mary has been called from time immemorial The Destroyer of All Heresies. It is also no coincidence that the so-called great heresies of grace, including Pelagianism, Jansenism, and Protestantism in general, are overwhelmingly hostile to the Marian doctrines and dogmas of the Catholic Church, especially the unique grace of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. According to the Pelagians, Mary’s Immaculate Conception is unnecessary, because they believe that human nature is untainted by original sin, and therefore able to obtain salvation by its own power, without the necessity of grace. According to the Jansenists, Mary’s Immaculate Conception is impossible (a “pious exaggeration” at best, or “Mariolotry” at worst), because they believe that human depravity is absolute and irrevocable after the fall, and therefore incompatible with any form of personal merit based on preserved innocence or freedom from sin. For the Catholic, Mary provides a strikingly simple—humble—answer regarding the question of God’s preference: Does God prefer the repentant sinner or the one who has never sinned? While this would be a moot question for most of us, the question takes on concrete meaning and importance in the person of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who, in the words of Pope Francis, “by unique privilege, was preserved from original sin from the very moment of her conception. Even living in a world marked by sin, she was not touched by it: Mary is our sister in suffering, but not in evil or in sin. Instead, evil was conquered in her even before deflowering her, because God had filled her with grace (cf. Lk 1:28). The Immaculate Conception signifies that Mary is the first one to be saved by the infinite mercy of the Father, which is the first fruit of salvation which God wills to give to every man and woman, in Christ. For this reason the Immaculate One has become the sublime icon of the divine mercy which conquered sin.”18 It is not possible to imagine that Jesus Christ could love any creature more than His sinless Mother, the Immaculate Virgin Mary, on whom Eternal Wisdom chose to bestow His unchangeable predilection before the creation of the world; and this is the complete answer to our question! Once again, in the words of Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet:

If this is the case, then should we say that repentant sinners are more worthy than those who have not sinned, or justice reestablished is preferable to innocence preserved? No, we must not doubt that innocence is always best. … Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is holiness itself, and although he is pleased to see at his feet the sinner who has returned to the path of righteousness, he nevertheless loves with a stronger love the innocent one who has never strayed. The innocent one approaches nearer to him and imitates him more perfectly, and so he honors him with a closer familiarity. However much beauty his eyes may see in the tears of a penitent, it can never equal the chaste attraction of an ever-faithful holiness. These are the sentiments of Jesus according to his divine nature, but he took on other ones for the love of us when he became our Savior. God prefers the innocent, but, let us rejoice: the merciful Savior came to seek out the guilty. He lives only for sinners, because it is to sinners that he was sent. … And so this good Doctor, as Son of God prefers the innocent, but as Savior seeks out the guilty. Here is the mystery illuminated by a holy and evangelical doctrine. It is full of consolation for sinners such as we are, but it also honors the holy and perpetual innocence of Mary.19

Indeed, not only does this holy and evangelical (and, if we may reiterate, simple, and eminently humble) doctrine honor the holy and perpetual innocence of Mary, it also provides the fundamental argument in support of the dogma of her Immaculate Conception, which was first stated by the Franciscan theologian Bl. John Duns Scotus in his famous disputation with the Dominican theologians at the University of Paris in 1306 (or 1307).20 In effect, there must be at least one perfect creature after the fall of Adam and Eve—with perfect innocence, perfectly redeemed from the moment of her creation—or else we must admit that Christ is not a perfect redeemer. This argument is essentially reiterated by Bossuet as follows:

For if it is true that the Son of God loves innocence so well, could it be that he would find none at all upon the earth? Shall he not have the satisfaction of seeing someone like unto himself, or who at least approaches his purity from afar? Must Jesus, the Innocent One, be always among sinners, without ever having the consolation of meeting an unstained soul? And who would that be, if not his holy Mother? Yes, let this merciful Savior, who has taken upon himself all of our guilt, spend his life running after sinners; let him go and seek them in every corner of Palestine; but let him find in his own home and under his own roof what will satisfy his eyes with the steady and lasting beauty of incorruptible holiness! … He chose Peter, Matthew, and Paul for us, but he chose Mary for himself. For us: “whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas … all are yours” (cf. 1 Cor. 3:22); for himself: “My beloved is mine,” and I am hers (cf. Song of Sol. 2:16). Those whom he called for others, he drew forth from sin, so that they might the better proclaim his mercy. His plan was to give hope to those souls beaten down by sin. Who could more effectively preach divine mercy than those who were themselves its illustrious examples? … Yet if he treated in this way those whom he called for the sake of us sinners, we must not think that he did the same for the dear creature, the extraordinary creature, the unique and privileged creature whom he made for himself, whom he chose to be his Mother. In his apostles and ministers, he brought about what would be most useful for the salvation of all, but in his holy Mother, he did what was sweetest, most glorious, and most satisfying for himself, and, consequently, he made Mary to be innocent. “My beloved is mine,” and I am hers. … We must not persuade ourselves that to distinguish Mary from Jesus we must take away her innocence and leave it to her Son alone. … To distinguish Mary from Jesus, there is no need to put sin into the mix. It suffices that her innocence be a weaker light. That light belongs to Jesus by right, but to Mary by privilege; to Jesus by nature, to Mary by grace and favor. We honor the source in Jesus, and in Mary a flowing forth from the source. … The innocence of Jesus is the life and salvation of sinners, and so the innocence of the Blessed Virgin serves to obtain pardon for sinners. Let us look upon this holy and innocent creature as the sure support for our misery and go and wash our sins in the bright light of her incorruptible purity.21

According to Bl. John Duns Scotus, “grace is the sole root of merit.”22 However, besides the conditions for merit (de condigno) that are intrinsic to the act (such as “goodness, righteousness, conformity with reason, intensity of charity, etc.”) and intrinsic to the person performing the act (such as the conditions that the person must be “in the state of pilgrimage” and in the state of sanctifying grace), Bl. John Duns Scotus adds, “I believe that there is one other condition, to be verified as actual in fact, namely, the acceptability of such merit to God: not only in virtue of that common acceptance, whereby God accepts every creature…, but in virtue of a special acceptance, which is the ordaining of this act by the divine will to eternal life, as condign merit worthy of reward.”23

The fact that merit depends on divine acceptance means essentially that merit, like grace, is not deterministic from our point of view as creatures, because merit, like grace, ultimately depends on the divine will—ergo, the demise of all forms of causal or natural determinism (such as Pelagianism). The divine will, however, is not arbitrary, because once He has chosen, God contracts certain “responsibilities” consistent with Who He Is, such as His “duty” to honor His Mother—ergo, the demise of all forms of “theistic” or supernatural determinism (such as Jansenism, Calvinism, and Lutheranism), as well as Gnosticism, and all its “practical” variants (such as nominalism and voluntarism). God cannot contradict Himself—and this is no limitation on His Omnipotence, but rather an expression of His Infinitude, or Limitlessness, since a contradiction is in fact a limitation—and so He cannot act in a way that is inconsistent with Who He Is. This fact is at the heart of the mystery of “why God has preferences,”24 which is spoken of at some length by St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the Doctor of the Little Way, at the beginning of her autobiography:

Before taking up my pen, I knelt before a statue of Mary (the one that has given so many proofs of the maternal preferences of heaven’s Queen for our family), and I begged her to guide my hand that it trace no line displeasing to her. Then opening the Holy Gospels my eyes fell on these words: “And going up a mountain, he called to him men of his own choosing, and they came to him” (St. Mark, chap. III, v. 13). This is the mystery of my vocation, my whole life, and especially the mystery of the privileges Jesus showered on my soul. He does not call those who are worthy but those whom He pleases or as St. Paul says: God will have mercy on whom he will have mercy, and he will show pity to whom he will show pity. So then there is question not of him who wills nor of him who runs, but of God showing mercy” (Ep. to the Rom., chap. IX, v. 15 and 16).25

In his monumental work, the Mariology of Blessed John Duns Scotus, Fr. Ruggero Rosini explains:

Once it is understood that merit depends upon divine acceptance, merit by its very nature is then intrinsically the same for everyone [that is, the term “merit” can be used univocally for everyone, though the degree of merit is not the same]: Christ, Mary and the just. The difference lies in its extension. Scotus explains this by the fact that merit, not consisting in the personal act alone, is in some way also constituted by the circumstances in which the person accomplishes the meritorious act; hence God, in accepting the act, also accepts the circumstances of the one who performs the meritorious work. … We saw that Christ merited for all [by His redemptive sacrifice on the Cross], Mary included; by virtue of His divine Person He was able to merit in an infinite manner. In Mary, of course, we do not have an infinite person; however, in her case there is a circumstance which intimately links her to the very Person of the Word; and it is her divine Maternity. And if one participates in Christ’s perfections according to one’s degree of closeness to Him, certainly nobody was nor ever shall be characterized by a more rigorous union with Christ Himself than Mary.26

It is precisely in her alliance with Christ that Mary is unique, chosen by Christ for Himself, set apart by eternal decree in the divine intention of God the Father before the creation of the world to be the Immaculate Mother of His Son; and at the same time it is precisely in her alliance with Christ that Mary is like us. Once again, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet eloquently explains:

Theology teaches us that the differences we see in things are a result of Divine Wisdom. As Wisdom establishes order in things, it must also bring about the differences without which there can be no order. … Thus, the Blessed Virgin was set apart, and in her separation she possesses something in common with all men and something all her own. To understand this, we must realize that we have been set apart from the rest of men and women because we belong to Jesus and have an alliance with him. But Jesus made two alliances with the Blessed Virgin: one as Savior and another as Son. The alliance with Jesus as Savior means that she must be set apart like the other faithful; the special alliance with Jesus as her Son means that she must be set apart in an extraordinary fashion. Divine Wisdom, in the beginning you separated the elements out of the original confusion; here too there is confusion to dispel. Here is the whole of guilty mankind from which one creature must be set apart so that she may become the mother of her Creator. If the other faithful are delivered from evil, she must be preserved from it. And how? By a special communication of the privileges of her Son. He is exempt from sin, and Mary must also be exempt. O Wisdom, you have set her apart from the other faithful, but do not mix her together with her Son, because she must be infinitely beneath Him. How shall we distinguish her from him, if they are both exempt from sin? Jesus was by nature, and Mary by grace; Jesus by right, and Mary by privilege and indulgence. See her thus set apart: “he who is mighty has done great things for me” (Luke 1:49).27

On a theological level, if one wishes to argue that God would prefer sin to innocence, even if the sin that He would prefer is only a “means to an end” to make us love Him more, then one has no choice but to postulate a change in the very essence of the eternal Godhead. Rather than the divine nature being goodness, pure and simple, the divine nature would need to include at least some admixture of sin or evil, even if this “evil” is understood only as a privation of the objective “goods” of beauty, truth, love, etc. That is, one would have no choice but to understand the words of St. Paul—“God made Him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in Him we might become the righteousness of God”28—to be taken in the literal sense, and to apply to the divinity of Christ as well as to His humanity. We know that Christ suffered in His humanity. Indeed, we know that Christ’s merit in His suffering was infinite, in virtue of His Infinite Person, which His human nature shares with His divine nature (two natures, one person). However, if we claim that Christ’s suffering extended beyond His human nature to His divine nature, then we are actually claiming that a contradiction exists in the eternal Triune Godhead: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. This is one of the basic tenets of the heresy called Patripassianism, since if the Son suffered with His divine nature as well as with His human nature, then it must follow that the Holy Spirit and the eternal Father (Patri-) suffered (passio) with Him. But there’s the rub: by definition, suffering is a privation of the objective goods of health and happiness, just as death is the privation of the objective good of life. Thus, in a formal sense, suffering is an evil. If one claims that the divine nature can admit any kind of suffering, then one must admit the existence of evil in God. This was effectively the position of Martin Luther, and it continues to hold an attraction, even among Catholic theologians of our own time (such as Karl Rahner). Anyone who has loved another person deeply knows what it means to “love the faults” of another person. This means that one sees in the beloved person (perhaps in his or her physical appearance or in his or her behavior) unique traits that one considers truly beautiful and desirable, despite the fact that others who do not love that person may consider the same traits ugly and undesirable. This in no way means that we love things in our beloved that are objectively unlovable or evil! Indeed, unless we are disordered or selfish in our desires (in which case we cannot speak of love) then those special traits that we see and love in our beloved, and that the world may call faults, are undoubtedly objectively lovable, since the world rarely appreciates what is truly beautiful. God, above all, sees and loves the true goodness in every person He has created—more so than any human lover could.

Perhaps, it is a misguided sort of romanticism, or a mistaken analogy between the true form of “loving the faults” of a person, which is really just another form of loving a person’s goodness, and a false notion of “loving the sin” of a person, that has led some theologians (ancient and modern) to try to force a love for sin on God, thereby embracing some form of Patripassianism. Be that as it may, it was for this reason that Bl. John Duns Scotus was reluctant to affirm that Christ’s suffering was infinite in itself, even though the merit of Christ’s suffering was infinite in value because of divine acceptance. Ultimately, what is at stake here is the distinction of the human will of Jesus Christ and the divine will of the Eternal Word, which are not identical. Indeed, the heresy of Monotheletism, which claims that the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ have only one shared will, was condemned in the Lateran Council of 649, which was summoned by Pope St. Martin I (d. 655) expressly to deal with this heresy. The summoning of this council was one of Pope St. Martin I’s first official acts as Pope, and it resulted in his almost immediate exile and martyrdom, since the heresy had the support of the reigning Byzantine emperor Constans II. The heresy of Monotheletism, which at first sight may seem of little consequence (though Pope St. Martin literally gave his life to fight against it), is a serious error, because if Jesus has no free human will of His own, then His temptations in the desert29 can only be considered “symbolic”; and if the Master’s confrontation with and victory over temptation was merely symbolic, then where does that leave the Master’s servant when he or she is faced with temptation, except in a state of utter despair and subsequent abandonment to sin? (Hence, Luther’s advice to his disciples to “sin boldly”.) Moreover, historically the heresy of Monotheletism leads quickly to another heresy, called Monophysitism, which claims that Jesus Christ has only one nature (divine), and not two natures (divine and human). This heresy was condemned in the Sixth Ecumenical Council in 680-681.

According to Bl. John Duns Scotus, divine acceptance is a manifestation of the divine will (free, but not arbitrary), and thus the ordering of the “relative infinities” of both Jesus and Mary, which include their glories, graces, and merits, is ultimately a manifestation of divine love. In the words of Fr. Peter Damian Fehlner:

The human love of Christ, all perfect and sinless: viz., maximal, nonetheless remains formally and objectively finite. To claim otherwise is to confuse the human will of Christ with the divine (monotheletism, ultimately leading to monophysitism and some form of patripassianism or suffering on the part of the divine nature to explain the redemptive sacrifice of Jesus, a position subsequently, effectively embraced by Luther and seemingly by Rahner in our times.30

It is by divine acceptance that Mary can merit grace with Christ, because of the unique intimacy of her union with Him. This Scotistic understanding of merit forms the theological foundation for the Catholic doctrine (not yet dogma) of Marian Coredemption with Christ. What may seem like an esoteric doctrine to Catholics who do not understand its importance, Marian Coredemption (which is necessarily related to Mary’s mediation of all graces) is actually a critical doctrine for a correct understanding of the God-Man Jesus Christ, in all His mystery and incarnate reality. Just as the Marian title “Theotókos” and the ascription of divine Maternity to Mary at the Council of Ephesus safeguarded the divine Personhood of Jesus Christ against the heresy of Nestorianism, which claims that the God-Man Jesus Christ and the Eternal Word are separate persons (or that Jesus Christ is two persons with two natures, rather than one person with two natures), so the Marian title “Coredemptrix” and the ascription of merit de condigno to the Blessed Virgin Mary in the work of the objective Redemption on the basis of personal sanctity and divine acceptance safeguard the human nature and free human will of Jesus Christ against the errors of Monophysitism and Monotheletism, which lead to the rejection of the possibility of merit for any human being, and consequently despair and abandonment of morality. In the words of Fr. Peter Damian Fehlner:

Either Mary is Mediatrix of all graces because She is Coredemptrix, or there is no fruitful mediation: magisterial, pastoral, sacramental, charismatic, by anyone in the Church. In rejecting the maternal mediation of Mary in the Church and her invocation (not merely her veneration) in time of trouble and the practice of true devotion to her, the Protestant reformation logically also rejected the mediation of the Church, in particular priestly-sacramental. With this, it becomes clear that the slogan [of Luther]: Christus solus is simply a modern western version of the ancient monophysitism and monotheletism: a radical denial of the very possibility of creaturely, free cooperation (merit and good works above all) in the work of redemption, beginning with the divine Maternity and effecting of the Incarnation. The mystery of Mary as Mediatrix, whether affirmed or denied, becomes the center of a controversy over grace and justification, faith and good works, above all over the mission of the Holy Spirit and of life in the Spirit in the realization of the plan of salvation. The reason is this: at the center of the working of the Spirit is the maternal mediation of the Virgin Mother.31

Stephen Ray insightfully likens the Marian doctrines of the Catholic Church to the moat around a castle: they are there to help define and defend the doctrines of Christ.32 Pope Benedict XVI (then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) goes even further:

Conversely: only when it touches Mary and becomes Mariology is Christology itself as radical as the faith of the Church requires. The appearance of a truly Marian awareness serves as the touchstone indicating whether or not the Christological substance is fully present. Nestorianism involves the fabrication of a Christology from which the nativity and the Mother are removed, a Christology without Mariological consequences. Precisely this operation, which surgically removes God so far from man that nativity and maternity—all of corporeality—remain in a different sphere, indicated unambiguously to the Christian consciousness that the discussion no longer concerned the Incarnation (becoming flesh), that the center of Christ’s mystery was endangered, if not already destroyed. Thus in Mariology Christology was defended. Far from belittling Christology, it signifies the comprehensive triumph of a confession of faith in Christ which has achieved authenticity.33

When discussing merit and grace, “safety” is found precisely in the arms of Our Mother, the Destroyer of All Heresies. Indeed, it is precisely by giving us His Mother as an example that God has provided us with an infallible “answer key” to the subtle problems of grace and merit, guiding the Barque of St. Peter with a sure rudder to the true “Catholic Middle-Ground” between “the two shoals of despairing of man’s native powers because of the fall, or ignoring original sin and so exalting human nature that nothing is supposed to be impossible to man.”34 Thus, while we rejoice ceaselessly that Christ came “not to call the righteous to repentance, but sinners,”35 we rejoice equally that it was the Holy Innocence of the Blessed Virgin Mary that pleased the Eye of the Thrice Holy Trinity, as does the same innocence in those who are most perfectly conformed to the pure image of the beloved Daughter, Spouse, and Mother of God. That is why, within the hagiography of the Catholic Church, for every penitent Augustine, there is a pure Agnes; for every convert Paul, there is a constant Pio. Great is Mary Magdalene, but infinitely greater is Mary, the Mother of God, and the Mother of us. For, in the words of Charles Péguy:

They say they’re full of experience; they gain from experience.

{D}ay by day they pile up their experience.

“Some treasure!” says God.

A treasure of emptiness and of dearth. …

A treasure of wrinkles and worries.

The treasure of the lean years. …

What you call experience, your experience, I call dissipation, diminishment, decrease, the loss of innocence.

It’s a perpetual degradation.

No, it is innocence that is full and experience that is empty.

It is innocence that wins and experience that loses.

It is innocence that is young and experience that is old.

It is innocence that increases and experience that decreases.

It is innocence that is born and experience that dies.

It is innocence that knows and experience that does not know.

It is the child who is full and the man who is empty.

Like an empty gourd, like an empty beer-barrel.

So, then, says God, that’s what I think of your “experience.” 36

- Pope Francis, Homily, Sept 18, 2014. ↩

- Pope Francis, Address to the Communion and Liberation Movement, March 7, 2015. ↩

- Cf. Luke 7:36-50, Matthew 26:6-13, Mark 14:3-9, John 11:2 and 12:3. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, “The Greek Fathers, as a whole, distinguish the three persons: the sinner of Luke 7:36-50; the sister of Martha and Lazarus, Luke 10:38-42 and John 11; and Mary Magdalene. On the other hand most of the Latins hold that these three were one and the same.” Indeed, St. John leaves us little choice but to identify the first two as one and the same woman, when he clearly tells us that “Bethany was the name of the village where Mary lived, with her sister Martha; and this Mary, whose brother Lazarus had now fallen sick, was the woman who anointed the Lord with ointment and wiped his feet with her hair.” (John 11:1-2) ↩

- Pope Francis, Homily, Sept 18, 2014. ↩

- Luke 7:41-43. ↩

- Luke 15:11-32. ↩

- Luke 7:47. ↩

- Cf. John 8:7. ↩

- John 12:7. ↩

- Luke 7:47. ↩

- From the Exultet, or Easter Proclamation, sung at the Easter Vigil Mass. ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (d. 1704) was a French bishop and theologian. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Bossuet was one of the greatest orators of all time, “the greatest, perhaps, who has ever appeared in the Christian pulpit—greater than Chrysostom and greater than Augustine; the only man whose name can be compared in eloquence with those of Cicero and of Demosthenes (1617-70).” ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Meditations on Mary, edited and translated by Christopher Blum, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2015, p. 23. ↩

- Martin Luther (d. 1546) initiated the Protestant reformation with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517. ↩

- Martin Luther, On the Bondage of the Will, from Luther’s Works vol. 33, pp. 37-63. ↩

- Matthew 6:13. ↩

- John Hardon, SJ, History and Theology of Grace, Sapientia Press, Ave Maria, FL, 2002, pp. xiii-xiv. ↩

- Pope Francis, Angelus for the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Dec 8, 2015. ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Meditations on Mary, edited and translated by Christopher Blum, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2015, pp. 24-25. ↩

- Cf. Stefano Manelli, FI, Blessed John Duns Scotus: Marian Doctor, Academy of the Immaculate, New Bedford, MA, 2011. ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Meditations on Mary, edited and translated by Christopher Blum, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2015, pp. 25-27. ↩

- Ruggero Rosini, OFM, Mariology of Blessed John Duns Scotus, translated by Peter Damian Fehlner, FI, Academy of the Immaculate, New Bedford, MA, 2008, p. 173. ↩

- Bl. John Duns Scotus, Ordinatio, I, d. 17, pars 1, q. 1-2, n. 129, in ibid., p. 167, footnote 77. ↩

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Story of a Soul, Third Edition, Translated from the Original Manuscripts by John Clarke, OCD, ICS Publications, Washington, DC, 1996, p. 13. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ruggero Rosini, OFM, Mariology of Blessed John Duns Scotus, translated by Peter Damian Fehlner, FI, Academy of the Immaculate, New Bedford, MA, 2008, pp. 173-175. ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Meditations on Mary, edited and translated by Christopher Blum, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2015, pp. 12-14. ↩

- 2 Corinthians 5:21. ↩

- Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Meditations on Mary, edited and translated by Christopher Blum, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH, 2015, pp. 24-25. ↩

- Peter Damian Fehlner, FI, “Coredemption and the Assumption in the Franciscan School of Mariology: The ‘Franciscan Thesis’ as Key” in Mariological Studies in Honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe—I, Academy of the Immaculate, New Bedford, MA, 2013, p. 207. ↩

- Peter Damian Fehlner, FI, “Opening Address” in Mary at the Foot of the Cross—VII: Coredemptrix, therefore Mediatrix of All Graces. Acts of the Seventh International Symposium on Marian Coredemption, Academy of the Immaculate, New Bedford, MA, 2008, p. 3. ↩

- Cf. Stephen Ray, “Mary, the Mother of God” in The Footprints of God video documentary series, Ignatius Press, Ft. Collins, CO, 2003. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI (then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger), Daughter Zion: Meditations on the Church’s Marian Belief, translated by John McDermott, SJ, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, CA, 1983, pp. 35-36. ↩

- John Hardon, SJ, History and Theology of Grace, Sapientia Press, Ave Maria, FL, 2002, p. 76. ↩

- Luke 5:32. ↩

- Charles Péguy, “Le Mystère des Saints Innocents” in Oeuvres poétiques complètes, Paris, 1957, p. 787f, as quoted by John Saward, The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty: Art, Sanctity, and the Truth of Catholicism, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, CA, 1997, p. 83. ↩

Recent Comments