There is a story of a landowner who went out early in the morning to hire workers for his vineyard. He agreed to pay them a denarius for the day and sent them into his vineyard. About nine in the morning he went out and saw others standing in the marketplace doing nothing. He told them,”You also go and work in my vineyard, and I will pay you whatever is right.” So they went. He went out again about noon and about three in the afternoon and did the same thing.

In my story, he went out again at about five in the afternoon and found still others standing around: all of them women. He asked them, “Why have you been standing here all day long doing nothing?” “Because no one has hired us,” they answered. He said to them, “You also go and work in my vineyard.” So they went into the vineyard but they found that all the best jobs had already been taken, and so the foreman merely put them to work cleaning, holding coffee mornings for worthy charities, and embroidering kneelers.

So runs the gospel according to the frustrated catholic woman who feeling like she is, to borrow a phrase from the corporate world, knocking her head up against a stain glass ceiling.

While this is, ultimately, a wrongful articulation of the situation, it must have some truth to it because Pope Francis has expressed his “vivid hope” that women will play a “more capillary and incisive” role in the Church as well as in all the places in which “the most important decisions are adopted.”1 In his Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, he called for a “more inclusive female presence in the Church.”2 The Pope certainly sees room for growth here.

But, what would such a presence look like? And, moreover, what principles do we have to guide this discussion of a greater presence? Since, aside from my wife and four daughters, women are something of a mystery to me. In exploring this, I shall lean heavily upon someone else who seemed to be much better acquainted. In Christifidelis Laici, John Paul II points the way forward by placing before us two principles:3

First Principle: Threefold Office

The first principle is that an ecclesial mission is necessarily more than permission: it requires spiritual empowerment. This is because the Church is a supernatural society with a supernatural undertaking. Our natural powers and talents are insufficient. Yet, unlike Prometheus, we cannot simply go up and steal the fire from the gods. Rather, we must wait “to be clothed with power from on high” (Luke 24:29). This is to say, that we must go to where the power is conferred, and this happens primarily in the character sacraments. For women, this means that it happens in baptism and in confirmation. But, baptismal character not only empowers, it also gives the recipient a share in Christ’s threefold office of priest, prophet, and king. This is symbolized by the baptismal anointing with oil, since in the Old Testament only priests, prophets, and kings were anointed. The point here is that the feminine ecclesial vocation will in some way orbit around this threefold office.

Second Principle: Threefold Motherhood

The second principle to guide our discussions is that, if we are interested specifically in the ecclesial vocation of women, then this is going to have to factor in that which is unique about women, namely their capacity for motherhood. Hence, the distinctively feminine vocation in the Church is going to factor in this reality. This can be taken in three ways. There is physical motherhood, there is motherhood of the spiritual order (found particularly in consecrated virginity), and there is what might be called transcendental motherhood. I call this last one “transcendental” because it transcends the different states of life. It pertains to wives and mothers, to consecrate virgins, and to those in neither category. This last type of motherhood is what is meant by the phrase “the genius of woman.”

While not synonymous with IQ, this “genius” is a kind of intelligence, if we take intelligence to mean the ability to ‘”read inwardly,” which seems to be the etymology of the word. It is, then, the ability to read inwardly the truth of the human person. It is variously described by John Paul II as the ability to see the value of the person, to place the person at the center of considerations, attunement, or sensitivity to what is authentically human, and capacity for the other.4

To get a handle on this, compare for a moment the fifth and sixth Stations of the Cross. Compare Simon and Veronica. Both come to the aid of Christ, but one has the sense that, for Simon, the help is the fulfillment of a task, perhaps unwillingly accepted at first (though clearly later embraced). Veronica’s encounter with Christ, on the other hand, is personal, through-and-through. With her feminine genius, she is able to penetrate through the horror of the situation to the personal core of the drama. She is, one might say, able to put the person at the center of the canvas.

This feminine talent is closely linked to a woman’s physiological aptitude for motherhood. A woman has a physical capacity for another person (for a child) and this physical capacity has a spiritual and psychological resonance.5 John Paul II says:

This unique contact, with the new human being developing within her, gives rise to an attitude towards human beings, not only towards her own child, but every human being, which profoundly marks the woman’s personality.6

It is very important to note that this aptitude does not depend on the woman actually being a mother in the physical realm. It is more the kind of being that she is (rather than any action) that confers upon the woman this “genius.” It is also important to note that the values that are highlighted by the genius of women are common to both men and women alike; it is only that women have a special sensitivity to these values.7 In this sense, the genius of woman is like the charism of a religious order. Indeed, in the Way of the Cross, we see the sensitivity to the person manifest in the male figures of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea in how they care of the body of Christ. Still it is Veronica that blazes the trail.

The Thesis

Having now laid out the two principles, the thesis should be clear. The ecclesial vocation of a woman is determined by her consecration through baptism and confirmation as king, prophet, and priest. She will express this threefold office in a specifically feminine vein. This mode of living the threefold office will be marked by motherhood that is physical, spiritual, or transcendental. I shall now attempt to sketch the outline of the ecclesial mission of women in light of this thesis.

The Kingly Office

The essence of the kingly office is to win the world for Christ the King: “Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” This implies two things: evangelization, and seeking to bring the temporal order under the rule of Christ.

Consider the following quote from Paul VI’s Evangelii Nuntiandi, issued ten years after the close of Vatican II:

Lay people, whose particular vocation places them in the midst of the world, and in charge of the most varied temporal tasks, must, for this very reason, exercise a very special form of evangelization. Their primary and immediate task is not to establish and develop the ecclesial community—this is the specific role of the pastors—but to put to use every Christian and evangelical possibility latent but already present and active in the affairs of the world.8

That the task of the laity is not “to establish and develop the ecclesial community” jars somewhat with the experience of the last fifty years because since the close of the Council, there has been a waxing of lay activity in the Church with a corresponding waning of Catholic penetration into the culture. There has been an upturn of what we might call lay ecclesial ministry, and a downturn in the lay apostolate. Lay ecclesial ministry is activity by lay persons inside the Church, both part-time (lectors, extra-ordinary ministers of the Eucharist, etc.) and full-time (directors of religious education, youth ministers, etc.) where the layperson acts as an extension of the hierarchy. Lay apostolate is activity outside of the formal structures of the Church, and not as an extension of the hierarchy, such as: parents raising their children in the faith, personal witness, and evangelization, pro-life activism, catholic workers groups, and so on. 9 The former is, effectively, work for the Bishop (often passing through the local pastor), whereas the latter is activity with the Bishop in the sense that it shares in the work that the Bishop has ultimate responsibility for, and it is “commissioned” by the Bishop on account of a connection that a lay person has to him via the Sacrament of Baptism, Confirmation, or Matrimony. Yet, it is carried out with significant autonomy.

Several things have contributed to this new situation. Among these are: a “shortage” of priests, a weakening in evangelical zeal—perhaps as a result of a misconception about the salvific value of other religions—and a misunderstanding of the extent to which culture ought to be penetrated by the Gospel. This situation has, according to John Paul II, led to two temptations on the part of the laity:

…{T}he temptation of being so strongly interested in Church services and tasks that some fail to become actively engaged in their responsibilities in the professional, social, cultural, and political world; and the temptation of legitimizing the unwarranted separation of faith from life, that is, a separation of the Gospel’s acceptance from the actual living of the Gospel in various situations in the world.10

The point is that lay ecclesial ministry is not the normal way for a lay person to fulfill his or her ecclesial vocation. Professional lay ministry is exceptional, and the voluntary lay ministry is like a hobby, compared to the lay apostolate which is like a job. The bread and butter of the lay ecclesial mission will always be out there in the world: it is the lay apostolate. I think a slight shift in focus here would somewhat lance the boil of frustration that many lay persons, and particularly women, feel in terms of the limited opportunities for exercising their undeniable talents inside the Church.

Feminine Genius and the Kingly Office

Everything I have said so far about the kingly office applies to men and to women indifferently. What, then, could be the specifically feminine contribution as regards conformity of the temporal order to the Gospel and evangelization?

Conforming of the Temporal Order

The first and most decisive contribution of women to society is via the home. After all, the family is the cell of society, and a body is as healthy as its cells. The American poet William Ross Wallace famously said that “the hand that rocks the cradle, is the hand that rules the world.” This is at once very helpful and potentially misleading. It is helpful because it reminds us that the future of humanity passes by way of the mother. And yet, it could be misleading because it only mentions the cradle. This perhaps masks the true extent of the task. The mission set before the mother is to create, in her own home, precisely that culture which we would wish to see in the whole of society. It is that task of creating Christendom: a culture penetrated, through and through, with the Gospel, and where Christ reigns supreme. At this time, in terms of the future of our society and of the Church, I very much doubt that there is a more important ecclesial mission.

Of course, this task is collaborative, it demands that the mother and father work together. Complementarity and cooperation (rather than interchangeability and antagonism) are the hermeneutics to follow here. And, yet, this task does fall in a special way to the woman, to the mother. After all, her womb is the first home of the child, and the physical home is always, somehow, an extension of this. The children were in her, and so she is somehow more in the children than the father, and this gives to her a privileged access to the hearts of her children. And in nurturing, to borrow a phrase from Cardinal Newman, “heart speaks to heart.”

While the feminine contribution to winning the culture for Christ begins in the home, it by no means ends there. Rather, the genius of woman asks that, if a woman does leave the home to go out into either the market place or the public square, she would bring the home with her. She is called to be a snail! By this is meant that she needs to bring the humanizing influence of the genius of woman into the world that she enters. Modern economic and political life is feral, and it needs to be domesticated. John Paul II speaks of the feminine genius as needed for “the establishment of economic and political structures ever more worthy of humanity.”11

Hans Urs von Balthasar noted that western culture is no longer patriarchal (how could it be when so many children live without fathers) but it is still “a man’s world” in the sense that it is a technological culture, obsessed with the domination of nature for the sake of private gain. To be more precise it is a fallen man’s world.12 The male genius (there is such a thing) has to do with subduing creation for the common good.13 The fallen male genius perverts this, and pursues a self-serving domination. The feminine genius is needed to put the person (and the family), rather than profit, back at the center of the economy.

The industrial revolution severed the family from the economy. Formerly, the family was the locus of economic life. The economy served the family and conformed it to its needs. Now the family is asked to dance to the beat of the economy. Women need to demand the right to participate in the economic life of nations while keeping the fundamental connection to motherhood. That is, without deny that work which is most specially theirs.14 Only then will the family be placed back at the center. But, if they enter the workforce simply as neuter or male surrogates, nothing will change.

In the public square, John Paul II sees the feminine genius as bringing peace and conciliation. Speaking of the “rings,” Galadriel tells us that: “Three were given to the Elves; immortal, wisest and fairest of all beings. Seven, to the Dwarf Lords, great miners and craftsmen of the mountain halls. Nine rings were given to the race of men, who above all seek power.” Here, for race of men, we should read males. My own children have Lord of the Rings “Top Trumps” playing cards, and I have noticed that the female characters always score low on “Ferocity” and high on “Resistance to the Ring.” As Mary Eberstadt points out, women are a corrective to a male temptation to assert themselves over others in the pursuit of power.15 Turf-wars aren’t a woman’s cup of tea (or poison), so to speak. A female presence often allows men to work together without indulging this felt need for constant self-assertion. We know from the Gospels, that even the apostles had moments where this male foible rose to the surface (Luke 9:46). One might speculate perhaps that Jesus purposefully included women among his inner group of followers (Salome, Joanna, Mary of Clopas, and so on), precisely on account of their soothing effect.

This calming influence can be connected with what Pius XI calls the woman’s “primacy in the order of love.”16 By that, he doesn’t mean that women are necessarily more loving than men, but rather that they evoke love in men: they jump-start the love process, as we see with Adam’s outburst at the creation of Eve (Gen 2:23). In this way, women are a remedy to a male hardness of heart.

The Feminine Genius and Evangelization

We have seen that the kingly office is about infusing the temporal order with Christian values. It is also about evangelization. We are light, as well as leaven.

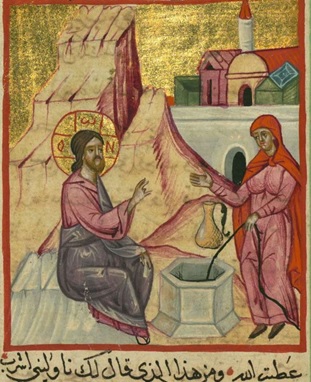

In matters of evangelization, the feminine genius teaches us two things: that evangelization flows from a personal encounter with Christ, and that it consists in a personal invitation to the one being evangelized. The “Woman at the Well” is the first evangelist recorded in John’s Gospel, and she sets the pattern. 17 First, she has a profound and life-changing encounter with Christ. Several things point to this. For one, when she rushes back to town to tell of her encounter, she leaves the water jars at the well, since now she is drinking from another Source. And again, after her five husbands, and the man she now lives with, (the six men are symbolized in iconography by a hexagonal well), Christ is her seventh, and perfect bridegroom: a nuptial union of the spiritual order has been established. Remember, the encounter takes place at Jacob’s Well, and Jacob met his spouse, Rachel, at a well.

Having encountered Christ, the woman draws others into this experience with the simplest of personal invitations: “come see the man who told me everything I ever did” (John 4:29). None of this is to disparage programs and techniques, but the feminine genius reminds us of the heart of the New Evangelization … it’s person-by-person, at a personal level.

The Priestly Office

In speaking about the confluence of the feminine genius and the priestly office, we must first of all carefully distinguish the common priesthood from the ministerial priesthood. The common priesthood is about utilizing mundane realities which are raw material for spiritual sacrifices. The ministerial priesthood is about being able to act in the person of Christ so as to confect the Eucharist, and to forgive sins by sacramental absolution.

God made two decisions that ultimately exclude a woman from the ministerial priesthood. The first decision was to assign to sexual distinction a privileged place in revelation: a fact verified by even a cursory reading of the Old Testament. The second decision was to empower the Christian priest to act in the person of Christ. That he does so is clear from the Mass where the priest speaks in the very person of Christ saying, “This is My Body.” Taken together, this means that Christ came as the Bridegroom, and that the priest acts in the person of Christ, the Bridegroom. This is a theological basis for the reservation of the ministerial priesthood to men alone.

And Christ made a third choice. He chose to unite sacramental power with juridical power. Hence, it was to the very same men that he said “do this in memory of me” (Luke 22:19) that he also said “whatsoever you bind will be bound” (Matt 18:18). This third choice was to ensure that the exercise of authority in the Church would always be for the same end as the purpose of the sacraments themselves, namely sanctification. Yet, there can be no doubt that this does exclude women, along with all lay-men, from positions of ultimate authority in the Church: positions that require the power to legislate and to judge. Of course, this exclusion is not rational, since women have all the human skills to be good pastors but, then again, the Church is not a rationally, but a super-rationally, constituted society.

Yet, there remains open a wide scope of participation in the mission of the Church (with significant authority) in roles that do not demand ordination. These might include being the President of a Pontifical Council, the Rector of a Pontifical University, or a peritus at an Ecumenical Council or Synod. Certainly, whatever is open to the lay man is, potentially, open to a lay woman. Furthermore, the reawakening of the charismatic dimension of the Church from centuries of hibernation has opened up new vistas of opportunities for lay persons (men and women). This is because the charismatic dimension, unlike the sacramental, is not tied so closely to the juridical order. Women have taken a leading role in this second spring, especially in some of the new communities. One could point to Chiara Lubich (Focolare) and Carmen Hernandez (Neocatechumenal Way), as well as Marthe Robin (Foyer de Charité). The current head of that body, which represents the charismatic renewal to the Holy See, is also a woman (Michelle Moran).

Lastly, we need to remember that not all authority is formal. There is, also, what might be called prophetic authority. Often prophetic authority can only be exercised by those who are excluded from the formal authority structures: they are outsiders who do not need to worry about things like “cabinet responsibility’.” This type of dual leadership seems to have been God’s plan for Israel during the period of the Kings. There was David and Nathan, Ahab and Elijah, Hezekiah and Isaiah. If I were asked who had exercised the greatest authority in the Church over the last three decades, I would be inclined to consider a king and a prophet, a man and a woman. Two saints: John Paul II and Mother Teresa.

Anyhow, arguments about authority and power in the Church are, at the end of the day, always a little shameful. Christ and His Church are on the way to Calvary again in our own day, and we, like the apostles, are arguing about who is the greatest, and who should have the seats of power to the right and to the left.

Motherhood and the Priesthood: Sanctifying the Mundane

Women are, then, excluded from the ministerial priesthood, but they have several unique ways to exercise the common priesthood: in particular, by way of natural motherhood, and consecrated virginity.18

We have seen that the common priesthood is about using day-to-day realities as the raw material for spiritual sacrifices: sanctifying and elevating the mundane in a way analogous to what the priest does to the bread at Mass. Mothers have a lot of raw material. Without stepping out of her front door, she has the whole range of the corporate and spiritual works of mercy before her: feed the hungry; give drink to the thirsty; clothe the naked; harbor the harborless; visit the sick. Even bury the dead—since few couples have not lost a child either in utero or in infancy. And then there are the spiritual works: to instruct the ignorant (and, here, remember she has a husband as well as a child); counsel the doubtful; admonish sinners; bear wrongs patiently; forgive offences willingly; and so on. Pope Francis has suggested that, in this Year of Mercy, we might all seek to do one corporeal, and one spiritual, work of mercy a day. It seems to me that the average mother does one every five minutes. It is often said that the “devil is in the details.” How untrue! The Lord is in the details, and so is, for the most part, the ecclesial vocation of the lay person.

And all of this is after giving birth. Perhaps the best line in the entire Scripture for understanding the common priesthood comes from St. Paul’s letter to the Romans, when he says, “Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship” (Rom 12:1). Every woman who has given birth, and who has nursed a child, knows what St. Paul means here by offering one’s body as a living sacrifice. Motherhood is a unique response to this appeal, perhaps surpassed only by martyrdom. The stretch marks and the caesarean scars: these are a mother’s battle scars, and I suspect that at the resurrection of the body (despite the application of anti-wrinkle cream) God will not take them from the body but will glorify them, just as, according to Aquinas, Christ’s nail marks (the sign of His priesthood) are not absent from the His resurrected body but are luminous as signs of His great sacrifice of love.19

All this, again, challenges us to make a paradigm shift from, thinking of our ecclesial mission as something exercised in the formal structures of the Church, to something that takes place as a response to our life in the world.

Supernatural Motherhood and the Priesthood: Mediation

Just as physical motherhood gives to a woman a unique way to live out the common priesthood, so also does the consecrated life (or motherhood in the spiritual order). An essential characteristic of the priest is that he is a mediator. The ministerial priest mediates divine life to us principally through the instrumentality of the Sacraments. It is on account of this spiritual begetting that we call the priest “father.” The consecrated woman also mediates grace; not by means of the sacraments, but on account of her spiritual communion with Christ. She makes herself wholly available to Her Spouse, becomes fruitful in the realm of the spirit and, thereby, begets spiritual children. That is why we call her “mother.”20

This reminds us of an important truth about ecclesial ministry, namely that, before we are called to be workers in the vineyard, we are called to be part of the vine itself, and that our productivity as workers is proportioned to our union with this Vine: “I am the vine; you are the branches. If you remain in me, and I in you, you will bear much fruit; apart from me, you can do nothing” (John 15:5). This principle of our ecclesial vocation is taught in a singular fashion by the icon of the Theotokos of the Sign—Mary is pictured with Christ inside of her. She simply raises her arms up to heaven, while it is Christ, in her womb, who blesses with one hand, and teaches with the other.

The Prophetic Office

Among the many ways in which women are prophetic—and some we have discussed already when we looked at the office of king—there is one message that runs like a water mark through motherhood such that it is manifestly part of all three: natural, supernatural, and transcendental. This is the message of extravagant love.

To understand this better, let us turn to Mary of Bethany as she anoints the feet of Christ. In her action, set in relief by the disgruntled response of the male disciples, I cannot but help see a spark of the feminine genius. In a fourteenth century painting of the story, by Dirk Bouts, there is a Dominican friar pictured to one side, who stares in amazement at the scene unravelling before his eyes. It is as if he has seen into the very heart of the ecclesial mission.

The way that Mark reports this event indicates its importance. Jesus singles Mary out for praise: “she has done a beautiful thing” (Mark 14:6). Only two people in the whole of Mark’s Gospel are directly singled out for praise: Mary, and two chapters earlier, another woman. Another woman who gives everything, even if this time all she gives are a few small pennies (Mark 12:41-44). Moreover, by merely mentioning this story at all, I am fulfilling a prophecy because Jesus says: “wherever the gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her” (Mark 14:9). Christ demands that this prophetic action be recorded and remembered in perpetuity.

Interestingly, Mark does not give a name to the woman (we learn that it is Mary of Bethany from John 12:3). This is, perhaps, to indicate that this act of extravagant love is an exemplar. Each and every believer is called to recognize what this genius recognized: Christ, like the alabaster jar, has allowed His body to be shattered for us so that the His Spirit might be poured out into our lives. The only possible response to this is an equally extravagant love on our side.

This wasting of oneself on the Lord seems to be the very essence of consecrated virginity. How often have we heard someone say about a bright, pretty, fun-loving, young woman who hears the call: “what a waste!” It is a wasted life, since it is a life wasted on the Lord: and, in this, it is a challenge to us all. And how often have we heard the same derision and accusation of waste turned against natural motherhood: “I am not going to stay at home looking after a bunch of snotty-nosed kids. changing diapers all day. I am going to make something of myself!”

The One Thing Necessary: Holiness

Let us finish with this last lesson of the feminine genius ringing in our ears; and the picture of a mother filling our vision.

Countless times, a new mother has been caught with a sleeping baby in her arms, and felt the pressure of all the chores piling up around her? And yet, she does not dare to put the child down in case he might awake. Then, her feminine genius comes to the rescue. She sees that it is much more important that she simply sit and commune with the child than that she has a clean house, manicured nails, or dinner ready for her husband on his return. She comes to the understanding of the very heart of her mission—love!

So what’s the point?

It is this: if a woman is seeking God with all her strength, if she is striving for communion with Him, then she is exercising, right here and right now, the highest and most important of ecclesial missions. The entire ministerial priesthood, the whole hierarchy of the Church, every article of Canon Law, is ordered toward this as an end—to support her as she strives for communion with God, and for holiness. What this world lacks, above all, are those who will waste themselves on the Lord. So, let us say, as St. Augustine said: “love and do what you will:” but for the future of society, and for the good of the Church, may it be done in a feminine way.

- John L. Allen, “Pope wants ‘capillary and incisive’ role for women in church” in National Catholic Reporter 25 Jan 2014 (http://ncronline.org/blogs/francis-chronicles/pope-wants-capillary-and-incisive-role-women-church, accessed 28 April 2016). ↩

- Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, §103. ↩

- John Paul II, Christifidelis Laici, §51. ↩

- John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem, §30. ↩

- John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem, §30. ↩

- John Paul II, Evangelium Vitae, §99.2. ↩

- Congregation for Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), Letter to Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Collaboration of Men and Women in the Church and in the World, §14. ↩

- Paul VI, Evangelii Nunciandi, §70. ↩

- CDF, Collaboration of Men and Women, §13. ↩

- John Paul II, Christifidelis Laici, §2. ↩

- John Paul II, Letter to Women, §2. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar “Women Priests?” Communio 22 (Spring 1995): 164-170. ↩

- Deborah Savage, “The Genius of Man” in Promise and Challenge, edited Mary Hasson (Huntington: OSV, 2015), 129-153. ↩

- CDF, Collaboration of Men and Women, §13. ↩

- Mary Eberstadt, “Offence, Defence, and Catholic Woman Thing” in Promise and Challenge, 243-354. ↩

- Pius XI, Casti Connubii, §27. ↩

- Cf. Mary Healy, “The Marian Style: The Feminine Genius in Evangelization,” Congress of Ecclesial Movements and New Communities, Rome, November 20-22, 2014. ↩

- Cf. Benedict Ashley, Justice in the Church: Gender and Participation (Washington D.C.: CUA Press, 1996). ↩

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, III q.54 a.4. ↩

- John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem, §21. ↩

Recent Comments