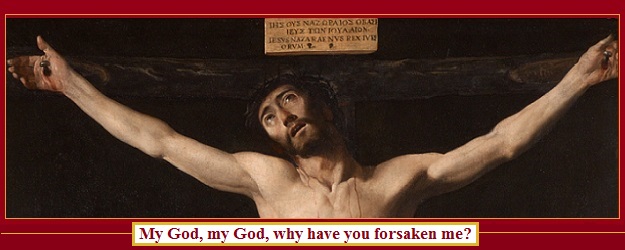

Jesus Crucificado Expirante by Francisco de Zurbaren, 1630-1640

“The New Testament is concealed in the Old, the Old Testament is revealed in the New.” These words of St. Augustine of Hippo have become axiomatic for Christian Scripture scholars. In particular, when a passage from the Old Testament is directly quoted or paralleled in the New Testament, the connection is not taken as coincidental. Rather, the Old Testament passage is viewed through the lens of the New Testament and vice versa. The Gospel of Matthew may be the New Testament text with the greatest explicit focus on this. Of the numerous Old Testament passages that are paralleled or directly quoted in the Gospel of Matthew, perhaps none is more well-known than Christ’s cry from the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” quoting Psalm 22. Several questions inevitably arise from this pericope, such as whether Christ was intentionally quoting the Psalm, and if so, what are the allusions and connections the hearer is meant to draw based on the Psalm’s original context; whether the Psalm was meant by the writer as a prophecy of a suffering Messiah, and if so what import the fulfillment of that prophecy in Christ has for Jews and Christians, both then and today; and how these passages—both individually and in tandem—can be a resource for Christian theology today, particularly in exploring the question of suffering and seeming abandonment by God. A detailed exploration of the cultural, literary, and theological contexts of both passages will illuminate the answers to these questions.

“Psalm 22 is the principal Old Testament resource employed by the evangelists to portray, and so interpret, the climax of Jesus’ career.”1 Matthew is no exception to this. The manner in which the events of the “climax of Jesus’ career”—that is, his Passion and death on the cross—are presented making it clear that Matthew is intending to demonstrate a direct link with Psalm 22, and bring that Psalm to the forefront of his hearers’ minds. The Psalm becomes an interpretive lens through which the Paschal Mystery of Christ’s suffering and death is to be understood. Matthew emphasizes every single similarity to the scene depicted in the Psalm, every single fulfillment of the Psalm, and every single fulfillment of Jesus’ prophecies.

Psalm 22 pervades the whole Passion story and points beyond it. … [T]he whole Passion is, as it were, anticipated in the psalm. Yet when Jesus utters the opening words of the psalm, the whole of this great prayer is essentially already present—including the certainty of an answer to prayer, to be revealed in the Resurrection, in the gathering of the great assembly, and in the poor having their fill (cf. vv.24-26). The cry of extreme anguish is at the same time the certainty of an answer from God, the certainty of salvation—not only for Jesus himself, but for “many.”2

Context for Psalm 22

An initial examination of the context—cultural, literary, and theological—of each passage will yield a more fruitful synthesis and analysis of the passages together.

The date and authorship of the Psalms are sources of great debate among Scripture scholars, as there are no clear, unequivocal indications in the text, and no outside sources to corroborate the possible textual clues. However, the information that the Psalms can provide regarding the cultural context in which they were composed can be invaluable, particularly in an exercise such as this, in trying to analyze how a Psalm relates to another part of Scripture. “Many psalms cannot be dated even approximately, but all we can glean about their background has real value.”3 Furthermore, in most cases “it is impossible to establish a relation to history.”4 As one scholar has aptly and succinctly described the situation, “we can here only make an attempt to shed light on occurrences lying in the darkness of the distant past.”5

While it may be impossible to date each Psalm precisely, we can make an educated guess at a general period during which the Psalms would have been composed. If we look at the development of Israelite religion developing from an outlook of many gods to the monotheistic religion it would become, “some scholars have dated the Psalms very late in Old Testament history. They have explained the presence of obviously ancient passages as due to the method of the late authors who, supposedly, drew on pieces of old psalms and built them into their new compositions.”6 This theory would have significant ramifications regarding authorship and historical context, if it were true. However, this hypothesis is not universally accepted, in large part because it cannot be demonstrated purely from the text. As a result, scholars tend to view the primary period in which the Psalms were composed as “lying between 1000 and 400 BCE, with the early part of this period as having been especially fruitful.”7

One particular ramification that flows immediately from this understanding of an extended period of composition is that the Psalms were certainly not all the work of a single author. While many of the Psalms are attributed to David, and it is accepted that David was a composer and singer of Psalms, current scholarship does not recognize the possibility of David as the composer of every Psalm contained in Scripture. “Without doubt the report that David wrote psalms, and sang them, goes back to historical fact. But the transmitters and collectors have obviously made rather liberal use of the notice “A Psalm of David.” They evidently found that the historical fact of David’s having written psalms was not adequately brought to light and, therefore, provided mostly the historically imprecise prayer songs of an individual.”8 This is not to say that the Psalms attributed to David were not in fact composed by him – but “we cannot determine authentic naming of poets in the Psalter. This fact raises for psalm research the question whom we should take to be the poets of the Psalms.”9 The Psalms, being primarily liturgical in nature, may well have been largely “the work of the priests and temple singers, who drew up the liturgies and formularies.”10

Now that we have examined the Psalms as a genre, it would behoove us to explore Psalm 22 in particular.

Psalm 22 is identified as a Psalm of lament by many scholars. Like other Psalms of lament, “Psalm 22 was composed for liturgical use. What one hears through it is not the voice of a particular historical person at a certain time, but one individual case of the typical. Its language was designed to give individuals a poetic and liturgical location, to provide a prayer that is paradigmatic for particular suffering and needs. To use it was to set oneself in its paradigm.”11 While it is tempting to try to identify the particular composer of this Psalm, and attempt to set him in a particular historical context to which the Psalm may refer, most scholars believe that the Psalm refers not to events in an individual’s life, but rather is a corporate prayer, perhaps meant to be relatable to any person. “Although many psalms are expressed as passionate statements of an individual, it is striking that there is scarcely anything that would identify any particular person.”12 This is abnormal for the ancient Near East, as archaeological discoveries have uncovered examples of similar literary genres, with specific circumstances and names detailed. And yet, it remains the case that Psalm 22 appears not to be linked with an individual in the centuries before Christ, but, as with other “individual lament psalms,” “there are absolutely no cases of unmitigated isolation present in these songs, but that the one who prays, participates in the prayer language of the community.”13

The liturgical, corporate character of the Psalms is important to emphasize here. Psalm 22 is not simply a historical record of an individual’s lament after a particularly trying experience in which he felt abandoned by God; it is meant to be relatable to all its hearers—the subject of the Psalm speaks along with all those who suffer and feel that abandonment.

Even in the days of the Old Covenant, those who prayed the Psalms were not just individual subjects, closed in on themselves. To be sure, the Psalms are deeply personal prayers, formed while wrestling with God, yet at the same time, they are uttered in union with all who suffer unjustly, with the whole of Israel, indeed with the whole of struggling humanity, and so these Psalms always span past, present, and future. They are prayed in the presence of suffering, and yet, they already contain within themselves the gift of an answer to prayer, the gift of transformation.”14

The Psalms are a theologically rich collection of hymns, and Psalm 22 is no exception. The declaration that God has abandoned one, and the pleading questioning of why, causes one to ask several questions. Does God abandon us? Has God shown fidelity in the past? Can we expect that God will still save us from this harm and suffering?

The Psalm opens with the repeated cry of “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps 22:1). The sense of anguish and despair communicated by this plaintive cry is increased by the repetition. “The repetition of the address is a sign of the depth of the affliction from which the petitioner issues his cry to God.”15 For one in the throes of affliction, whose enemies surround him, abandonment by God would be seen as the height of despair. In Jewish thought, God prevailed as the safeguard, the protector, the One whose might laid waste enemy armies, and opened the Red Sea to allow the Jews to cross. For such an ally to be nowhere to be found in time of greatest distress—even death—would have been the greatest fear. “The essence of all that is frightening is to be forsaken by God, and that is what is being suffered in this sphere of death (Ps. 22:1).”16 For the subject of the Psalm, the real pain comes not in God’s seeming abandonment, but in God’s silence following his cry. “Yahweh does not answer. This is where the real bitterness of forsakenness lies.”17

The heart of this passage can be seen in the verses that follow, in which the subject of the Psalm reflects on the fidelity God showed to His people in the past. In this, a profound sense of hope and trust is expressed.

While on the surface, the Psalm sounds like simply a cry of abandonment and disillusionment, at its heart, it remains a hymn of trust in the Lord—who permits evil and suffering, but remains steadfast. He turns from his sufferings to think about God [in verses 3-5]. He is the holy ruler of all, worshiped by Israel, so that the apologetic problem of a holy and all-powerful God’s permission of evil, although not made explicit, may be in his mind. 18

This is why the subject cries out in his torment: not only does he feel abandoned by God in that moment, and he laments his predicament, but he knows that God will hear him, and trusts that he will be answered in God’s mercy. “The conviction of being heard, the very heart of songs of lament and petition, lives on the unshakable reality that the God of Israel showed grace to the fathers who turned to him, and he helped them (Ps. 22:4f.).”19 This constancy of Yahweh is what gives the speaker confidence and trust. There is a thread running throughout the Psalm that God will not abandon one forever, even if he seems to have forsaken one in a given moment. Again, this all comes down to God’s history of support of Israel. “The support for the trust expressed in the cry is Yahweh’s constant display of power and blessing in Israel (vv. 3-5).”20 The sufferer clings to his God, lamenting what he feels as abandonment, but never relenting in his faith.

The speaker’s sense of God’s constancy is not present only in verses 3-5. This is a theme running throughout the Psalm, which colors and informs our understanding of the way in which the subject handles his time of distress, and what the reader or hearer should learn from this—namely, that God is steadfast in fidelity to his people. In verses 9-11, “…he emphasizes that the one he addresses had always been his God, and he had always trusted him.”21 Ultimately, this is where the subject’s consolation lies: the fact that God has helped those who trusted in him, and “Yahweh’s power has proved itself among the fathers.”22 It is a precedent in which the lamenting petitioner, and all those who suffer yet trust in God, can find consolation.

Context for Matthew 27:27-46

We follow our examination of the context surrounding Psalm 22 with an examination of the context and background of the Gospel of Matthew, and in particular the 27th chapter. First, the matter of authorship and date of composition of the gospel.

As early as the beginning of the second century AD, we have record of Papias attributing this gospel to the apostle Matthew. This is significant given the immediate historical proximity of Papias to the writing of the gospel. Furthermore, “there is not a hint that anyone claimed someone else as the author of Matthew.”23 The authorship of this gospel was not debated in the years, and indeed centuries, immediately following its composition. “Attribution of this gospel to Matthew the apostle goes back to our earliest surviving patristic testimonies, and there is no evidence that any other author was ever proposed.”24

The date of authorship of the gospel is a matter of heated debate. Many scholars feel that it must have been composed after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD. However, this is not a view universally accepted by scholars. While “[t]he principal argument for a post-70 [AD] date is the possible allusion to the burning of Jerusalem in the parable of the wedding banquet (Matt 22:1-14)”, “the detail of fiery destruction in Matthew’s parable may be nothing more than biblical language.”25 Furthermore, it is possible that the parable was “glossed to reflect the destruction of Jerusalem. Scribes did gloss over Scripture here and there, as the discovery of early New Testament manuscripts has shown.”26 It is also possible that the seeming allusion to the burning of Jerusalem is coincidental, or even prophetic. However, “recent major commentaries on Matthew have reached” the conclusion that there are “reasonable arguments for the writing and circulation of all three Synoptic Gospels sometime prior to the war of 66-70 AD.”27

Examining Psalm 22, and familiarizing ourselves with the text and context prior to exploring the Gospel of Matthew, is fitting, as Matthew’s audience would have been particularly familiar with the Psalms, and other sacred writings of the Jews. This is the trend throughout the entirety of Matthew’s gospel, which has led scholars to posit that Matthew was writing for a primarily Jewish audience. “Most scholars would now agree that the gospel derives from a largely Jewish-Christian community”.28 If we have established that Matthew is writing for a Jewish audience, the question remains: why? Why focus his efforts on that particular group? “[A] number of scholars have reached the … conclusion … that Matthew is still in the Jewish community, struggling to convince a skeptical synagogue that Jesus really is Israel’s Messiah, that his teaching really does measure up to the righteous requirements of the Law of Moses, and that his death and resurrection really have fulfilled prophecy.”29 This fact is critical to understanding Matthew’s account of Jesus’ crucifixion. As he was trying to convince Jews that Jesus was Israel’s Messiah, fulfilling the prophecies, Matthew continually emphasizes (both explicitly and implicitly) the ways in which the events of Jesus’ life demonstrate this.

Matthew’s account of this climax of Jesus’ public ministry is “uncharacteristically full of vivid details.”30 Why would Matthew include such vivid detail here, when he did not customarily do so elsewhere in his gospel? It seems that this was done in order to more clearly outline the parallels between this scene and the Old Testament accounts that are reflected in it. Unlike in many other places in his gospel, Matthew does not draw attention to the parallels by stating something was done in order that a prophecy might be fulfilled—he trusted his readership to be fully aware of the parallels, and to draw their own conclusions. What is Matthew trying to accomplish on a theological level in drawing such clear connections between the scene of Jesus’ crucifixion and Psalm 22?

In verse 46, Jesus utters the cry of the beginning of Psalm 22: “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” This cry would not have simply been viewed as a cry of despair by Matthew’s audience. Many scholars suppose that “our evangelist and his first readers would have understood the quotation of Ps 22.2 to be like a Jewish midrash, in which the first part of a verse is quoted and the rest assumed; and as Psalm 22 moves on from complaint to faith and praise, so should Jesus’ words imply the same.”31 The entirety of the Psalm would have been brought to the forefront in the minds of the audience, and they would have understood Jesus’ cry as fundamentally a recognition of his trust in God, in spite of his forsakenness at that moment.

It is certainly true that Jesus did feel this forsakenness. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus’ despair over what he knew was about to befall him was real, yet he accepted the cup that was before him. This scene of the crucifixion follows “after Gethsemane where Jesus has accepted that he must drink the cup to the full: he did not expect to be rescued. The words Jesus chose to utter are those of unqualified desolation, and Matthew and Mark (who alone record this utterance) give no hint that he did not mean exactly what he said.”32 However, by his constant allusions to Psalm 22, Matthew intends to bring the entirety of the Psalm, including the subject’s trust in God, and ultimate praise for the work God has done, to a place of prominence.

The way that Jesus addresses God in this scene is significant. For the first and only time, Jesus addresses God as “God,” rather than “father.” “Everything happens as if, in this last hour, the experience of sonship has given way to that of creature-hood. Jesus cries forth his anguish, but in the form of a dialogue: he still proclaims his trust (“my God”), his certainty that God is still with him despite all appearances to the contrary.”33 This is a profound statement of despair, abandonment, and separation from his father. More than this, he is identifying himself with all of Israel, and all who feel abandoned by God at some time or other. “It is no ordinary cry of abandonment. Jesus is praying the great psalm of suffering Israel, and so he is taking upon himself all the tribulation, not just of Israel, but of all those in this world who suffer from God’s concealment. He brings the world’s anguished cry at God’s absence before the heart of God himself. He identifies himself with suffering Israel, with all who suffer under “God’s darkness”; he takes their cry, their anguish, all their helplessness upon himself—and in so doing he transforms it.”34

Jesus transforms the anguish and helplessness by the vindication that is to come. As addressed above in our discussion of Psalm 22, Jesus’ cry elicits hope—hope and trust that God will save him in the end. After expressing “the depths of his unimaginable pain at being abandoned by his Father,” and the “unfathomable agony” of that abandonment, it becomes clear that “his abandonment is only temporary, and his vindication will come soon.”35

Each of these passages is profound and meaningful in its own right, in its own context. However, returning to our axiom from St. Augustine, “The New Testament is concealed in the Old, the Old Testament revealed in the New.” We will now explore how these passages relate to one another in greater depth, and how, working in tandem, they can inform theological and pastoral discussions today.

Synthesis and Analysis

It is nearly impossible to examine the texts of Psalm 22:1-18 and Matthew 27:27-46 without exploring the other, so intrinsically are these passages connected. When explored in greater depth, this connection yields profound insights for theology and ministry.

How are these passages connected? As explored briefly above, the language of the Psalm, “arising initially out of the psalmist’s experience,” uses “language peculiarly appropriate to Christ’s sufferings and vindication.”36 As a result of this peculiar and inescapable correlation, scholars have taken to dealing with these passages as a virtually inseparable pair. The Psalm becomes a hermeneutical lens through which to read and understand the Passion of Christ, and the Passion becomes a light that cuts through the fog surrounding the meaning of the Psalm. “The experiences of the one who prays in the psalm become part of the scenario of the passion. So, the Gospels draw a connection not only between the prayers of Jesus and the psalm, but as well between the person of Jesus, and the person portrayed in the self-description of the psalm.”37 To be clear, this is not a method foreign to Judaism that modern scholarship is placing upon the passages by a sort of academic fiat. This is an established tradition: “In the intellectual world of Judaism, one of the most important ways of understanding the meaning of present experience was to make sense of the contemporary by perceiving and describing it in terms of an established tradition. That seems to be happening in the connection between psalm and passion story.”38

It is significant to note that Matthew’s presentation of the events of the crucifixion, while explicitly reflecting Psalm 22, are not presented in the common “prophecy fulfillment” formula so often utilized by Matthew. There is no clarifying statement of “This was done to fulfill” or “This was as had been written.” Matthew seems to feel that his audience will be so familiar with the Psalm and other writings referenced that they will not need this reminder—and perhaps, he also does not wish to distract from the events at hand. “This haunting scene depicts Jesus as the suffering, righteous one, akin to the figures in Psalm 22, Isaiah 53, and Wisdom 2; and perhaps its outstanding feature is its scriptural language. Although the OT is not formally introduced, its presence is recurrent.”39

What in particular do these passages together have to say to the hearer? How does Matthew’s emphasis of the parallels with Psalm 22 affect how his narrative is interpreted? Fundamentally, these two passages show us that when we suffer, when we feel abandoned by God, when we feel that all hope is lost, and we are utterly alone—we are not alone. Not only has Christ suffered the same abandonment, but he brought this sense of abandonment before the throne of God. The scene of Jesus’ crucifixion becomes in a sense a fleshed-out narrative of the scene depicted in Psalm 22. The universality and corporate character of Psalm 22, as discussed above, becomes concretized in the person of Jesus Christ, who, by virtue of his salvific work for all, helps to apply the Psalm concretely to all who have suffered, and are yet to suffer. He identifies himself with these sufferers and joins them. “That is, first of all, what Jesus does in his anguished cry to God when he begins to recite the psalm. He joins the multitudinous company of the afflicted, and becomes one with them in their suffering. In praying as they do, he expounds his total identification with them. He gives all his followers who are afflicted permission and encouragement to pray for help. He shows that faith includes holding the worst of life up to God.”40

The fact that Jesus concretizes the experience of the petitioner in the Psalm “does something to suffering that changes its face for those who believe in him. Suffering becomes something he has been through at its typical worst. The change is not something empirical, but experiential. We can grasp the dimensions of the change if we could imagine ourselves thinking of suffering only as something from which God is absent, or which God inflicts on people.”41 This change is effected by Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, and the abandonment and forsakenness he feels. In essence, it is because Jesus knows what it’s like. “Knowing ‘he has been through it’ does not give us a final explanation or metaphysic. It does give us a new perspective, experience, and stance.”42

It is not to be believed that Jesus, being the Son of God, did not truly suffer, and only took on the appearance of suffering for the sake of later generations being able to relate to him. “The Gospel accounts make it very clear that he suffered and died as one of the ‘lowly.’ In the psalm, it is the dying of one who trusts in the Lord that raises the question about God, and it is his salvation that leads to the knowledge that God ‘has not despised or abhorred the affliction of the afflicted’ (a very real possibility to Old Testament people and to moderns).”43 Furthermore, because of what happens following Jesus’ death—which is relatable to the closing of the Psalm—the hearer is shown that “whatever the anguish caused by the conflict of faith and experience may mean, it does not mean that God has failed those who cry to him. For the lowly, the passion and resurrection of Jesus is a justification of God in whom they trust, and a vindication of their trust.”44

Finally, it should be understood and recognized that the relatability of this passage does not apply merely to those in Judeo-Christian religions, but to all men universally. Suffering and death are universal, not to be escaped by any man. As a result, all men can relate to Christ in his plaintive cry from the cross—and thus, all men can share the hope of Christ that is communicated in his own steadfast trust in God.

[H]is resurrection is the signal to all who dread and undergo the threefold loss that death itself has been brought within the rule of the God of Jesus Messiah. It is the news that is of ultimate concern for all humanity.45

Whatever our situation in life, our cultural setting, our vocation, the blessings we enjoy, or the crosses we bear, the hope-in-suffering-and-abandonment of Christ speaks profoundly to us, and Christ urges us to share in that hope. Christ’s cry of abandonment “does not express a loss of faith—certainly the soldiers who soon confess Jesus Son of God have seen no such loss—but is instead a cry of pain in a circumstance (unparalleled elsewhere in the narrative) in which God has not shown himself to be God. And yet the truth, apparent from what follows, is that God has not forsaken Jesus. The abandonment, although real, is not the final fact. God does finally vindicate his Son.”46. This is the crux of the matter. In a pastoral setting in particular, this is where the “rubber meets the road”: Jesus Christ, the Second Person of the Trinity, become incarnate, felt the abandonment of God, felt the distress we all feel at times, in his hour of greatest need. And yet, God remained steadfast, and he was vindicated in the end. Perhaps the most trying question to be asked as a pastor or minister is, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” or “Where was God when this happened?” The answer lies in the words of Christ from the cross, and the entirety of the Psalm that those words bring with them. As demonstrated in the Psalm and the correlative gospel narrative, God will never abandon his people, those who trust in him.

- James Luther Mays. “Prayer and christology : Psalm 22 as perspective on the passion.” Theology Today 42, no. 3 (October 1, 1985): 322. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials, EBSCOhost (accessed October 21, 2013). ↩

- Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth – Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011), 214. ↩

- Geoffrey Grogan, Psalms (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2008), 7. ↩

- Hans-Joachim Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 63. ↩

- Ibid. 68 ↩

- J.H. Eaton, The Psalms: a historical and spiritual commentary with an introduction and new translation (London: T&T Clark International, 2003), 4. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 64. ↩

- Ibid., 65 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mays, “Prayer and christology : Psalm 22 as perspective on the passion,” 323. ↩

- Eaton, The Psalms: a historical and spiritual commentary with an introduction and new translation, 5. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 40. ↩

- Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth – Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, 215. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 294. ↩

- Ibid., 78 ↩

- Ibid., 295 ↩

- Grogan, Psalms, 72. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 77. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 295. ↩

- Grogan, Psalms, 73. ↩

- Kraus, Psalms 1-59: a continental commentary, 295. ↩

- Craig A. Evans, Matthew (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 3. ↩

- R.T. France, The Gospel of Matthew (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2007), 15. ↩

- Evans, Matthew, 4. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 5. ↩

- France, The Gospel of Matthew, 15. ↩

- Evans, Matthew, 6. ↩

- W.D. Davies, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998), 598. ↩

- Davies, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, 625. ↩

- France, The Gospel of Matthew, 1076. ↩

- Xavier Léon-Dufour, Life and Death in the New Testament: The Teaching of Jesus and Paul (San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1986), 127. ↩

- Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth – Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, 214. ↩

- David L. Turner, Matthew (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 669. ↩

- Grogan, Psalms, 72. ↩

- Mays, “Prayer and christology : Psalm 22 as perspective on the passion,” 322-323. ↩

- Ibid., 323 ↩

- Davies, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, 608. ↩

- Mays, “Prayer and christology : Psalm 22 as perspective on the passion,” 323. ↩

- Ibid. 330 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 331 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Davies, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, 625. ↩

Recent Comments