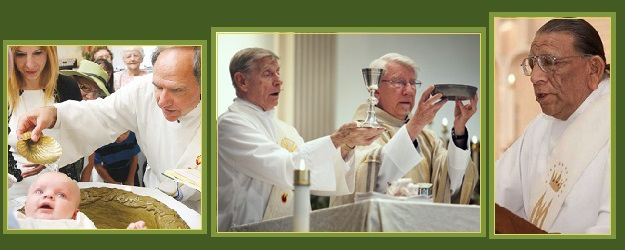

Permanent deacons baptizing, assisting the priest during Mass, and reading the Gospel.

Robert Cardinal Sarah, the Prefect for the Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, delivered a riveting, yet controversial, address to the attendees of Sacra Liturgia Conference in Rome in July 2016. The Prefect admitted in his reflections that much work is still needed to actualize the vision of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council, but the singular issue of ad Orientem worship in the Roman Liturgy unfortunately overshadowed his talk.1 The call, however, for the continued renewal of Sacrosanctum Concilium is a legitimate work of the post-Conciliar Church.

In the meantime, Pope Francis met with a group of Catholic women, in May 2016, for the triennial meeting of the International Union of Superiors General (UISG). Some religious prodded the assembly to discuss the issue of the legitimacy of “deaconesses” in the Church, with the hopes that the Pope would officially explore the question, and its relevance for the Church today. Pope Francis delivered on his promise with the establishment of a special commission in August 2015, and the question is still being explored.2

It seems no accident that these events coincided with the upcoming 50th Anniversary of Pope Paul VI’s Apostolic Letter, Sacrum Diaconatus Ordinem, on the restoration of the permanent diaconate. It seems advantageous to consider the liturgical potential of the permanent diaconate in the continued renewal of the Church’s liturgy. This article will argue through the perspective of current legislation and theology that the permanent diaconate has the potential to contribute to the ongoing renewal of the Church’s liturgy, while also being transparent about real issues and challenges.

The Second Vatican Council and Subsequent Legislation

The Second Vatican Council acknowledged the three-fold hierarchy of the Church’s ordained ministry. In treating the diaconate, the Council Father’s reminds the Church (emphasis mine):

At a lower level of the hierarchy are deacons, upon whom hands are imposed “not unto the priesthood, but unto a ministry of service.” For strengthened by sacramental grace, in communion with the bishop and his group of priests, they serve in the diaconate of the liturgy, of the word, and of charity to the people of God. It is the duty of the deacon, according as it shall have been assigned to him by competent authority, to administer baptism solemnly, to be custodian and dispenser of the Eucharist, to assist at and bless marriages in the name of the Church, to bring Viaticum to the dying, to read the Sacred Scripture to the faithful, to instruct and exhort the people, to preside over the worship and prayer of the faithful, to administer sacramentals, to officiate at funeral and burial services. Dedicated to duties of charity and of administration, let deacons be mindful of the admonition of Blessed Polycarp: “Be merciful, diligent, walking according to the truth of the Lord, who became the servant of all.3

The Council Fathers are very clear that the diaconate is linked to the Church’s sacramental life. The “diaconate of the liturgy” is listed first amongst the duties of the deacon for the good of the Church. The paragraph mentioned specific duties of the diaconate, most of which are related to the dispensation of the Church’s liturgical wealth. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that Pope Paul VI assumes the deacon’s liturgical dimension when exhorting, in his Apostolic Letter, Sacrum Diaconatus Ordinem, that they should “assist the bishop and priest during liturgical actions in all things which the rituals of the different orders assign to him.”4 The Congregation for Clergy affirmed, in its 1998 declaration entitled Directory for the Ministry and Life of Permanent Deacons, the Second Vatican Council’s deliberate relation of the diaconate with the Church’s liturgy: “Deacons receive the Sacrament of Orders, so as to serve as a vested minister in the sanctification of the Christian community, in hierarchical communion with the bishop and priests.”5 The declaration continues that the diaconate, while not celebrating the Mass, orients and directs the active participation of the assembled community. It is evident, therefore, that the diaconate serves as a sign in communicating the depth of the Church’s liturgy.

The liturgical dimension of the diaconate is not at the expense of its other functions, namely: the ministry of the word, and the ministry of charity. It is in the Church’s liturgy that the three are “concentrated and integrated.”6 Official legislation runs, therefore, contrary to anyone who would deny the significance of the diaconate in the Church’s liturgy. The permanent diaconate, moreover, assures the presence of this important minister in the ordinary experience of parishes. How does the diaconate communicate on a theological level the depth of the Church’s liturgy? This question is intimately related to three qualities currently being reclaimed and appropriated in sacramental circles: the sacred, signs, and solemnity.

Signs and the Communication of the Sacred

Uwe Michael Lang offers, in his just released work, Signs of the Holy One, poignant and relevant meditations on the reality of the sacred. Lang, taking his cue from prominent theologians and sociologists, beautifully relates the Church’s liturgy as flowing and participating in the divine Godhead, the source of all Sacredness. The Church’s liturgy is only sacred in that it is a participation in the priestly work of Jesus Christ who, in his mystical body, is offered to, and returned from, the Father. Lang affirms Sacrosanctum Concilium’s understanding that the reality of the Church’s liturgy is communicated through signs and symbols perceptible to the senses.7 The Church, in her wisdom and reflection, acknowledges the anthropological foundation of symbolic mediation in our everyday experience, and she uses this to her advantage in communicating the sacredness of God. Lang’s insights reflect the Catechism’s reminder that any sacramental celebration is “woven of signs and symbols.”8 Not all signs, however, are created equal. The Catechism supplies a four-fold criterion for evaluating the legitimacy of different signs, namely: creation, human culture, the Old Covenant (Testament), and Christ.9 Genuine signs are rooted in these four dimensions of meaning that communicate the depths of the Paschal Mystery. How does the diaconate—or the function of the diaconate—measure against these criteria? It is now advantageous to look at these individually.

Creation

There were certainly no deacons at the dawn of creation. Does there exist, however, a created order that embodies the diaconate’s three-fold ministry of word, charity, and altar? We read in the Book of Revelation that angelic hosts minister at the altar of God (Revelation 8:3). Christians, and non-Christians, affirm their bearing God’s word, and we can also be certain that the angelic hosts exercise charity in their ministry to the human race.

The deacons, in turn, were associated throughout the Tradition with the angelic hosts. St. Ignatius of Antioch, in his Epistle to the Trallians, reminds the Church, “…and what are the deacons but imitators of the angelic powers, fulfilling a pure and blameless ministry unto him, as the holy Stephen did to the blessed James, Timothy, and Linus, to Paul, Anencletus and Clement to Peter?”10 St. Clement of Alexandria, in his Stromata, says that all three ministries—bishop, priest, and deacon—are “imitators of the angelic glory of the heavenly economy.”11 Narsal, a Father of the Nestorian Church, is consistent with this theme: “He (St. Stephen) was made a deacon of the dread divine mysteries; and in his ministry, he depicted a type of the angels. This type, the deacons, bear in Holy Church, imitating in their ministry the hosts of the height.”12

The Order of the Diaconate, and the Angelic hosts, are almost synonymous in the Christian East. The Iconostasis, a large screen that separates the nave from the sanctuary, is typically adorned with various icons. The placement of the icons is not a random process, but the icon’s position on the Iconostasis is fixed, and reveals a purpose. Side doors, often times used by the deacons during different parts of the liturgy, are traditionally adorned with either angels or saintly deacons.13 Angels in traditional iconography are vested in the vestments of the deacon, and statuary, in some older Catholic Churches, follow suit in angels vested in dalmatics.

Is this, however, just pious association? Do the deacons stand as a true icon of the angelic realities? Cardinal Ratzinger, in his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy, recognized three spheres in the history of salvation: shadow, image, and reality.14 Shadow, of course, represents the Old Covenant, and the story of our ancestors in the Faith. The image—representative of our present age—is the kingdom initiated by Christ’s resurrection on earth. Ratzinger bemoaned the temptation to think this age is the end-all-be-all of salvation history. The Church must remember that the present, earthly liturgy, while mindful of the shadow and the image, is also cognizant of its eschatological fulfillment. The reality is the time when we will no longer need signs and symbols in communicating the mysteries of our Faith. This is the telos of Christianity, but our present age is not the actualization of this hope. Our liturgy is eschatological in its acknowledgement that our earthly liturgy is but a participation in the heavenly liturgy. With this in mind, it would seem that a vested deacon ministering at the altar is a powerful symbol of the angelic hosts ministering at the altar of heaven. This is more than a pious association, but it has the potential to be both a spiritual and mystogogical opportunity.

Human Culture

A servant in our everyday human experience is one who performs duties for others. The word “servant” is used over 800 times in the Bible, and the majority of these instances are related usually to slavery. The chief characteristic of slavery, in the ancient and contemporary world, is that a servant has no legal rights, but the biblical definition also had this element of humble self-designation.15 It should be no surprise, therefore, that the literal meaning of the word deacon is “servant.” The servile, however, touches even on the very word, “liturgy.” The word λειτουργία comes from the two Greek words: Laos, the “people,” and ergon, meaning “work.” In the ancient world, someone who did liturgy was a public servant, much like our modern day sanitation engineer.16 The priest in a Christian Liturgy certainly offers a public service by offering the sacrifice of Christ, but the Deacons also minister on behalf of the faithful gathered, most especially in facilitating active participation.

Old Covenant

There is a sense in the Church’s liturgical tradition that the hierarchy of the New Covenant is somehow related to the ministers in the Old Testament. The singing of the Easter Proclamation at the Easter Vigil, while traditionally sung by a deacon, names him as one “among the Levites.”17 The prayer of consecration at the ordination of a deacon echoes this sentiment: “As ministers of your tabernacle, you chose the sons of Levi and gave your blessing as their everlasting inheritance.”18 St. Ambrose, in his De Sacramentis, writes in his baptismal catechesis: “You saw the Levite, you saw the priest, you saw there the chief priest. Consider not the bodily form, but the grace of the mysteries.”19

The role of the Levites in the Old Covenant is somewhat confused since the time when they were traditionally distinguished from the “descendants of Aaron.” These Aaronites, while technically sometimes regarded as subsets of the Levites, were distinct in their ministry from the priests. In the book of Numbers, we read that the Levites were called to minister to Aaron (Numbers 3:6; 18:2). They were certainly allowed to handle the furnishings for the meeting tent, but it was only the descendants of Aaron that were to offer sacrifice (Numbers 3:7-10).20 The priests of the New Covenant offer the Sacrifice of Christ, but the deacons assume the responsibilities of assisting these priests in their liturgical ministry. Recalling Ratzinger’s distinctions of salvation history, the shadow of the ancient order is revealed in the ministrations of the New Covenant.

Christ

The ministry of the diaconate is associated with the men in Acts 6. Their relationship to the modern-day diaconate is dubious, in some circles, but the association obviously came through the common call of charity (Acts 6:2). The hard dichotomy between charity, word, and altar is an illusion since Philip, one of the seven appointed, preaches the Gospel at different times through the Acts of the Apostles, most notably in his work with the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8: 26-40).

We understand that the cultural meaning of a servant is a reality that extends into our present age. Our Lord Jesus Christ, in his initiating a new age, reminds the faithful that anyone who wants to be first must “be a slave to all“ (Mark 10:44). He reminds his followers to not seek seats of honor, but to seek humility (Luke 14: 7-14), and he continued that “the first shall be last, and the last shall be first” (Mather 20:16). The Lord Jesus Christ, however, exercised his humility in the tangible move of the foot-washing scene in John’s gospel. Our Lord, providing an example, acknowledged his place as master and teacher while humbling himself to accomplish such a servile task. The deacon, moreover, attends to the needs of the priest in the Sacrifice of the Mass. He embodies, alongside the priest, the call of St. John the Baptist: “I must decrease, he must increase” (John 30:3).

The most profound humbling, however, is our Lord’s incarnation. St. Paul reminds us:

Have among yourselves the same attitude that is yours in Christ Jesus, who thought he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, death on a cross. Because of this, God greatly exalted him and bestowed upon him the name that is above every name, that at the name of Jesus ever knee should bend, of those in heaven and on the earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (Philippians 2: 5-11).

Our Lord Jesus humbled himself in becoming “sin, who did not know sin” (2 Corinthians 5: 21). In his assuming our human nature, our Lord Jesus Christ assumed the “form of a slave” wounded by sin.

Solemnity

The question of solemnity is a renewed inquiry pursued by many serious theologians and scholars.21 It must be admitted that solemnity was a more precise science with the pre-Conciliar liturgy. The absolute distinctions between “Low” and “High” Mass made questions of liturgical praxis moot. This peculiarity, however, led to the unfortunate proliferation of Low Masses in the Church’s Sunday experience. A congregation’s inability to master music certainly contributed to this state, but the absence of ministers—especially deacons—meant the near-impossibility of a Solemn High Mass. It would seem, therefore, that Latin Mass communities could be the most benefited by the permanent diaconate.

A different principle, however, guides solemnity in the post-conciliar Church: Progressive Solemnity. The standard makes its first appearance in Musicam Sacram with respects to the Divine Office,22 but the USCCB extends the principle to the sung parts of the Mass,23 and its extension into the ceremony of the Mass—while not explicit—is often times assumed. The presence of the deacons at the Eucharistic liturgy ups the solemnitas of a liturgical celebration, and their presence should not be seen as accidental, but vital to more solemn celebrations.

Contemporary Challenges

What is the possibility, therefore, of the permanent diaconate’s involvement in the Ordinary Form of the Mass? The deacon’s presence should be, first, assumed for solemn celebrations of the Mass. It is permissible for concelebrating priests to undertake the role and duties of the deacon, but an actual deacon—ordained and vested—serves as an icon to countless theological dimensions. Three deacons are assumed to be needed for a Stational Mass of the Diocesan Bishop, but how many times is this option not actualized?24 The permanent diaconate is intrinsic to more solemn celebrations of the Eucharist, and their presence is as essential to the rites as is music, incense, and other signs, and gestures. The deacon communicates—on a deeper level—something both mystogoical and eschatological.

There is, however, in many places a crisis in the diaconate, devoid of the above-mentioned theology. Pastors bemoan ill-prepared and unconfident deacons assisting at the altar. An office of the Church, itself modeled after the Angelic Hosts, is relegated to indifference, and the position of glorified altar servers—what a shame! What can be done liturgically to remedy this reality? How can our public prayer help to recapture the dignity due to the diaconate? The possibilities are many, but one can focus their efforts on three dimensions: vesture, Mass parts, and singing.

Vesture

The General Instruction of the Roman Missal reads:

The vestment proper to the Deacon is the dalmatic, worn over the alb and stole; however, the dalmatic may be omitted out of necessity or on account of a lesser degree of solemnity.25

The Church specifies five pieces of vesture that can be worn by the Deacon which include an alb, cincture, amice, stole, and dalmatic; but the General Instruction of the Roman Missal does imagine situations when one or the other might be omitted.26 The dalmatic, however, is the vestment of the Deacon. The Church allows for its omission, but can one admit that these exceptions have unfortunately become the norm? Pastors should be attentive in guaranteeing appropriate vesture for everyone participating in the liturgy, most especially the Deacon. It is conceivable, moreover, that the dalmatic could be worn daily.

Deacon Participation in the Mass

Too many deacons in the Latin Church are either convinced, or forced into, forgoing their roles. The Third Edition of the Roman Missal—itself an improvement on the previous editions—provides several instances of diaconal duties: the proclamation of the Gospel,27 the preparation of the gifts,28 the proclamations of the Universal Prayer,29 and the dismissal.30 Deacons should not, therefore, be satisfied with assuming the role of liturgical flowerpots. Their presence adds to the solemnity of the Mass, and speaks to the dignity/purpose of the diaconate.

Singing

There is a venerable tradition for chant and music in our liturgy. The Third Edition of the Roman Missal makes it possible to sing the entire Mass from beginning to end. Singing is a powerful sign that communicates something ordinary speech does not. While the deacon could conceivable sing all his dialogues, there is one instance when the Church’s liturgy calls for a deacon to most especially sing: the Exultet at the Easter Vigil.31 Many parishes opt to have a cantor/layman sing the text of the Exultet at Mass, but it is trimmed in this instance to exclude particular references to the deacon.

Conclusion

Many of the above reflections are only possible with the pastor’s discretion. It is important, therefore, that priests recognize and acknowledge the dignity of the diaconate. Irrational fear or hostility is unacceptable and nonsensical. With our combined efforts, we can effectively “restore all things in Christ” (Ephesians 1:10). The diaconate is certainly affirmed and assumed by the Church’s most contemporary legislation. The anniversary of Sacram Diaconatus Ordinem is a cause for rejoicing, but also an opportunity for continued reflection and purpose. On a theological level, the deacon serves as an icon for countless moral and theological dimensions in the sacred liturgy. Their presence serves as a window to encounter the sacred, and their role in both the Ordinary and Extraordinary Forms of the Mass—with respects to solemnity—is unparalleled. The Church must double-down its efforts to bring this venerable rank to full stature. This will only come about with quality catechesis and sound liturgical formation. With these things in mind, the men called to service in the 21st Century will certainly be in the venerable line of deacons who came before.

- Dan Hitchens, “Cardinal Sarah Asks Priests to Start Celebrating Mass Facing East This Advent,” Catholic Herald, July 5, 2016, accessed September 12, 2016, catholicherald.co.uk/news/2016/07/05/cardinal-sarah-asks-priests-to-start-celebrating-mass-facing-east-this-advent/. ↩

- Joshua J. McElwee, “Francis Institutes Commission to Study Female Deacons, Appointing Gender-balanced Membership,” National Catholic Reporter, August 2, 2016, accessed September 12, 2016, ncronline.org/news/vatican/francis-institutes-commission-study-female-deacons-appointing-gender-balanced. ↩

- Second Vatican Council, “Constitution on the Church,” in Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, ed. Austin Flannery (Northport, NY: Costello Publishing Company, 1996), #29. ↩

- Paul VI, “Moto Proprio Sacrum Diaconatus Ordinem (General Norms for Restoring the Permenant Diaconate in the Latin Church),” in Compendium of the Diaconate: A Resource for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of Permanent Deacons (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2005), #20.1. ↩

- Congregation for the Clergy, “Directory for the Ministry and Life of the Permenant Deacons” in Compendium of the Diaconate: A Resource for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of Permanent Deacons (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2005), #28. ↩

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “National Directory for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of the Permanent Deacons in the United States,” in Compendium of the Diaconate: A Resource for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of Permanent Deacons (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2005), #34. ↩

- Uwe Michael Lang, Signs of the Holy One: Liturgy, Ritual, and Expression of the Sacred (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2015), 126. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Libreria Editrice Vaticana-United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2000), par. 1145. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ignatius of Antioch, “The Epistle of Ignatius to the Trallians,” in The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 69. ↩

- Clement of Alexandria, “The Stromata, or Miscellanies,” in Fathers of the Second Century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria (Entire), ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, vol. 2, The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 505. ↩

- Narsai, “The Liturgical Homilies of Narsai” in Texts and Studies, ed. J. Armitage Robinson, Vol VIII (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1916), xxiv. ↩

- Edward Faulk, 101 Questions and Answers on Eastern Catholic Churches (New York: Paulist Press, 2007), 80. ↩

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 54. ↩

- Frank J. Matera, “Servant,” ed. Mark Allan Powell, The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 939. ↩

- F. L. Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 994. ↩

- The Easter Proclamation, in The Roman Missal, trans. The International Commission on English in the Liturgy, 3rd typical ed., sec. 88 (Washington D.C.: United States Catholic Conference of Bishops, 2011), 347. ↩

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, “The Roman Pontifical” (Vatican City, Vox Clara Committee, 2012), #235. ↩

- Ambrose of Milan, “On the Mysteries,” in St. Ambrose: Select Works and Letters, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. H. de Romestin, E. de Romestin, and H. T. F. Duckworth, vol. 10, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1896), 317. ↩

- Joshua R. Porter and Mark Allan Powell, “Levites,” ed. Mark Allan Powell, The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 556. ↩

- See Peter Kwasniewski, Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2014), 11-33. ↩

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, Instruction Musicam Sacram (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1967). ↩

- See United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship,” (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2007), 41. ↩

- Ceremonial of Bishops, trans. The International Commission on English in the Liturgy, (Collegeville MN, The Liturgical Press, 1989), #122. ↩

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2010), #338 ↩

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The General Instruction of the Roman Missal, # 336 ↩

- Ibid., # 171c ↩

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The General Instruction of the Roman Missal, # 178 ↩

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, The General Instruction of the Roman Missal, #171d ↩

- Ibid., # 185. ↩

- The Easter Proclamation, in The Roman Missal ↩

This is a splendid article that raises important questions, especially about solemnity, vestments, and singing. However, the Extraordinary Form also needs amendment to account for the document, lest the EF be stuck in the nineteen-sixties. As I recall, Sacrosanctum Concilium goes with both forms. There should be a change to allow a deacon to assist at a non-solemn sung Mass.

I am a deacon. I am a cleric. I understand my role in the Church–I am the sacramental sign of Christ the Servant. I am a witness to charity among the people of God. All deacons are clerics which is not “clericalism” Deacons should be wearing Clerical attire when functioning in their role outside of their secular employment.

Amen, John.

-Deacon Chuck

Only if the deacon can be easily distinguished from a priest.

In our diocese, the deacons are to wear grey shirts while performing their ministry, and the priests are to wear black, per our bishop.

I was so looking forward to reading this article, until the big fumble of the first paragraph: “The singular issue of ad Orientem worship in the Roman Liturgy unfortunately overshadowed his talk.”

“Unfortunately”? No, Father… Having the priest lead the people in facing the Lord would be the easiest and biggest improvement that could be made to the way the Ordinary Form is typically celebrated. Deacons are great, but why drive a wedge between your readers in the opening paragraph?

The issue of Ad Orientem is seen by many of us as one of many gems found in the the wealth of liturgy the Church possesses. That it is a wedge in some minds decries the basic intent of all true liturgy, does it not? Is not the most basic, most holy, most traditional orientation we are called to in the Eucharist is to the true Body of Christ? And was not the prayer of our Lord in the upper room, prior to His passion, that His followers be one as He and the Father are one? Did Christ say we MUST face a certain direction? Is not the Presence of Christ also in His Body, the people of God?

Harvey B: Thank you for your response. I pray that that particular line did not keep you from hopefully enjoying the rest of my article. I am an advocate for Ad Orientem worship. I celebrate both forms of the Roman Rite, and I an hopeful that the discussion involving this central issue will continue in the public sphere.

We must admit, however, that there was certainly more to Cardinal Sarah’s talk than Ad Orientem worship. He central thesis was the ongoing reform since the Second Vatican Council. It was my intention to merely demonstrate, using his talk, that the conversation was indeed still ongoing. I hope this clarifies my intention. Thanks again for reading my article!

Fair enough. Sorry if my tone was too critical — I love Cardinal Sarah and his attempt to “re-orient” the posture at Mass, and I guess the word “unfortunately” jumped out at me.

Thank you Father. We needed this.