26th Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 1, 2017

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/100117.cfm

Ez. 18:25-28; Ps. 25:4-5, 6-7, 8-9; Phil. 2:1-(5)11; Mt. 21:28-32

Religion and Faith

Often the Gospels describe a confrontation between Jesus and certain groups or classes. Generally, those groups represented the religious leadership of Israel. Unfortunately, they seem to have had a hard time accepting Jesus and his message.

Today’s Gospel describes one of those confrontations. When the chief priests and the elders questioned Jesus about his authority he responded with a story and a warning.

The elder son symbolized the religious leaders who rejected Jesus and, in wider sense, the whole nation. The concern of those leaders was more with religion as they understood it than with faith in Jesus. Like the elder son their willingness “to go into the vineyard” was not sincere.

The younger son symbolized people who were despised by the religious leaders: tax collectors, prostitutes, and, in a wider sense, Gentiles. They were people not interested in religion as practiced by the religious leaders. They came to accept Jesus in faith and effectively “entered the vineyard.”

In the latter part of the Gospel passage Jesus tells the chief priests and the elders their religious practices are useless without faith. Jesus tells them tax collectors and prostitutes will enter the kingdom of God before them because, in spite of what they had seen and heard, they did not repent and believe.

This Gospel passage points out something very important about faith and religion. Sometimes those terms (faith and religion) are taken to be roughly synonymous. But they are not at all the same. The difference between them be seen more clearly if we speak of religious practices rather than religion.

There is of a close relationship between religious practice and faith. Religious practices have to be based on and animated by faith. Faith has to be lived out in the context of authentic religious practices. One without the other is defective.

The fault Jesus found with the chief priests and elders was they had religion without faith. Unfortunately, that remains a danger for all of us, to have religions without real faith. There are various ways in which people can do that. Example: Some people seem to believe mere initiation into a religious group and simple observance of certain rites are enough to achieve salvation. Concretely, this is the kind of person sometimes described as “the hatched, matched, and dispatched Catholic”—i.e., a person who identifies as Catholic, is baptized, feels the need to be married in church, wants to be buried in church, and goes to church at Christmas and perhaps at Easter. But that’s about it. They recognize few, if any, further demands of faith.

On another level, persons having religion without faith tend to treat rites and symbols as magical rather than truly religious. So conceived, the symbols do not lead to the mystery of God, but substitute for it. Magic and faith are confused.

On the ethical level religion without faith sees only a system of rules and regulations to be observed in a legalistic way, not unlike the Pharisees of Jesus’ time.

The Lord calls us to more than religion/religious practices. We are called to a living faith whereby we enter into a living relationship with God. That involves something more than adherence to a system of ideas or obedience to a collection of rules or the practice of certain rites. It requires an authentic desire to follow Christ, whatever the costs.

That desire is to be confirmed by fidelity. Fidelity shows the desire to be sincere and to involve a deep intention in contrast to fleeting emotion. It is relatively easy to show good will from time to time. The real challenge is to be consistent in manifesting one’s faith commitment in the concrete circumstances of one’s everyday life.

__________

27th Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 8, 2017

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/100817.cfm

Is. 5:1-7; Ps. 80:9, 12, 13-14, 15-16, 19-20; Phil. 4:6-9; Mt. 21:33-43

Care of the Vineyard

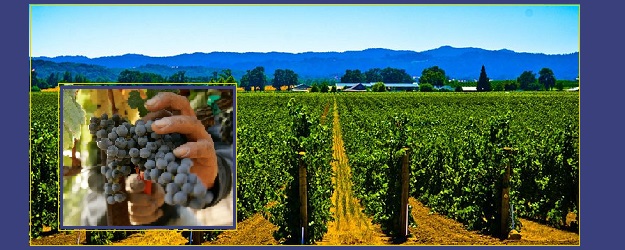

Like all good teachers, Jesus often used images easily understood by his listeners. In today’s Gospel, he uses the image of a vineyard. The Gospel parable is built upon the vineyard song of Isaiah. At the end of the song, the friend and his vineyard are identified as Yahweh and Israel.

The vineyard is carefully prepared and well cared for. The outcome, however, is one of bitter disappointment. The parable symbolizes the fact that the people of Israel were not faithful to the covenant Yahweh made with them. In the Gospel parable, Israel remains God’s people, and Yahweh is the absentee landlord. God’s covenant was an offer of salvation, and that offer is open to all people. God invites everyone into the kingdom.

When we reflect on this parable of the vineyard, a question naturally arises. How could those tenants be so ungrateful? How could they react in such a selfish, unjust, and, eventually, murderous way? We tend to interpret the parable as primarily reflecting the refusal of Jewish leaders of that time to accept Jesus as the Messiah.

But we need to look beyond that historical event. It helps to ask what the parable means for us. The vineyard can also be seen as something entrusted to our care. How do we care for the vineyard? What do we return to the owner? What are some of the obstacles that keep us from responding as we should?

Whether we have been conscious of it or not, we have all been objects of special care, of God’s loving providence. Unfortunately, we have often enough failed to yield the expected crop of grapes. We have all been given use of a well-prepared vineyard, as described in this Gospel passage and, often, we have failed to return the owner’s share of the grapes.

What is it that keeps us from responding as we should? There are various obstacles that hinder or prevent us from encountering God, and responding as we should. An obstacle we all have to overcome is self-centeredness. The more we are wrapped up in ourselves, the more isolated we become from God, and the less likely we are to encounter God in our lives. It is as though Jesus, encountering a completely self-centered person, is led to say: “This person is so full of self, there is no room for me.” If we don’t encounter God, how can we possibly respond to God’s invitation?

Self-centeredness is closely aligned with sin. Sin can be understood as a negative response to God’s invitation. Sin separates us from God. Traditionally, we speak of sin as an offense against God. If we think about it, we have to realize that is not exactly the case, not the best way to describe what is involved in sin.

Strictly speaking, God is beyond being offended or hurt in the ordinary sense of those terms. It seems more accurate to see sin as a barrier which makes it impossible for Jesus to enter into our lives, and for us to encounter God in a life-giving way. Another physical image that is helpful in understanding what sin involves is to think of sin as a hard crust on the soul, which renders it impervious to God’s grace.

There is another obstacle to encountering God, and responding to God’s invitation, which is more subtle but, nonetheless, effective. It is indifference, lack of care or concern about whether we encounter God or not. It consists in being oblivious to the ways of encountering God because we are preoccupied with so many other things. We miss his invitations.

The Cathedral of Chartres in France is world-renowned for its architecture, for the beauty of its design and workmanship. One of the carved stone figures high up in an arch of that cathedral depicts God holding Adam ever so tenderly in his lap. Adam is asleep with his chin on his chest, and his arms and legs drawn up closely to his body, almost in a fetal position. God is looking at him with deep care and compassion, as though he longed for his grace to awaken Adam from his sleep and, thus, to become aware of the one whose arms hold him, and of how much he is loved.

What a beautiful image! It suggests in a symbolic way the beautiful and consoling truth that God holds each and every one of us in a longing gaze, seeking to awaken us from our sleep of preoccupation and self-absorption, so that we might encounter him and realize who it is that loves us.

__________

28th Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 15, 2017

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/101517.cfm

Is. 25:6-10a; Ps. 23:1-3a, 3b-4, 5, 6; Phil. 4:12-14, 19-20; Mt. 22:1-(10)14

Come to the Wedding Feast

The Gospels tell of many instances of conflict between Jesus and the religious leaders of Israel. In the Gospels, we get a clear picture of how that conflict, between Jesus and the chief priests and elders, grew progressively stronger and sharper until it ended in Jesus’ death. In various ways, Jesus challenged those religious leaders. He told them their idea of God, and what God wanted, was flawed. He invited them to recognize him as the Messiah, and to accept his message. Sometimes, as in today’s Gospel, he did that by means of a parable.

According to some scripture scholars, the parable in today’s Gospel is actually a combination of two parables, originally spoken on different occasions. The theory is aimed at explaining a difficulty presented by a simple reading of the parable. The difficulty is this: The king eventually has his servants invite people to the wedding feast right off the streets. Then, he expects them to be dressed for the occasion, and excludes them if they are not appropriately dressed. That doesn’t seem fair or reasonable. Thus, the theory of two distinct parables, each aimed at illustrating a different truth.

The theory is a good one. There are two distinct messages or truths conveyed by the parable. The first is the universality of God’s call to salvation. Everyone is eventually invited to the feast. Everyone is called to salvation. The invited guests who refused to come symbolize the Israelites, who failed to accept Jesus as the Messiah. Those invited later (as the Gospel puts it “anyone you come upon”) symbolize the Gentiles, i.e., all people.

The second truth conveyed by the parable is that God’s call requires a specific response. This response involves accepting Jesus as savior, and includes a conversion of heart or, in the symbolism of the parable, putting on a wedding garment.

Someone has suggested that parables are like glass. Some are windows through which we gain a particular perspective on our world. Some are like a mirror in which we are invited to see a reflection of ourselves. Today’s parable is a mirror.

If we look into this mirror, how do we see ourselves? How do we respond to the invitation that the Lord extends to us to come and share the banquet? Obviously, we ourselves have given a positive response. Otherwise, we would not be here. The real question for us is, what is the quality of our response? Have we allowed our response to become less generous, half-hearted, and unenthusiastic? In answering these questions, it might be helpful to note a few other facts suggested by the parable.

First, the parable suggests that God’s invitation is to a feast that is joyful, like a wedding feast. God’s invitation is to joy. But the Gospels also tell us that following Christ involves sacrifice. We have Jesus’ own words: “If anyone would be my disciple, let him take up his cross and follow me.” We are faced with a paradox. Sacrifice/suffering is an essential element of the Christian life. Our faith is in a suffering Savior. We are encouraged to join our suffering to his. Where then is the joy?

The paradox is real. The solution is not either/or. The solution is: both/and; sorrow and joy, tears and laughter, dying and rising intertwined. Those things are part of the fabric of life. Cardinal Newman suggested “joy is the child of sorrow.” Our Christian belief and practice illustrate the truth of that phrase. If we truly join ourselves to Christ in his suffering and death, we will come with him to the joy of the resurrection and our redemption from sin.

Secondly, the parable suggests that the things that lead people to ignore the invitation are not bad in themselves. One man went to his estate, another to his business, a third to fulfill domestic obligations. We are reminded that we can become so preoccupied with things in this world, even legitimate things, that we neglect things beyond this world. We can listen so intently to the claims of this world that we fail to hear the invitation of Christ. As someone put it, a person can be so busy making a living that they fail to make a life.

Finally, the parable reminds us that God’s invitation is a gift, a grace. Those who were gathered in from the byways had no claim on the king. We, too, have no claim on the King. We do not merit God’s invitation. It is a grace God lovingly offers. Generally, to refuse an invitation is a matter of discourtesy. To refuse the Lord’s invitation reflects a serious lack of faith and generosity.

As we continue our Eucharist, let us pray for a strengthening of our faith, that our faith be a lively faith that prompts us to respond generously to God’s call.

_________

29th Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 22, 2017

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/102217.cfm

Is. 45:1, 4-6; Ps. 96:1, 3, 4-5, 7-8, 9-10; 1 Thes. 1:1-5b; Mt. 22:15-21

Beware of Becoming an Unconscious Pharisee

The Pharisees are mentioned frequently in the Gospels. They played a significant role in the public life of Jesus. What we know of them leads us to have a very negative opinion of them. We see them as legalistic hypocrites, blind to Jesus and his message. We see them becoming increasingly hostile to Jesus, and eventually seeking to destroy him. They are often presented as questioning Jesus, trying to provoke a response that will discredit him.

Specifically, in today’s Gospel, the Pharisees propose a dilemma designed to get Jesus into trouble, no matter which alternative he chooses. If Jesus said it was lawful to pay the tax, he would be in trouble with the Jewish people. If he said the tax should not be paid, he would be in trouble with the Roman authorities. As he often did, Jesus responded with a question. In doing so, he escaped the dilemma and raised the issue to a new level.

Although he was often in conflict with the Pharisees, Jesus recognized their role as teachers in Israel. He told people, “Do as they say; not as they do!” The Jewish people were people of the law as handed down by Moses. The Pharisees were the interpreters and guardians of the law. In fact, it was to their credit that they were the ones largely responsible for sustaining fidelity to the Law of Moses in Israel.

Jesus was sharply critical of the religion of the Pharisees. They often turned life-giving principles into regulations that suffocated and condemned. Over time, the great principles of the Law were broken down into literally thousands of rules and regulations. The Pharisees believed salvation was attained through scrupulous observance of those rules and regulations.

Rules and regulations have their place, their importance. But to see religion as consisting only in rules and regulations holds two dangers. First, following the rules scrupulously can lead to presumption, to thinking we earn God’s grace through our own efforts, that we save ourselves. Secondly, failing to follow the rules, while believing them to be our salvation, can lead to scrupulosity.

The Pharisees thought they knew exactly what God wanted of them. When Jesus told them they didn’t have it right, they simply refused to believe him. In fact, they turned strongly against him and his message. The Pharisees were dedicated legalists. For them, religion consisted in careful observance of every detail of the Law. At the same time, they were deeply religious in the sense of being desperately earnest about the practice of religion; but religion as they understood it.

Much of the behavior of the Pharisees was self-serving. Deeds were performed to be seen and admired. Reflection on their behavior has resulted in the term “Pharisee” becoming a synonym for “hypocrite.” The problem of the Pharisees was not so much a lack of faith, as a lack of humility, humility that would allow them to admit they could be wrong. They had lost the capacity for self-criticism. Lack of humility is often accompanied by stubbornness. Thus, the Pharisees became fixed in their opposition to Jesus, which then became stronger and stronger.

Having said all that about the Pharisees, I still like to think of them as affording us a good example in a negative way. We must be careful not to out-Pharisee the Pharisees, i.e., not to think of ourselves as incapable of making the same mistakes they did. We can learn from them not to think we understand so perfectly what God wants of us that we never have to make any adjustment in our thinking. To put it a bit differently, the valuable lesson we can learn from the Pharisees is that they needed to change their minds, to be converted. There is a sense in which we, too, need to be converted, i.e., converted in the sense of being continuously in a process of turning away from sin, and turning to the Lord.

From time to time, the Gospels describe Jesus as challenging the Pharisees in very strong language. It helps to remember Jesus also found it necessary to challenge his close followers. We can find 17 places in the Gospels when Jesus asked his disciples: “Are you still without understanding?” It is not that the disciples were dull or of low intelligence. The real challenge for Jesus is not one of a lack of intelligence among his disciples, but for them to be willing to give up an old vision, and accept a new one. The challenge Jesus presents to anyone who wants to be his follower is not so much a matter of understanding, as a matter of radical faith, and profound trust in Jesus as Son of God, and our Savior.

_________

30th Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 29, 2017

Readings: http://usccb.org/bible/readings/102917.cfm

Ex. 22:20-26; Ps. 18:2-3, 3-4, 47, 51; 1 Thes. 1:5c-10; Mt. 22:34-40

The Pharisee’s Great Question

A Pharisee asked Jesus, “Teacher, what commandment in the law is the greatest?” Jesus replied by stating what we call the “great commandments of charity.” In that reply, Jesus expressed a great truth. All great truths involve a kind of paradox. They can be expressed in a short formula, but then volumes are written trying to make explicit what they mean. The great truth expressed by the “commandments of charity” can be stated briefly: love God and love your neighbor. But, there is much commentary explaining what those two commandments involve.

What does it mean to love God and to love one’s neighbor? How do we know, if and when, we are doing that? We have heard so much about the love of God and the love of neighbor that we think we know the answer to these questions. But on reflection, we realize the answer is not easy.

“Love” is one of those words that has become overloaded with meanings. It is used so much, and in so many different ways, that it is not at all easy to say exactly, and in simple terms, what it means. For example, a man may say: “I love my wife. I love my Toyota. I love my children. I love my job.” Clearly, love takes on a different meaning in each of those cases. And more, love can mean “zero” when we play tennis, and we can even find the word “love” in the title of an X-rated movie. Where do love of God and love of neighbor fit in?

Among the many definitions or descriptions of love, there are two which are fairly simple and helpful in talking about the “commandments of charity.” The first was suggested centuries ago by St. Thomas Aquinas. He said: “To love anyone is nothing else than to wish that person well, to want what is good for them.”

Isn’t that the case when parents truly love their children? They may not always give them what they want, but they always want to give them what they truly believe is good for them. And, isn’t it also true when there is genuine love between spouses and among friends. That reality is reflected in the phrase “tough love.” That definition of love has the advantage of distinguishing real love from feelings or emotions that may accompany love, but are not essential. It enables us to see how we can truly love our neighbor without necessarily liking him or her. Over the years, I have met people I don’t really like, but I can still fulfill the commandment of love for them, because I wish them well, and I want what is good for them.

While St. Thomas’ definition is helpful when speaking of love of neighbor, it doesn’t work as well when we speak of love of God. We can say “God loves us” in that God wants what is good for us. In fact, God has shown his love in giving us everything we have and, especially, his own Son for our salvation. But it makes little sense to say we love God because we want what is good for God.

Thus, a second definition of love is helpful, i.e., to define love as a union of wills. We love God when we join our will to his, when we want what God wants, when we try our best to live according to God’s will. If we turn our heart and soul and mind to the task of doing God’s will, we are loving God.

Two further questions come to mind when we reflect on what we call the “commandments of love.” First, how do they relate to the Ten Commandments? Some people may protest that the Ten Commandments are too negative, usually stating a prohibition: “thou shall not!” But the two sets of commandments are perfectly compatible, in fact, complementary. The Ten Commandments simply make explicit what a person must do if they truly love God and neighbor. It is easy to say “I love God” and “I love my neighbor.” It is a great challenge to do consistently what love requires if it is to be authentic.

The second question is this: How can love be commanded? No doubt, we would find it strange if someone said to us: “I command you to love me!” To understand how love can be commanded, it helps to get beyond thinking of love as simply a feeling, an emotion. True love usually has an emotional component but, in essence, love is a function of the will. To love God means that we join, or conform, our will to his. To love our neighbor, means we will our neighbor’s good. Love in that sense can be, and is, demanded of us.

Thanks for the spiritual enlightenment. The best homily is the homily prepared on knees.