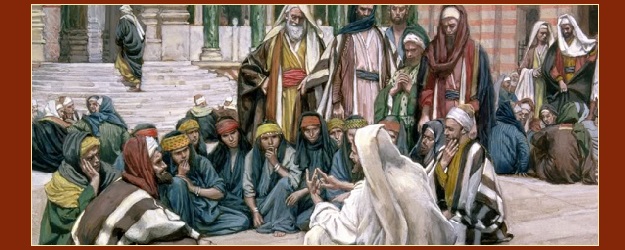

Christ Preaching Outside the Temple by Tissot

(First published in “Spirituality,” July/August 2013. Dublin: Dominican Publications.)

Since the Second Vatican Council, Catholics have come to a better appreciation of the full humanity of Jesus, which was always a part of Church dogma. The sixteenth century Counter-Reformation led Catholics to emphasize Jesus’ divinity, along with devotion to Mary as the Mother of God, in response to those reformers who questioned his full divinity. With the Vatican Council in the 1960s came less polemics, and the recovery of something lost during the Counter-Reformation, an appreciation of Jesus’ full humanity. This was aided by a return to scriptural sources, that gave a breath of new life to Catholic theology.

The Epistle to the Hebrews gives strong expression to Jesus’ humanity. “He had to become like his brethren in every respect. Because he himself was tested by what he suffered, he is able to help those who are tested (2:17f). Although he was a Son, he learned obedience by what he suffered (5:8; cf. Mark 14:36).” Luke adds that “Jesus advanced in wisdom and years, and in divine and human favor” (2:52). Theologians have suggested that although at the depth of his consciousness, Jesus was aware of his special relationship to the Father, he was not able to draw on this awareness for any knowledge.

It took the Apostolic age, and then centuries after, to clarify the full divinity of Jesus. Our challenge now is to work back to understanding his full humanity. In the thirty-five or so years from Jesus’ death to the writing of Mark, the oral tradition had greatly embellished the story of Jesus’ life. In approaching even this earliest gospel, we have the task of identifying the faith statements of the early church, which were likely added to the tradition during their Eucharistic celebration of the Good News of Jesus Christ. These embellishments sustained them through times of persecution, but obscured his full humanity (4:41; 6:50). Our purpose here is to work back to the Jesus who was known to his contemporaries, and who had emptied himself of divinity to share fully in our human experience and suffering. In this way, he truly became, according to the Epistles of St. Paul to the Hebrews, the “pioneer” and “forerunner” of our salvation.

To his contemporaries, Jesus must have seemed quite ordinary. His relatives wanted to take him away, thinking him crazy (Mark 3:21, 31). His townsfolk in Nazareth tried to throw him over a cliff (Luke 4:29). The Jewish leaders thought him a blasphemer (Mark 2:7). Only the few who saw him with the eyes of faith, in the Spirit, could be cured by him (Mark 2:5; 5:34; 10:52). Even to the end of his life, he tried, in futility, to convince his disciples to see him at a deeper level. Peter wanted Jesus to start a popular revolution for which Peter received the rebuke: “Get behind me, Satan”; this may indicate what was a temptation even for Jesus. He repeatedly grieved over the lack of faith (Mark 4:40 “no faith”) and the lack of understanding (Mark 4:13; 8:17-21; 6:52; 7:18; 9:19, 32; 10:38; 16:11, 14) displayed by his closest disciples. Jesus chided Mary Magdalene for her all-too-human understanding of whom Christ really was. He admonished her in the garden to not cling to him as he had not yet ascended to his Father (John 20:17). Then, he told his disciples that he must go so that the Spirit might come, all this in order to reveal himself to them at a deeper level than they had known him before. (John 16:7-25).

The Baptism

To recover a sense of Jesus’ full humanity, we will look mainly at Mark’s Gospel, with a critical eye for detail. According to Mark, only Jesus hears his vocation call, just after his baptism by John. In Luke, Jesus hears this call later, “while he was praying” (Luke 3:21f). But the Gospels of Matthew and John have the Baptist recognizing Jesus already at his baptism. This doesn’t harmonize well with the Baptist later questioning who Jesus was (Matt. 11:2f) and continuing to baptize though this caused tension with Jesus’ disciples (John 3:25f). In contrast, Mark has Jesus delaying his ministry until the Baptist had been imprisoned (Mark 1:14).

During centuries of regarding the Gospels as literally dictated by God, the tendency has been to harmonize discrepancies, and to safeguard the historical accuracy of every statement. Today, we see the Gospels, rather, as saving truth—through ruminations from various faith communities in the early church, including the perspectives of four different human authors. In trying to rediscover the human Jesus, we are less compelled to gloss over discrepancies. We search for reasonable explanations why the story was retold as it was, or why the facts were embellished.

Historical studies have revealed that the followers of John continued as a separate movement, even into second century Egypt. This would warrant the insistence, most evident in John’s gospel, that the Baptist himself testified to Jesus’ superior status, even from the start. John’s whole Gospel portrays Jesus walking as a God among men, particularly in the passion narrative where Jesus is completely in control. The word “suffer” never occurs in John’s gospel. This is very different from Mark where Jesus seems alone in his ministry, the consolation of the Father breaking through only at one moment of transfiguration (9:2; the same word is used for our “transformation” in 2 Cor 3:18). In Mark, Jesus’ disciples recognize the import of his life and suffering only after his death, with the rending of the temple veil, and recognition by the pagan centurion: “truly this man was the Son of God” (Mark 15:39). In light of this, Cardinal Carlos Martini sees Mark’s gospel as “a warning and a consolation to followers. It is necessary to take up one’s cross before being recognized by God” (Mark 8:34; 10:29f).

The Earthly Jesus

Jesus’ full humanity is evidenced by the array of human feelings he exhibited: pity and compassion (Mark 1:41; Luke 13:34f); anger (Mark 3:5; 10:14; and, desolation (Mark 14:33; 15:34). The lack of understanding from the crowds, and even from his own disciples, surprised and distressed Jesus (Mark 8:12, 17-21). He thought the kingdom was imminent (9:1; 13:30, 32), in continuity with the Baptist, and the early Church (2 Pet 3:3-10). Detailed accounts of the future including a Gentile mission (Mark 13:10 v. Matt 10:5f) are likely from the early church.

Matthew and Luke place an elaborate testing of Jesus in the desert immediately after his Baptism, illustrating that Jesus overcame, in ways the Hebrew people failed, during their desert wanderings. Mark omits this, but indicates various tests throughout Jesus’ life, especially at the hands of the Jewish leaders, concerning his authority (2:6; 3:22; 8:11; 11:28), his interpretation of the Torah (2:16, 18, 24; 3:4, 6; 7:5; 12:18, 24), and, his attitude toward the Romans (12:14).

Not only after his baptism, but on a regular basis during his life, it is revealed that frequently Jesus prayed: “early in the morning, he went aside to pray” (Mark 1:35; 6:46; 14:35; Luke 6:12; 9:18, 28; 11:1). Like us, he needed to reflect on the concrete circumstances of his life, how things were going, and to seek inspiration from the Father amidst Jesus’ attempted mission to establish the expected Kingdom among the Jewish people. For the first eight chapters of Mark, Jesus seems confident that the Jewish authorities would recognize, in his presence and works, the advent of the Messianic Age. He pleads for their understanding: “If it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come to you” (Mark 3:23; Luke 11:20). But he found these authorities wanting compared to the teachability of mere children (cf. Mark 10:15).

From the time he cures the Syrophoenician woman (Mark 7:26-29), his attitude seems to change. The Jewish leaders had not recognized in him the advent of the Messianic Age, or of a more spiritual kingdom of God in their midst. Even his closest disciples showed little comprehension of the nature of his mission (Matt 16:13-17). And when Peter showed insight beyond the others, it was without understanding the nature of the kingdom (Matt 16:22f).

The danger to Jesus’ life had been clear (Mark 3:6; 11:18), but three “passion predictions” (Mark 8:31; 9:31; 10:33) came after a turning point, and were likely embellished by the Church to cover embarrassment at following an ignominiously, crucified leader. It was because of this embarrassment that Luke emphasizes that it was “according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” (Acts 2:23; 4:28; 5:38f; Luke 9:51; 24:26) that Jesus had been crucified.

Conclusion

During four centuries of Counter-Reformation theology, two issues contributed significantly to obscuring Jesus’ full humanity: the beatific vision, and an “infinite debt” owed to the Father for human sinfulness. Modern scripture studies have suggested a different understanding of these issues. His sacrifice (hilasterion) is now better understood as impacting us—“expiation” rather than “propitiation” (NAB Rom 3:25). Jesus was demonstrating a merciful Father’s love (1 John 4:10) in emptying himself of his divinity, and becoming completely like us (Phil 2:7), to lead us on the way to life. And the mystery of his dual nature has been focused more on how Jesus was divine, with preservation of his full humanity. This role of Jesus is explained in Hebrews:

Let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the sake of the joy that was set before him endured the cross, disregarding its shame, and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God. Consider him who endured such hostility against himself from sinners, so that you may not grow weary or lose heart. In your struggle against sin you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood (12.1-4).

Jesus reinforces this understanding in his response to the women of Jerusalem on the road to Calvary: “Weep not for me, but for yourselves and for your children” (Luke 23:28). He does not want their pity but their faithfulness in following him, as Christians. We find encouragement in finding him alongside us on life’s paths, “for my yoke is easy and my burden light” (Matt 11:30). The more like us he became, the more encouragement he brings to us in our sufferings. As Paul summarizes the matter: “Suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us” (Rom 5:3-5). Or again “We suffer with him so that we may also be glorified with him” (Rom 8:17). It is the fully human Jesus, who during his earthly life, suffered as we do, and then left us his Spirit, who in Mark 8:34, Jesus bids us to take up our cross and follow him.

Thank you so much

I used to receive you’re Magazine, and loved it!