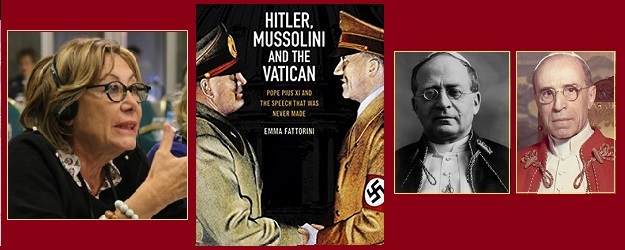

Emma Fattorini, her book, and Popes Pius XI and Pius XII

Hitler, Mussolini, and the Vatican: Pope Pius XI and the Speech That Was Never Made is an English translation published in 2011 of a book first published in 2007 by Emma Fattorini, professor of Modern History at the University of Rome.

This is a 2011 translation of a book first published in 2007 by Emma Fattorini, professor of Modern History at the University of Rome. Interestingly, although not directly related to this book, Fattorini is also a politician. She was elected to the Italian Senate in 2013, six years after the book was originally published, and two years after this translation appeared.

Based on Professor Fattorini’s studies of documents from the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922-1939), the book gives vivid glimpses into the many ways Pope Pius XI was thwarted in his growing intention at the end of his life to abandon all hope in diplomatic solutions, and to speak out decisively against the evils of anti-semitism. Throughout his papacy, Pius XI was frustrated not only by rulers of governments who were hostile to the Catholic Church, but also by the Catholic press, by many clergy up to the highest levels of the hierarchy, and even by some of his closest aides, including his Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli.

The book raises many questions about the motives of those who worked against Pius XI, especially the ones who were supposedly working for him. Before I read it, I realized in an abstract way that any pope must be surrounded by intrigues, like any ruler surrounded by scheming courtiers, but this book turned my abstract idea into a concretely fleshed-out reality, naming names, and describing personalities.

What’s a “Secret” Archive Anyway?

Fattorini’s research was made possible when on July 2, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI authorized the opening of the Vatican archives for the pontificate of Pope Pius XI, who reigned during the years leading up to World War II, while Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin rose to power. Researchers were then permitted to consult all the documents of the period “kept in the different series of archives of the Holy See, primarily in the Vatican Secret Archives, and the Archive of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State (formerly the Congregation of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs).” The materials included the diaries of Eugenio Pacelli, who became Secretary of State in 1930. After Pope Pius XI’s death in 1939, Pacelli became the camerlengo, the chamberlain who handles the transition after the death of a pope, and the election of another. He was elected pope at the conclave and took the name Pius XII .

Much sensationalist ado is made by Dan Brown (author of potboilers, such as the Da Vinci Code) and by other like-minded writers about the Vatican’s Secret Archives, who manage to give the word “secret” an unwarranted sinister twist. The reality is more prosaic. The name of the repository in Latin is Archivum Secretum Vaticanum, and, as the Vatican website tells us, secretum simply means private. The current pope alone decides when to make the documents of any previous papacy available for research.

Why Review This Book?

What first drew me to volunteer to review Hitler, Mussolini, and the Vatican was my disdain for the sensationalist book, Hitler’s Pope, published by British journalist and academic, John Cornwell, in 2008. Cornwell claimed he had been requested by the Church to research the papacy of Pope Pius XII. He had suspiciously enough also made similar claims that he had been requested by the Church to research the death of Pope John Paul I in an earlier book, even though it confounds common sense to believe that a seminary dropout, who was an outspoken critic of the Church, would be drafted for such a task in either case.

Because of the title of Fattorini’s book—Hitler, Mussolini, and the Vatican—I thought perhaps this book might be of the same type as Cornwell’s, which one other reputable reviewer called “a tissue of lies,” and if need be, I was ready to try to refute it. When I started to read it, even though a blurb from John Cornwell is on the dust jacket, I realized I was wrong. Cornwell’s blurb is subdued, and accurately describes the book as a scholarly work.

The Lateran Pacts, the Concordat, and Pope Pius XI’s Last Acts

Part of this book concerns the central event of Pope Pius XI’s pontificate, which occurred on February 11, 1929, when the Vatican signed agreements with the Mussolini government that resolved the “Italian question”—about the status of the pope after the unification of Italy in the nineteenth century, and the confiscation of the Papal States.

In 1861, the Papal states had been annexed into the new nation of Italy. The popes during the ensuing half a century, or so, had reacted to the erosion of Catholic influence, and the loss of territory, by refusing to become Italian citizens. They viewed themselves as prisoners of the Vatican, and for a long time forbade Catholics to participate in the political doings of the new nation, which was hostile to the Catholic faith.

Part of the “Italian question” was how to define the scope of the Church in unified Italy, along with determining the amount of reimbursement the Catholic Church should receive for its confiscated lands and buildings. The Lateran pacts included a concordat, an agreement that defined relations between the Church and the Mussolini government.

With the pacts, the Holy See renounced all claims to temporal power—to emphasize the Church’s renunciation of any claims to reign in the temporal sphere. The Vatican City State was created as a sovereign territory under the sole rule of the Holy See. Pius XI insisted on preserving only the minimum amount of territory, and accepted a lower amount of compensation than had been offered in earlier negotiations, in order to maintain the Church’s independence.

It’s refreshing to read Fattorini’s interpretations of the papacy of Pius XI, especially since her views also stand in great contrast to another later sensationally-written book, published in 2014, by Brown Professor David Israel Kertzer titled: The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. Kertzer’s potboiler became a blockbuster hit, and won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize.

Perhaps in a bid for the enormous fame that Cornwell achieved with Hitler’s Pope, Kertzer went far beyond scholarly detachment when he argued his own opinion that the Vatican’s agreement with Mussolini’s government in the Lateran Pacts was a deal Pius XI made with the devil to achieve the pope’s dastardly craving for power.

Using the same set of documented facts, Fattorini more appropriately portrays Pope Pius XI as a strong-willed and deeply religious man, who originally saw Mussolini’s willingness to restore Catholicism as the religion of the Italian nation as a boon. Children would be again taught the faith in schools, and crucifixes would again hang in every classroom. Gradually, in the ten years that followed the pacts, Pope Pius XI became more and more disillusioned by how Mussolini’s government betrayed the concordat, and enacted anti-Jewish laws similar to those of the Nazis to whom the Fascists were aligned.

The book’s main revelation for me was the close relationship between the blunt, outspoken Achille Ratti, as Pope Pius XI, and the deftly diplomatic Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII.

In 1938, and the beginning of 1939, Pope Pius XI was weakened by heart disease which would eventually kill him, but he kept working even when bedridden.

The 10th anniversary of the Lateran Pacts was approaching. He’d called a conclave of Italian bishops for the occasion of the anniversary, and he worked doggedly on a speech he wanted to give at the event. Afraid that he might not be strong enough to attend, he had sent the speech to the Vatican’s secret printer to prepare copies to be handed out at the conclave.

He died the day before he was supposed to give the speech. Astonishingly, under the authority he had as camerlengo, Eugenio Pacelli had every copy destroyed after Pius XI’s death, and the speech that was so close to the dying pope’s heart became the “speech that was never given,” which became this book’s title, as well. It joined an encyclical that also never saw the light of day, because of the machinations of the anti-semitic head of the Jesuit order.

The Encyclical That Was Never Released

Another striking instance of how the pope’s desires were blocked also occurred in the months before his death. In June 22, 1938, Pius XI asked an American Jesuit, Father John LaFarge, to collaborate with him on a new encyclical that would go far beyond any previous papal document in explicitly condemning anti-semitism. LaFarge’s superior, Wlodimir Ledóchowski, Superior General of the Society of Jesus, who was anti-semitic himself, assigned two other Jesuits to work on the project with LaFarge, one a German, and the other French.

On October 1, before LaFarge returned to the U.S., he gave Ledóchowski the text of the encyclical. But the pope only received the text four months later, and only after he made repeated requests. Twenty days after he finally received the text, the pope died. Instead of delivering the text to the pope, Ledóchowski had given it to a Father Rosa to revise it, even though Father Rosa had been writing articles for Civiltà Catholica, a periodical published by the Jesuits in Rome, concerning the Jews, and the views he expressed were so harsh, they were used by fascist propagandists in defending Mussolini’s racial laws.

Style and Substance

Maybe because it is a scholarly work, and maybe also because of differences between the loquaciousness of Italian versus a more-terse English writing style, this book is not easy to read. I found it repetitive, and it is sometimes difficult to figure out what the author is trying to say. However, this book is important enough to not let it pass without recognition, and I hope to give the book its due, after having let it slip from public awareness for so long a time.

Of course, we all must wonder what motivated Eugenio Pacelli to destroy the speech that his predecessor pope had so devotedly created. The documents Fattorini quoted can tell us what was done, and where, and sometimes how, but they cannot definitively tell us why, because the “why” is nowhere written down. Or sometimes the “why” is documented, but the truth of the given reason is disbelieved.

Fattorini makes some tentative explanations of her own. Her personal style seems to rely on insinuation more than direct statements, when she writes about what the details mean. And she contradicts herself.

Here is an example from one paragraph in her Preface. First she notes that Pacelli had solid reasons to fear a break with the Fascists, and by extension, the Nazis: “The camerlengo, soon to be pope himself, had solid reasons to fear should the conclave be conducted with the Church openly defying Mussolini.” And she writes that it would have been surprising if he had made sure the document was circulated. “Indeed, it would have been far more surprising if Pacelli, rather than suppressing the address, had made sure that it was circulated.”

But then she wonders at the speed with which Pacelli got rid of the address. “And yet one cannot help but wonder at the diligence and speed with which he decided to deny the last wishes of the pope.”

Again, on the next page, she seems to agree with what Pacelli did, when she writes that the documents from “the last years of Ratti’s papacy also add new elements to the debate and confirm Pacelli’s prudent approach.”

Then she follows with “Who can deny, without the benefit of hindsight, that Pacelli’s prudence did have its ‘justifications’?”

But she weakens that statement again when she writes about how “we lament that the spirit of Pius XI, at the end of his life, did not live on in his successor …”

So which is it, Professor Fattorini? Was Pacelli justified in destroying the speech the dying pope was preparing for the conclave? Or should he have gone ahead and distributed it in “the spirit of Pius XI”?

Reading between the vacillating lines, my guess is she actually wants to assert that Eugenio Pacelli had justifiable motives in his destruction of Pope Pius XI’s last speech, but tries to soften her words to avoid being labeled a papal apologist by scholars who believe otherwise.

Good Questions

The actual truth behind Pacelli’s actions probably does lie in his famously diplomatic temperament. He often suggested to Pipe Pius XI, on other occasions, that he should tone down what he had written. My own inexpert impression is that Pacelli hoped to avoid the split he feared would happen if the speech was given, and wanted to avoid the crackdown on Catholics that would predictably result.

Why did Eugenio Pacelli use his power as camerlengo to destroy all copies of the speech? He relied more on diplomacy than confrontation. He’d seen the horrifying retributions the Nazis took against anyone who spoke out against their regime. If it had been released posthumously, Pius XI’s speech would have almost inevitably resulted in a break with the Fascist regime, which would have certainly meant a break with the Nazi regime also.

Can Historical Research Answer Questions of Motives Without Bias?

In her preface, Fattorini made it clear what her intentions were, that she was not about to do a Cornwell-type hatchet job:

Only calm and balanced historical research can hope to transcend the temptation to fall either into the apologetic trap of those who would see Pius XII as the greatest saint of the twentieth century, or into the opposite one, depicting him as Hitler’s pope.

A weakness with relying on calm historical research to discern the reasons behind historical facts is that each researcher brings his or her biases into the interpretation of those facts.

Fattorini portrays Pope Pius XI’s agreement with the Mussolini government in the Lateran pacts as motivated by a desire to restore the Catholic faith to Italy, and she portrays his renunciation of diplomatic actions as coming from his growing spiritual transformation. To the acts of Eugenio Pacelli, she attributes benign motives of trying to avert catastrophes, even though she hints they may have come from his vacillating personality.

In contrast, after accessing the same documents from the same papacy, Professor David Kertzer, in his The Pope and Mussolini, attributed unmitigatedly evil intentions to Pius XI, and to Pacelli. Because Kertzer’s book is so widely celebrated, his negative spin on the facts is becoming the commonly accepted interpretation.

For that reason, I hope that bringing Fattorini’s interpretation forward, however belatedly, can perhaps help counter the way Kertzer has portrayed the same events in a damning light.

Ultimately, this contrast between the two scholars reacting to the same material pinpoints a problem with expecting that historical research can determine the real motives of the actions of anyone. None of the acts described were evil in themselves. It is hard to know whether they were evil in intention.

I find Fattorini’s benign interpretation convincing. But ultimately, those whose convictions don’t fall on one side or the other might be tempted to say that God only knows—which is my usual response to anyone’s claim to have secret knowledge of someone else’s real motives.

I spent some time studying the work of archbishop (later cardinal) Borgonini Duca.who negotiated the Lateran Treaty and was Apostolic Nuncio to Italy from 1929 to 1953. Pius XI was a holy man with good intentions. He also had an explosive temper and was hard to work for. Borgongini Duca had a good relationship with Mussolini and his cronies and would feedback gossip to the popes he worked for. Mussolini would confide that he was a faithful Catholic and it was known he confessed with some regularity to a Jesuit with fascist leanings. Bongongini Duca would also pass along gossip about how crazy Hitler and the Nazis were. The Italian Fascists liked to posture about being tough guys but the Nazis were the real deal and what the Fascists found on their visits to Germany frightened them.

There were people like Pacelli who legitimately feared what the Nazis would do to the Church and Catholics generally if Pius XI’s tough line was pursued. In hindsight we can see the thought of managing the Nazi’s was naive but at the time the correct course of action was not at all easy to discern. Also note that vestiges of the Papal States lasted until 1870 when Rome fell during the sessions of Vatican I.

Thank you Philadelphia

Any article about Pius XI should include the fact that his 1922 decree, “Crimen Solicitationis”, imposed a permanent silence on all information about child sex abuse.

It should be noted in context that Mussolini, despite his pretensions for Italian expansion was a rather poor ally of the Nazi’s. His military was quite ineffective in combat and he waited until 1940 to enter WW II. He lacked the astuteness of a Gen. Franco, whom he would have been well advised to emulate, by keeping his ambitions confined to Italy itself. Pius XII, as stated, was ever the diplomat when what was needed was a more assertive personage in the papacy. Apparently he learned from the experience as his actions condemning European communists after the war were notable and helped stop a red takeover in Italy and France. It would be difficult to question the motives of both pontiffs just as they are easily criticized in hindsight.

I think the weak point of the various books is that they are too papal and ignore the actions of the lay faithful, who are the first lines of the Church in the affairs of states. In Germany, the Catholics heroically worked to keep Hitler from power. The Catholic Party in Weimer Germany put aside serious disagreements (such as abortion law) and formed a coalition with the Socialists and the Liberals to keep both the Nazis on the Right and the Communists on the Left out of government. When Von Papen, the leaders of the right wing of the Catholic Party, tried to put together a Nazi-Conservative-Catholic coalition, he was expelled from the Party. Sadly, in the end the Nazis entered government in a minority coalition with the conservative party without the support of the Catholics.

Dear Roseane: Thank you very much for greatly helping to restore balance to the interpretation of both Pius XI and Pius XII. They were both well-intended without question. May I humbly suggest using your great skills to set the record straight on the following: why neither of these well-intentioned Popes attempted to consecrate Russia to the Blessed Virgin Mary’s Immaculate Heart, with all the Bishops worldwide praying with the Pope for this to occur. This is what Mother Mary called for at Fatima in 1917, which would have prevented World War II, and overturned communism. This was Satan’s most serious threat till then, regarding the future of Christianity. Respectfully, Bill Bagatelas

Additional good reading could include The Myth of Hilter’s Pope by Rabbi David G. Dalin published in 2005.

From the review, I guess the author (Prof. Fattorini) doesn’t know what to choose between the good intention or bad intention: to get fame from a book with selling title.

I don’t think it’s Pacelli who destroyed the document. Just think: the Pope surrounded by many people (not only the camerlengo) & we learn recently: even a butler can betray his own master. Just because Pacelli was well known & he was a prominent figure, all finger pointed to him.