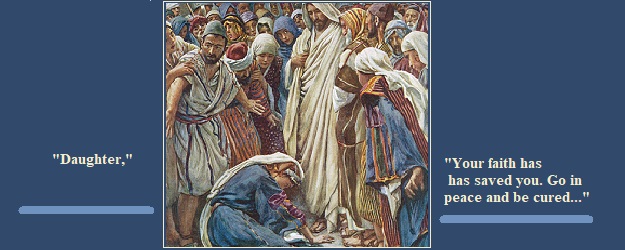

“The woman who touched the hem of his garment” by Harold Copping (1863-1932)

13th Sunday in Ordinary Time—July 1, 2018

Readings: Wis 1:13-15; 2:23-24 ● 2 Cor 8:7, 9, 13-15 ● Mk 5:21-43

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/070118.cfm

The gracious act of Christ, emptying himself for us.

In the liturgy today, we are given a word from the Book of Wisdom that faces, head on, the ultimate human question of death, and God’s relationship to it. The response could not be more blunt: “God did not make death.” What God does is create. He makes life and offers love that makes “life worth living,” as Bishop Sheen so famously put it. God: “fashioned all things that they might have being” and has formed us to be “imperishable.” That is God’s plan. Period.

Of course, there is death and destruction of being all around us. Where is God? What is His response? St. Paul gives us a clue in the second reading. He urges the Corinthians that while they excel in faith, discourse, knowledge and love, that they might also excel in “this gracious act also.” What is the gracious act? “This gracious act” must be getting close to the core of what makes all the difference in our Christian vision. Indeed it is the core. St. Paul immediately describes the “gracious act” initiated by Christ that “though he was rich, he became poor for our sakes.” The gracious act is God’s own free choice to let go, as it were, of the richness of his divinity and empty himself, becoming a slave, taking on human flesh for those of us who are threatened by sin and death.

By looking at the person of Jesus, we see the power of God going out from himself—out from his transcendence, so that he can be close to his people, close to the broken-hearted, close to the poor, the small, the weak. That’s what God does. In the person of Jesus, we see a glimpse of that same power of God, that has nothing to do with death, and everything to do with life. In today’s Gospel, while responding in the affirmative to the plea to go to heal the daughter of Jairus, Jesus shows his instinctive desire to bring life. While he is on his way to Jairus’ house, another encounter happens that reveals the same truth about the power of God’s life flowing through Jesus. It is unique among the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ encounters with the sick, the blind, and the lame.

As the woman suffering with the hemorrhages makes a desperate attempt to reach out to touch Jesus’ cloak, she has a single-hearted desire for healing to come to her from one she believes has that power. Her weakness meets Jesus’ power, and in that meeting, a transformation occurs. St. Mark describes the unusual nature of the healing: “Jesus, aware at once that power had gone out from him” looks around to find out who had received that power of life and healing. He seeks to personalize what had happened in an apparently automatic manner. “The woman, realizing what had happened to her…” then sought to approach Jesus, though she did so with “fear and trembling.” Both Jesus and the woman seek to make personal the encounter that had happened unconsciously. Upon their face-to-face meeting, Jesus confirms her not only as a person who has been healed, but as one who has been given a renewed identity: “Daughter, your faith has saved you.” Not only does Jesus overcome the chasm of isolation she experienced as one who is suffering, but he draws her into a new identity, as a beloved daughter of his Father. Not only is her “being” refashioned, as the Book of Wisdom describes it, but a new identity is given her.

This is to be the pattern of the Church, also. We are to, first, be the beneficiaries of Christ’s gracious act: he empties himself, becoming one with us so that we might become one with him in eternity. Once we have received this “gracious act” of Christ, we in turn, as members of his body, are to perform that gracious act ourselves in the world around us. A question for us today might be: how prepared am I to let go of my riches, becoming poor for the sake of those in need? How might I take part in the “gracious act” of Christ’s self-emptying love for the sake of people like us who don’t seem to deserve it?

__________

14th Sunday in Ordinary Time—July 8, 2018

Readings: Ez 2:2-5; ● 2 Cor 12:7-10 ● Mk 6:1-6

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/070818.cfm

Being opened to receiving the Word made flesh in the Eucharist

In the Jewish and Christian traditions, one of the most potent images used for understanding God’s relationship to his people is that God speaks his Word to us in a way that has organic effects. The Word of God is often likened to a seed that is planted in the soil. Jesus himself, of course, offers the “Parable of the Sower.” The sower is eager to sow the seed. He is not stingy with it. There is not a limited supply. But it depends a great deal on the nature of the soil, if that seed is going to take root. Much of salvation history, in fact, is characterized by the lack of receptivity of the people of God to listening to the Word of God. There is a lack of receptivity, a hardness of heart, in the human person. The soil in which the seed of God’s Word is planted is often too dry and rocky for anything to grow. As the Lord sends his prophets out, they are fully aware of what they are up against. In the case of Ezekiel, in today’s reading in the liturgy, the Lord warns the one whom he is asking to proclaim his Word. “Hard of face and obstinate of heart are they to whom I am sending you…But you shall say to them: Thus says the Lord God! And whether they heed or resist—for they are a rebellious house—they shall know that a prophet has been among them.” Even if the soil is rocky, and doesn’t seem like it will be receptive to the seed of the Word, the sower continues to sow.

One way or another, it is the will of the Lord to have his Word heard, to have the seed of his word take root so that it can bear fruit. But the only way this can happen, is if there is an opening in the soil, a break in the encrusted surface of the human heart, into which that seed can fall, get enveloped, and begin to grow. St. Paul points to this reality in more direct language in today’s readings. He notes, “Power is made perfect in weakness.” In the Christian vision, God looks very different, and so does the perfection of the human person. Power and fulfillment come not from what we think of as strength, as characterized by individual capacity to take care of everything on one’s own. What looks like weakness turns out to be strength, when we look at the person of Jesus. What seems like defeat on the cross, turns out to be victory. It turns out to be the fullness of the expression of God’s power. Because God’s power, at the core, is love and nothing else.

Some of this confusion shows through in today’s Gospel reading. In the course of people’s listening to Jesus, preaching with great authority, they ask a question: “Where did this man get all this?… Is he not the carpenter, the son of Mary…” This otherwise unimpressive speaker is speaking words that seem to carry great authority, great power. And precisely because of his lack of outward authority, the people are rattled. Indeed, the gospel recounts, “They took offense at him.” At the same time, the crowd is both dismissive of Jesus, and threatened by him.

As a result of the people’s own confusion and reluctance to be open to Jesus’ words, “he was not able to perform any mighty deed there.” Only those who were in need could receive what he had to give. The obstinate received nothing. Here, it seems, is the crux of the invitation for us in today’s liturgy, particularly as we come forward from this moment of hearing the Word. If we have heard with the open ears of the heart, our hearts are prepared in openness to receive the fullness of the Word made flesh in the Eucharist. God’s speech of hope becomes God’s action of love. It is only for us to recognize our need for this hope, for this love which only the Lord can give, coming forward with open hands and open hearts to say in great gratitude, “Amen.”

___________

15th Sunday in Ordinary Time—July 15, 2018

Readings: Am 7:12-15 ● Eph 1:3-14 ● Mk 6:7-13

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/071518.cfm

Preaching a word that liberates

Yesterday was Bastille Day. Over two centuries ago, this significant moment in western history is often seen as a symbol of the beginning of freedom—freedom of the common man from the coercion and domination of the absolutist monarch, as well as from the oppressive tradition and authority of the Church. This rebellion was a central moment in the history of the French Revolution. But, this marker of liberation from political oppression has also been associated with a radical secularizing impulse present in European culture ever since. In this notion of the human condition, man should ultimately be free, not only from the State and the Church, but even from the authority of God, in order to be truly free.

However, we also know that certain kinds of freedom very quickly lead a person directly back into slavery when this freedom is exercised in isolation, for the sake of self-interest alone. Since the French Revolution, a crucial mistake has been made in western thought that confuses these varying manifestations of freedom. We are reminded, in today’s liturgy, of the distinction between these notions of freedom, especially in light of our ultimate freedom experienced only from within the identity of the children of God.

We are given a model of what this freedom entails in the first reading today. The prophet, Amos, experiences his call from the Lord, which is not easy to respond to but which he does with great courage. Threatened by his message of repentance and justice for the most vulnerable in their society, the king bans Amos from preaching in Bethel, the place of the king’s sanctuary. Amos responds in humility that highlights the paradox of what true authority and true freedom look like. He demurs, “But I am just a shepherd and dresser of sycamores.” In all simplicity and humility, he admits his station in society. Yet, precisely in this humility, the greatness of God’s authority can shine through most perfectly. These are not his own ideas, nor his own power, that he asserts, but rather nothing more, and nothing less, than the sovereignty and truth of God alone.

In the reading from the Letter to the Ephesians, we are confronted with the reality that we have been chosen “before the foundation of the world, to be adopted children” of God the Father. As such, we are in a position to receive a divine inheritance. Of course, we receive this inheritance through no merit of our own. It is freely given because of the family into which we are born. We do not have the authority to select our families. They are given to us, as we are given to them. The same is true of our ultimate, spiritual family that is given life, and formed, by our heavenly Father. These familial relationships are given, and the truth of who we are comes, not when we determine our own fates, but when we freely, humbly, and gratefully abide from within these relationships. From within these sets of relations, we find the truth of our identities and ultimately, our true freedom.

Providing a kind of orientation for us in this true identity of ours, Jesus reveals his ultimate Lordship, over both physical and spiritual reality, to his apostles in today’s Gospel. In sending the twelve in pairs to cast out unclean spirits, he gives them a share in that authority and mission, given him by the Father, in order to exercise his Lordship over creation and human history. Curiously, the apostles are sent on this mission, being both poor and without the possibility of being self-reliant. They are assured that what they might accomplish is done so, not by any merit of their own, but only by the grace of God working through them. In their obedience to this call—extended to them in order to share in the mission of the Son who freely obeys the Father—we are given models of what it looks like to live in true freedom, rather than some truncated version that modern secular culture insists upon.

_____________

16th Sunday in Ordinary Time—July 22, 2018

Readings: Jer 23:1-6 ● Eph 2:13-18 ● Mk 6:30-34

http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/072218.cfm

The lost brought home.

The prophet Jeremiah speaks a word of woe in today’s reading. He reprimands those shepherds who lead their flocks astray, away from the pastures where real nourishment is to be had. He laments the consequence of this misleading, namely, that there are now those who find themselves far away from God, and from the fullness of life. But, the Lord speaks through Jeremiah, saying that there is no need to despair, for “I myself will gather the remnant of my flock.” Where shepherds have failed in their responsibilities, the Lord himself will step in, providing the care needed for the sheep. This is what is in the Lord’s heart. Though he chooses to rely on people like us to offer pastoral care to his people, he continues the work himself when we fail. He finds new ways to feed his flock. He is relentless in his care for his people.

The liturgy of the Word this week focuses on this reality of humanity’s separation from God, and the nature of God’s response to “gather the remnant” back to him. In the second reading, from the Letter to the Ephesians (and to us today), we hear how we “who once were far off, have become near by the blood of Christ.” Ultimately, this is the act of God, wherein He fulfills what he said to Jeremiah: “I myself will gather the remnant of my flock.” St. Paul’s letter goes on to describe how it is the cross of Jesus Christ that “puts enmity to death.” Death, of course, is that ultimate distancing and separation which causes suffering in our human condition. How is it that our separation from God is a separation that can be traversed only by the cross? How are we brought back to God precisely by the “death of God,” in Jesus Christ? We are brought back by the blood of Christ. That is to say, it is only by the ultimate and perfect act of love by God, who is love itself that, in Christ, God gives away everything he’s got—his whole self, his whole heart that is pierced—in order to draw us back to himself. It is from this heart, this source of love from which this blood and life flow, overcoming the chasm of death that would otherwise separate us from God.

In the Gospel for today, we get a glimpse of Jesus’ own understanding of this mystery, and his intentionality about bringing about this reunion of humanity with God. As he had gone away to rest, to be with his Father, the people who are in need follow him to the place of his seclusion. As he disembarks from the boat, we hear, “his heart was moved with pity for them for they were like sheep without a shepherd.” Jesus, the Good Shepherd—who is so different from those false shepherds that Jeremiah warned about in the first reading—sees in the people before him, those who are “far off.” It is his desire to bring them back “near” to his Father. In proceeding to perform the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves, he provides, as it turns out, a foreshadowing of what he will offer at the Last Supper, wherein he will give, as a free gift, his own body and blood for the disciples to be nourished. This Eucharistic gift, that is hinted at in the multiplication of the loaves, and that will be offered on Holy Thursday, will be itself an anticipation of the sacrifice he will make the next day on the cross on Calvary. In his gift of himself on the Cross, the blood he will pour out will become the means of our own reconciliation, our own coming back near to the Father. It is precisely in this Eucharistic mystery that we are being drawn right into the middle of this season of ordinary time. We begin to see what God promised so many centuries earlier in his word to Jeremiah, promising that he himself will “gather the remnant of my flock.”

_____________

17th Sunday in Ordinary Time—July 29, 2018

Readings: 2 Kgs 4:42-44 ● Eph 4:1-6 ● Jn 6:1-15

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/072918.cfm

Hunger satisfied

The culmination of every celebration of the Eucharist is the receptive act of being fed by God. We come to the Mass not primarily to gain insights about life, though these might be given along the way. The source and summit of our lives as Christians are not merely a cerebral, or even purely spiritual activity, but a bodily one, as well. We are not primarily looking for new knowledge. We seek a satisfaction of our hunger. It is this hunger that the words of Scripture ask us to reflect upon today.

In the first reading from the Second Book of Kings, we encounter the great prophet, Elisha, who is living in the midst of great trial. He is witnessing the breakdown Israel due, in large part, to the infidelity of their leaders. Notably, the more the kings are unfaithful, the more the people end up suffering. There is a series of stories contained in this section about the poor being on the brink of starvation. However, through the prophet Elisha, they are reminded, again and again, that trust in their God is all that is required, no matter how bleak things start to look. It is a time of desolation for the people of Israel, especially the poor, and this desolation is represented concretely in the experience of the great prophet being on the brink of starvation. In the midst of this, a man comes to Elisha setting before him a few loaves of bread. Elisha responds saying he ought to give it to the crowds who are hungry, for: “They shall eat and there shall be some left over.” Though it seemed like it wouldn’t be enough, when the loaves were given, the people, of course, had been fed and, indeed, “there was some left over, as the Lord had said.”

The Gospel account of the feeding of the five thousand represents a kind of fulfillment of what is prefigured in the Elisha story. It is itself a pre-figuration of the Eucharist that he would establish at the Last Supper, in which we still participate on a daily basis in the Church in every corner of the world today. Indicating that the Passover is near, we are given a hint that the re-signifying of the Passover, that Jesus will initiate the night before his Passion, is beginning to unfold, is being anticipated, even now. Taking up the five loaves and two fish, which come from the people assembled there, he immediately gives thanks to his Father, just as the priest does every day at the beginning of the liturgy of the Eucharist. The abundance of the Father’s goodness is revealed in the fragments left over after the five thousand had eaten.

In case we are not getting the picture through these concrete stories of the hungry being fed, we are given a blunt theological truth right in the midst of the liturgy of the Word. The psalm today reiterates this truth, as the whole congregation proclaims: “The hand of the Lord feeds us; he answers all our needs.” That sounds like a nice sentiment, but it points to a more difficult truth. It is the hand of the Lord, not our own hand, that is able to feed. We are unable to feed ourselves on our own. This is the truth of our existence. It is what it means to be a child of God, which is the “call we have received” that Paul refers to in the epistle. In order that we might deepen that sensibility of the ultimate truth of our existence, it is necessary that, on a day-to-day basis, we practice living out of this truth in our ordinary relationships. He urges that we “bear with one another” with great humility, gentleness, and patience. Being fed by the Lord has consequences on a social plane, as well. We must bear with one another because we are in this together. God desires to save us together. We do not have the liberty to cast aside those who are inconvenient or even annoying. This is part of our poverty that we realize in ordinary, daily living. We are always poor. We are always hungry. It is only the Lord who can, and will, feed us, together.

I was hoping Father Collins would have had a homily on Humanae Vitae the Sunday of July 22 with the 50th anniversary coming up that week.

No, because the homily is supposed to be on the particular Scripture passage/s for the day.

https://www.ncronline.org/blogs/ncr-today/pope-francis-says-no-boring-homilies

Yes! Humane Vitae is THE prophetic encyclical of the past 100 years!

it is very nourishing, keep on with that spirit that God has given you father