Introduction

In John 1:38, Andrew and another disciple pose the following question to Jesus: “Rabbi, where do you live [Gk. méno]?” What do they mean? Certainly, on one level, they want to indicate their desire to come under the tutelage of the master in the manner of a first-century disciple. However, a close reading of John’s entire Gospel account reveals that there is more. Seen in the context of the Gospel as a whole, the question of the two disciples in John 1:38 has a deeper, eschatological meaning which frames Jesus’s entire discipleship formation program, which is presented in the Fourth Gospel as a key to Trinitarian intimacy found in faithful Christian discipleship. With an emerging ecclesial focus on discipleship formation, an examination of Jesus’s interaction with his closest disciples such as this becomes particularly pertinent and practical for evangelization not merely in the first century, but also in the twenty-first century.

The Prologue

The prologue of John’s Gospel account provides a window into the underlying theology of the narrative by pulling back the veil which separates the heavenly and the earthly. Rudolph Schnackenburg writes that John’s prologue “has rather the character of a theological ‘opening narrative’, the believer’s telling of the ‘pre-history’ which becomes the ‘history of Jesus’ at the historical turning-point of the incarnation.”1 The telling of happenings “in the beginning” sheds light upon the actions of the Word made Flesh in time. In the prologue, the Evangelist casts the overarching theological vision of the coming narrative. Therefore, should the hearer desire insight into the “theme” of the Gospel narrative, he might look to the prologue as a rudder to guide his interpretation.

As such, the final verse of the prologue casts light on the entire evangelical mission of the Son. “No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father [Gk. eis tòn kólpon toỹ patròs], he has made him known.” (John 1:18, RSV-2CE) Schnackenburg thus interprets:

The prologue concludes with a pointed statement of the one historical (aorist) revelation brought by the unique Son of God. Here we can recognize once more the Christological interest which made the evangelist put the prologue before the Gospel narrative proper: only the demonstration of the divine origin of the revealer can throw proper light on his unique significance for salvation, as it is later displayed in the words and works of the earthly Jesus.2

It is the divine origin of Jesus which illuminates his earthly words and works. The only one who can make God known is the only-begotten God who lives in the bosom of the Father. The importance of Jesus’s divine origin with reference to the formation of his disciples will come to bear below as we examine John 14.

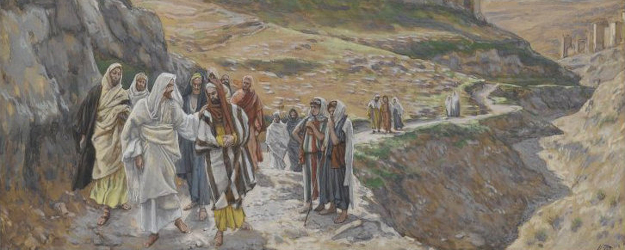

The Disciples’ First Encounter with Jesus

Andrew and the one only identified here as “the other disciple” are first disciples of John the Baptist. However, after twice hearing their teacher proclaim Jesus of Nazareth as “the Lamb of God” (John 1:29, 36), they do the only logical thing. They follow him. John had said that he was preparing the way for another and this Jesus is clearly that other. Therefore, as good disciples of John, Andrew and the other disciple follow after Jesus. Maybe they are being deferential, or maybe they are simply too nervous to speak. Whatever the case, Jesus speaks first, “What do you seek?” (John 1:38)3 The disciples respond in a way both simple and profound. “Rabbi (which means Teacher),4 where do you live [ménō]?” (John 1:38) Where are you staying? Where do you remain? All three are possible translations among many for the Greek verb ménō.

As one can see from the original Greek, there is a clear theme of remaining [ménō] in this last part of John’s first chapter. The Spirit remains [ménō] upon Jesus (1:32); Jesus remains [ménō] at some place (1:38); and the two disciples remain [ménō] with him (1:39). Perhaps the two disciples want to know something of what that means. Perhaps they want the spirit to remain upon them. Certainly, they want to follow Jesus, to go to his home, to learn from him. And they do; they “come and see” the place where Jesus is staying [ménō] (1:38) and remain [ménō] with him that day (1:39).

What, then, were the disciples seeking in asking the question, “Rabbi, where are you staying?” (1:38) Were they merely asking for Jesus’s “address” or were they searching for something more? Certainly, Andrew and the other disciple were asking for the physical location of Jesus’s dwelling. As John’s narrative unfolds, it becomes clear that they wanted to be near Jesus, to be in his physical presence. They wanted to follow him and to learn from him. But, even from this very first encounter with Jesus, the evangelist is revealing something more — something deeper — about true Christian discipleship. True disciples want to know where Jesus remains because they want to be with him and remain there themselves.

Raymond Brown comments thus on the existential character of the disciples’ question:

Notice that in the beginning of the process of discipleship it is Jesus who takes the initiative by turning and speaking. As John 15:16 will enunciate, “It is not you who chose me. No, I chose you.” Jesus’s first words in the Fourth Gospel are a question that he addresses to every one who would follow him, “What are you looking for?” By this John implies more than a banal request about their reason for walking after him. This question touches on the basic need of man that causes him to turn to God, and the answer of the disciples must be interpreted on the same theological level. Man wishes to stay (menein: “dwell, abide”) with God; he is constantly seeking to escape temporality, change, and death, seeking to find something that is lasting. Jesus answers with the all-embracing challenge to faith: “Come and see.”5

Rabbi, where do you remain? My Jesus, I have become fascinated by your beauty. I have been intoxicated by the sweet aroma of holiness (cf. Song of Songs 4:16). I long for that which is beyond this valley of tears. I have repented of my sins in the waters of John’s Baptism, but now I desire more. I desire to remain in the Fire of Love, the Fire of Baptism in the Holy Spirit (1:32–34). My Jesus, where to you abide?

There is something more for the disciples, but what more? They cannot yet understand that where Jesus truly abides is “in the bosom of the Father [Gk. eis tòn kólpon toỹ patròs]” (1:18). To learn truly where Jesus lives, they must “come and see” (1:39).

The Last Supper Discourse

The disciples do come and they do see. For what is commonly reckoned as three years, they remain with Jesus — they physically live with him and learn from him. Yet they will only truly learn where he remains in their last conversation with him before his Passion. In some sense, then, the question of where Jesus remains/lives/abides contextualizes Jesus’s entire discipleship formation program.

Brown has wisely pointed us to John 15 as a hermeneutical key to the interpretation of John 1:38.6 Here in the Last Supper Discourse we immediately realize that the concept of “remaining” or “abiding” is at the forefront of both Jesus’s first and last conversation with his disciples during his public ministry. In other words, the concept of ménō frames Jesus’s formation of his disciples.

Let us then turn to this last conversation. As the drama unfolds around the identity of the traitor, the beloved disciple rests his head in a place now familiar to us from the prologue (1:18). “One of his disciples, whom Jesus loved, was lying in the bosom of Jesus [Gk. en tō kólpō toũ Iēsoũ].” Jesus, the only-begotten Son, is “in the bosom of the Father” (1:18) and the beloved disciple, a Johannine model of Christian discipleship, is “in the bosom of Jesus.” (13:23)7 The only-begotten Son makes the Father known, and the beloved disciple makes his master known. “These [things] are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:31)

As the beloved disciple rests in the bosom of Jesus, a question arises from Andrew’s brother, Simon Peter. “Lord, where are you going?” (John 13:36) Here, in the last conversation with his disciples before his passion — as the end of their formation in discipleship approaches — we are taken back to the beginning. “Master, where are you staying [ménō]?” (1:38)

Here, as public ministry moves to passion, Jesus finally verbalizes the answer, an answer heretofore given only bit by bit through his words and his actions:

In my Father’s house are many rooms [monaì]; if it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you? And when I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, that where I am you may be also. (John 14:2-3)

Jesus lives in his Father’s house and prepares a “remaining place” [monaì] for his disciples who believe in him. They have come; they have seen; and they will “remain”. μονή [monē] is the noun corresponding to the common and important Johannine verb μένειν [remain; ménein], and hence it will mean a permanent, not temporary, abiding-place (or, perhaps, mode of abiding).8 This “remaining place” is an eschatological reality, expressing the entire goal of the disciple of Jesus: to acquire an eternal “remaining place” in the house of the Father. It is in this eternal monē that the disciple’s true desire is answered. This is Jesus’s goal as he forms his disciples, foreshadowed in John’s prologue and begun in the very first conversation between Jesus and his new disciples. Now, approaching the climax of the narrative, the true disciple who remains in Jesus’s words can remain with the Son and the Father and the Spirit forever.9 “The slave does not remain [ménō] in the house forever; the son remains [ménō] forever.” (8:35)

In 1:38, Andrew and the other disciple first ask where Jesus remains. In 2:12, the disciples together remain with Jesus in the earthy city of Capernaum. Supplemented by the aforementioned words of Jesus in 8:35, Jesus — in 14:1–3 — shows that this earthly remaining is completed and fulfilled in the disciples’ eternal remaining with himself and with the Father. This eternal remaining is the goal of Christian discipleship. This is the reason that, while always remaining in the bosom of the Father, “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:18, 14)

Conclusion

The brief study expounded above shows that, at least in the intention of the evangelist, the question of Andrew and the other disciple in John 1:38 is more than simply a request for Jesus’s “address.” Rather, it is a cry of the heart of the true disciple who longs to abide with the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But the path to a heavenly habitation is not a short one. To learn the way, one must “come and see.” (1:38) To learn the way, one must dwell with he who is the way and the truth and the life. (John 14:6)

Significantly, this means the theme of remaining with Jesus is an essential characteristic of a disciple’s formation and not simply part of the Scripture’s spiritual sense. Rather, the literary composition of the Fourth Gospel indicates that such a theme is woven into the structure of the text itself and thus part of the literal sense intended by the evangelist.10 This deep, spiritual meaning is not one imposed by popular piety of later ages; such eisegesis would be inauthentic. Rather, the deep need for the disciple to abide with Jesus, to live with Jesus, and to draw life from communion with Jesus comes to the twenty-first century Christian from the heart of the evangelist and the depths of the Spirit who inspired him.

Might we then, like the first disciples, come and see the place where he eternally remains, and choose by his grace to dwell with the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit into eternity (1:39; 14, 1–3).

- Rudolph Schnackenburg, The Gospel According to St. John, vol.1, trans. Kevin Smyth (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968), 1:224. ↩

- Schnackenburg, John, 1:224; emphasis added. ↩

- He speaks in words similar to those which he will later speak to Mary Magdalene at the tomb. As Robert H. Smith writes, “It is almost as though this question brackets the entire Gospel.” Smith, Robert H., “‘Seeking Jesus’ in the Gospel of John,” Currents in Theology and Mission 15:1 (1988), 52. ↩

- The Hebrew word rabbi literally means “my great one” but, as evidenced by the Gospel accounts themselves, had by the mid–first century AD already acquired the idiomatic meaning of “teacher.” ↩

- Raymond Brown, The Gospel According to John I-XII, Anchor Bible, vol. 29 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 78–9. Emphasis added. ↩

- See above. Brown, John I-XII, 78–9. ↩

- Regarding the beloved disciple’s place as the ideal disciple, see the following texts: C.K. Barrett, The Gospel According to St. John, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1978), 588; Rudolph Schnackenburg, The Gospel According to St. John, vol.1, trans. Kevin Smyth (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968), 378; Melvyn R. Hilmer, “They Believed in Him: Discipleship in the Johannine Tradition,” in Patterns of Discipleship in the New Testament, ed. Richard N. Longenecker (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), 89; and Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary, vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2003), 656, 1144. ↩

- Barrett, John, 456–7. ↩

- As regards the Spirit, see again John 1:32 and 14:16–17. ↩

- For a discussion of the senses of Scripture, see Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, (London: Burns, Oats, & Washbourne, 1921), I.1.10. Verbum. ↩

Thank you for this reflection on “meno”. It was quite helpful to my prayer.