The Solemnity of Corpus Christi proclaims the truth that the Incarnate Son of God, having ascended to His Father’s right hand in heaven, remains present and active in His Church “until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

The truth of Christ’s substantial presence in the Holy Eucharist involves two closely related, though not identical, doctrines, those of transubstantiation and of the Real Presence. Survey data tells the sad story that even many Catholics today do not believe in or understand these doctrines.

In his sermons for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, given over the course of three decades at Corpus Christi Church, London, and in his other writings on the Eucharist, Ronald Knox (1888–1957) sheds a great deal of light on these truths concerning the what St. Thomas Aquinas and the Catechism of the Catholic Church call the “Sacrament of sacraments.” Knox’s teaching is that of the Church’s Tradition, especially as expressed magisterially by the Council of Trent and theologically by St. Thomas.

Knox, one of the great preachers and apologists of the English Catholic world during the first half of the twentieth century, wrote very often on the Real Presence and transubstantiation. Knox explains the Eucharistic mystery with coherence, lucidity, warmth, and persuasion. The astounding truth of the Real Presence is always prominent in Knox’s sermons and other writings on the Eucharist. He never ceases to marvel at Christ’s condescension in coming to his people under the appearances of bread and wine. The startling and awe-inspiring fact of Christ’s presence constantly presses itself upon Knox’s imagination, and he tries in corresponding measure to share the wonders of Christ’s Eucharistic presence with his readers and hearers.

Christ’s Real Presence in the Eucharist

Knox accepts the doctrine of the Real Presence as part of the Church’s unbroken Tradition, guaranteed by the words of Christ himself.1 A starting point in thinking about Knox’s understanding of the Real Presence is its distinction from the other ways in which God is present in the world. Of course, God is present everywhere, at all times.2 Having created us as sensory creatures, however, God gives himself to us in a way that appeals even to our senses. “Because he knows how much we all depend on our ordinary ways of thinking, he has not been content with all the ordinary gifts which he bestows on us.” No, he has left us the Eucharist, in which Christ is present in a manner different from that in which he is present everywhere. The Eucharist allows us to say concretely and directly, “Here is God” and even, “This is God.”3

For Knox, the whole sacramental life of the Church is a continuation of the Incarnate Christ’s presence and activity in the world. The Eucharist is an even more startling act of condescension on God’s part than the Incarnation.4 In the Eucharist the whole Christ is substantially present: “In the sacred Host, in each sacred Host, the whole Body of Christ is present, his Body, his Blood, his Soul, his Divinity.”5 And this is so in all of the places where the Blessed Sacrament is throughout the world. “Christ is present; is present in space, though not under the conditions of space.”6 In his incarnate life, Christ assumed a full human nature, including the limitations of time and space.7

After his Ascension, Christ chooses to become present sacramentally in such a way that allows both for his full, substantial presence and for that presence to occur down through the ages and all over the world. Of all of the miracles Christ performed in his earthly life, the institution of the Eucharist was his greatest.8 It also was and remains an act of unfathomable mercy on Christ’s part: “We are not worthy of the least of his mercies, and he gives us — himself!”9 Knox continues in the same sermon, “And, above all, the grace of the Holy Eucharist, no transient influence of the divine mercy but God himself, is lavished upon us with reckless bounty; we have but to stoop to gather it, and it is ours!”10 In the Eucharist, Christ gives to his faithful not what is their due, since it is impossible for them to earn so great a gift, but rather he gives himself out of the greatness of his love and munificence. Christ allows for easy access to himself in the Eucharist, knowing the risks brought by familiarity and accepting them for the sake of giving himself to his people:

God forgive us, we despise his graces because he has made them so cheap for us; the heavenly bread which is offered us without money and without price we put down, for that reason, as not worth having! That is not the law of the divine economy. All the graces bestowed on our blessed Lady and the saints, all the visions and ecstasies and the power of working miracles, are not to be compared in value with what he gives us in holy communion; for that is himself. This gift, which is himself, is not for the few, but for everybody. O res mirabilis, manducat Dominum pauper, servus et humilis: we are all paupers in his sight, all slaves, all creatures of earth, and he will make no distinction between us. He only asks that we should purge our consciences of mortal sin, and so come to him, asking him to bring just what he wants to give us, just what he knows that we need. “I am he who bade this be done; I will supply what is lacking to thee; come, and receive me.”11

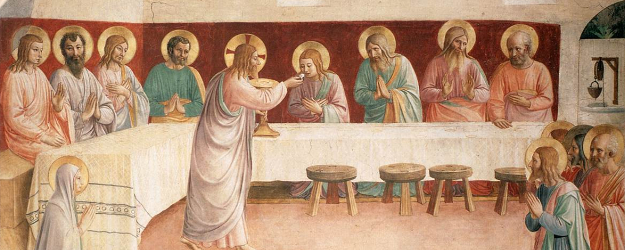

Knox emphasizes that the Eucharist is a gift given by Christ to his people, “a gift surpassing all the riches of the world, himself.”12 This truth is clear from the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. In one sermon, Knox asks his hearers to contemplate the image of Christ holding the Sacred Host and chalice at the Last Supper, depicted in so many works of art. This image offers an intimate look at the relationship between the Incarnation and Christ’s sacramental presence:

Think, for a moment, of the paradox which that involves — the figure of our Lord at the last supper. You see before you what seems to be the form of a man; that man is Jesus Christ, his body, his blood, his manhood, his divinity. You also see before you what seems to represent a round disc of bread. That which looks like bread is also Jesus Christ, his body, his blood, his manhood, his divinity. Jesus Christ, then, holds himself in his hands. Host and banquet, priest and victim, are one.13

Another image Knox uses is that of a looking-glass. When a person looks into a looking-glass and sees his or her reflection, the appearance is exactly that of the person looking, but without any corresponding substance. In the Holy Eucharist, the substance of Christ’s Body and Blood is present, but without the corresponding appearances.14 Knox again considers the moment when Christ held the Sacred Host at the Last Supper:

His eyes were fixed on something that didn’t look like himself but was himself. It looked like an ordinary piece of bread; but the reality wasn’t just a piece of bread. The reality was something more real than that. It was himself, who is reality. What looked like a piece of bread was, you see, a kind of supernatural mirror — not reflecting, as other mirrors do, the appearance without the reality; it reflected the reality without the appearance.15

Knox compares, rather than contrasts, the Eucharist with a looking-glass insofar as each can be broken with the effect of multiplying the reality involved. A person looking into multiple broken pieces of a mirror sees his or her reflection in each one, rather than seeing his or her once integral reflection now divided amongst the pieces. So too, with the Eucharist, when the Host is broken each part contains the whole Christ, not some part of him: “The reality has reproduced itself in each broken fragment, the whole reality, and it remains real as ever.”16

The Real Presence is the fully concentrated presence of the Lord, who in return summons our fully concentrated attention. Knox compares the Eucharistic presence of Christ with the heat of the sun: “As the rays of the sun, whose heat is present everywhere, are caught and focused in a single point by the lens of a burning-glass, so our Lord will have these celestial visitations of his focused for us, crystallized and concentrated for us under the forms of outward things, when he comes to us through his sacred humanity in the Holy Eucharist.”17

As with any such images, this one has its limitations, but Knox is making an attempt to describe a great mystery with as much truth, clarity, and vividness as possible. And he is careful to use such images with integrity, at times alluding both to the similarities and differences of the two realities he considers and not overstating their similarities for the sake of the preacher’s convenience. In this case, for example, the analogy “limps” at the point when one considers that not literally all of the sun’s heat is concentrated through such a lens, whereas the whole Christ is indeed present in the Eucharist. Yet Knox’s point here is to help people understand that while Christ in his divinity is present everywhere, he is nevertheless fully present in a distinct and special way in the Holy Eucharist. And this Real Presence by its very nature calls for the central place in the lives, minds, and hearts of men. “In a world of shifting values, there is one fixed point on which our hearts can rest, one fixed star by which our intellects can be guided,” Knox writes. “It is the personal presence of our Lord on earth, yesterday, today, and as long as the earth endures.”18

Knox on Transubstantiation

As we move from Knox’s treatment of the Real Presence to that of transubstantiation, mention should be made of a text to which Philip Caraman drew attention in an editor’s note included near the front of the volume Pastoral and Occasional Sermons. Caraman quotes a statement by Knox in his sermon, “The Divine Sacrifice,” in which Knox writes, “the outward forms of bread and wine inhere in, are held together by, an underlying reality which is the very substance of his own body and blood.”19 Caraman opines that this text “should be understood in a loose sense, and not with the precision which a theologian would give to the words. In the Eucharist, the appearances of bread and wine remain present, of course, but without a substance in which they inhere.” Caraman writes that this text was pointed out to him by someone else.

There is, in fact, another text in the same volume to which Caraman does not allude but which makes the same point. In his sermon “One Body,” Knox writes, “For here, beyond the furthest reach of our earth-bound imaginations, the accidents of bread and wine inhere in a substance not their own, the very substance of our Lord’s body and blood.”20 Both St. Thomas Aquinas and the Catechism of the Council of Trent teach that after transubstantiation the accidents of bread and wine depend upon the power of God and do not inhere in a substance, since the substances of bread and wine do not remain and it is impossible for the appearances of bread and wine to inhere in the substance of Christ’s Body and Blood.21 Caraman writes that Knox, “were he alive, would doubtless wish to clarify” his meaning about the relationship between substance and accidents in the Holy Eucharist. The context of Knox’s whole teaching on transubstantiation and the Real Presence, as well as his unfailing deference to the Magisterium and the orthodox theological tradition, give good grounds for Caraman’s defense. It seems doubtful that Knox radically misunderstood the metaphysical question involved. Perhaps this was an imperfect attempt on his part to offer more than a merely a negative description of the relationship between the Eucharistic substance and accidents. Perhaps it was an attempt to explain in some positive terms what it means to say that the Body and Blood of Christ are present under the appearances of bread and wine, in a way his hearers and readers could understand.

This difficulty aside, Knox speaks often of transubstantiation in his sermons in ways that would have been illuminating and edifying to his hearers. Knox’s consideration of two of Christ’s miracles provides a good example of his ingenuity in explaining transubstantiation. How the Real Presence comes to be is “a miracle and a mystery”.22 Knox asks two questions in this context: first, “Can God really turn a thing into something else altogether?”; and secondly, “Can God multiply his own Body’s presence, so that it is equally present in all the million Hosts of the world?”23 Knox immediately answers that God can do these things, invoking two well-known miracles Christ performed during his public ministry: the miracle at the wedding feast at Cana (Jn 2:1–11) and Christ’s multiplication of loaves (Jn 6:1–14). These miracles demonstrate, respectively, Christ’s power to change one substance into another and to multiply something’s quantity.

In the miracle at Cana, “Our Lord changed water into wine; he didn’t annihilate water, and then create wine.”24 Knox also refutes the idea that only an accidental change took place, and that what Christ produced remained substantially water, with only the accidents of wine.25 Scripture testifies that what the wedding guests drank was, indeed, true wine. The miracle involved a “total change” of both substance and accidents, from those of water to those of wine. Positing anything less would call into question the authority of Scripture and suggest a form of deceit, since the reality would be something less than what is suggested by the accidents.26 In the case of transubstantiation, Christ brings about a change of substance, this time without changing the accidents. Why is this not a deception? Because “a deception is something that is less real that it looks; but the holy Eucharist is just the opposite; it is something actually more real than it looks.”27

The miracle of the multiplication of the loaves is the “exact correlative” of the miracle at Cana, Knox suggests, since at Cana Christ changed everything except the quantity of liquid when he changed water into wine, whereas in the feeding of the five thousand he changed nothing except the quantity of the bread and fishes. “In one case there is change without multiplication; in the other multiplication without change.”28 It is by this power of multiplication that an otherwise quantitatively limited reality (the Body and Blood of Christ) can become present under the appearances of bread and wine in countless times and places where transubstantiation takes place. Together, these miracles possess “a kind of sacramental significance.” They have the “special purpose” of confirming Eucharistic faith.29 Knox frequently calls transubstantiation a miracle, and so it stands to reason that certain miracles Christ performed in his public ministry should point to this greatest of his miracles.30

As we have seen, Knox refers to transubstantiation both as a miracle and as a mystery. God’s wondrous work in the Eucharist transcends the human capacity for thought: “He has broken into the very heart of nature, and has separated from one another in reality two elements which we find it difficult to separate even in thought, the inner substance of things from those outward manifestations of it which make it known to our senses.”31 And yet faith and reason may work together to appreciate and understand this great mystery ever more deeply. Knox even preached an entire sermon on transubstantiation at a time when the concept was highly controverted in England and Catholics needed to understand their faith in order to defend it.32

Transubstantiation effects a total change of the substance of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ.33 God in his limitless creative and miraculous power “can create and can annihilate, can also change this into that.” He has chosen to employ these powers in the Eucharistic change in a unique way: “In the Blessed Sacrament it is his will that the change should be supra-sensible, and that the substance which is truly present should be only seen, only tasted, by faith.”34

At one point Knox takes up what he calls the “blasphemous suggestion” of a contemporary Anglican bishop, who had proposed that a consecrated Host be subjected to a chemical analysis to test its reactions compared to those of an unconsecrated host. Not only does Knox find curious the bishop’s faith in science’s ability to penetrate to the “innermost secrets of physical reality,” but he also clarifies that the idea that such analysis could disprove transubstantiation is impossible. “However far Science may progress . . . it is not possible that it should ever arrive at the point of separating accidents from their substance, since the distinction here, albeit real, is a metaphysical and not a physical distinction,” Knox writes. “Whatever tests Science proposes must necessarily report, in the long run, to our senses; such are their terms of reference. Whereas the change that takes place in transubstantiation is, as I have said, suprasensible, and cannot submit to the award of any physical test whatever.”35

In his sermon “Peace in Ourselves,” Knox addresses the relationship of substance and accidents after transubstantiation in a way that helps balance off his less clear references to inherence, which we have seen above. Reflecting upon the Holy Eucharist as a sacrament of unity, Knox notes that it is typically substance that acts as the “single principle of unity” for the various accidents of that substance. Substance is “the linch-pin which holds them all in place.” Remove the linchpin of substance, and one would normally expect the dissolution of the accidents. In transubstantiation, something unique and wonderful happens: “Take away the substance, and, by a miracle, so stupendous that our minds can hardly conceive it, the accidents do not fall apart; they remain there to be the garment and the vehicle of a quite different and a far greater substance, that of our Lord’s own body and blood.”36

Only the power of God can do this. In a passage that speaks to the divine power at work in transubstantiation and draws out an important implication with regard to the unity of the Church, Knox writes of the persisting unity of the Eucharistic accidents:

His word upholds them; the same word which prayed, at the last supper, that the apostles might remain one; might remain one even when their Master, the focus of loyalty by which their fellowship maintained itself, was taken away. The unity which unites three persons in one Godhead, the unity which preserves in being a set of accidents which have lost their substance — that is the unity we Christians pray for, and claim as our own when we gather round our Father’s table at the Holy Eucharist.37

Conclusion: Mysterium Fidei

Faith alone allows access to this sublime mystery, in which Christ becomes fully and substantially present under the appearances of bread and wine. He does so, even at the risk of exposing himself to the scorn of the faithless.38 Many more texts could be produced demonstrating Knox’s affirmation of the truth of transubstantiation and the Real Presence. It suffices to summarize, however, by saying that Knox taught that the words of consecration bring about a total change of the substances of bread and wine into the substances of the Body and Blood of Christ, and that in the Holy Eucharist Christ remains present in a unique and utterly complete way, Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity.

To perceive these truths requires faith, and Knox himself was a man of strong Catholic faith, from before the time of his reception into the Catholic Church in 1917. Again and again, Knox expresses his amazement at God’s love and generosity towards his people in giving them such a great Gift. At a time when Modernism was exercising a deeply corrosive power in biblical studies and theology, Knox offered the Church’s traditional teaching with great clarity, learning, eloquence, and the persuasive force of a seasoned apologist. His writings on the Eucharist and a host of other topics deserve the attention of today’s Catholics, facing as they do the relentless attempts of society to marginalize the Faith and to bring about the eclipse of God. This generation needs new defenders of the truth that the Son of God remains with his people, giving them strength, drawing them to himself, and inspiring their witness to a world that often fails to welcome him simply because it does not know he is here, knocking at the door of each human heart.

- Ronald Knox and Arnold Lunn, Difficulties: A Correspondence About the Catholic Religion Between Monsignor Ronald Knox and Arnold Lunn (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1952), 232. ↩

- “God . . . is close to us all the time. We may think of him if we will as present (although without any limitation of space) in the whole world of nature around us; we may think of him as present in the air we breathe, in the sky above our heads, or in the earth under our feet, and we shall not be deceiving ourselves, we shall only be recognizing something which is true. Or again, perhaps with more profit, we shall think of him as directly present to our own immaterial souls, as communicating to them the life by which they live and every movement which stirs them; the motions of the divine grace are, in literal fact, as near to your soul as the wind which fans your cheek is near to your cheek.” Ronald Knox, “Holy Communion,” Retreat for Beginners (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1960), 133–34. ↩

- “Holy Communion,” 134. “One thing we can say, without bewilderment or ambiguity — God is here.” Ronald Knox, Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, “Where God Lives,” (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2002), 260. ↩

- “And if, in his Incarnation, God stooped towards us and condescended to our level by uniting his Divine Nature with a human nature, which, though created, was created in his image, was part of his spiritual creation, how much lower he stoops, how much more he condescends, when he hides himself in the Holy Eucharist, veiled under the forms of immaterial, insensible things!” Ronald Knox, “Holy Hour—A Hidden God,” A Retreat for Lay People (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011), 95. ↩

- “Holy Communion,” 135. ↩

- “The City of Peace,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 250. ↩

- “Where God Lives,” 260. In his sermon “Prope Est Verbum,” Knox writes, “If (Christ) was to live the life of an ordinary man, he must be like all other natural objects present only in one place, absent from all other points in space; his immediate presence must be confined and his immediate attention must be concentrated on a particular set of people . . . that life must come to an end; his presence on earth would be limited to a particular period of history. . . . We, living nineteen centuries after the time of the emperor Tiberius, living far away at the end of the next Continent, should never be able to cry ‘Jesus of Nazareth passes by’ in our turn. The merciful effects of the Incarnation might be applied to the needs of our souls, but we should never be able to feel, in this life, that the Son of God had come close to us too, so far away, so many centuries later. To kindle our love with any consciousness of his near presence, the Incarnation was not enough. To secure that further object, the Incarnation of our Lord was at once perpetuated and universalized in the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. Wherever there was a priest to celebrate the holy mysteries, there should be Bethlehem, and there Calvary.” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 355–56. ↩

- “Giving of Thanks,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 264. Here Knox adds a detail that pertains to the role of gratitude in worship, considered above. He notes that in all of the New Testament accounts of the institution of the Eucharist (Matthew, Mark, Luke, 1 Corinthians), it is said that Jesus gave thanks as he consecrated the bread and wine into his Body and Blood. ↩

- “The Gleaner,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 277. ↩

- “The Gleaner,” 277. ↩

- “Real Bread,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 307–308. Regarding Christ’s availability in the Sacrament, Knox writes: “Infinite power, infinite goodness, makes itself infinitely available. Go to communion in some little country church, where you find yourself alone at the altar rails, or go to midnight Mass at Westminster Cathedral, and get sucked into the interminable queue which is slowly moving eastwards — it makes no difference. In either case the sacred Host which you are destined to receive contains the whole of Christ, all meant for you.” “Jesus My Friend,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 327. Knox was equally explicit and realistic about the Real Presence in the Precious Blood, although the circumstances of his preaching — often during the feast of Corpus Christi and also at a time when the reception of Holy Communion under both species by the laity was rare — made it prudent to speak more often of the Body of Christ. Implicitly invoking the concept of concomitance, Knox reminds his congregants, “Remember, too, that when we receive the sacred Host we are receiving the blood of Christ, that true loving-cup which he shared with his disciples before he went out to drain, alone, the chalice of his agony.” “One Body,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 345. ↩

- “First and Last Communions,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 336. ↩

- “A Priest For Ever,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 368. ↩

- “The Mirror of Conscience,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 385. Earlier in the same sermon, Knox calls to mind the occurrence of a priest catching sight of himself reflected in the paten: “It is the kind of distraction he can make good use of. Because he will do well to consider the contrast between what he sees on the paten, and what he meant (and was meant) to see there. He looked there to catch sight of a sinless Victim; he caught sight, instead, of a sinful priest. Domine, non sum dignus — how can this be worthy to receive that?” He also contrasts the Eucharist with Veronica’s veil (among other examples), which received the appearance of the Lord, without the reality. Ibid. ↩

- “The Mirror of Conscience,” 386. ↩

- “The Mirror of Conscience,” 385. See also “Holy Communion,” 138, for a similar use of the same image. Elsewhere, Knox uses a similar image, this time of the sun reflected in individual puddles of water, and draws out the following in consequence regarding the Eucharist, “In every single consecrated Host the whole substance of Christ’s glorified body subsists, and with it his soul and his divinity; when a hundred Hosts are consecrated, it is not one miracle that is performed, but a hundred miracles; and one was for you. When you realize that admirable condescension, that God made that one piece of bread become his own body and blood for your sake, then, perhaps, you will shrink back, and cry out with the centurion: ‘No, no, not that! I am not worthy that thou shouldest come under my roof, I who am only a creature, only one among so many millions of creatures, and that one so marred by imperfections, so stained with sin. A countless host of angels waits about thy throne, speeds this way and that to do thy bidding; send one of these, Lord, to give me the grace I need for this day, the strength I need to conquer these temptations; do not trouble thyself, Master, to come to me.’ But he will not have that, now. ‘I will come and heal him’, that is the method which, infinitely condescending, he has decreed for our sanctification. No secondary agent, no intermediary, shall communicate to us the influence our souls need; he will come to us himself. How he must love us, to want to do that!” “Prope Est Verbum,” 357. ↩

- “Self-Examination,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 296. ↩

- “First and Last Communions,” 334. ↩

- “The Divine Sacrifice,” 399. ↩

- “One Body,” 344. ↩

- Saint Thomas treats of this question in Summa Theologica III, q. 77, a. 1, concluding that the accidents of bread and wine which remain after transubstantiation do so by the divine power and not as belonging to a subject. Thomas does not use the word “inhere” but writes that the species of bread and wine “are not subjected in (subiecto in) the substance of the bread and wine, for that does not remain,” and neither are they “subjected in” the substance of Christ’s Body and Blood, “because the substance of the human body cannot in any way be affected by such accidents; nor is it possible for Christ’s glorious and impassible body to be altered so as to receive these qualities.” Thomas further explains in the second article of the same question that “dimensive quantity” (quantitas dimensiva) is first among the accidents, which after transubstantiation “God makes . . . to exist of itself,” and that the other accidents are in turn subjected in the dimensive quantity. Regarding transubstantiation in general, the Catechism of the Council of Trent affirms that “to explain this mystery is extremely difficult.” Regarding the specific relationship of the accidents of bread and wine to the substance of the Body and Blood of Christ after transubstantiation, the Catechism teaches, “For, since we have already proved that the Body and Blood of Our Lord are really and truly contained in the Sacrament, to the entire exclusion of the substance of the bread and wine, and since the accidents of bread and wine cannot inhere in the Body and Blood of Christ, it remains that, contrary to physical laws, they must subsist of themselves, inhering in no subject.” Catechism of the Council of Trent, trans. John A. McHugh, OP and Charles J. Callan, OP (Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, 1982) 252 and 255. ↩

- “Holy Communion,” 135. For Knox’s treatment of the concept of “mystery,” see also his Oxford sermon, “The Nature of Mystery,” University Sermons of Ronald A. Knox (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1963), 258–64. For Knox, a mystery is a truth or a reality that lies beyond the reach of human reason. Such mysteries have a reciprocal relationship with the theological virtue of faith. One needs faith to grasp the mysteries of Christianity, and mysteries are “the proper, the characteristic food of faith” (263–64). Perception of the mysteries of faith is also (and, of course, first) the result of grace. Knox describes a mystery as a “chink” in the “wall” of human thought, through which “the supernatural shines through” (260). ↩

- “Holy Communion,” 135. Knox also uses these parables to illustrate the divine power at work in the Eucharist in the sermons “Bread and Wine,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 346–52, and, in the same volume, “Novum Pascha Novae Legis,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 358–62. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 347. ↩

- Here he quotes the line of Richard Cranshaw’s poem “Aquae in Vinum Versae,” from his work Epigrammata Sacra: “Nympha pudica Deum vidit, et erubuit” (“the shame-faced water saw its Lord, and blushed”). Knox calls Cranshaw’s line “perhaps the most ingenious line in Latin poetry.” Yet it cannot be viewed as indicating merely what Knox refers to as “a miracle of transaccidentation.” “Bread and Wine,” 347–48. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 348. See also “Holy Communion,” 138. ↩

- “Holy Communion,” 137. In his commentary on Christ’s Bread of Life Discourse in John 6, Knox approaches the question of deception from another angle, affirming that Jesus does not speak of his flesh as food and blood as drink in a merely spiritual sense. Knox writes that Our Lord, “makes clear that this is food and drink which cannot deceive us. In a word, everything indicates that our Lord is not using metaphor, but is talking strictly sacramental language.” Ronald A. Knox, A New Testament Commentary for English Readers, vol. one (London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1953), 223. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 349. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 350. “Our Lord . . . would have us say to ourselves, ‘Yes, this is a wonderful miracle that he does in the Mass, to change the substance of bread and wine into the substance of his own body and blood, so that this body and blood is conveyed to the millions of the faithful by all the million Hosts of the world. But, after all, he did still more evident miracles while he lived amongst us, turned the substance and accidents of water into the substance and accidents of wine; multiplied the substance and accidents of five loaves of bread to feed a hungry multitude.’” ↩

- Knox refers to transubstantiation as “the greatest of all (Christ’s) miracles” in the sermon “Giving of Thanks,” 264. For a magisterial point of reference on the miraculous nature of transubstantiation, see Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, no. 46: “To avoid any misunderstanding of this type of presence, which goes beyond the laws of nature and constitutes the greatest miracle of its kind, we have to listen with docility to the voice of the teaching and praying Church. Her voice, which constantly echoes the voice of Christ, assures us that the way in which Christ becomes present in this Sacrament is through the conversion of the whole substance of the bread into His body and of the whole substance of the wine into His blood, a unique and truly wonderful conversion that the Catholic Church fittingly and properly calls transubstantiation. As a result of transubstantiation, the species of bread and wine undoubtedly take on a new signification and a new finality, for they are no longer ordinary bread and wine but instead a sign of something sacred and a sign of spiritual food; but they take on this new signification, this new finality, precisely because they contain a new ‘reality’ which we can rightly call ontological. For what now lies beneath the aforementioned species is not what was there before, but something completely different; and not just in the estimation of Church belief but in reality, since once the substance or nature of the bread and wine has been changed into the body and blood of Christ, nothing remains of the bread and the wine except for the species — beneath which Christ is present whole and entire in His physical ‘reality,’ corporeally present, although not in the manner in which bodies are in a place.” ↩

- “The Window in the Wall,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 245. ↩

- Earlier we saw part of Knox’s introduction to the sermon “Bread and Wine,” which is unfortunately undated but was among those preached at Corpus Christi, Maiden Lane. Knox explains that it is his purpose to present the Church’s theology of the Eucharist, and particularly that of transubstantiation, in such a way that his hearers will be able to understand and articulate their faith if they are questioned by “our Protestant friends” (346). For a balanced consideration of the distinction between Protestant theology and devotion, see “The Thing that Matters,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 300–301. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 348. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 348. ↩

- “Bread and Wine,” 348–49. ↩

- Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 279. ↩

- Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 279. ↩

- “The Hidden God,” Pastoral and Occasional Sermons, 380. ↩

This is an outstanding summary and very useful for prayer, contemplation and preparing for one’s homilies on the subject. Superb annotations. Thank you Father.