Pope Francis: The Legacy of Vatican II (Revised and Expanded Edition) by Dr. Eduardo J. Echeverria (Hobe Sound, FL: Lectio Publishers, 2019) 456 pages

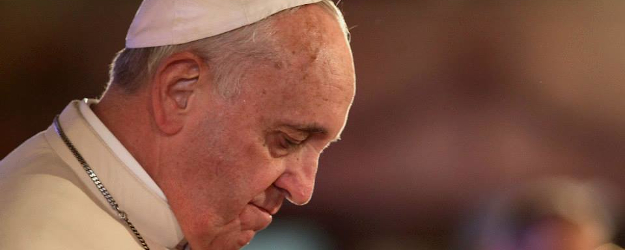

No one who has paid even the least amount of attention could fail to conclude that, whatever one may think of His Holiness Pope Francis, his pontificate has been marked by considerable controversy, administrative Vatican upheavals, and, some of his harsher critics may even say, scandal.

Of course, since he became the 265th successor of St. Peter in 2013, several books have been published about Pope Francis, ranging from a promotion of his positive spirituality for the sake of advancement in the life of Faith to the highly “critical expose” The Dictator Pope. Some books provide a serious examination of the ideas and life experiences that shape the outlook of Pope Francis such as Austen Ivereigh’s sympathetic The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope, published in 2015. Others, such as Massimo Borghesi, professor of philosophy at the University of Perugia, have sought to defend Pope Francis against accusations that he is an intellectual “light-weight” compared to his immediate predecessors in his 2018 book The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergolio’s Intellectual Journey.

Regarding an actual review of the papacy under Pope Francis, we might mention Karl Keating’s The Francis Feud: Why and How Conservative Catholics Squabble about Pope Francis, an analysis of three books highly critical of the papal style of Pope Francis: The Dictator Pope, already mentioned, Philip Lawler’s Lost Shepherd, and New York Times Catholic columnist Ross Douthat’s To Change the Church.

Pope Francis certainly has not been without his public critics, including some indeed very highly respected churchmen who have expressed grave concerns over Francis’s pastoral decisions, and even theological/doctrinal errors, most notably Cardinal Raymond Burke, who with three other prelates submitted dubia to Pope Francis, asking for clarification of Church doctrine in the wake of Francis’s post-synodal document Amoris Laetitia, and Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano’s famous letter accusing Pope Francis of supporting Cardinal Theodore McCarrick even after he had been informed of the now defrocked prelate’s sexual molestation of seminarians. Then there is the very recent vocalized concern of Bishop Athanasius Schneider, the auxiliary bishop of Astana, Kazakhstan, who believes Pope Francis is complicit in betraying Christ as the “only Savior of mankind” as Francis approves of a the Vatican-sponsored Higher Committee established to implement the Abu Dhabi document. This is the highly controversial “Document on Human Fraternity,” signed by Pope Francis, February 4, 2019, which stated: “The pluralism and the diversity of religions, color, sex, race, and language are willed by God in His wisdom.”

However, few if any books actually provide an in-depth examination of the theological foundation grounding the decisions and statements of Francis by which the Church is now guided under his papacy. Such an examination is much needed if we are to truly understand Francis and how he comes to the conclusions he makes that many find perplexing and even troubling in light of Catholic doctrinal tradition. A theologian is needed to unpack the theology of Francis. Eduardo J. Echeverria, Professor of Philosophy and Theology at Detroit’s Sacred Heart Major Seminary, in his work Pope Francis: The Legacy of Vatican II, has written an important in-depth analysis, and it can be characterized as nothing less than a theological tour de force.

What is especially interesting about Echeverria’s work is that the second edition is an about-face from the first work published in 2015. Professor Janet Smith writes in the preface to the second edition: “Echeverria maintained that Pope Francis’s thought could be interpreted to be in continuity with the tradition. But in the subsequent years, Francis has spoken in a way that has caused Echeverria to reassess his initial evaluation and be more wary of Francis’s ‘theological pluralism’.” Echeverria critiques Francis in comparison to the doctrinal pronouncements of, especially, Saint John Paul II and also those of Benedict XVI as these two popes guided the Church in the wake of Vatican II and sought to implement the reforms of the Council.

Echeverria’s work is a rich scholarly examination of Francis, meant for the serious reader and weighing in at a fairly hefty 392 pages, not counting the extensive bibliography. One will be hard pressed to find a more detailed and exhaustive analysis of the theological outlook of the current pontiff. If one wishes to probe the theological depths of the Francis pontificate, this book would be essential reading as it provides between two covers the road map by which one can understand this pope and appreciate how one can say, if not conclude with Echeverria, that Francis’s leadership is dominated by a troubling lack of clarity and a dangerous doctrinal rupture that leads to confusion. However, while Echeverria argues that Francis’s teachings are not in continuity with the Vatican II popes, this work treats Francis with great respect and is quick to be fair.

Pope Francis: The Legacy of Vatican II is divided into eight chapters, each followed by copious footnotes. The first may arguably be the most important, as it provides the primary key by which to judge whether the thought of Francis, and the practical consequences of his thought for the life of the Church, is indeed consistent with the doctrinal tradition. Here we have an intense examination of what is referred to as the Lerinian Legacy, the legacy upon which the Vatican II council Fathers relied, and was even articulated by St. John XXIII in his opening address to the council. The Lerinian Legacy refers to the teaching of a fifth-century Gaelic monk, Vincent of the Abbey of Lerins, who served as the congregation’s chief theologian. Vincent taught: “Let there be growth and abundant progress in understanding, knowledge, and wisdom, in each and all, in individuals and in the whole Church, at all times and in the progress of ages, but only with the proper limits, i.e., within the same dogma, the same meaning, the same judgment.” Echeverria goes on to explain that indeed “dogmas can develop” yet “they cannot change their fundamental meaning, i.e., the meaning and the truth-content embedded in the creeds themselves.” Echeverria as a theologian is very interested in the relationship between the essential meaning of doctrinal Faith and propositional Faith — how indeed the Faith itself is specifically articulated. How can the articulation change, perhaps be modernized, for instance, and yet be the same dogma “with the same meaning and the same judgment”? This is the test for any authentic development of doctrine — a possibility the Church accepts and which was indeed affirmed by Vatican II: specifically, for example, in two of the Council’s constitutions: Dignitatis Humane and Dei Verbum.

Echeverria points out that Francis in terms of doctrinal development relies on Vincent of Lerin, but leaves out, “overlooks” the qualifying Lerinian clause: “but only with the proper limits, i.e., within the same dogma, the same meaning, the same judgment.” Echeverria’s research into the mind of Pope Francis has forced him to conclude that Francis does not “affirm the permanence of meaning and truth of dogmas.” Echeverria makes this troubling statement:

In the first edition of this book I thought he did, but I now see more clearly that he has a difficult time affirming dogma’s permanence given his dismissal of abstract truth — that is, propositional truth — his reluctance to speak of absolute truth, and his theologico-pastoral epistemology with its attending principle that realities are greater than ideas.

Echeverria doesn’t mince words. He says he has come to accept that

Francis has contributed to the current crisis in the Church — doctrinal, moral and ecclesial — due to a lack of clarity, ambiguity of his words and actions, one-sidedness in formulating issues, and a tendency for demeaning Christian doctrine and the moral law.

However, Echeverria’s work must not in any way simply be assessed as a mere anti-Francis diatribe. Even if one wishes to defend all that Francis seeks to accomplish, and disagree with Echeverria, an honest evaluation of this book would conclude that it is a balanced, serious theological penetration that argues with scholarship why the Francis pontificate is concerning.

Besides the abbreviated application of the Lerinian Legacy, it is important to understand what is meant by “realities are greater than ideas” in the thought of Francis, as this is essential to his pontificate marked by a “Pastorality of Doctrine.” Realities go in two directions. There is the personal experience of believers, the existential situation in which they find themselves, upon whom it may be unrealistic to simply impose an inflexible doctrinal/moral proposition, which leads to a pastoral emphasis on what is termed “the law of gradualness,” in which the propositions are viewed as “ideals” to be achieved rather than commandments God expects His followers to live by, and by which they will be judged. Then there are the divine realities. Echeverria relies on Francis’s own writing to demonstrate the pope’s troubling conclusions when, for instance, based on the premise that “realities are greater than ideas,” we see its pastoral application. Francis states in his Apostolic Exhortation Gaudete et Exsultate (GE):

It is not easy to grasp the truth that we have received from the Lord. And it is even more difficult to express it. So we cannot claim that our way of understanding this truth authorizes us to exercise a strict supervision over others’ lives. Here I would note that in the Church there legitimately coexist different ways of interpreting many aspects of doctrine and Christian life.

For Francis the reality of God always remains beyond us and so, based on the same document, Echeverria shows doctrinal clarity is sacrificed to a “praxis-orientated theology” in which Francis in GE derides “those who long for a monolithic body of doctrine guarded by all and leaving no room for nuance”. Echeverria completely agrees with Francis when the pope declares in the Apostolic Consititution Veritatis Gaudium, “For the truth is not an abstract idea, but is Jesus himself.” Yet, as Echeverria shows with reliance on St. Thomas Aquinas’s exposition on the meaning of faith, faith is not only acceptance of the “divine Word Jesus Christ,” but the proposition that provides a proper Christology of who is this Christ! Thus, based on Aquinas, Echeverria shows that “our faith is both propositions and in the reality of the divine Word Jesus Christ.”

The book examines in depth the manner in which Francis’s emphasis on mercy as the first attribute of God causes the pope to push into the background law and justice, and Francis’s tendency to negatively evaluate the latter as mere legalism. Here Echeverria provides a lengthy discussion on the relationship between mercy and justice as taught by John Paul II in Dives in Misericordiea in comparison to Francis, who often improperly “pits gospel and law over against each other.” Yet in fairness to Francis, Echeverria shows restraint as he cannot accuse the pope of simply being a relativist or antinomian as Francis himself, despite his lack of clarity or consistent argument, refuses these views.

Echeverria rightly shows that one must first understand the pope’s emphasis on mercy over the law to appreciate the pope’s views on reception of Holy Communion being possible for divorced and remarried Catholics set forth in the controversial Chapter 8 of the 2016 post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia. Here the poor exegesis of Francis is on display as Echeverria explains the way in which Francis in a February 24, 2017, homily misrepresented Mark 10:1–12, in which Jesus corrects the Pharisees on the issue of whether it is legitimate for a man to divorce his wife. When the Pharisees confront Jesus to trick him with the question “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife?” Francis says that “Jesus doesn’t answer whether it is permitted or not.” Francis took the opportunity to lambaste what he called a strict morality based on casuistry — only concerned with what is permitted or not permitted. And while Francis may be right that Jesus “puts aside casuistry,” Echeverria points out, this is hardly the same thing as Jesus not answering the question. Jesus surely did answer the question, and he went well beyond the Law of Moses, declaring that divorce and remarriage is in fact adultery and he expects his followers to live marriage as it was first intended by God in the Beginning — that is, before sin!

Francis defended Amoris Laetitia by continuing his critical view of “the legalist” when, in a book of interviews, he said we must avoid a “uniformity of rules” and mocked those who criticize Chapter 8 as simply the folks who always just say “no, no, no,” and here even believes he is supported by the way Jesus responded to the Pharisees, when in fact Jesus was closing the loopholes that the Pharisees were intent on keeping open. Consistent with the book’s method, Echeverria contrasts the approach of Francis with the teachings of John Paul II and Benedict XVI — frankly, a section much longer than it needs to be to demonstrate that mercy and truth co-exist in the moral life as the Church is both Teacher and Mother. Indeed, one criticism of this work is that it could have benefited from a good editor to streamline the lengthy comparison sections which simply do not need to be absolutely exhaustive for Echeverria to make his point. However, having said that, whole sections of this book could stand on their own as helpful expositions of Catholic belief: for instance, Echeverria’s seventeen-page overview of the Catholic teaching on the meaning of marriage provided in the chapter that deals with, as it is titled, “The Controverted Chapter 8 of ‘Amoris Laetitia’.”

Other issues covered by Pope Francis: The Legacy of Vatican II: Pope Francis’s weak, relativistic ecclesiology; Francis’s emphasis on dialogue over evangelization, in a dialogue that, while the Pope affirms “one should not renounce their own ideas and traditions,” yet, on the other hand, neither should one “claim that they alone are valid and absolute,” which Echeverria argues tends in the direction of relativism. The author concludes here that at the very least Francis “does not seem to realize the implication of denying the uniqueness and absoluteness of Christian beliefs.” This indeed may explain arguably the most controversial gesture of the Francis pontificate, his signature on the February Declaration of Fraternity: “The pluralism and the diversity of religions, colour, sex, race, and language are willed by God in His wisdom, through which He created human beings.” Oddly, Echeverria — in a book that demonstrates in what way Pope Francis may be seen not to be in continuity with Catholic propositional Faith and the post–Vatican II popes — only refers to the Abu Dhabi statement in a footnote. Nonetheless, Echeverria does provide an in-depth analysis of the manner in which absolute truth claims of Christianity are dismissed by Francis for the sake of ecumenism and inter-religious dialogue. Also oddly absent in this volume is the way in which Francis altered the Catechism of the Catholic Church on the subject of capital punishment.

The final chapter provides a helpful discussion of the meaning of sensus fidei, often misunderstood, in which not only the hierarchy, the teaching Church, but the laity as well also “teach” in the sense that they dynamically express the lived Faith of the Church and contribute to its doctrinal understanding and development — but never of course without being anchored in Sacred Tradition, or by contradicting it. But Echeverria shows that Francis tends to use the sensus fidei as experience of the faithful, treating it as a spiritual capacity by which the “new” ways of the Lord are discerned. Thus in dialogue, the “listening Church” should be open to “change our convictions and opinions.”

The book is a serious examination of Francis’s approach to Church doctrine and pastoral application. Echeverria doesn’t hold back from weighty criticisms such as

Francis’s equivocation and lack of clarity about the status of doctrinal (propositional) truth in the Christian life, yet most of all because he emphasizes the aspect of mitigated responsibility in his moral theory, with a corresponding emphasis on the “law of gradualness” in his logic of pastoral reasoning, which despite Francis’s disclaimers to the contrary . . . arguably slips into the “gradualness of the law”. This slippage occurs because he seeks to create a moral space to justify the choices a person makes in certain problematic situations which do not objectively embody the moral law. He uses the language of moral ideals rather than a matter of rule-following, which suggests, as John Paul II argues, a regard of the moral law “as merely an ideal to be achieved in the future” rather than a consideration of it “as a command of Christ the Lord to overcome difficulties with constancy.” In Francis’s attempt to justify a person’s situation-specific choices in morally problematic situations, his logic of discernment teeters in the direction of situation ethics.

Evidence of this approach exists in the problematic pastoral conclusion of Francis in AL 303, where the pope states:

Yet conscience can do more than recognize that a given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel. It can also recognize with sincerity and honesty what for now is the most generous response which can be given to God and come to see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one’s limits, while yet not fully the objective ideal.

Echeverra’s probing and scholarly analysis provides strong arguments that lead to very disturbing conclusions, namely that the Francis pontificate represents on several levels a rupture rather than an authentic development of Catholic doctrine and application. The Echeverria book may be faulted for not confronting the defenders of Pope Francis, as several theologians have come forward to show, for instance, that paragraph 303 as it exists in the original Latin cannot be interpreted as Francis supporting situation ethics. But if Echeverria omits engagement with Francis’s defenders, it is perhaps a minor weakness, as his volume is already full and expansive.

For theological or even personal reasons, readers may very well prefer the precedence of mercy over an insistence on propositional truth, in agreement with Francis that such an insistence obstructs proclamation of the Good News. Nonetheless, this book does two things. Readers will understand first why Francis comes to the conclusions he makes and the emphasis he prefers, and secondly understand the arguments of those who have serious concerns about this papacy. In this volume Echeverria, who himself came to alter his view of Pope Francis, has made a valuable scholarly contribution to the corpus of books that critique this pope and the effect of the Francis papacy on the Church of Christ.

Eduardo J. Echeverria is Professor of Philosophy and Systematic Theology in the Graduate School of Theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary, the Archdiocesan seminary of Detroit, where he has taught for thirteen years. He is also a research fellow in the Theology Faculty of the University of the Free State, South Africa. Professor Echeverria obtained his Licentiate in Sacred Theology from the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum) in Rome. He received a doctorate in philosophy from the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Professor Echeverria is the author of Divine Election: A Catholic Orientation in Dogmatic and Ecumenical Perspective (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2016); Berkouwer and Catholicism, Disputed Questions (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2013), Vol. 24, Studies in Reformed Theology; “In the Beginning . . .”: A Theology of the Body (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2011); Dialogue of Love: Confessions of an Evangelical Catholic Ecumenist (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2010); and Slitting the Sycamore, Christ and Culture in the New Evangelization, Monograph, 87 pp., No. 12, Christian Social Thought Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Acton Institute, 2008).

Dr. Miller,

I appreciate your review of Professor Eduardo J. Echeverria critique of Pope Francis’ theology. He gives me a new understanding of honest opposition to Pope Francis. Your description of the length and depth of his work will probably mean I will not find time to read it. I was disappointed that he did not respond to those who support Pope Francis’ theological approach.

When I read Pope Francis I keep two thoughts in mind.

1. Pope Benedict XVI wrote: #27 Apostolic Letter on Church in the MIddle East : “It is not fitting to state in an exclusive way: ‘I possess the truth’.“The truth is not possessed by anyone; it is always a gift which calls us to undertake a journey of ever closer assimilation to truth. Truth can only be known and experienced in freedom; for this reason we cannot impose truth on others; truth is disclosed only in an encounter of love.”

2. Father Miguel Ángel Fiorito, Pope Francis’ spiritual director quoted Augustine’s luminous expression on the subject in De Doctrina Christiana: “Everything, in fact, is not exhausted when one gives it because if one possesses it without distributing it, one does not possess it as one should possess it.” (I, 1)[5]

It strikes me if one takes the position of Professor Eduardo J. Echeverria dialog as part of evangelization becomes difficult if not impossible. In some sense, if propositional faith is absolute, how can I discover and grow together with the other in a new understanding of truth. If St Thomas is the definitive approach to dogma, how do we enter into theological understanding based on a Confusion understanding of dogma?