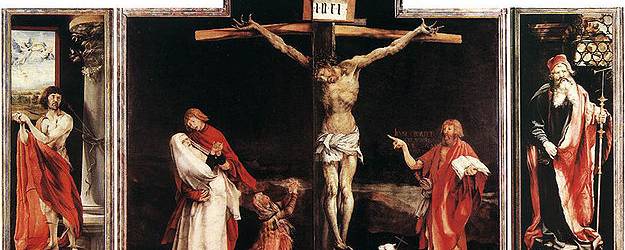

One of the most famous depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus is that of German painter Matthias Grünewald. Grünewald’s most recognized work appears on the center-front panel (when wings are closed) of his polyptych masterpiece, the Isenheim Altarpiece (early sixteenth century). The macabre scene famously depicts a frail, lanky, crucified figure of a bloodied and dead Jesus, blood trickling down from the postmortem wound on his side, with sores and wounds all over his emaciated body, gangly fingers awkwardly outstretched beyond the nails hammered through the palms of his hands, and his crowned head dangling lifeless almost below his seemingly dislocated shoulder.

At the time of its completion, it was one of the first realistic depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus; not that the figure of Jesus is realistic (the painting exaggerates and distorts in its imagery), but that the work expresses the grotesque reality of the extreme pain and suffering of the Roman crucifixion. Grünewald does not conceal or temper the absolute agony that Jesus must have experienced during his Passion and death as a result of the ruthlessly torturous scourging and execution by the very skilled Roman executioners.

For good reason then, the figure of John the Baptist in the painting is probably often neglected, perhaps with the exception of John’s prominently placed finger pointing at Jesus. At the very least, the words painted behind the Baptist are probably overlooked and less examined than the ghastly figure of Jesus on the cross, and rightly so. Yet there is John, placed anachronistically by Grünewald at the scene of the crucifixion, pointing at Jesus.

One might expect that the words behind the Baptist would read “Behold, the Lamb of God” given that there is a lamb at the feet of John which is holding a small cross and is itself bleeding into a chalice as John points at Jesus, and these are some of the most famous words that the Baptist ever uttered and are the words repeated during the Liturgy of the Eucharist today which memorializes and makes present the Passion and sacrificial death of Jesus on the cross; but they do not. Instead, the words painted behind him read: “Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui” [He must increase, but I must decrease].1 These are the words of the Baptist spoken in John 3:30 in response to one of John’s own disciples who tells John that all the people are instead now going out to Jesus to be baptized.

In this article, I will not offer an interpretation of Grünewald’s masterpiece or his depiction of John the Baptist; rather, I will use Grünewald’s portrayal of John, namely John’s act of pointing his finger at Jesus and the words written behind John, to assist me as I offer an interpretation of the priestly ministry of John the Baptist and to explain how this ministry can be lived out by our priests and bishops according to Benedict XVI.

Benedict explains that in John the Baptist, the entire priesthood of Israel and the Old Testament moves toward Jesus and is a pointer to, and prophecy of, Jesus and the proclamation of his mission.2 The Baptist’s father, Zechariah, is a priest from the division of Abijah and his mother, Elizabeth, is from the tribe of Aaron; because the service of priests in Old Testament law is connected with the tribes of the sons of Aaron and Levi, John the Baptist is indeed a priest who, as it was said, will not partake in wine or strong drink as was commanded of Aaron and his sons whenever they entered the tent of meeting.3 The priestly path to Jesus that is found in the Old Testament culminates in the person of John the Baptist who proclaims that, finally, the One who had been prophesied has arrived and that despite John’s own large following, this Jesus is the One who all should seek to follow, for it is John’s role only to show people the way to him.

In order to fulfill his specific priestly mission, John must decrease (“me autem minui,” as John says and as Grünewald painted). For any one of us, to decrease is a difficult thing; we desire to be heard and respected, and often want to be seen, recognized, praised, rewarded, and followed. But how much more difficult must this have been for the Baptist, whose own life was a miracle from God even from its very beginning. John’s father receives an angelic message about the birth of his son in the Temple during the liturgy (how appropriate for a priest whose son was going to be the final priest of the Old Covenant).4 Benedict demonstrates that the story of the annunciation of John’s birth is saturated with Old Testament language and references, namely to the miraculous births of Isaac and Samuel.5 God had promised Abraham that his elderly and barren wife Sarah would have a son — and not just any son, but the son of promise through whom the covenant would pass. God later intervened in the life of Hannah, also barren, whose prayer for a child was miraculously answered by God; she gave birth to Samuel.

Benedict states that John thus belongs to a line of offspring born through miraculous interventions of God.6 Benedict writes: “Because he [John] comes from God in this special way, he belongs completely to God, and hence he also lives completely for men;” but not without an important purpose, as Benedict adds: “in order to lead them to God.”7

Jesus responds to Pilate’s inquiry about whether or not he is a king saying: “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Every one who is of the truth hears my voice” (John 18:37). It is similarly said of John the Baptist that the specific reason he was born was to point to Jesus and to testify about the One who is Truth: “He [John] came for testimony, to bear witness to the light, that all might believe through him [Jesus]” (John 1:7). The precise reason that the Baptist came into the world was to convince everyone to look at Jesus just as Grünewald’s Baptist urges us to do, and as most of us probably reflexively do when encountering Grünewald’s crucifixion scene without first noticing the Baptist himself; this is the beauty and genius of Grünewald’s work.

Benedict explains that John is filled with the Holy Spirit from his mother’s womb and lives permanently in the tent of meeting; he is not a priest at certain moments, but he is a priest always and with his entire existence.8 The ultimate purpose of his entire priestly life is to point to Jesus. His mission began even in the womb of his mother wherein he leapt in the presence of Jesus who had been formed in the womb of his mother Mary six months after John was conceived, as if to prefigure what the Batist later mysteriously declares: “After me comes a man who ranks before me, for he was before me” (John 1:30).9 The prologue of John’s gospel attests to the special purpose of the life of the Baptist who, like Jesus, was “sent from God” (John 1:6), which denotes a divine mission which gives meaning to the Baptist’s entire existence.

Years later, throughout his own public ministry, John attracts many followers and preaches about repentance, conversion, and judgment. As the Gospels report, many came from all over Judea and from Jerusalem to the Jordan River to be baptized by John. Benedict says that John the Baptist must have produced an extraordinary impression in that highly charged political-religious environment and because the Jewish people believed that there was finally another prophet operating among them; God was once again acting in history.10

Benedict writes that there is no reason to dismiss Mark’s description as an exaggeration that “they went out to him all the country of Judea, and all the people of Jerusalem” on pilgrimage to be baptized by John.11 John was an enigmatic figure who touched the lives of many people and attracted many followers who came to listen to him and to be baptized; and yet, despite his having such a following and such power, John declared that he “must decrease” and he announced that all who came to him should look to Another for the ultimate message about God and salvation, and that they should turn to that One and follow him instead. This again must have been all the more difficult given the praise that Jesus heaps upon the Baptist: “Truly, I say to you, among those born of women there has risen no one greater than John the Baptist” (Matt 11:11).

If John the Baptist is a priest — the one who connects the priesthood of the Old and New Covenants — then how do priests today live out what might be called the Baptist dimension of their particular ministerial priesthood? What does it mean that a priest must decrease and that Jesus must increase? What does it mean to always point to Jesus, as Grünewald’s Baptist always does? After all, Jesus is the priest par excellence who serves as the supreme exemplar; and at the most important moments of their priesthood, priests act in persona Christi. Most priests (and most Christians, for that matter) who look at Grünewald’s crucifixion scene thus perhaps rightly see themselves in the figure of Jesus rather than in the figure of John. What then does the priesthood of John the Baptist mean for those who act in the person of Christ but who should also perform the priestly duties of the Baptist?

To always point at someone else is at the same time to always point away from oneself. The symbolic imagery obviously denotes humility. Benedict stresses that priests must preach Jesus, not themselves. In his homily at the 2008 Chrism Mass, during which priests renewed their ordination promises, Benedict said: “[As priests] we do not preach ourselves, but him and his Word, which we could not have invented ourselves. We proclaim the Word of Christ in the correct way only in communion with his Body.”12 Similarly, he says:

The officeholder [priest] ought to accept responsibility for the fact that he does not produce things himself but is a conduit for the Other and thereby ought to step back himself . . . . He should be in the very first place one who obeys, who does not say ‘I would like to say this now,’ but asks what Christ says and what our faith is, and submits to that . . . . When [priesthood] . . . is lived correctly, it cannot mean finally getting one’s hands on the levers of power but, rather, renouncing one’s own life project in order to give oneself over to service.13

The mission of priests is to always point to Jesus — to preach and teach what Jesus taught (and what the Church has taught in his name), and not what they want to teach. In an age of celebrity priests and social media priest-phenoms, it is all the more important for priests today to exercise the humble priesthood of the Baptist and to ensure that in their preaching, teaching, and social media posting, they are always pointing to Jesus and preaching His message, not theirs. Ultimately, priests must be more concerned with producing followers of Jesus than followers on Twitter or Facebook.

Priests should ask themselves: Where does this teaching come from? Does it come from Jesus, or does it come from me? Is it something new, or is it something that is found in, or at least supported by, the magisterial teachings that the Church has proclaimed over the last 2000 years and which contain the faithful message of Jesus? Jesus’s words from John cited above are worth repeating: “Every one who is of the truth hears my voice.” Whose voice do we hear when priests and others preach, teach, write, and theologize in the name of the Church? If it is not Jesus’s voice, then it is not Truth.

This is perhaps one of the very good reasons why we should never give or hear applause after homilies in the Mass. While all of us in the pews hope to hear well-delivered and inspiring homilies, we must always remember that what is most important is that we hear the voice of Jesus and His message. Applause and other outward forms of praise following homilies during the Mass would give the impression that priests themselves deserve the credit for the Truth they are proclaiming. We should instead hold our applause for the moment we enter into heavenly glory (God willing) and see God “face to face” — the face of the One who should be the voice behind all preaching.

Benedict writes:

In proclaiming the faith . . . every priest speaks on behalf of Jesus Christ, for Jesus Christ. Christ entrusted his Word to the Church. This Word lives in the Church. And if I accept interiorly the faith of this Church and live, speak and think on the basis of it, when I proclaim Him, then I speak for Him . . . . The important thing is that I do not present my ideas, but rather try to think and to live the Church’s faith, to act in obedience to his mandate.14

When Jesus was teaching in the Temple, he was asked: “By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority” (Matt 21:23)? Jesus first refuses to answer, saying: “Neither will I tell you by what authority I do these things” (Matt 21:27); but later he tells the disciples: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations . . . teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Matt 28:18–20). Jesus is granted authority to teach by God (and, of course, he is God) and it is this teaching sourced in God that the disciples must transmit, not their own teachings.

Similarly, we hear in John: “‘How is it that this man has learning, when he has never studied?’ So Jesus answered them, ‘My teaching is not mine, but his who sent me; if any man’s will is to do his will, he shall know whether the teaching is from God or whether I am speaking on my own authority. He who speaks on his own authority seeks his own glory; but he who seeks the glory of him who sent him is true, and in him there is no falsehood’” (John 7:15–18).

Those who preach Jesus speak Truth, and it is His voice we hear; those who speak on their own authority and seek their own glory only hear their own voice, and in their teaching is falsehood. The priest who always points to Jesus and says, “My teaching is not mine, but his who sent me” is living up to God’s commandment to make disciples of all nations, and is fulfilling the priestly duties of John the Baptist. Thus, what Benedict says in the context of a discussion of the priest’s role in the sacrament of penance and reconciliation can be applied to the priest’s roles as preacher and teacher: “It is much more necessary that the priest be willing to remain in the background, thus leaving space for Christ . . . . The priest certainly does not draw his authority from the consent of men but directly from Christ,”15 i.e., the priest must decrease and Jesus must increase because he has true authority.

If to preach Jesus is the Baptist mission of the priesthood, then what is the exact content of that preaching? It certainly includes all that Jesus taught and handed on to the Church in its 2000-year history, but the core of that teaching must be Jesus himself. Benedict has often argued that the absence of God and the loss of transcendence are the sources of the greatest crises of the modern, materialist era, and they seem to have had a detrimental impact on the art of preaching and teaching the faith as well. He writes:

What role does God really play in our preaching? Do we not normally avoid the issue and shift to matters that we deem more “concrete” and more urgent — to political, economic and psychological questions . . . ? We think that everyone knows about God already, and that the subject of God has little to say about our everyday problems. Jesus corrects us: God is the practical, the realistic topic for man . . . . We think that God is too far away, that he does not reach into our daily life; so we say to ourselves, let’s speak of close-at-hand, practical realities. No, says Jesus: God is present, he is within call. This is the first word of the gospel . . . . This has to be said to our world with completely new vigor on the authority of Christ.16

To preach Jesus means to preach about God who is always present and is the most practical topic even in the modern era. To preach Jesus means to preach about God-incarnate — Jesus — and his message that is contained in the gospels, the core of which is the double-foci on the ever-present God and salvation, all on the authority of Jesus himself.

Later in John we again hear Jesus declare the source of his teaching: “Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father in me? The words that I say to you I do not speak on my own authority; but the Father who dwells in me does his works” (John 14:10). The more interesting element to note here is the request that prompted Jesus’s words: “Philip said to him, ‘Lord, show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father; how can you say, ‘Show us the Father?’’” (John 14:8–9).

Here, Jesus responds by essentially doing exactly what Grünewald’s Baptist does — he points to Himself! The teaching he provides comes from the Father, and he and the Father are one, and those who see Jesus also see the Father, and they now know where Truth comes from. When a request is made: “Show us the source of your teaching,” priests and others who teach in the name of the Church (educators and theologians) must be able to point to Jesus in whom the Father and Son are one. They must be able to point to the Jesus that has been preached authentically by the Church over the past 2000 years; if they have to point to themselves, other persons, or more generally to the zeitgeist, then they are by necessity not pointing at Jesus.

If the Baptist’s ministry is a necessary element of the priesthood, then this humble approach to teaching and preaching Jesus and the faith applies in a particularly important and supreme way to the ministry of the bishop, who, the Second Vatican Council proclaimed, is “marked with the fullness of the sacrament of Orders [and] is ‘the steward of the grace of the supreme priesthood.’”17 As they are shepherds of the Church and successors to the apostles, “he who hears them, hears Christ,”18 or at least he ought to hear Christ and not the bishops and whatever they themselves want to teach and preach. Bishops are not ordained to their office to wield levers of power to enforce their agendas. They are called to step back and allow Jesus to speak through them so that God’s agenda may be fulfilled, and they must do so in accordance with the previous magisterial teachings of the bishops and the Church through whom Jesus has already spoken, because their “episcopal consecration . . . confers the office of teaching . . . which, of its very nature, can be exercised only in hierarchical communion with the head and the members of the college,”19 both past and present, i.e., they cannot individually or in small groups, national conferences, or synods teach with authority or infallibly on their own but must remain in communion with the entire apostolic college since its inception. “Among the principal duties of bishops, the preaching of the Gospel occupies an eminent place. For bishops are preachers of the faith, who lead new disciples to Christ, and they are authentic teachers, that is, teachers endowed with the authority of Christ.”20

Given their special roles of teaching and preaching Jesus, bishops should be more devoted to the humble ministry of the Baptist than even their priest-cooperators, not only because of the great responsibilities they have for transmitting and explaining the faith, but because of the harm they can inflict on the Church if they pursue their own agendas. As Benedict says, they must renounce their own life projects and give themselves over to the service of Jesus. John the Baptist’s entire life project, even from his mother’s womb, was service to Jesus, and in everything he did, he pointed away from himself, and at Jesus.

- All Scripture references are from the Revised Standard Version unless quoted from within another work. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives, trans. Philip J. Whitmore (New York: Random House Large Print, 2012), 32. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 31–32. See Luke 1:15, “He will be great before the Lord, and he shall drink no wine nor strong drink,” and Lev 10:9, “Drink no wine nor strong drink, you nor your sons with you, when you go into the tent of meeting.” ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 34–36. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 37–39. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 39. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 39. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 39–40. ↩

- Benedict, The Infancy Narratives, 45–46. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, trans. Adrian J. Walker (New York: Doubleday 2007), 15. ↩

- Benedict, From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, 15–16. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Chrism Mass: Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI (Vatican City: March 20, 2008), available at https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20080320_messa-crismale.html. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Salt of the Earth: Christianity and the Catholic Church at the End of the Millennium, An Interview with Peter Seewald, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997), 192–193. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Light of the World: The Pope, the Church, and the Signs of the Times, A Conversation with Peter Seewald, trans. Michael J. Miller and Adrian J. Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2010), 7. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger and Vittorio Messori, The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church, trans. Salvatore Attanasio and Graham Harrison (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), 56–57. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Gospel, Catechesis, Catechism: Sidelights on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 41. ↩

- Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium (Vatican City: November 21, 1964), §26. ↩

- Lumen Gentium §20. ↩

- Lumen Gentium §21. ↩

- Lumen Gentium §25. ↩

Recent Comments