When speaking to his son, King David reminds Solomon what it takes to succeed as king: “I am about to go the way of all the earth. Be strong, be courageous [לְאִֽישׁ], and keep the charge of the Lord your God, walking in his ways and keeping his statutes, his commandments, his ordinances, and his testimonies, as it is written in the law of Moses, so that you may prosper in all that you do and wherever you turn” (1 Kgs. 2: 2–3, [Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition], emphasis added). לְאִֽישׁ, typically translated as “be courageous,” is more precisely translated as “be manly.” Thus, King David sees masculinity as a necessary component to flourishing in leadership. Similarly, Saint Paul, in his letter to the Corinthians, exhorts the Corinthians to “ἀνδρίζεσθε” — “act like men,” in order to be faithful followers of Christ and leaders in the Church, and like לְאִֽישׁ, is typically translated as “be courageous” (1 Cor. 16:13). Only when Solomon forgets David’s advice does his life come to a crooked end. Only when Christians fail to live Saint Paul’s advice does condemnation come. Society, having forgotten this advice, now has men living in a collective identity crisis, leading many to an unfortunate end.

In years past, seminaries could safely presume a basic foundation in Christian identity and formation of virtue within the culture. That is no longer the case; young men are forced to find authentic masculine virtue for themselves. Young priests now come into priestly formation and ministry from a society that often lacks awareness or acceptance of authentic masculinity, and it is becoming more common that priests’ views of masculinity are skewed because of these experiences. This masculine identity crisis has occurred because social narratives on gender and marriage have shifted away from traditional Christian principles. Social dialogue questions the worth of traditional masculine virtue, often considering it toxic and, thus, undesirable. This social dialogue targets the mental habits of choice and beliefs in young men and women, becoming so powerful that it can shape people’s sense of reality,1 especially developing a false sense of authority over one’s ability to “self-create” gender and its norms.2 This is the hotbed of social confusion and hatred young priests have come through to their priestly identity and ministry.

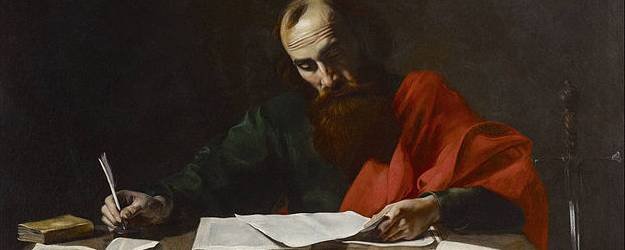

To confront this crisis, providing a robust, biblical view of masculine identity is critical for priests engaged in ministry. Using Saint Paul’s letters gives us one avenue to do just that. Throughout his writing, Saint Paul establishes what might be considered a “masculine genius,” borrowing terminology from Saint John Paul II.3

This article sketches what Saint Paul sees as unique masculine virtues by exploring passages that refer to specific and traditional male roles. Because of the breadth of Saint Paul’s material, some specificity is required. Ἀνήρ, which is the root of Saint Paul’s exhortation to be manly and is the common word meaning “man,” carries several connotations within the whole of Sacred Scriptures. Generally, four meanings emerge: 1) a “human person” (male or female), 2) a husband or father; 3) a grown adult male, or 4) one who is mature (as opposed to a child). Saint Paul uses these connotations, and each intent carries specific identifiers specifically for males or identifiers meant for any Christian, male or female. This article looks at three conventional masculine roles that Saint Paul envisions as possessing unique virtues valuable for supporting priestly identity: the virtues of being a Christian husband, father, and soldier engaged in spiritual warfare. Through these, a vision of positive masculine identity emerges.

Before exploring these three virtues, it is worth touching on Saint Paul’s general understanding of the body and its purpose. Writing to the Corinthians, he reminds them, “The body is meant not for fornication but for the Lord, and the Lord for the body” (1 Cor 6: 13b). The body is meant for the Lord. This is a critical assertion. Being masculine or feminine is designed to be directed toward goodness because it is of God. To be masculine and to live and act in our masculinity is to live for the Lord. Nothing is diminished, harmed, or obscured by being and acting as men; the opposite is true. We honor God and his purpose when we accept and live in our bodies as men. We flourish in our ministry and spiritual and psychological health when fully embracing godly masculinity. To be a man is good and holy.

Although Roman Catholic priests are called to chaste celibacy, Saint Paul’s words to husbands have immense value for the priest’s relationship with the Church, thus significant to this article. Upholding a traditionally masculine role, Saint Paul asserts that a husband is called to be the head of his wife and family (1 Cor. 11:3), and like Christ as the head of the Church, the husband is to lead his wife, who is to submit to him, for the sake of her sanctification and protection (Eph. 5: 25–33). However, this authority is not to be tyrannical or absolute.

In contrast to the context of the Roman empire of Saint Paul’s time,4 Saint Paul expects there to be a mutual obligation between husband and wife, emphasizing absolute equality and mutual submission: “For the wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does; likewise the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does” (1 Cor. 7: 4). This mutuality emphasizes the one-flesh union of man and woman for the sake of both their sanctification. Saint Paul understands masculine authority as self-gift by imitating Christ, who is head but also sacrifice, emphasizing the masculine virtue of authentic leadership, which is self-sacrificial and mutual.

The early Church’s reflection highlighted this reality; while the husband has authority over his wife, it was shaped by mutual fidelity, self-control, and self-giving.5 In modern reflections, Saint John Paul II likewise asserted that man, as a husband, only truly knows himself in “reciprocal enrichment,” leading to total communion.6

A priest should see himself similarly; his masculine leadership is a bridge and help rather than an obstacle. As a pastor, he will be called the “head” of his community, but he must lead as Christ leads as the head of the Church, his bride. A pastor must learn total self-sacrifice and submission to his bride, who holds a specific authority over him by holding him accountable to his mission — the true nature of being submissive. The priest, as masculine, must live in “reciprocal enrichment”7 with the Church as his bride. Through the working of the Holy Spirit, the two become one flesh.

Fatherhood for Saint Paul, which shares the virtues of a husband, has a clear source, responsibility, and method supporting various traditional masculine virtues. First, Saint Paul sees himself as the spiritual father of many communities (e.g., the Corinthians and Thessalonians), which he became through preaching the Gospel (1 Cor. 4:15). This spiritual fatherhood, engendered through preaching and adoption, is authoritative but not oppressive, e.g., “And, fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord” (Eph. 6:4). Saint Paul says that he desires, and so each father should desire, to exercise authority in “gentleness,” (1 Cor 4: 14–15, 21)8 recognizing a desire for “affectional warmth and challenge.”9 The father is called to exhort, console, and affirm his children so they may live in the righteousness of God.10

The spiritual writer Father Jacques Philippe, writing on spiritual fatherhood, states that a father’s primary responsibility is to instruct his children in the truth of God.11 He does so, he continues, through exhorting, disciplining, and admonishing his children in a “mission of encouragement.”12 Saint John Paul II similarly teaches that fatherhood contains a responsibility to impart moral uprightness to his children.13

A pastor is called to take on this virtue of gentle but firm teaching of spiritual children, which he “adopts” through his missionary efforts of proclaiming the Gospel. He is to exhort, admonish, and encourage in gentleness for the salvation of their souls and everlasting life. The priest’s spiritual children, men and women of his parish, are to be cared for in this way as a virtue of masculine authority: teaching and fatherliness.

Although a description for all Christians, the imagery of a soldier is one of the more prominent examples of masculine identity, relying on classic images of masculine strength and courage. Being a Christian soldier highlights each Christian’s need to engage in spiritual warfare, in which, as the Church understands, man finds himself “in the midst of the battlefield” where he must “struggle to do what is right . . . at great cost to himself, and aided by God’s grace.14 Saint Paul uses striking imagery to describe what kind of spirit (1 Tim. 1:7) the Christian soldier must have, what manliness is (1 Cor. 16:13), and how one prepares for battle (e.g., Eph. 6: 13–17). These three principles provide a valuable backdrop to the masculine virtue a priest is called to possess.

Saint Paul succinctly tells his listeners that, in Christ, God has not given us a spirit of timidity but rather a spirit of power and self-control (1 Tim. 1:7). This timidity is cowardice, an unwillingness to face challenge or suffering.15 This cowardice is the opposite of what Saint Paul sees as manliness in his first letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 16:13), where he says they are to be ἀνδρίζεσθε, that is, courageous. As he will describe, this courage means to be strong, watchful, and firm in the faith (1 Cor. 16:13–14). The need for courageous action exists because the Christian people will be beset with challenges from both the world and evil spirits (e.g., Eph. 6: 12–13).

Like any soldier, one must be equipped and trained for battle (2 Tim. 3: 16-17). Saint Paul is remarkably descriptive in this. One is first equipped through conversion to Jesus Christ, righteousness, and holiness of the truth.16 This equipping provides spiritual armor and weapons against the enemy, guaranteeing victory.17 For example, the sword of the Christian soldier is the preaching of the Gospel, which is the protection of peace already established by Jesus Christ. Armor, among various kinds, is the “breastplate of righteousness” (Eph. 6:14). This breastplate is living in uprightness and integrity of life. In all of this, however, Christians must know that the power of fighting does not belong to the individual Christian’s strength but the power of Christ.18

According to Saint Paul, being manly means embodying courage as an identity for fighting against evil through integrity of life, which has been supported by the preaching of the Gospel, righteous actions, and an awareness that Christ’s power is the force behind his actions. Masculine virtue is a willingness to be steadfast in the faith, watchful of himself and others, and courageous in the face of death, not only for himself but those who have been entrusted to him.

Saint Paul’s vision of masculine virtue articulates the image of pastoral activity: a willingness to defend his spouse and children as a warrior defends his country. The pastor must equip himself with integrity, good works, and steadfastness in the face of danger, possessing not a spirit of timidity but great courage and being willing to strike at all evil with the sword of the Gospel. The pastor must also recognize that the excellent work done defending against the world and evil spirits is only possible because of Christ’s grace.

As sketched here, what can priests inherit that supports their masculine identity and virtue? In the face of social pressure to empty masculinity of its power and purpose, the clergy needs support in developing and maintaining a biblically based vision of masculine virtue. Saint Paul provides that robust, biblical view in the face of this increasing pressure. We priests, taking Saint Paul’s exhortation to ἀνδρίζεσθε, “act like men,” seriously, will grow not only in psychological well-being but in spiritual fortitude and peace.

Collecting Saint Paul’s thoughts, we come to a masculine priestly identity where a priest is called to move from self-preoccupation to a gift of self that desires the welfare of others physically and spiritually. Likewise, the priest is called to foster an appropriate “nuptial meaning of the body”19 that leads to a gift of self. Last, he must submit himself, in total faith and communion, with the magisterium and his parish community, reflecting that “reciprocal enrichment”20 that Saint John Paul II emphasized. As the Christian husband must have the virtues of self-giving, control, and mutual fidelity, so must the priest. The priest must also be affirmed in his role as head and leader, as Christ is the head and leader of the Church. Although called to chaste celibacy, the priest must possess the virtues of masculine spousal living as necessary for his identity and mission.

In like manner, a priest is called to the virtues of fatherhood. A pastor takes spiritual initiatives, directs a community toward action and spiritual growth, and is willing to be a man of complete communion. Similarly, he is called to demonstrate that he has the capacity for the public witness of the faith as the source of his ministry. Saint Paul sees fatherhood in similar ways. A spiritual father’s sense of responsibility is for his children’s salvation formed through preaching, gentle authority, and the public witness of the faith in his teaching and exhortation.

Rather than diminishing it, the priest is called to boldly adopt a vision of being a spiritual soldier, called to be a man of solid moral character with a well-defined conscience and capable of conversion to Christ. A priest must show vigilance and authority over his body, be open to correction and accountability, and have discipline in public and private prayer by developing a personal relationship with Christ, all weapons in the fight against evil. The essential virtues that Saint Paul emphasizes are self-control (1 Tim. 1:7), firmness of faith (1 Cor. 16:13–14), and pursuing holiness through the integrity of life (Eph 6:14). This is done, in Saint Paul’s vision, by equipping oneself through conversion in Jesus Christ (2 Tim. 3:16–17).

Saint Paul’s vision of masculine virtue is vital for supporting priestly ministry by helping the priest develop a true masculine identity capable of entering, engaging, and persevering in his ministry. His vision corrects the various social distortions of masculinity and provides, borrowing Saint John Paull II’s expression, that “masculine genius” desperately needed today. Identity is a critical factor in developing a healthy personality and well-being. Properly addressing the positive realities of masculine identity in the context of priestly ministry allows for genuine flourishing. In this short article, what is at stake is understanding and accepting a proper masculine identity that retains a proper personal wholeness and in which one’s body is treated with dignity and meaningful purpose. A priest capable of seeing himself as possessing a positive and meaningful identity, who can articulate an account of that identity as he is formed, and who can operate from that identity will have a more substantial base for psychological and spiritual well-being. Saint Paul’s vision of masculine identity provides that rich theological reality where a priest can grow and flourish.

- Chad Ripperger, Introduction to the Science of Mental Health (Sensus Traditionis Press, 2022). ↩

- Paul C. Vitz, William J. Nordling, and Craig Steven Titus, A Catholic Christian Meta-Model of the Person: Integration with Psychology and Mental Health Practice (Sterling, VA: Divine Mercy University Press, 2020), 67. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2006). ↩

- Ben Witherington, Conflict and Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians (Grand Rapids, MI: Carlisle, 1995). ↩

- Judith L. Kovacs, 1 Corinthians Interpreted by Early Christian Commentators (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2005), 179–180. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 165. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 165. ↩

- Kovacs, 1 Corinthians Interpreted, 81. ↩

- Linda Mckinnish Bridges, 1 & 2 Thessalonians: Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Pub, 2008). ↩

- Nathan Eubank, First and Second Thessalonians: Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2019), 62–63. ↩

- Fr. Jacques Philippe, Priestly Fatherhood (Strongsville, OH: Scepter Publishers, 2021), 34. ↩

- Philippe, Priestly Fatherhood, 100. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 626–628. ↩

- Catholic Church, Catechism of the Catholic Church: Revised in Accordance with the Official Latin Text Promulgated by Pope John Paul II (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2000), §409. ↩

- Luke Timothy Johnson, The First and Second Letters to Timothy: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 2001), 385. ↩

- The Second Letter to the Corinthians, the Letter to the Galatians, the Letter to the Ephesians, the Letter to the Philippians, the Letter to the Colossians, the First and Second Letters to the Thessalonians, the First and Second Letters to Timothy and the Letter to Titus, the Letter to Philemon, in the New Interpreter’s Bible, Volume XI (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2000), 457–464. ↩

- The New Interpreter’s Bible, Volume XI, 457–464. ↩

- Frank Gaebelein and J. D. Douglas, eds., The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Ephesians – Philemon, Vol. 11 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1978), 87. ↩

- National Conference of Catholic Bishops, The Program of Priestly Formation (Washington, DC: NCCB, 1971), 6th ed, 89. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 165. ↩

Christus Resurrexit !

Reading your article on the manliness of priests and christian men, there are many fine points and analogies. In Diaconate Formation, I shall strive to incorporate the concrete points of manliness.

. However, what would St. Paul say about the priest , Deacon or Christian man who ,also participates in sports such as;, wrestling, boxing , judo or running?

Blessings! St. Paul uses physical competition and training as an analogy for the Christian life. Consider 1 Corinthians 9: 24-27: “Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. So I do not run aimlessly, nor do I box as though beating the air; but I punish my body and enslave it, so that after proclaiming to others I myself should not be disqualified.”

In an age where manual labor is not as common of a profession for men as it once was, physical exercise and appropriate sports are valuable tools in learning virtue. The key, I believe, is the telos of it, is it for vainglory, pride, or punishment? Or is it for mental and physical training which can be translated to spiritual growth?

This article articulates what is needed today for an urgent protection of the Catholic priesthood. The author’s use of “masculine genius.” most apt, continues as he includes St. John Paul II’s principles on masculinity. King David, I add, is a priest, a point author Brant Pitre brings out in his book, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist. Also, St. Edith Stein writes in her Essays on Women about the masculinity alluded to by Fr. Huard. I appreciated the reference to spiritual warfare, which is increasingly needed today. Thank you to Father, and I wonder if we could have an article specifically on the effects of contemporary emasculating of our priests.