If you ask laypeople why preaching in the Catholic Church is disappointing, they’ll usually give some variation on the answer, “Well, there’s a priest shortage, so priests are really busy, so they probably don’t have much time for preaching.” That makes sense, until you consider that the priest shortage has only been around since about the 1970s,1 but Pope Benedict XV published Humani Generis Redemptionem in 1917 — clearly because he saw a problem with preaching.

Writings like Benedict’s suggest there’s something deeper and more entrenched in the Church inhibiting the development of good Catholic preaching. So a few years ago, I decided to find out what that might be: I organized interviews with Catholic priests that focused not on what they preach about, but their training in preaching, how they prepare preaching, how they feel about preaching, how they balance preaching with their other responsibilities and the need for rest/relaxation, and so on. After just 43 interviews, I had some very clear answers to the question, “Why is preaching well so hard for Catholic priests?”

In 2023, I published those answers in a book with extensive quotes from the priests themselves to illustrate not just what they do when it comes to preaching, but why. Below, I adapt for HPR readers one of the early chapters of the book that gives a broad overview of what I found.

There Are Three Kinds of Preachers

Early on in our conversations, I noticed stark differences in the beliefs and attitudes priests expressed about their work in general and preaching work specifically, particularly their relationship to the Holy Spirit in preaching. Eventually, it became clear that what a priest believes about these things influences three other, equally important things: how he prepares and delivers his preaching, how he interacts with preaching feedback, and how at peace (or not) he is with preaching.

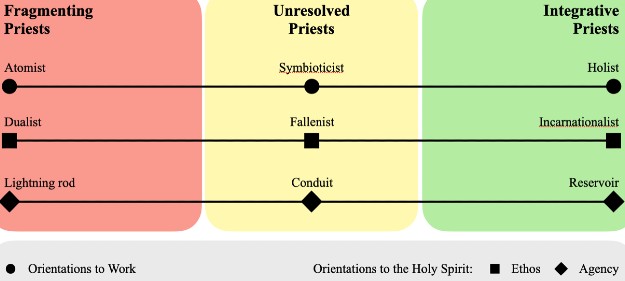

To simplify these differences, I developed a collection of “continua” that capture the range of priests’ orientations to work and to the Holy Spirit, then brought together the most common orientations in three “preacher profiles.” All of these things are visible in the figure below, but let’s break down what they mean there.

Orientations to Work and the Holy Spirit in Preaching

Three Continua

The three continua represent the dimensions on which priests differed:

- The orientations to work continuum captures the relationships a priest perceives (or not) between the diverse streams of work — administrative, pastoral, preaching — that he engages in every day.

Orientations to the Holy Spirit break into two continua:

- The ethos continuum captures how necessary and/or desirable a priest believes it is to reveal his own life experience and personality in preaching.

- The agency continuum captures how much agency a priest feels he ought to seize in preaching relative to the Holy Spirit.

Three Positions on Each Continuum

The middle, left-most, and right-most points on the continua bear strong similarities to one another across continua, both in the beliefs/attitudes they capture and in how they influence a priest’s preaching practice and personal wellbeing. These similarities are captured in Figure 1 by colored blocks.

- Unresolved priests struggle to reconcile perceived tensions in their work (in general and in preaching specifically), which can leave them feeling conflicted, confused, guilty, stressed, exhausted, and burned out. This is the most painful point on all three continua — and it’s where the vast majority of priests sit.

- Fragmenting priests think in terms of compartments, divisions, separations, distinctions, either/or relationships, and so on, which helps them to resolve the tensions most priests struggle with and so reduce their own stress, exhaustion, burnout, etc. — apparently, however, at the expense of good preaching. Only one priest I interviewed was an extreme fragmenter, but two others came close, and many others referred to priests they know with fragmenting tendencies.2

- Integrative priests are exactly the opposite of fragmenters: They’re strong both/and thinkers who view everything as a unified, indivisible whole, which also resolves for them the tensions most priests feel in their work — but in a way that appears to support good preaching. Again, only one of the priests I spoke with was strongly integrative across all three continua, but several others came quite close to him.

Three Preacher Profiles

If you put the three unresolved orientations from the three continua together, you get the average Catholic priest. If you put the three fragmenting orientations together, you get a priest who horrifies most of the men I spoke with. If you put the three integrative orientations together, you get a priest that most of my participants (and probably most other priests, too) would swear is a fictional character.

This is precisely what the “preacher profiles” do, and when priests read them, they invariably recognize “that guy” — or elements of him, at least. In reality, most priests don’t sit on exactly the same point across all three continua. They’re a little left of middle on one, a little right of middle on another, and maybe extreme on a third. Or they’re close to an extreme on two, but dead-middle on the third. Remember that as you read through the profiles: They’re “averages” of tendencies I heard, not snapshots of the real men who related them to me.

The Unresolved Priest

The unresolved priest is a symbiotical fallenist conduit, which means he:

Symbioticist: Sees some of his work tasks (administration, pastoring, preaching) as reinforcing one another, but others as compartmentalized, un-integrateable

Fallenist: Believes it’s necessary but not desirable to reveal his own life experience and personality in preaching

Conduit: Isn’t sure how much agency he should seize in preaching relative to the Holy Spirit

So what does he look like in practice? It’s easiest to understand that if we work backward through the above.

Conduit practices. The unresolved priest’s preparation for preaching is minimal, almost entirely passive, and highly dependent on his schedule. He typically begins preparation for a Sunday homily on the Sunday before: After he delivers his last homily for the day, he looks at the readings for the upcoming Sunday just so they’re in his head. Thereafter, his contact with the readings can vary dramatically: On good days, he splits his Holy Hour between (1) intercessory and other prayer and (2) meditating on Sunday’s and possibly the next day’s daily Mass readings. On bad days, he doesn’t get to the readings at all, or he glances at them again for just a few minutes right before bed.

At all other times throughout the week, this priest simply holds the readings in the back of his mind, rarely reflecting on them consciously, which he calls “waiting on the Holy Spirit” (to give him a topic idea). In other words, he doesn’t actively engage with the readings at all during the week, and he has no external deadlines to hold him accountable for working with the texts until the Saturday Vigil Mass.

Why does he operate like this? Because the unresolved priest views the Holy Spirit’s inspiration as somewhat spontaneous, but wholly unpredictable, and he believes the priest is a conduit for that inspiration, a channel that must work to stay constantly open, which he does primarily by giving up his most valuable resource: time. He expects the Spirit’s inspiration to flow through him eventually, but it doesn’t perpetually fill him and he has no idea when the faucet will turn on. He must ask for it, beg for it even, and have faith that it’ll come in time for his first Mass — a faith he feels is sometimes tested. This is why he surrenders agency until the eleventh hour, to ensure he’s given the Holy Spirit all the time he possibly can. In his mind, his role as a preacher is primarily to wait, so he feels that his week of “sitting with [the readings] without thinking about [them]” (Fr. Louis,3 quoting Fr. Thomas Keating), despite being wholly unconscious, counts as preparation time.

Fallenist practices. On Saturday morning, just a few hours before his first delivery of the homily at the Vigil Mass, the unresolved priest’s active preparation finally begins. At this point, he’ll spend three or four hours consulting commentaries (he probably has one or two he favors and uses pretty regularly), either out of habit or because he still doesn’t have a topic idea.

If/when God does inspire him, he works with that inspiration only minimally, lest he influence the message too much. He’ll craft the basic idea just until it’s passably clear and engaging in his opinion. To do more would be to “get in the way” of God, to risk substituting his own words, agenda, and person for those of Christ. He calls this temptation “me-ology” (Fr. Cupertino), the tendency some preachers have to “preach themselves” rather than Christ. He resists that temptation by being very cautious when adding anything “entertaining” or “irrelevant” to the message as it was communicated to him by the Spirit — particularly stories about himself — because, while he understands that some such devices are necessary to hold people’s attention, he feels they’re an undesirable distraction from the pure Word of God he’d like to communicate. Were we not fallen beings, we could receive that Word unadulterated by things like personal stories, funny examples, and clever attention-getters. But since we are fallen, the fallenist preacher will accommodate our weakness, at least a little bit.

Once the unresolved priest has an idea, he’ll do one of two things to prepare for delivery:

- On a good week, he’ll make some unstructured bullets (possibly on a template he uses every Sunday to help him organize and simplify structure as well as prep faster), go over them, make minimal revisions once or maybe twice, then bring the bullets to Mass with him as notes. Only if he’s preaching on a very controversial topic, before the bishop, or possibly for a big holiday (and big audience) like Christmas or Easter, will he write out a full manuscript, or portions of one.

- On a bad week, he won’t write anything. He’ll simply come to Mass with the basic idea and possibly a simple structure in his head.

In any case, the unresolved priest won’t practice his homily. He won’t reflect on the most appropriate delivery style for this week’s particular message (but he probably has considered — once, a long time ago — whether standing at the ambo or walking about is most appropriate for his audience and which is most comfortable for him, so he’ll do whichever he always does). And unless something goes very wrong, he won’t revise his homily between Masses.

Symbioticist practices. After Mass, the unresolved priest won’t solicit feedback on his homily. Even when parishioners comment, “Great homily, Father,” as they shake his hand at the exit, he won’t seize that opportunity to dig deeper, either because he thinks it wouldn’t yield any useful information or because he worries about embarrassing the parishioner, who may not have listened at all and is just being polite. Only in a rare case of extreme uncertainty might the unresolved priest ask one person what they thought — probably a parish office worker or long-time parishioner. If he does hear more than “Great homily, Father” from somebody, he’ll take the feedback under consideration, but only if he feels it was fair and not the result of someone’s personal agenda.

Under no circumstances will the unresolved priest upload his homilies or any portion of them online. He feels this tears them from their essentially liturgical context, and so he receives no feedback in this way either.

Because the unresolved priest receives little to no feedback after preaching, he typically receives little to no feedback at all, because his choice to spend six days waiting passively for the Holy Spirit’s inspiration means he’s missed all opportunities to use parish activities like Bible study, youth group, or RCIA as preaching focus groups. But his symbioticist tendencies also play a role in that: It’s not as if he doesn’t participate in those activities — he does — he’s simply never thought to use them to get feedback on his preaching, or if he has, he feels it would be awkward or impractical to do so. The only time he may run his homily idea by anyone before he preaches is when he’s preaching on a very controversial topic.

In this way, the unresolved priest siloes his preaching work from other work tasks that could inform and facilitate it. But that siloing is a matter of degree: Most often, he can find some symbiotic relationship between his pastoral and preaching work, and between his preaching and personal life. But his administrative work he views as completely siloed. And even the overlap he finds between preaching, pastoring, and personal activities tends to be superficial: Usually, the only examples of symbiosis the unresolved priest can come up with are that he sometimes (but rarely) gets an idea for preaching from his pastoral or personal activities, and/or that he feels preaching forces him to live to a higher standard so as not to look like a hypocrite to his parishioners.

Similarly, just as the symbioticist priest is blind to some, but not all, potential synergies between workflows, he’s also closed to some, but not all, opportunities to learn from others. I found this tendency exists even in seminary: The unresolved priest most likely neither outright rejected nor unquestioningly assimilated everything he heard in homiletics class, but rather took some things on board and disregarded other things he didn’t like, disagreed with, or viewed as impractical. Since entering parish work, he won’t have sought out others’ homilies online or in person to use as examples or learning devices — and he is very leery of anyone using Protestant sermons for this purpose — but he does listen attentively and critically to others preach when he concelebrates.

The unresolved priest is just as much a fence-sitter when it comes to private reflection on his preaching practices. He feels there are things he could do to give preaching more time, but he also feels his current method is pretty much okay, so he doesn’t make changes. He may feel that any more time he could give to it would come at the expense of other things that are more important or that need more time; indeed, he likely prioritizes preaching below pastoral work, possibly even below administration. He nonetheless will say that preaching is a big responsibility that deserves his respect and diligence — a responsibility that’s sometimes extremely burdensome to him as he seeks to balance all his “separate” responsibilities.

The Fragmenting Priest

The fragmenting priest is an atomizing dualist lightning rod, which means he:

Atomist: Sees none of his work tasks as reinforcing one another; to him, they’re all completely separate

Dualist: Believes it’s both unnecessary and undesirable to reveal his own life experience and personality in preaching

Lightning rod: Believes he should seize no agency in preaching relative to the Holy Spirit

In practice, this priest is very simple.

Lightning rod practices. The fragmenting priest may or may not have a daily Holy Hour, but if he does he doesn’t use it to prepare preaching. In fact, he doesn’t undertake any preaching preparation prior to Mass. He doesn’t pray over the readings in advance, consult commentaries or other resources, nor prepare any kind of notes or manuscript. He doesn’t even know the readings until the lector proclaims them. He may begin to think about what he’ll preach as he hears the readings being proclaimed, or he may simply listen and then begin to formulate ideas once he starts walking to the ambo.

He feels this preparation process is not just sufficient but ideal, and he’ll staunchly defend it with arguments about preaching’s “short shelf-life” (i.e., people’s inability to remember preaching for very long; Fr. Nunc), its fundamentally liturgical purpose, the importance of other tasks, etc. Most basically, though, he’ll defend it by comparing his preaching relationship with the Holy Spirit to a lightning rod: The Spirit inspires him suddenly, at just the right moment, when the inspiration is needed. His job is to conduct that inspiration, not try to control or even influence it. Lightning rods are fond of quoting Luke 12:12 (but not Luke 12:11) to justify the claim that they are spontaneous channels of divinity and nothing more.

Dualist practices. As you can imagine, priests who believe that God wants them to be conductors, not shapers, of divine inspiration aren’t going to eagerly share of themselves in preaching. It’s not that they think priests aren’t present in the homily — every priest I spoke with acknowledged Fr. Nunc’s statement that “preaching is revelatory of the preacher” — just that they shouldn’t be. The dualist therefore tries to minimize this revelation as much as possible by not “packaging” the homily in eloquent or entertaining rhetorical devices. To him, these are just personal flourishes preachers unnecessarily add to the Holy Spirit’s already-perfect message.

Two favorite phrases of the dualist are “It’s not about me” and “I have to get out of the way.” In fact, these are favorite sayings of most priests, but if you listen closely and dig a bit into how they translate these maxims into practice, you’ll find dualists and non-dualists draw the “about me” and “out of the way” lines in very different places.

Atomist practices. Obviously, when you restrict all your preaching effort to the homiletic moment itself, you aren’t going to spend much time gathering feedback. In fact, the fragmenting priest is most likely to disdain preaching feedback as useless and never solicit it, either before or after Mass. Again, this is partly due to his orientations to the Holy Spirit, but also partly due to his total separation — usually unconscious — of all his other work and his personal life from his preaching work. He sees no relationship between pastoral care and preaching, or between his own experience of life and preaching. He doesn’t think about preaching in his spare time nor attempt to improve his preaching, because he believes it’s already exactly what God wants it to be. For the same reason, he brazenly disregards anything from his homiletics education that doesn’t suit him, maintains whatever content and delivery styles he’s comfortable with in every context, never seeks out examples of preaching, and rarely if ever listens while others preach.

Despite all this, the fragmenting priest may go either way when asked about the importance of preaching: On one hand, he may argue that it’s extremely important and actually a top priority for him, but that he’s gifted and this way of preaching has always worked for him and he’s even received positive feedback on his preaching in the past. (Yes, despite his disdain for feedback, this preacher will use it to defend his method.) On the other hand, he may argue that preaching is actually not important and has low priority for him for those reasons already mentioned above: preaching’s short shelf-life, its strictly liturgical role, etc. Either way, he doesn’t feel that preaching work itself is in any way a burden or heavy responsibility for him. Rather, he approaches it like a “professional courtesy” (Fr. Aaron Green) he does for parishioners.

I’ve heard a great deal of condemnation of the fragmenting priest, so before you judge him, I’d encourage you to recall Matthew 7:3–5, because while this priest may not be the most common among Sunday homilists, when it came to daily homilies, nearly every priest I interviewed came closer to this profile than any other.

The Integrative Priest

The integrative priest is a holistic incarnationalist reservoir, which means he:

Holist: Sees all of his work tasks as feeding into and reinforcing one another

Incarnationalist: Believes it’s both necessary and desirable to reveal his own life experience and personality in preaching

Reservoir: Believes he should seize lots of agency in preaching relative to the Holy Spirit

In practice, this priest is . . . awe-inspiring.

Reservoir practices. The integrative priest begins his preaching preparation months in advance, when he reviews upcoming readings to plan a big-picture strategy that will ensure he covers topics he feels his listeners need to hear. He writes these topics out on a schedule, which he looks at on a regular basis. Typically he always knows what’s coming up for the next two to three weeks, and he may begin (actively) brainstorming and outlining a homily at any point during this time. At the very latest, for a Sunday homily, he’ll begin working intensively the Sunday before delivery.

In the weeks leading up to delivery, his preparation is extensive and extremely varied. He likely has two daily Holy Hours: one for intercessory and contemplative prayer, another dedicated exclusively to meditating on the readings in preparation for preaching. To spark ideas for both Sunday and daily homilies, he may read the day’s Scripture passages in different languages (English, Latin, Greek, Spanish), and he regularly consults commentaries, study Bibles, Catholic monthlies, preaching books, preaching or other websites, and email newsletters or podcasts from famous preachers, theologians, Church historians, etc. He will even — with caution — use Protestant resources.

As he contemplates and studies the readings, he also actively works with them, all week long: He journals on them; podcasts on them; writes on them for a blog, website, printed worship aid for daily Mass, the parish bulletin, etc.; discusses them in Bible study, youth group, RCIA, etc.; and he meets weekly with other priests or an ecumenical group to discuss readings and homily ideas. Before each of these activities, he re-reads the readings, prays over them, thinks about them, and considers what to do with them for this particular activity. So does he set for himself clear external deadlines that effectively force him to prioritize preaching and that stave off procrastination.

When he’s ready to draw up a particular homily, he’ll use all of the resources he’s already created on the readings for other activities (journal entries, RCIA notes, etc.) to help him find something he feels will be relevant and powerful for his listeners at Mass. He may take a completely new angle on the readings, cobble together something from his various resources, or use just one particularly strong resource as the bulk of his message. Before settling on an idea, however, he’ll get feedback on it: from comments on his podcast and blog entries; from parishioners in Bible study, youth group, and RCIA; from administrative staff in office meetings and casual conversations; from other priests, deacons, visiting seminarians, friends; etc.

Clearly, this priest takes charge of his preaching. He’s an active agent who doesn’t expect the Holy Spirit to inspire on demand — because he doesn’t view himself as a conduit or lightning rod. He wholeheartedly welcomes the Holy Spirit’s inspiration, but he doesn’t wait passively for it because he sees himself as a reservoir of inspiration: The Holy Spirit is always and everywhere filling him with ideas and experiences and relationships from which to draw for preaching. His role as the preacher is to choose what, from this ever-available, ever-full reservoir of inspiration, he will pour out today.

Incarnationalist practices. In choosing what to draw out of his reservoir, the integrative priest acknowledges that he himself becomes a part of the preaching, incarnating the Living Water, the Word of God. This incarnation, he insists, is both necessary and desirable, because Catholic theology is fundamentally sacramental — that is, it’s all about God approaching man through the material, through Christ-made-flesh and Christ-in-His-saints. And if that’s how God and people and faith work, then the integrative priest figures it must also be how preaching works.

So, to flesh out the homily topic he’s chosen, the incarnationalist will add stories from his experience — about himself or others he’s met — use humor, let his personality show through, etc., in order to establish a clear, human connection between his listeners and his point about the divine. Then he’ll either extensively outline or completely write out the homily, practice it out loud, and revise and rewrite, sometimes substantially, multiple times. He’ll consider what style of delivery would be best for his particular context, audience, and message, but will most often come to the ambo or the front of the altar with either very minimal keyword notes or nothing at all.

After each delivery, he won’t hesitate to revise the homily or his delivery style if he feels it’s necessary. Often he knows a revision is necessary on his own. Other times he knows only from the feedback that he actively solicits from listeners.

Holist practices. The integrative priest has a robust feedback mechanism: He encourages all parishioners to give him feedback and, since most of them know him personally, not just from Mass, they often do give feedback — in person and by email, phone, and letter. When they give it, he follows up to ensure he understands their comments and to get any further information he needs to improve. To be certain he gets at least some feedback on every homily, he holds a regular after-Mass meeting of willing parishioners, with whom he sits and discusses the homily over coffee and snacks. He’s also devised ways to obtain long-term, big-picture feedback: Every Sunday, he uploads a recording of the homily to SoundCloud, iTunes, YouTube, or elsewhere, so he can follow which uploaded homilies get the most downloads, views, and comments. This, he believes, tells him what people are hungry for, and he adapts future homilies to feed them.

The integrative priest is able to give so much time to preaching work because he feels strongly that it’s intimately connected to all his other work — even to his personal life. That makes him a holist, one who feels that all aspects of his life and work flow into each other without separation or even distinction. Regardless of whether the immediate task before him is administrative, pastoral, or leisurely, he’s always and everywhere brainstorming, making mental notes, “collecting” stories and examples for use in preaching from his other work and his personal life. He may even record or write these down somewhere: The holist typically has a dictation app on his phone or a notebook in his pocket that he pulls out at (seemingly) random intervals.

This priest’s impressive openness extends to learning from others as well: He’s most likely incorporated his homiletics education into his parish work much more effectively than the fragmenting priest. He at least heard out that education and critically assessed — and re-assessed with every new parish assignment — what’s useful and applicable to him and his listeners. He even seeks out the preaching of others: He won’t ask to visit a parish or receive a recording just to hear another priest preach (this might make the other priest uncomfortable), but when he goes on vacation, he visits other parishes posing as a layman so that he can experience the homily as one. And he’ll seek out examples of preaching online, both audio and video, Catholic and Protestant, so that he can enjoy, critique, and learn from them.

Put simply, the integrative priest lives, eats, breathes, sleeps, and prays preaching. And despite all the time he already puts into it, he still wishes he could put in more. It’s invariably his top priority, a huge responsibility but not a burden, because he loves preaching more than any of his other tasks and feels strongly that he’s giving it all the time he can. He likely reasons that putting more time into focused preaching work would take time away from activities (e.g., interacting with the people, praying) that are necessary to get to the focused part. In other words, he considers himself to be balancing not preaching and non-preaching work, but two different types of preaching work: focused and preliminary, hands-on and preparatory, or direct and indirect. Because, to him, everything is preaching, he’s at peace with both his preaching process and his time allocations.

Conclusion

Looking at these profiles, and considering that the vast majority of Catholic priests are “unresolved,” we can see part of the answer to the question, “Why is preaching well so hard for Catholic priests?” It begins with conflict and confusion about how the Holy Spirit works in preaching, and ends with agentic guilt,4 homiletic stress, work exhaustion, and eventually burnout. Both fragmenting and integrative priests resolve these problems — but one of these resolutions we would surely not condone, possibly not even for daily preaching.

And after all, isn’t integrative preaching the truly Catholic way? What is the integrative priest but a living embodiment of the eminently Catholic “both/and”? The lightning rod all but obliterates the possibility of human cooperation with God in preaching, while the reservoir swims in a great homiletic river hand in hand with his God. The dualist constructs messages as if God’s taking human form has no relevance to homiletic method, whereas the incarnationalist infuses his preaching with the spirit of Immanuel. The atomizer divides up his work like a bureaucrat, but the holist knows that it’s all one big gift from God.

That’s why, when you meet an integrative priest, you’ll know him: The peace and joy — not to mention passion for preaching — that he emanates is unmistakable. I encourage you all to find such a man, learn from him, and become like him.

- See CARA, “Frequently Requested Church Statistics,” cara.georgetown.edu/faqs. ↩

- It’s unsurprising that men who voluntarily sacrificed 45–120 minutes out of their very busy schedules to talk about preaching with a total stranger should show so few fragmenting tendencies. As I explain in more detail in the book, priests who are willing to do this are probably not representative of the Catholic priesthood as a whole, which means there may be far more fragmenters out there than we would like. ↩

- All priest names cited are pseudonyms. ↩

- For more on this fascinating — and tragic — phenomenon, pick up a copy of the full study at the publisher’s website, bookshop.org, or Amazon. ↩

Priests should be aware of the culture parishioners are exposed to. One retired priest does reference the bad influence in our society and I like that. On Holy Family Sunday I was very disappointed this year. Family means children and the word children never was mentioned in the homily. And today there are lots of couples who do not want to have children when married. Priests need to speak about the joy and benefits of having children in a marriage.

J.E.

Powerful article. There is no question the integrative priest will bring the Word of God alive and become a formative of the People of God. Unfortunately, some form of the other two types is what we experience most frequently in Catholic homilies. As I read your article this thought kept running through my mind. The homilist can be integrative but if the sound system is bad, his beautiful homily will make little difference. This past Sunday I went to a Catholic Church, not my home parish, in which the sound system was bad. I could not understand the readings, the homily, and the words of the Eucharistic Prayer only because of my familiarity with them

Thank you, Tom. I’m glad you found it thought provoking!

I agree that technical and other “facilities” issues can also disrupt preaching, and the Mass in general. The Mass is itself a holistic experience, and everything about it is formative of our faith. On that subject, I’ve written another article for HPR about hymns in modern Catholic churches that you may find interesting as well. You can read that one here: https://www.hprweb.com/2015/07/whats-changed/