Exegetical Journeys in Biblical Greek: 90 Days of Guided Reading. By Benjamin L. Merkle. Reviewed by D. Malachi Walker. (skip to review)

He Gave Us So Much: A Tribute to Benedict XVI. By Robert Cardinal Sarah. Reviewed by Dr. Brandon Harvey. (skip to review)

God Is Ever New. By Pope Benedict XVI. Reviewed by Fr. Stephen Rocker. (skip to review)

Truth Plus Love: The Jesus Way to Influence. By Matt Brown. Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose. (skip to review)

Wisdom of the Heart: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful at the Center of Us All. By Peter Kreeft. Reviewed by Mike Schramm. (skip to review)

Exegetical Journeys in Biblical Greek – Benjamin L. Merkle

Merkle, Benjamin L. Exegetical Journeys in Biblical Greek: 90 Days of Guided Reading. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2023. 280 pages.

Reviewed by D. Malachi Walker.

In order to learn Greek, one needs resources to facilitate the process. One difficulty in the learning process is that there is an abundance of grammars, but the transition to reading “real” Greek, instead of the artificial sentences in grammars, can be a steep learning curve. While intermediate readers for Greek exist, advancing past the “grammar” stage of Greek can require a herculean effort. Benjamin Merkle’s book, Exegetical Journeys in Biblical Greek: 90 Days of Guided Reading has been written in order to decrease the steepness of this learning curve.

In order to learn Greek, one needs resources to facilitate the process. One difficulty in the learning process is that there is an abundance of grammars, but the transition to reading “real” Greek, instead of the artificial sentences in grammars, can be a steep learning curve. While intermediate readers for Greek exist, advancing past the “grammar” stage of Greek can require a herculean effort. Benjamin Merkle’s book, Exegetical Journeys in Biblical Greek: 90 Days of Guided Reading has been written in order to decrease the steepness of this learning curve.

Written as a sequel to Exegetical Gems from Biblical Greek, Merkle’s book contains 35 reading passages from many parts of the New Testament. Beginning with easy texts (e.g., John 1), this resource grades readings until one terminates in the difficult readings of 1 Peter, Jude, and Hebrews. The book is envisioned as helping someone right from the very beginning of their studies. A student in first semester Greek will be able to tackle the initial readings, and the book culminates in readings difficult enough that someone who just finished grammar classes will benefit.

Each reading is broken down as follows: first, a short snippet (1–2 sentences) is presented. Second and third, there is an empty chart for the reader to parse verbs and analyze nouns and adjectives. Fourth, there is a space to write down one’s translation. Fifth, there are helpful exegetical insights into the Greek text, thus showing the real benefit of learning Greek rather than being limited to reading with a translation. Finally, there is a “for the journey” section, both contextualizing the Greek passage and offering helpful ways to understand it.

There are two remarkably helpful things about Merkle’s book. First, there is a vocab section below each reading so that the reader will not have to flip through a dictionary, slowing down the time actually spent with the text. If more help is needed, there is also a vocabulary section at the back of the book. Second, there is an answer key to the parsing questions, as well as an English translation of the Greek text. This second point is most important. Having the answers provides immediate feedback to the student of Greek so that he or she will know what was correct and incorrect. While this is less pressing if this book is used in the classroom, and, therefore, will be corrected by the professor, it is vitally important for the student studying between semesters or by oneself after finishing Greek classes. There are few resources that provide such immediate feedback. Intermediate readings tend to parse difficult words, but Merkle has been quite fastidious in his desire to make the Greek text accessible to his reader, and thus provides an abundance of help in reading.

Merkle has intentionally written this book not to be used instead of a grammar book or reading the texts by themselves. The book is for those who need help transitioning from learning paradigms to reading the New Testament as it was written. To this extent, it is very helpful, and anyone who finds oneself in the beginner to early intermediate stage of Greek will find it very valuable.

The one objection one might bring to this book is that it jumps around between books. The book goes through snippets of John, Revelation, Matthew, Luke, Romans, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, Mark, James, 1 Peter, Jude, and Hebrews. It is, of course, helpful to be exposed to different books of the New Testament, so this is not a serious objection to the book. At the same time, sustained reading of the same text provides context, continuity, and a sense of accomplishment that one would not otherwise have. Of course, Merkle’s book is a learning resource, so the student should continue with reading a full text after getting the boost from this very helpful book. Merkle, the M.O. Owens Jr. Chair of New Testament Studies at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, has already written several books on New Testament Greek in order to provide resources for those who learn Greek, all of which are well worth their price. All in all, it is a great resource, and definitely worth a read.

D. Malachi Walker was born and raised in Nashville, TN. He received his Bachelor of Arts from the Pontifical College Josephinum in Columbus, OH and his Master of Arts from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Jerusalem, Israel. He is currently a PhD student at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana.

He Gave Us So Much – Robert Cardinal Sarah

Sarah, Robert. He Gave Us So Much: A Tribute to Benedict XVI. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2023. 229 pages.

Reviewed by Dr. Brandon Harvey.

While Benedict XVI died less than two years ago, it was hard for many of us to imagine that he had in fact reached the end of his earthly pilgrimage. This is partly because his time as pope ended more than a decade ago, but before his death, and also because his life and works continue to be explored along saints like Augustine, Aquinas, and Newman. Cardinal Robert Sarah in his work He Gave Us So Much: A Tribute to Benedict XVI attempts to offer a balanced look at a man whose depth we continue to explore and wonder at. This former Vatican prefect does not offer a chronological biography nor an anthology of papal works but sets out to offer a spiritual portrait.

While Benedict XVI died less than two years ago, it was hard for many of us to imagine that he had in fact reached the end of his earthly pilgrimage. This is partly because his time as pope ended more than a decade ago, but before his death, and also because his life and works continue to be explored along saints like Augustine, Aquinas, and Newman. Cardinal Robert Sarah in his work He Gave Us So Much: A Tribute to Benedict XVI attempts to offer a balanced look at a man whose depth we continue to explore and wonder at. This former Vatican prefect does not offer a chronological biography nor an anthology of papal works but sets out to offer a spiritual portrait.

After an introduction, the book is broken up into three sections. The first, a “Mystical Portrait of Benedict XVI,” begins with a prologue that situates the spiritual portrait as oriented to the reality that God is. The subsequent chapters of this section focus on explaining this orientation in his life, and the impact of this orientation on his relation with others. Regarding the latter, Cardinal Sarah offers specific examples of Benedict XVI’s fatherhood in his relationship with contemplatives, priests, and children. In this first section one will find stories of a pope that took God seriously, but did not take himself too seriously. This section is concluded with a strong sense that gentle Benedict’s identity and joy came from God, and that he practiced what he preached. “Faces of the Pontificate” organizes the second section of the book as a collection of works by Cardinal Robert Sarah spanning more than a decade that sketch out additional dimensions of the portrait. Some were written as prefaces to other works, some as articles, and others as addresses. This section ends with the inclusion of a preface aptly titled “Benedict the Great.” The closing half of He Gave Us So Much is a collection of works by Benedict XVI as a spiritual itinerary to accompany him in closeness to God.

One chapter that stands out among Cardinal Sarah’s works in the second section is his preface to a work on Benedict XVI and the petrine ministry by Christian Gouyaud that introduces to the reader intriguing insights into the nature of the papacy. For example, Matthew 16:17–19 is said to not be the most essential passage on the papacy. It is explained that these verses are the interpretation of the passage found in verse sixteen when Saint Peter offers a profession of faith. From here it is explored how the significance of the timing, the day of Yom Kippur, characterizes Saint Peter’s words here as a priestly action. Cardinal Sarah successfully demonstrates how this ideal of the Petrine Ministry was faithfully observed by Benedict XVI. He was not simply an intellectual pope and theologian; his central ministry was to confess faith in Christ. “The only reason for the pope’s place in the Church is so that, in his turn, he can let the Holy Spirit place upon his life the truth of God and of Revelation. We can gauge the strength with which Benedict XVI sought to correspond to this vocation” (74)!

From here the cardinal touches on his homilies, encyclicals, and his liturgical celebrations as continuations of Saint Peter’s profession of faith. It is interesting how Cardinal Sarah was able to briefly introduce the topic of ad orientem, the direction the priest faces at the altar, within this context. In this section he reminds us that the first pope did not start a Church but professed the faith. This point, manifested in all Benedict XVI’s works, demonstrates the pontiff’s own emphasis on the centrality of God. For confirmation beyond this tribute, one only needs to think of his desire to keep the Sacred Liturgy God-centered in Spirit of the Liturgy, or his magnificent Jesus of Nazareth trilogy. Looking at the other chapters of this section, the reader will find some interesting and occasionally new insights. The one challenge in reading these collected works from the cardinal is that they were not written with the intention of existing together or having an organic relationship between them. This means that the themes or details of one might be repeated in others.

The final section, “A Spiritual Itinerary with Benedict XVI,” provides twelve samples of his works as pontiff and some prior to his ascent to the Chair of Saint Peter. Overall, they connect well to themes and insights explored in the previous sections. If one were to doubt the cardinal’s presentation of the spiritual portrait of Benedict, one only needs to then read this final section. Whether it is Benedict’s view of the priesthood or religious life, the centrality of God, his interactions with children, the importance of the liturgy, or recounting horrors from the Nazi regime, one finds in these speeches and written works a continuity with the rest of the book. It rightly produces the effect for the reader that Benedict XVI was the authentic kind of man that displayed a unity between his beliefs, words, and actions.

One also finds in reading this section that to be initiated or re-initiated into the thought of Benedict XVI is not to enter into a man’s preferences or theories but rather a faith that he believed himself to be steward of. Each of these chapters can then serve as a spiritual process for the reader that begins with the importance of God, the kind of God that we believe in, and how to wrestle with the existence of suffering in a world at the same time. In his funeral homily for Monsignor Luigi Giussani, we are then reminded of a theme found consistently throughout his works. “Christianity is not an intellectual system, a collection of dogmas or moralism. Christianity is instead an encounter, a love story; it is an event” (134). To unpack this, a chapter then explores beauty. This then wonderfully transitions into chapters that explore the nature of the Church and her sacramental liturgies; in it some of the words about committees, activism, and problematic imitations of democracy within the Church prove to not only be timeless insights but potent wisdom as the Church in our time ponders the meaning of synodality. After exploring the role of certain vocations, one ends with a powerful reflection that more fully applies previous principles of the centrality of God and the danger of a societal eclipse of God in considerations about the human person. The chapters read like a retreat into the heart of Christianity.

I was thankful to reread Benedict’s “A Heart Pierced by Beauty” speech from 2002 and for my first time reading “The Grandeur of Man Is His Resemblance to God” speech from 1996 that reflects on the imago Dei. Yet, I am also thankful that Cardinal Robert Sarah gifted the Church this tribute for the man that gifted us so much. Many of us are convinced that Benedict XVI was one of the greatest figures and theologians of the Church’s history with a comparison to those the Church honors as Doctors of the Church. It would be a great deprivation for all of us that have been touched by his life and ministry to not pass it onto future generations in order to help them enter more fully into communion with God. He Gave Us So Much is not simply a tribute but allows future generations to connect with the pontiff as if they were alive to witness such a spiritual master.

Brandon Harvey, D.A., teaches for Catholic International University where he also serves as assistant director of undergraduate programs.

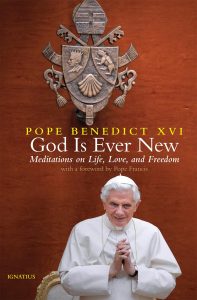

God Is Ever New – Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI. God Is Ever New. Edited by Luca Caruso. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2024. 161 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Stephen Rocker.

This book is a collection of short excerpts, what Pope Francis in his foreword calls “a spiritual synthesis,” from Pope Benedict’s papal homilies, addresses, and encyclicals. They’re grouped by such themes as “faith,” “love,” “prayer,” “holiness,” “truth and freedom.”

In speaking to children who had made their first Communion, the pope said, “We do not see our soul, and yet it exists and we see its effects . . . it is precisely the invisible things that are the most profound, the most important.” And in the same meeting, but quoted in another part of the book, he said, “The people who do not go to church do not know that it is precisely Jesus they are missing. But they feel that something is missing in their lives.”

Pope Benedict spoke often of faith. “Saying ‘I believe in God’ means founding my life on him, letting his Word guide it every day, in practical decisions, without fear of losing some part of myself.” Faith needs to be strong in the counter currents of society because

it is far from easy to be faithful to Christian marriage, to practice mercy in daily life, to make room for prayer and inner silence; it is far from easy to oppose publicly the decisions that many take for granted, such as abortion in the case of unwanted pregnancy, euthanasia in the case of serious illness, and embryo selection in order to prevent hereditary diseases. . . . The temptation to set faith aside is always present, and conversion becomes a response to God that must be strengthened several times in life.

In fact, he noted we must give priority to making God present in the world because in large stretches of the world “the faith is in danger of dying out like a flame that no longer has fuel.”

The Christian idea of freedom in contrast with the secular world’s is a frequent theme in Joseph Ratzinger’s writings. As that contrast bears upon the family, Pope Benedict noted,

Freedom without commitment to the truth is made into an absolute, and individual well-being through the consumption of material goods and transient experiences is cultivated as an ideal, obscuring the quality of interpersonal relations and deeper human values; love is reduced to sentimental emotion and to the gratification of instinctive impulses, without a commitment to build lasting bonds of reciprocal belonging and without openness to life.

He spoke of maturing in prayer as a “stairway.”

We must learn more and more what it is that we can pray for and what we cannot pray for because it is an expression of our selfishness. I cannot pray for things that are harmful for others; I cannot pray for things that help my egoism, my pride. Thus prayer, in God’s eyes, becomes a process of purification of our thoughts, of our desires.

Quoted in another part of the book, he said, “Faith and prayer do not solve problems but rather enable us to face them with fresh enlightenment and strength, in a way that is worthy of the human being.”

As a small book, God Is Ever New is easy to hold and has an attractive feel, but how much nourishment and satisfaction the reader derives from these morsels may vary. For this reader the short quotations were not connected and developed enough to be satisfactory. For example, in a general audience Pope Benedict stated that when God disappears, human beings fall into slavery as the rise of nihilism and totalitarian regimes demonstrate. Such a statement might be appropriate to a general audience but the “why” of the cause and effect connection between God’s disappearance in human life and the rise of nihilism and totalitarianism is wanting. There are probably people who might like to give or receive this book as a gift, but generally the reader of Ratzinger/Benedict would be more enriched by selecting for perusal from the headings or table of contents of his books, interviews, lectures, and encyclicals.

Rev. Stephen Rocker is a priest of the Diocese of Ogdensburg (New York).

Truth Plus Love – Matt Brown

Brown, Matt. Truth Plus Love: The Jesus Way to Influence. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2019. 208 pages.

Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose.

Countless surveys point to a crisis in Christianity. Disaffiliation across denominations has reached historic numbers. Voices critical of Christian theology and morality speed around the world thanks to the ubiquity of social media platforms. Even the most intellectually persuasive apologetical arguments fall, oftentimes, not on merely deaf ears and blind eyes, but on distracted audiences. How can Christians present to such a world our message of renewed life in Christ?

Countless surveys point to a crisis in Christianity. Disaffiliation across denominations has reached historic numbers. Voices critical of Christian theology and morality speed around the world thanks to the ubiquity of social media platforms. Even the most intellectually persuasive apologetical arguments fall, oftentimes, not on merely deaf ears and blind eyes, but on distracted audiences. How can Christians present to such a world our message of renewed life in Christ?

The answer, author and evangelist Matt Brown proposes, lies not in merely preaching the truths of the Gospel (which can lead to “noise”), nor simply loving in Christ (which can lead to error), but in a wedding of Truth and Love (28–30). Truth and Love together allows the faith-filled Christian to have a greater influence on the world. This influence, whether through our in-person conversations or through our social media posts, will transform the world. We maintain this balance of Truth and Love, Brown posits, by tapping into a spiritual source common to all Christians: the Fruits of the Holy Spirit, as laid out by St. Paul in Galatians 5:22–23. How Christians can take these Fruits and build up their influence in our modern world is the thesis of Brown’s book. Most importantly, Brown emphasizes that the purpose of our influence is not for us or to be “influential for the sake of being influential,” but “to be influential for Jesus! This is Jesus’s way of influence” (193).

The book’s structure follows the Fruits as listed in Galatians 5. Each chapter presents a meditation on the Fruit, rooted deeply in the Scriptures, that draws connections between the Word of God and our own lives. Brown draws on his own life and family’s experiences, as well as notable Christians (Billy Graham most especially, but also D. L. Moody, Henrietta Mears, Francis Schaeffer, Mother Teresa, and others) to exemplify how the Holy Spirit moves in the lives of those who use the Fruits of the Spirit. By far the most frequently quoted author is St. Paul, whose epistles form the bulk of the Scripture citations. At the end of each chapter Brown provides concrete ways to grow in that chapter’s Fruit. These encouragements are sometimes very specific, other times purposely broad, to accommodate a range of readers’ life situations.

Brown wraps up the book by emphasizing again that uniting Truth and Love gives the Christian an “uncommon influence.” That influence comes across in a variety of ways, from transforming our places of work to continually serving others. All of this has, as its goal, loving as God loves, whether publicly or privately, noticed by others or done anonymously. “That,” Brown concludes, “is how we change our world” (203)

From a specifically Catholic perspective, Truth Plus Love has several positive points. One cannot but notice the evangelical passion Brown brings to his ministry. Brown’s training and experience applying the Sacred Page to his pastoral work comes across beautifully. Truth Plus Love amounts to an extended example of what the Catholic Tradition calls the moral sense of Scripture. The concrete ways to live the fruits of the Spirit, which conclude each chapter, are an example of this. The book as a whole is a good reminder for anyone involved in ministry to balance the truths of the Faith with the Charity found in Christ, living out the fruits of the Spirit not only in our personal mission fields, but more importantly in our own lives. Brown would agree with the famous adage of Pope St. Paul VI: “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.”

That said, Catholics might note that while Brown does reference the heroic witness and teachings of several notable modern Christians, he does not mention any Christian saint, Catholic or otherwise, from the Apostolic Age through the eighteenth century, save St. Augustine of Hippo. Indeed, Brown would have found strong support for Truth Plus Love in the writings of other Church Fathers, in the Comedia of Dante, in the lived witness of St. Francis of Assisi, in the papacy of Pope St. John Paul II, and Benedict XVI, whose encyclical Caritas in veritate (“Charity in Truth”) applies the same principles of Brown’s work to issues concerning human progress. Similarly, Brown’s spiritual advice and encouragement to Christians facing moral struggles could be bolstered by a Catholic sacramental vision. Brown rightly points out that God moves in our lives, and offers His grace to us, but unfortunately, as a Protestant, cannot make reference to the sacramental graces available through Confession and the reception of Jesus Christ Himself in the Eucharist. One wonders, if Brown’s profound scriptural interpretations were infused with these uniquely Catholic supplements, what work of spiritual depth might be produced.

These points aside, there is much gold in this work. Catholic pastors of souls and catechists who read this book could easily highlight its benefits, and incorporate them into discussions of morality and spirituality. The bottom line, as indicated throughout the book, is that Christ is Truth and Love, that He calls us to abide in His love (John 15:10), and he has given us nourishment to witness that love in the fruits of the Holy Spirit. We need only ask Him.

Matthew B. Rose (BA, MA, Christendom College) teaches Theology at Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, VA; he writes for a variety of online resources, especially his blog, Quidquid Est, Est.

Wisdom of the Heart – Peter Kreeft

Kreeft, Peter. Wisdom of the Heart: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful at the Center of Us All. Gastonia, NC: TAN Books, 2020. 388 pages.

Reviewed by Mike Schramm.

Likely the most appealing thing about the writing of Dr. Peter Kreeft is that it is a unique mix of the old and new styles. He is very scholastic and medieval, and believe me when I use those terms in the very best sense, in his clarity and hierarchical distinction of ideas, but he is also very phenomenological and personable in his focus and style.

Likely the most appealing thing about the writing of Dr. Peter Kreeft is that it is a unique mix of the old and new styles. He is very scholastic and medieval, and believe me when I use those terms in the very best sense, in his clarity and hierarchical distinction of ideas, but he is also very phenomenological and personable in his focus and style.

This combination is on full display in his robust yet readable Wisdom of the Heart: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful at the Center of Us All. The title evokes thoughts of another Catholic philosopher, Dietrich von Hildebrand, who wrote a book of similar title and focus, The Heart: An Analysis of Human and Divine Affectivity. Kreeft mentions him early in his own book because I suspect he is writing a sort of updated version of von Hildebrand’s here, but for a popular-level, modern audience.

Kreeft has always been able to speak to this audience, surely because of his day-to-day interactions with philosophy undergrads, especially those students who are only taking his class as a requirement to graduate. While many of Kreeft’s readers may qualify as “the choir,” to whom he can easily preach, he hones his skill as a persuasive proposer of questions and considerations with those whose assumptions he doesn’t share. Speaking to the hearts of this audience, or providing guidance for those who do, is an ambitious prospect.

This is a very ambitious book in that it seeks not only to address the classic transcendentals of goodness, truth, and beauty in their philosophical origins, but also to connect them to the unique revelation of Christianity, all-the-while from the phenomenological focus of the individual. If phenomenology could be described, in an admittedly oversimplified way, as the bridge between the objective and the subjective, that is where this book seeks to live. In every topic that Kreeft explains, he always tries to do it less as something “out there,” and more as something “in here,” one’s heart. Though with his Thomistic philosophical subtlety, Kreeft also seeks to show that the “heart” cannot be reduced to mere emotion, while at the same time showing the necessary and powerful place emotion holds in thought, decision and action.

One of the things that makes the “heart” such an engaging topic is the ubiquity it holds in human culture. Kreeft gets to put his widely read literacy on full display by integrating his specialty in philosophy with his knowledge of scripture, psychology, literature and modern media. Because he dips his toe in all these areas, this book proves useful for one who wants to connect with people, and connect them to the Faith, from a variety of different angles. I imagine a priest or deacon could flip through the easily divided and organized chapters and find useful fodder for a year’s worth of homilies that a congregation could see as part of their experience.

As an initiated fan familiar with Kreeft’s style, I enjoyed what have become expected turns of phrase and references. However, I wouldn’t consider this book as my first recommendation if I were trying to hook someone else. There are points that one could describe as meandering and sometimes the divergence could be distracting. Again, I say this as someone who has always found Kreeft a charming, illuminating, and entertaining writer. Could the book afford to trim some of its fat? Maybe, but the sections imitate the feel of a college class lecture. One wouldn’t want it to be tightly scripted but feel more extemporaneous. One imagines this book was heavily influenced by lectures Kreeft has given many times in hopes of persuading as well as informing his students. Talking with real people about these real, sometimes sensitive, topics of the heart can be messy.

One of the finer, though perhaps to some less interesting, details that I find worth including is the way it is organized. As a teacher, I will sometimes read a book with a “how would I teach this concept” approach. Kreeft has broken down the topics very thoughtfully, so that a reader could conceivably make a focus on a general topic of emphasis like “The Good” or “The Beautiful,” or a specific topic like “Five arguments from the heart for God” or “Joy.” While I’m not saying one should read this book piecemeal like a reference manual, one could revisit sections on their own without feeling like one needs to reread the whole book for context.

If the Western philosophical tradition really is a series of footnotes to Plato, then perhaps the Christian psychological tradition is a series of footnotes to St. Augustine’s Confessions (this is actually kind of the premise to another Kreeft book). Kreeft has not been scared to stand on the shoulders of giants like Augustine, Aquinas, Pascal, Kierkegaard, and now Von Hildebrand. Fortunately for us, he is not only courageous enough to stand on those shoulders, but generous enough to reach down to pull us up. Wisdom of the Heart is yet another opportunity for us to grab Kreeft’s hand and begin our climb.

Mike Schramm teaches theology and philosophy at the high school and college level in La Crosse, Wisconsin. He earned his MA in theology from St. Joseph’s College in Maine and an MA in philosophy from Holy Apostles College. He is the managing editor of the Voyage Compass, an imprint of Voyage Comics and Publishing, and co-hosts the Voyage Podcast with Jacob Klatte.

Recent Comments