Rethinking Cooperation with Evil: A Virtue-Based Approach. By Fr. Ryan Connors. Reviewed by Fr. Joseph Briody. (skip to review)

John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer. By Thomas J. Shelley. Reviewed by Fr. Ryan Connors. (skip to review)

The Seeker’s Catechism: The Basics of Catholicism. By Michael Pennock. Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose. (skip to review)

Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins: Twelve Ancient Cities and How They Were Evangelized. By Mike Aquilina. Reviewed by Ted Hirt. (skip to review)

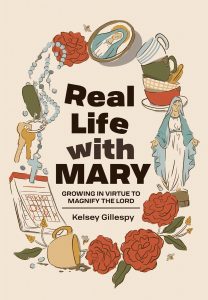

Real Life with Mary: Growing in Virtue to Magnify the Lord. By Kelsey Gillespy. Reviewed by S.E. Greydanus. (skip to review)

Rethinking Cooperation with Evil – Fr. Ryan Connors

Connors, Fr. Ryan. Rethinking Cooperation with Evil: A Virtue-Based Approach. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2023. 313 pages.

Reviewed by Rev. Joseph Briody.

For the inspired psalmist, there was no question of cooperation with a thief (Psalm 50:18). However, situations are not always simple and sometimes give rise to perplexity on the part of the inquirer. The thoroughly researched Rethinking Cooperation with Evil responds to such perplexity. Rethinking is for the seeker who wants to do the truth in love (cf. Eph 4:15). It proposes anew the depth, beauty, and value of the virtuous life. Rethinking immerses the reader in the truth and nobility of creation. Made in God’s image and likeness, the human person counts. Human action is meaningful and has an inner direction. It participates in the purposefulness of the Creator who draws us to himself and so to blessedness.

For the inspired psalmist, there was no question of cooperation with a thief (Psalm 50:18). However, situations are not always simple and sometimes give rise to perplexity on the part of the inquirer. The thoroughly researched Rethinking Cooperation with Evil responds to such perplexity. Rethinking is for the seeker who wants to do the truth in love (cf. Eph 4:15). It proposes anew the depth, beauty, and value of the virtuous life. Rethinking immerses the reader in the truth and nobility of creation. Made in God’s image and likeness, the human person counts. Human action is meaningful and has an inner direction. It participates in the purposefulness of the Creator who draws us to himself and so to blessedness.

Much unnecessary perplexity can be avoided by noticing what an action is about and practicing, that is, living the virtues. Fr. Connors highlights character formation and how the practice of virtue bears the fruit of ease and timeliness in making good decisions. Focus on what the human act is about — on its teleology — places us within God’s purposes. Virtuous living guides us in the right direction, and, through the lens of virtue ethics, actions are reinvested with their splendor and weight that help us recognize our dignity and responsibility before God.

In his erudite, generous, and balanced work, Fr. Connors acknowledges the clear counsel of authors of the casuistic school. He also acknowledges the limitations of some strands of moral thought. Casuist authors diverged in their interpretations of formal and material cooperation and what it means to share the evil will or intention of another. Fr. Connors points out that the calculation of consequences and proximity to the sin in question is absent from Saint Thomas Aquinas, who prefers to highlight the natural teleology of acts.

Much moral discussion followed after Saint Alphonsus Liguori focused on proximity to the evil in order to determine the morality of the cooperative act. Rethinking praises Saint Alphonsus for a “humanization of moral theology,” a move away from rigorism. Connors suggests, however, that focus on the act itself and its natural teleology reduces the need for so many “distinctions between various types of cooperation.” (p. 51) In the manual tradition, people were still left “to consider whether they possessed a truly grave or proportionate reason to justify their cooperation.” Perplexity perdured.

Fr. Connors draws together interesting examples from the work of Thomas Slater S.J. (d. 1928). Pub owners shouldn’t sell intoxicating beverages to the intoxicated. Other authors permitted this if a quarrel ensued. Book sellers should not sell immoral books. Those who organize social gatherings “may permit dancing.” However, while “those who sin frequently at dances should refrain from attending,” those who “only sin occasionally may attend when they take precautions.” Much here for the consideration of the perplexed socialite!

From his second chapter, Fr. Connors gets into his stride and the substance of his excellent work emerges with clarity and refinement. The big question surfaces: what kind of act is the act of (possible) cooperation in evil? It’s not so much about the distance from the act of the other person (formal, material, remote or proximate cooperation) as it is about the nature of the act of the cooperator. Is this an act that “conforms to the truth about the good of the human person”? A nurse’s handing of instruments to a surgeon could be a good or indifferent act. However, the handing of instruments to an abortionist “fails to conform to the truth about the good of the human person” and “no inconvenience can justify such a bad act.” It is, in fact, “immoral cooperation in the taking of innocent human life.” (65) The problem with some casuist thinking is that the obligation to conform to the truth sometimes seems to slip when faced with inconvenience. Surer guidance is found in “a virtue-based approach to moral cooperation, with reference to analyzing the act of the cooperator by means of the act’s natural teleology.” (65) In a virtue-based approach, the focus shifts from the imposition of external law to living from within what is true, good, and noble.

It is difficult not to enjoy Connors’s summary of the Jone-Adelman manual which covered issues of cooperation in the early twentieth century. Servants could accompany their employers to Protestant services but must refrain from singing or responding. “The ringing of bells in non-Catholic churches or advertisements in newspapers may be permitted as these acts only make known the times of the services and do not encourage attendance.” More practical, perhaps, is “One may contribute money to non-Catholic schools or orphanages since their principal purpose is charity and not proselytization.” (82) Jone-Adelman allowed “druggists to sell contraceptives in order to retain their jobs. A druggist may not, however, direct customers to purchase contraceptives.” (83) As Connors observes, with this method, “the perplexed conscience is often left with as many questions as answers.” (84)

The main question concerns what the cooperator (in evil) is doing. (90) The situation of the innocent person forced at gunpoint to assist in a robbery could be classified as “justified material cooperation with evil.” (91) But, Connors asks, is this really the best way to describe what’s happening? Fr. Connors opines that the one held at gunpoint is not doing the stealing. Rather, he is preserving his life and so is asserting that a human life is more valuable than material goods. No one would seriously argue that one ought to die rather than allow the goods to be taken. (91) It’s not that the person held at gunpoint is justified in acting badly. Rather, he is “acting prudently with material goods for self-preservation.”

Some moralists permitted participation in certain acts for a serious reason. However, this can become very subjective. No matter what the circumstances, “certain objects are not conformable with the truth about human flourishing.” (96) Critiquing Bernhard Häring’s The Law of Christ, Connors observes that “readers will find something wrong in his [Häring’s] method. Why would a Christian moral theologian hesitate to instruct a nurse handing instruments for an abortion to summon the courage to object and provide positive assistance to the unborn child instead of the abortionist?” It is a duty and a right to refuse to take part in injustice. (Evangelium Vitae, 74; Connors, 99)

The unhelpfulness of getting mired in calculations surrounding formal, material, remote, and proximate cooperation, etc., is illustrated well in another example when “Häring claims that a solider who follows orders to kill an innocent person is ‘guilty of formal cooperation in the sin of murder.’ It would strike most authors as more accurate to say that the soldier has committed the sin of murder, albeit in unique circumstances.” (100) Connors’s approach is simpler, more commonsensical, and rings true.

Casuistry did not provide the consensus imagined and perplexity often remained. A virtue-based approach views moral laws as springing “from the nature of human action itself” and leading to happiness with God. (118–119) Freedom is for excellence and human flourishing and “finds its sources in the natural inclinations of man to truth and goodness.” (121) Neither duress, coercion, nor good intention can “turn a bad act into a good one” (144), though such factors may reduce guilt. (128) Some acts, by their very nature, can never be chosen in truth and love. While one may be hindered from doing good — for instance, by a government policy — a person “can never be hindered from not doing certain actions, especially if he is prepared to die rather than to do evil.” (Veritatis Splendor, 52; Connors, 141, my emphasis) While “the state may inhibit good activities, it can never force Christians to do immoral things.” (197)

Here enters the idea of martyrdom, the crown of virtue. Some actions cannot be chosen without sin. This realization can change a life and inspire a person who, if not called to die for God who is Truth and Love, will strive to live for him. A person has only one life and he or she desires (presumably) to live that life with meaning and purpose.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of Rethinking is the vital reminder that human acts count: what we do contributes to what we become, to what we make of ourselves before God. Acting virtuously shapes a purposeful life in the direction of fulfillment and perfection. The importance of formation in virtue emerges clearly. No set of guidelines or external laws can replace this. This is the way of Christ who did “not hesitate to take the part that virtue and the highest virtue suggested to him” (Pope Francis, Dilexit nos, 128).

Rev. Joseph Briody, S.T.D., is Professor of Sacred Scripture and Coordinator of Spiritual Formation at Saint John’s Seminary in Massachusetts.

John Tracy Ellis – Thomas J. Shelley

Shelley, Thomas J. John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America, 2023. 238 + xiv pages.

Reviewed by Rev. Ryan Connors.

Long recognized as the dean of American Catholic historians, Monsignor John Tracy Ellis (1905–1992) merits a book-length biography. With a curriculum vitae numbering some 395 publications and decades of teaching and doctoral direction, his contribution to twentieth-century Catholic life has been the subject of wide admiration.

Long recognized as the dean of American Catholic historians, Monsignor John Tracy Ellis (1905–1992) merits a book-length biography. With a curriculum vitae numbering some 395 publications and decades of teaching and doctoral direction, his contribution to twentieth-century Catholic life has been the subject of wide admiration.

A student and friend of Monsignor Ellis, Thomas J. Shelley (1937–2022) has received acclaim for his scholarly histories of St. Joseph’s Seminary, Dunwoodie, NY, and of Fordham University in the Bronx. With this text, readers learn that in the discipline of Church history, Ellis occupies a middle position between the historical methodology which both preceded and followed him. A student of Monsignor Peter Guilday (1884–1947) at the Catholic University of America, Ellis is credited with transforming the study of Church history in the United States from a discipline of apologetics to a historical science in its own right. Ellis took his cue from Pope Leo XIII who, in opening the Vatican archives to historical research, explained that the first duty of the historian is never to lie and the second is to tell the truth.

Many recall a time when the study of Church history remained under close watch by ecclesiastical superiors. The pre-conciliar period witnessed debates about the extent to which Church archives should be open to lay historians lest they be scandalized by what they learned. For his part, Ellis desired that the study of Church history would earn the respect of secular historians. At the same time, Ellis focused his scholarly work on the contributions of bishops and, for lack of a better term, on the institutional Church. After Ellis had completed the bulk of his scholarly contribution, the bottom-up history of Jay P. Dolan (The American Catholic Experience: A History from Colonial Times to the Present, New York: Random House, 1987) would part ways with the methodology and emphases of Ellis and his predecessors.

The text under review unfolds in twenty short chapters, some properly biographical and others more thematic in nature. Readers benefit from the many citations from Ellis’s extensive personal correspondence. The text moves swiftly from his rural upbringing in Seneca, Illinois to his studies in Washington and later priestly formation with the Sulpicians in the same city. In addition to his teaching at The Catholic University of America and at the University of San Francisco and longtime service as editor of the Catholic Historical Review, Ellis served several times as scholar-in-residence at the North American College in Rome where he was appreciated for his balance and wide learning.

Today Monsignor Ellis is most remembered for his The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons: Archbishop of Baltimore, 1834-1921, 2 vols. (Milwaukee, Bruce, 1952). Harvard University historian Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. had voted to award Ellis the Pulitzer Prize for this important book. Schlesinger, remembered for his comment to Ellis that anti-Catholicism remains the deepest bias in the history of the American people, remarked: “It was entirely too much to hope that a biography written by a Catholic priest on a Catholic cardinal would ever win the prize” (69).

A major theme of Ellis’s written work was his contention that American Catholics had offered an inadequate contribution to intellectual culture in the United States and beyond. His 1955 essay “American Catholics and the Intellectual Life” remains the touchstone for this debate on the contributions of Catholics to theology and higher education. Shelley recalls in several places Ellis’s view that there were too many Catholic colleges emerging at mid-century and consolidation would prove necessary.

Monsignor Shelley labored on this book at the end of his long life. To this reviewer’s mind, the text would have benefited from the removal of some sweeping editorial comments, especially regarding the publication of Humanae vitae and his view of the process of episcopal appointments. When the text asserts that Ellis “found the liberals of his day more to his liking than the conservatives” the footnote provided is only “Ellis to the author” (178).

Shelley more than once quotes approvingly noted Church historian Jay Dolan’s assertion that Ellis “used history as an instrument to promote changes he believed necessary to American Catholicism” (88). Some readers may wonder whether the use of history for this purpose is any more noble than the apologetic history which Shelley asserts Ellis eschewed in order to respect historical science as its own discipline.

The book’s most touching vignettes are those regarding Ellis’s own spiritual life. Readers learn of his Sulpician-informed spiritual discipline to which he remained devoted throughout his life. Shelley explains that Ellis was happy to return to CUA after years spent in San Francisco and Rome and was “never happier and more pleasantly situated than during the last decade . . . with the chapel one floor down where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved” (167). Monsignor Ellis as priest and historian offered a singular contribution to American Catholic life. This volume will be welcomed by his many students and admirers.

Rev. Ryan Connors is a priest of the Diocese of Providence and Rector of the Seminary of Our Lady of Providence (Rhode Island). He is the author of Rethinking Cooperation with Evil: A Virtue-Based Approach (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2024) and co-author with J. Brian Benestad of Church, State, and Society: An Introduction to Catholic Social Doctrine, Second Edition (Washington, DC, The Catholic University of America Press, forthcoming).

The Seeker’s Catechism – Michael Pennock

Pennock, Michael. The Seeker’s Catechism: The Basics of Catholicism, Updated Edition. Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2023. 180 pages.

Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose.

Where does one start when investigating the Catholic Faith? I speak not of those first steps toward conversion from disbelief, wherein one’s faith obstacles are extensive and multifaceted, but rather, how one goes about investigating the specifics of the Catholic Church. An eager evangelist might point the seeker to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, that beautiful “sure norm for teaching the faith,” as Pope St. John Paul II described it; at the same time, the Catechism is a daunting work, perhaps even overwhelming to a new catechumen. Those seeking to know more about the Faith, without becoming overwhelmed, find in shorter guides a helpful step toward the fullness of the Church’s teachings.

Where does one start when investigating the Catholic Faith? I speak not of those first steps toward conversion from disbelief, wherein one’s faith obstacles are extensive and multifaceted, but rather, how one goes about investigating the specifics of the Catholic Church. An eager evangelist might point the seeker to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, that beautiful “sure norm for teaching the faith,” as Pope St. John Paul II described it; at the same time, the Catechism is a daunting work, perhaps even overwhelming to a new catechumen. Those seeking to know more about the Faith, without becoming overwhelmed, find in shorter guides a helpful step toward the fullness of the Church’s teachings.

It is to serve just such a purpose that Michael Pennock, legendary theology teacher and author of several high school theology textbooks, crafted the first edition of The Seeker’s Catechism, originally published in 1994, when the Catechism of the Catholic Church was new. Now, thirty years later, Ave Maria Press has blessedly re-released the Updated Edition of this little book, simple in size, deep in content. This book is not a work of apologetics, with objections to Catholicism proposed and refuted; rather, it is true catechesis, for as Pennock notes in the Introduction, “This book is especially for those who want to know more about how Catholics journey to God the Father” (p. vii). Indeed, a running theme throughout this catechism’s nearly 200 questions is how one seeks out God and, ultimately, encounters Him most fully through the Catholic Church.

To aid seekers in their journey to the Father, Pennock generally proceeds along the ancient catechetical path through the Creed, Sacraments, Morality, and Prayer. The chapters follow a simple structure, beginning with a brief introduction to their topic, followed by a series of questions and accompanying answers, and concluding with a quote from a saint and a reflection question. The first eight chapters trace out the essentials of our Faith, namely the nature of God, Christ, and the Church. From this brief survey of theology, Pennock moves into morality, devoting three chapters to how the Christian lives within human society (he leaves questions concerning human sexuality to the chapter devoted to Christian Marriage). Pennock then discusses the Christian’s life in Grace through the Sacraments, concluding the book with chapters devoted to prayer, the four last things, the Communion of Saints & Mary, and the Church’s relationship with other religions. After a conclusion, Pennock includes some traditional Catholic prayers and a brief section on next steps for those interested in becoming Catholic.

This work lays out the essentials of the Catholic Faith using uncomplicated vocabulary. It does not present a personal narrative for Pennock’s life, nor does it present an apology for scandals in the Church’s history. Instead, the simplicity of the question and answer format allows the catechetical discussion to take center stage. Each question and the accompanying answer is succinct. Every question in this Updated Edition includes several references to paragraphs from the Catechism of the Catholic Church, so that the reader can dig deeper into the sources for the answers. The saintly quotes and brief reflections at the end of each chapter, another addition in the Updated Edition, encourage the reader to incorporate the Church’s teaching into their own “journey to God,” reflective of Pennock’s background as a classroom teacher. The questions Pennock poses for reflection invite the reader to deeper thinking, and one senses he drew these reflections from his own ministry in the classroom.

There is so much goodness and grace in this book that critiques of it seem almost unfair. The work is stellar in plan and execution, generally improved from the first edition. However, one change, perhaps an editorial mistake, appeared in this Updated Edition: the book repeats the question, “How is the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick celebrated?” both in the main text (#133 and 135, p. 116–118) and in the full list of the questions at the end of the book. In the Updated Edition, there are two different responses to this repeated question. The first edition listed two different questions for each of the responses, one question worded as indicated above, the other given as “What are the emphases in the rite” (p. 90 in the First Edition). It is unclear whether this error is on the part of the author or his editors.

Additionally, while the quotes from saints are a beautiful addition, they are without biographical context; such context might make the quotes more meaningful for readers, especially those becoming more familiar with Catholicism. Likewise, it is very helpful that Pennock includes a section at the end of the book for those “considering becoming a Catholic” (p. 171–172); that section could be enhanced by including more resources, either from the Church’s magisterium or from other classic or contemporary Catholic writers, especially if such a list fell within the parameters of the book’s chapters. Alas, such additions are unlikely, as Pennock died in 2009.

In sum, Michael Pennock’s The Seeker’s Catechism remains a solid introduction to Catholicism, simple in structure, spacious in breadth. It is a fine book to share with those interested in becoming Catholic, with those seeking answers to fundamental questions about our Faith, and with those who need the elements of the Faith explained in terms they can understand. One need not be new to Catholicism to draw riches from its pages, for the truths of our Faith are deep wells worth returning to, no matter where we are on our journey. Under Pennock’s care, the Faith appears as lively, true, good, and beautiful.

Matthew B. Rose (BA, MA, Christendom College) teaches Theology at Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, VA; he writes for a variety of online resources, especially his blog, Quidquid Est, Est.

Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins – Mike Aquilina

Aquilina, Mike. Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins: Twelve Ancient Cities and How They Were Evangelized. Ignatius Press, 2024.

Reviewed by Ted Hirt.

Mike Aquilina is a prolific writer on the Church’s early history. His works include How the Fathers Read the Bible (2022), and The Apostles and Their Times (2017). In Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins, Aquilina provides a fascinating account of a number of the principal cities associated with the rise of Christianity. Many of them will be obvious choices, such as Rome, Jerusalem, and Ephesus. But Aquilina delves deeper and explores the rich history and spiritual legacy of nine other sites. For many readers, the ancient Catholic heritage of these cities will be an intriguing and welcome surprise.

Mike Aquilina is a prolific writer on the Church’s early history. His works include How the Fathers Read the Bible (2022), and The Apostles and Their Times (2017). In Rabbles, Riots, and Ruins, Aquilina provides a fascinating account of a number of the principal cities associated with the rise of Christianity. Many of them will be obvious choices, such as Rome, Jerusalem, and Ephesus. But Aquilina delves deeper and explores the rich history and spiritual legacy of nine other sites. For many readers, the ancient Catholic heritage of these cities will be an intriguing and welcome surprise.

In his Introduction, Aquilina explains several dominating themes. The Roman Empire, like other empires before it, recognized that communities organized themselves into cities, which became centers of commerce, government, religious practices, and considerable unrest, including violent rioting. The Jewish community, out of which Christianity arose, had centered its principal synagogue (the Temple) in Jerusalem, although the Jews principally worshipped in smaller synagogues. The Roman Empire tolerated many religious sects, but Christianity, at times enduring persecution, still flourished in the urban areas. As Aquilina notes, the word “pagan” meant a “country dweller”! He gives us an abbreviated, but fascinating, tour of twelve of these cities. I provide a glimpse of several of them.

We could begin with Antioch, now a small city in the southeastern corner of Turkey, founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals. It was a Greek-speaking city in the middle of a Syrian country, but also had many Jewish residents. Saints Paul and Barnabas preached there; it was in that city that the disciples were first called Christians (Acts 11:26). Unfortunately, the Arian heresy — the belief that Jesus Christ was a created being, not coeternal with the Father — germinated there too. Antioch had a second “brush” with heresy when the apostate Emperor Julian wanted to make the city his capital, but he was killed in Persia before he could accomplish that feat. On a positive note, Antioch was the home of Saint John Chrysostom (b. circa 347 AD). This eloquent theologian initially was a desert ascetic, but he became an orator in the Greek tradition, and his sermons urged Christians to avoid pagan practices and maintain their religious identity.

Carthage in northern Africa (in today’s Tunisia), first an enemy of Rome, later a city begun anew after Roman conquest, emerged as a vibrant center of Christianity. An important city for the export of African grain, it was a center of Latin literary culture, including prominent early Christian writers like Tertullian (b. circa 155 A.D.) and Saint Cyprian (b. circa 200 A.D.). Saint Cyprian ultimately died as a martyr. Last, but not least, is Saint Augustine (b 354 A.D.), whose Confessions are renowned as the first autobiography. In his City of God, Saint Augustine explained that we Christians will suffer in the secular world, but we also belong to the City of God, not to this world. His perspective no doubt was influenced by the siege of Africa by the Vandals.

A final city is Edessa, now Urfa, in southeastern Turkey. Aquilina recounts that its King Abgar is said to have written to Jesus in Jerusalem urging Him to visit his city to heal him of disease. The original account, dated to circa AD 400, asserts that Christ replied and promised to send the king one of his disciples. Aquilina reflects that, even if this narrative is not true, it tells us about the faith of this people, and does corroborate the presence of early Christians there. He notes that the historian Eusebius found evidence of Abgar’s reign. Edessa had Christians who, like faithful believers to the west, suffered persecution from Rome. Among their apologists was Saint Ephrem the Syrian, who apparently incorporated song into his theology, so that the people could comprehend the Incarnation. Unfortunately, like many early Christian cities in the region, it fell under Muslim domination, and apparently few Christians remain there.

My review omits other interesting cities that many do not know as having been important Christian cultural sites: Alexandria, Lugdunum (now Lyon, France), Ejmiastin (in today’s Armenia), Milan, Ravenna, and Constantinople (now Istanbul). Each city is unique, but they all “contributed to the world of Christian ideas,” and arguably each had a “providential purpose.” But Aquilina also contends that, ultimately, these locations do not matter. Why? Because each of the cities contributed to the Roman Catholic faith, but that faith persevered even “if we had removed any one of these cities from the map.” Aquilina concludes that the most important lesson may be that we “treasure our own traditions,” but be flexible too. The Church will endure regardless of the rise or fall of cities.

Aquilina combines scholarship and an easily understandable narrative, no small feat in this field. I highly recommend this book.

Ted Hirt is an adjunct professor at the George Washington University Law School, an assistant editor for the James Wilson Institute’s Anchoring Truths, a former career attorney at the U.S. Justice Department, and a Gettysburg, PA Licensed Town Guide. The views he expresses are his own.

Real Life with Mary – Kelsey Gillespy

Gillespy, Kelsey. Real Life with Mary: Growing in Virtue to Magnify the Lord. Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2024. 181 pages.

Reviewed by S.E. Greydanus.

In her classic Marian work The Reed of God, Caryll Houselander begins by recalling how the advice she received as a child “never to do anything that Our Lady would not do” proved paralyzing rather than edifying “for the very simple reason that I simply could not imagine her doing anything at all.”1 Many people, Houselander continues, share this misconception of Mary “as someone who would never do anything that we do,” and therefore are unable to relate to her as a real, imitable person.2

In her classic Marian work The Reed of God, Caryll Houselander begins by recalling how the advice she received as a child “never to do anything that Our Lady would not do” proved paralyzing rather than edifying “for the very simple reason that I simply could not imagine her doing anything at all.”1 Many people, Houselander continues, share this misconception of Mary “as someone who would never do anything that we do,” and therefore are unable to relate to her as a real, imitable person.2

In Real Life with Mary: Growing in Virtue to Magnify the Lord, Kelsey Gillespy has provided a refreshing antidote to any such image of Mary.

Gillespy begins by recounting her own very personal discovery of Marian devotion, following her entrance into the Church as a young newlywed. This double life change — marriage and conversion — proved the beginning of a challenging transition on many levels, which left her floundering until she turned to Mary. “Up until that point, I’d thought Mary was a passive, goody-two-shoes type, flat and unrelatable,” she explains, all but echoing Caryll Houselander. “But when I started to really look at Scripture — to examine it, gnaw on it, and ponder it as Mary did — I found someone altogether different” (4). The Mary she found, and to whom she introduces readers, is “the greatest heroine to ever live” (8), the maternal model who leads her children through the battle of the Christian life.

The book proceeds through Mary’s life as shown in Scripture, from the Annunciation to the gathering at Pentecost. The chapters each focus on a different virtue as demonstrated by the Blessed Mother and applicable to our own lives. Each opens with a Scriptural passage, followed by an episode from the author’s life and a simple commentary relating that everyday experience to Our Lady. After these, in turn, come “A Soul that Magnifies,” a brief meditation on how Mary demonstrated the virtue in question and what that may look like in readers’ lives; reflection questions, or “Ponder in Your Heart”; an invitation to action, or “Fiat”; and an original prayer.

The lively style of Gillespy’s writing, simple, straightforward, and vibrant, goes a long way toward bringing her subject matter to life. Time and again her reminiscences effectively recreate her experience, whether of milestone days — the glowing excitement of a wedding day, the tension of going into labor without help close by — or little moments that left deep impressions, such as warding off a yellow jacket from one of her children or receiving a “gift” of rocks from another. The same vivid detail then imagines Mary’s experience of comparable milestone days and little moments, with repeated words acting as meaningful refrains.

For example, the first chapter, “Submission to God’s Will,” describes how, at Gillespy’s first pregnancy, a surprise amid difficult circumstances, “my heart skipped and sprinted and hiccuped and faceplanted” (12). At the Annunciation, likewise a surprise presenting a myriad of serious difficulties, Mary’s heart may have done the very same. Then the pattern is established: Mary is relatable in sharing our experience; she is a model for us in how she responds to it.

But, instead of falling to the floor, it seems like Mary steeled herself. She didn’t need to question. For her, there was nothing to sort out. God chose her. God wanted her for this singular role in salvation history.

What more did she need to know?

Submission to God gave her strength. (14)

With nineteen chapters besides the Introduction and Epilogue, each no more than ten pages, the book is an entirely doable length for Gillespy’s fellow busy moms, which is to say for anyone. The titular quest for virtue is especially framed as a quest to discover Mary as a model for women. The questions in the Introduction, those with which the author’s own journey began, run through the entirety: “What does it look like to be a holy woman? A holy wife? A holy mother?” (5)

To be sure, these reflections are not only for wives and mothers — though wives and mothers may especially appreciate the anecdotes drawn from marriage and family life — but for all women. I was reminded of the words so often attributed to St. Edith Stein: “Every woman who wants to fulfill her destiny must look to Mary as the ideal.” Real Life with Mary shows that ideal in both its heavenly splendor and its real-life accessibility.

S.E. Greydanus is a freelance writer/editor, a lay Dominican, and managing editor of Homiletic & Pastoral Review.

Recent Comments