How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization. By R. Jared Staudt. Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose. (skip to review)

John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed. By Ida Friederike Görres. Translated by Jennifer S. Bryson. Reviewed by Clara Sarrocco. (skip to review)

Death in Black and White. By Fr. Michael Brisson, L.C. Reviewed by Betty B. Bosarge, OSF. (skip to review)

Behold Your Mother: Learning to Love Mary with the Saints. By Peter Kahn. Reviewed by Fr. Edward Looney. (skip to review)

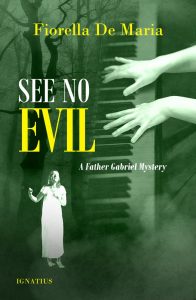

See No Evil. By Fiorella De Maria. Reviewed by Lawrence Montz. (skip to review)

How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization – R. Jared Staudt

Staudt, R. Jared. How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization. Gastonia, NC: TAN Books, 2023. 345 pages.

Reviewed by Matthew B. Rose.

Sometimes, emergencies reawaken in us our former fervor, lost in complacency, for what should have been most important. For the Church in the United States, such an emergency was a 2019 Pew survey which reported that only approximately one third of American Catholics believed that the Eucharist is actually Jesus’ Body and Blood, while close to 70% held that the Eucharist is just a symbol. From this pastoral and catechetical emergency came the Eucharistic Revival, which has reawakened American Catholics’ devotion to the Eucharist. Tied with this Revival, and its culminating National Eucharistic Congress in 2024, are a myriad of media, both in print and digital, to help Catholics sink deeper into this great Mysterium Fidei, this Mystery of the Faith. R. Jared Staudt’s How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization, one such work, seeks to do more than merely fan devotional flames. Staudt seeks to set the Eucharist at the center not only of our private devotion, but as the center of a societal transformation.

Sometimes, emergencies reawaken in us our former fervor, lost in complacency, for what should have been most important. For the Church in the United States, such an emergency was a 2019 Pew survey which reported that only approximately one third of American Catholics believed that the Eucharist is actually Jesus’ Body and Blood, while close to 70% held that the Eucharist is just a symbol. From this pastoral and catechetical emergency came the Eucharistic Revival, which has reawakened American Catholics’ devotion to the Eucharist. Tied with this Revival, and its culminating National Eucharistic Congress in 2024, are a myriad of media, both in print and digital, to help Catholics sink deeper into this great Mysterium Fidei, this Mystery of the Faith. R. Jared Staudt’s How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization, one such work, seeks to do more than merely fan devotional flames. Staudt seeks to set the Eucharist at the center not only of our private devotion, but as the center of a societal transformation.

To non-Catholic Christians, so much ado might seem strange. Why, our separated brethren might ask, are Catholics so concerned about Eucharistic devotion, when other societal issues pose more widespread concern? Staudt, while addressing this objection in so many words, does provide an answer. The Eucharist, to use the language of Lumen Gentium, is the “source and summit of the Christian life.” Thus, Staudt structures his book showing that true devotion to the Eucharist affects other areas of Christian life, even those beyond the merely spiritual.

Staudt begins his reflections at the “Source” of our Eucharistic devotion: not the Last Supper, nor Israel’s sacrificial system, but our human need to eat and, in eating together, build our relationships with each other. Then, tracing the relationship between eating and the right worship of God, Staudt surveys the development (in a doctrinal sense) of the Eucharist through Salvation History. This scriptural and theological history culminates in the Incarnation, when God enters into history and feeds His people, first in signs and miracles, then perfectly in giving Himself at the Last Supper and the Cross. From this pivotal moment flows the Church, through which our Eucharistic Lord enacts His salvific plan within this world (Staudt uses the term “Eucharistic Church” to highlight this ecclesiastical mission).

In Part II, Staudt discusses the Eucharist as the “Summit” of the Christian life, and in the process shows how Eucharistic devotion vivifies all aspects of the sacraments. Herein lie beautiful discussions of how the Mass and Eucharistic Adoration can “be amazingly transformational” in our relationship with God and with others, as well as within our private lives. Staudt emphasizes how approaching the Eucharist as the “Summit” requires preparing to receive the Eucharist, most especially through sacramental confession, and in actively participating in Eucharistic celebrations.

Part III provides ways in which Eucharistic devotion can transform our lives as Christians, providing a source of cultural restoration. The transformation reaches every area of our lives, from Sundays, feast days, and liturgical seasons; to the construction of our churches, whereby architecture draws us into eternity; to how we take the Eucharist into the world through processions, on the one hand, and in our service to the most vulnerable in our society, on the other. In this way, our culture becomes a true culture, that is, one drawing its life from a cultus, from our worship. As Staudt says, “The Eucharist provides the nourishment Christians need for their work in the world, feeding them with the sustaining power of God’s divine life” (272–273).

One key aspect of any culture is its artwork. To emphasize this aspect of a Eucharistic culture, Staudt peppers his book with discussions of works of art from the western heritage, mostly, though not exclusively, works focused on Eucharistic devotion. Art acts as a teacher, instructing through aesthetics what argumentation might miss. Indeed, this aspect of the book, in this reviewer’s opinion, is its most fantastic and most frustrating feature. On one hand, the artistic selections greatly enhance the theological reflections, concretizing Staudt’s verbal catechesis, drawing the reader into a culture wherein the Eucharist is, indeed, the source of life. Beauty, as always, attracts. On the other hand, Staudt can only provide brief excursuses about any given piece. While this ensures Staudt addresses each work, it means in practice that most pieces receive only a passing comment. Indeed, a fuller treatment of these artistic works, discussing their place in history and in a Eucharistic civilization, would require another book-length treatment itself. One hopes, among his other projects, that Staudt might consider such a sequel.

Pastors, catechists, and directors of Faith Formation will find much in How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization for faith formation, homilies, and parish group discussions. Ministries could discuss the works of art presented in the book, using Staudt’s comments as points of discussion. One appendix lists “Recommended Books” for further study; an enterprising parish might add short blurbs about these works in their bulletin or parish magazine. Likewise, a second appendix includes various prayers for Eucharistic devotion both internal to and external to the Liturgy.

Key moments in Church history have left lasting legacies, legacies both planned by Church authorities and those unexpected, yet delightfully embraced by the laity. The call to cultural transformation presented by How the Eucharist Can Save Civilization represents the latter, a response to this kairos in the history of the Catholic Church in the United States. One cannot but hold out hope, indeed, hold onto theological Hope, that we will return to our cultural center, Christ our Eucharistic Lord, and thus preserve our civilization.

Matthew B. Rose (BA, MA, Christendom College) teaches Theology at Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, VA; he writes for a variety of online resources, especially his blog, Quidquid Est, Est.

John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed – Ida Friederike Görres

Görres, Ida Friederike. John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed. Translated by Jennifer S. Bryson. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. 2024. 291 pages.

Reviewed by Clara Sarrocco.

John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed is actually two books intertwined into one. It presents an insight into the soul and thoughts of Ida Frederike Görres, the author and into the soul and thoughts of John Henry Newman, the main subject.

John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed is actually two books intertwined into one. It presents an insight into the soul and thoughts of Ida Frederike Görres, the author and into the soul and thoughts of John Henry Newman, the main subject.

Jennifer S. Bryson explains: “Another aspect of the significance of this book — and part of my motivation to translate it — is that it is also a about Ida Friederike Görres.” (7) Bryson continues to explain the difficulties she encountered: “What I had before me was a text in German not only containing what Görres herself wrote about Newman but also full of quotations from Newman. . . largely with no citations.” (9) She explains that with much hard work and detective work she was able to resolve most of the difficulties. Bryson dedicates her translation to Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz who has attempted to keep the memory of Ida Görres alive.

In 1998 a German manuscript of this book was found in the possession of members of Görres’s family. Most of the manuscript was handwritten and in draft mode. It appears as if Görres had planned to publish her book around 1944–1945. These years coincide with her great productivity with writing, lecturing, and working with youth groups. The book on Newman remained only partially formed. Her love and admiration of Newman is unquestioned; Görres wrote: “If you ask me what really moves and captivates me most about the great figure of our ‘Father Newman,’ as we call him with love and adoration . . . it is the one realization that Newman was a man who was sacrificed.” (Gerl-Falkovitz, 35) By 1950, after her research and writing, she determined that her book would be about Newman the Saint.

In the opening chapter, “Initial Reconnaissance,” Görres explains the difficulty of writing a biography of someone one has never met, most particularly since her aim is to capture Newman’s inner spirit and not just the facts of his life. “In the following [chapters] we want to try to investigate the person of Newman: . . . the saint of the church and the saint of humility, the one perfected in sacrifice.” (59)

In “Chapter 2 – The Golden Apple,” Görres discusses the milieu that Newman was born into. On page 61 she writes: “One of the main motifs of the nineteenth century, so rich in questions, new beginnings, and experiments, is the act of reaching for the Golden Apple.” In “Chapter 3 – Newman’s Religious and Human Character in Letters and Sketches,” she highlights parts of Newman’s life that other biographers tend to overlook. For instance, Görres quotes from a letter from Newman’s mother where she writes: “Your fault is a want of self-confidence and a dissatisfaction with yourself.” (79) Newman responds by agreeing, stating that these observations are “neither new nor slightly founded.” Despite this, “Because he genuinely renounced all human ties for the sake of the kingdom of heaven, he received a hundred times over already in this life. Few people have been loved like him.” (90)

Newman’s dedication to the Truth Görres explains in “Chapter 4 – Passion for the Truth.” She writes: “The drama of his fate, which is so quiet on the outside, tragically tense and moving on the inside is played for the sake of the Truth . . . Newman is one of those people . . . a rarity, from whom Truth is the central concern of life. . . .” (93) In Newman’s time the English church had become a state church. Newman and his friends began the Tractarian movement to try to resolve this problem. Newman believed in the Via Media between the English and Roman church. He received much vitriol over his writings and sermons, as Görres describes in “Chapter 5 – Taking Christianity Seriously: The Tracts and Sermons.”

In “Chapter 6 – Rome,” Görres captures the great anguish and torment of soul Newman experienced before his turn to the Roman Catholic Church. He had very little contact with Catholics and was not enamored with some Catholic beliefs and practices, yet he felt drawn by heart more than logic. He spent years at Littlemore praying and fasting to find the way, knowing that his conversion would separate him from friends, family, and colleagues.

“Chapter 7 – Newman Brought Low” is the most poignant and touching of all the chapters. It recounts Newman’s rejection by his Anglican friends and colleagues for entering the Church of Rome, but more disturbing is the treatment he received from his fellow Catholic clerics, some of whom were converts themselves. “And he never gets a chance. Every attempt, every approach fails: the university in Ireland, the great Catholic magazine [Rambler], the Bible translation, the student chaplaincy at Oxford. These are carefully and cruelly destroyed by his confrères, by the bishops . . . .” (170) “But his answer to everything is great trust in the Lord of the Church. . . .” (184) Chapter 7 is Görres’s best.

The remaining four chapters discuss Newman’s piety, two poems by Newman, an essay by Görres on conscience, and Newman’s ideas on conscience taken mostly from his sermons. In the “Encore” section there is a sketch and a timeline of Newman’s life, a timeline of the life of Ida Friederike Görres, a “Register of Persons” noted in the book, an extensive bibliography and an Index.

John Henry Newman: A Life Sacrificed is a different sort of biography. It attempts to delve into the heart and soul of Newman, and successfully so. Because it is a translation from the German, certain passages seem strange to the English-speaking ear i.e. the overuse of rhetorical questions and the effusive use of adjectives. Still an interesting read.

Clara Sarrocco is the longtime secretary of The New York C.S. Lewis Society. Her doctoral dissertation was on C.S. Lewis and von Hildebrand.

Death in Black and White – Fr. Michael Brisson, L.C.

Brisson, L.C., Fr. Michael. Death in Black and White: A Novel. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2024. 366 pages.

Reviewed by Betty B. Bosarge, OSF.

Do you like to relax with a good mystery novel, the kind that will keep you awake half the night? Over the years there have been novels featuring priest detectives like G.K. Chesterton’s Fr. Brown, William Kienzle’s Fr. Robert Koesler, and Margaret Coel’s Fr. John O’Malley. But there hasn’t been one quite like the priest in Death in Black & White, based on real life in Westchester County, NY, and the imagination of Legionary of Christ priest Fr. Michael Brisson.

Do you like to relax with a good mystery novel, the kind that will keep you awake half the night? Over the years there have been novels featuring priest detectives like G.K. Chesterton’s Fr. Brown, William Kienzle’s Fr. Robert Koesler, and Margaret Coel’s Fr. John O’Malley. But there hasn’t been one quite like the priest in Death in Black & White, based on real life in Westchester County, NY, and the imagination of Legionary of Christ priest Fr. Michael Brisson.

It is a novel that goes inside the rectory and the personalities who dwell there, from the retired pastor, Msgr. John Leahy, who won’t leave even when the new pastor moves in, to the machinations of parish staff members, and the problems young Fr. Christopher Hart faces in his first assignment as pastor of St. Dominic’s Church, a parish that has not been doing too well.

With an engaging sense of humor, Fr. Brisson develops the characters in a way that we can recognize them in people we know. The pastor emeritus, Msgr. O’Malley, he describes as the parish’s very own Archie Bunker. Housekeeper Maria is “a saint who started her day at Mass and ended it on her knees in the Marian chapel.” Then there is Fr. Christopher’s best friend from the seminary, Fr. Andrew Reese, who is working on a doctorate in Rome.

Fr. Christopher realized he needed help waking up the parishioners, who barely participated in parish events. So he developed some big plans. To bring his plans to fruition, he lured Fr. Andrew, a gifted preacher, back from Rome to be his associate.

Daily parish life goes into a tailspin when Fr. Christopher discovers he must deal with the Mafia operating in his parish. Msgr. O’Malley had been responding to calls from the local Mafia don to hear the confessions of people about to die a “white death.” These were Catholics slated to be murdered for whatever offenses they committed against the Mafia. The Mafia boss was a “devout Catholic” who wanted to make sure his victims had an opportunity to go to Heaven with a last confession. The “black death” was reserved for those Mafioso who would simply become mob hits and were not deemed to be worthy of the Sacrament of Reconciliation.

I asked Fr. Brisson how he learned about the “white death” and “black death,” and he said these rituals, which evolved in Sicily, were explained to him by a priest in New York who received a call one night with a request for last rites.

“He asked for an address, but was told he’d be picked up,” Fr. Brisson said. “A bit later a car showed up at the rectory, and he was brought to a farmhouse outside the city (not New York). The whole set-up said Mafia. They brought him to a room upstairs, where he found a young guy, late teens, early twenties, twitching with nervousness. It turned out he had been in the wrong place at the wrong time, and they needed to take him out. But, since it was just business and nothing personal, they allowed him to go to confession first. The priest received an unmarked envelope in his mailbox the next morning with an honorarium for services rendered.”

Fr. Brisson talked to other priests who had direct contact with the Mafia. What he learned helped him write a very realistic fictional book. His characters are a blend of people he knew over the years, both in New York and in Rome, where he currently serves as councilor to the superior general of the Legionaries of Christ and heads their Department for Priestly Life.

Fr. Brisson has a way with humor, subtle in some cases and in others generating a good laugh. But there are some serious contemporary issues he describes well. What happens when a priest is falsely accused of molesting a minor? His description of how the priest is treated by Chancery officials is sickening, hard to read without getting angry at the bureaucrats in collars who dismiss their brother priests as if they no longer exist.

Fr. Brisson described the three main priests in the novel as representing archetypes of sorts. Fr. Christopher is “the young, enthusiastic, somewhat naïve priest with a heart of gold. Fr. Andrew is a type of priest I’ve met too often but thankfully has become a less and less frequent character among clergy: the bon vivant, who’s all about appearances, who wants to climb the ecclesiastical ladder, who loves his fine wine, fettucine carbonara, and being called Father, but the salvation of souls is far from his mind. Msgr. Leahy is the old curmudgeon who’s been around the block one too many times and represents a counterpoint to Fr. Christopher’s young, enthusiastic, anything-is-possible spirit, whereas Fr. Andrew is the counterpoint to Fr. Christopher’s purity of mission.”

These are priests we’ve all met over the years. Death in Black & White is one of the best mystery novels of the year. It may cause you to rush through homily preparation to get to the next exciting chapter as the action intensifies to the gripping ending. The good news is: Fr. Brisson is writing his second book.

Dr. Betty Bosarge, OSF is a retired criminologist who specialized in Traditional Organized Crime and police training. She serves as spiritual formation minister for Secular Franciscans in Austin, TX.

Behold Your Mother – Peter Kahn

Kahn, Peter. Behold Your Mother: Learning to Love Mary with the Saints. London: Catholic Truth Society, 2023. 96 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Edward Looney.

In his concise 96-page book, Behold Your Mother: Learning to Love Mary with the Saints, Peter Kahn shares his devotion to Mary and explores her role through the lens of the saints. The Christian is invited to “behold” Mary — Jesus’ own words spoken from the cross. The reader will behold Mary specifically through the lives, writings, and witness of the saints. Several saints enjoy recurring references throughout the short treatise, such as St. John Paul II, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Maximilian Kolbe, St. Teresa of Calcutta, and others, showcasing Kahn’s favorite saints while also introducing lesser-known figures, such as the Russian Orthodox mystic Seraphim of Sarov.

In his concise 96-page book, Behold Your Mother: Learning to Love Mary with the Saints, Peter Kahn shares his devotion to Mary and explores her role through the lens of the saints. The Christian is invited to “behold” Mary — Jesus’ own words spoken from the cross. The reader will behold Mary specifically through the lives, writings, and witness of the saints. Several saints enjoy recurring references throughout the short treatise, such as St. John Paul II, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Maximilian Kolbe, St. Teresa of Calcutta, and others, showcasing Kahn’s favorite saints while also introducing lesser-known figures, such as the Russian Orthodox mystic Seraphim of Sarov.

As one reads Behold Your Mother, they will discover practical tips for Marian devotion. Kahn encourages the reader to find a special shrine/chapel to Mary or a statue or devotional area near them, so the person can schedule time there to pray or celebrate a Marian feast day. Other recommended devotions include the Rosary, the miraculous medal, a single Hail Mary, carrying a statue of Our Lady with you, or spending time with Our Lady each day in a personal conversation.

An interesting parallel Kahn makes is to put Marian devotion alongside different spiritual traditions. He does this with the daily examen and with St. Teresa of Avila’s mansions of the interior castle. Kahn asserts that the examen of one’s day aligns with Mary’s pondering of the events of her life. In the case of the examen, a person ponders over the graces received and those with which they failed to cooperate. Kahn also draws connections between the mansion of St. Teresa of Avila and Marian devotion. For example, the third mansion treats dryness in prayer, which the author likens to persevering in praying the Rosary. In the fourth mansion it is the awareness that one draws everything from God. He provides the example of St. Thérèse, who once said, “And I cannot pray. I can only look at Our Blessed Lady and say: Jesus” (p. 72). The fifth mansion pertains to union with God, which parallels with Mary’s role as a mother in our spiritual maturity. The sixth mansion addresses trials, in which a person can turn to Our Lady for her maternal assistance. The final mansion is attained through conversion of one’s life, which leads Kahn to reflect on Mary as conceived without sin. When it comes to the parallels of the examen and the mansions, the analogy might be forced, but he offers a new and different perspective for the reader to consider.

One shortcoming of the book is the rushed pace with which some topics are introduced. Given the brevity of the book, it is hard to explain complex terms and theology. However, by introducing the theological topic and simple explanation, Kahn invites the reader to further study through referenced resources. For example, he introduces subjective redemption by quoting and pointing to Fr. Aidan Nichols’s book There Is No Rose. Kahn must assume that the reader would understand subjective redemption, or by drawing attention to Nichols’s Mariological text, hopes that the reader will continue their study of Mary by acquiring that title (c.f. p. 79).

Another questionable statement I found in the text states, “The earliest account of an apparition of Mary comes from Gregory of Nyssa in 380” (p. 20). I will not dispute this claim outrightly, but I will qualify it with the tradition of Mary’s bilocation to St. James in Zaragoza. If one wishes to differentiate the bilocation from an apparition, then Kahn’s assertion is true; if one accepts the common parlance of Zaragoza, it also was an apparition. If by earliest account, he means documented apparition, rather than an oral legend later written down, then he may also be correct as I do not know the exact emergence of the Zaragoza apparition in written form.

Kahn’s short treatise on Our Lady, Marian devotion, and the witness of the saints will prove beneficial to anyone who wishes to learn more about Our Lady and be uplifted by the example and wisdom of the saints. It is not a dense Mariological work, which makes it accessible. It serves as an excellent primer, reinforcing one’s knowledge or reminding them of things they may have forgotten or take for granted. With the saints, Peter Kahn helps us fulfill Jesus’ command to behold His mother.

Rev. Edward Looney was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Green Bay in 2015 and is a Marian theologian. He received an STL from the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein in 2023. A former president of the Mariological Society of America and the Society’s current Secretary, he is the author of several Marian titles and hosts a weekly interview-based podcast.

See No Evil – Fiorella De Maria

De Maria, Fiorella. See No Evil: A Father Gabriel Mystery. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2020. 299 pages.

Reviewed by Lawrence Montz.

See No Evil: A Father Gabriel Mystery clearly falls into the category of a twentieth-century English detective novel in the grand tradition of P.D. James. The story exhibits detailed characterizations surrounding the mystery at hand, a progression of pertinent clues fed over the pages of the novel, often presented with misdirection but not deception. The countryside of post-World War II England presents the tapestry upon which the mystery is developed. The protagonist is a Catholic clergyman, but here the novelistic tool departs from a Brother Cadfael or Father Brown-type character to a very real servant of God who portrays his Church and faith as normal elements of life, not as some cartoon caricature of a priest.

See No Evil: A Father Gabriel Mystery clearly falls into the category of a twentieth-century English detective novel in the grand tradition of P.D. James. The story exhibits detailed characterizations surrounding the mystery at hand, a progression of pertinent clues fed over the pages of the novel, often presented with misdirection but not deception. The countryside of post-World War II England presents the tapestry upon which the mystery is developed. The protagonist is a Catholic clergyman, but here the novelistic tool departs from a Brother Cadfael or Father Brown-type character to a very real servant of God who portrays his Church and faith as normal elements of life, not as some cartoon caricature of a priest.

Father Gabriel is a faithful minister of the Lord but certainly not a saint or moralistic icon. His presence in the story helps develop moral implications about life without becoming overtly high-minded. The narrative displays a small cast of both sympathetic and unsympathetic suspects and the reader is challenged to form conclusions based upon clues dispersed throughout the novel rather than judgements based upon behavior alone. It is clear from the beginning that the victim is not thought well of by the other characters, so of course all seemingly have valid motives for the crime.

The author, as in many other English crime tales, is female. Fiorella De Maria, while being of Maltese extraction, actually grew up in the Wiltshire countryside that serves as the setting of the mystery. See No Evil is the third offering in the detective series featuring Father Gabriel, a widowed Benedictine monk. De Maria is a graduate of Cambridge. She has written several fiction and nonfiction books and has appeared on both BBC and EWTN. Besides her writing career, she is a noted bioethicist and extends some of these behavioral concepts into “real” life situations.

Fans of crime stories may form the core reader group of this whodunit novel, but this story offers all readers insights into life as well as the criminal tale. Too many books of this kind fall short in characterization and plot development. Those are not issues with De Maria’s writings. Without divulging too much of the plot or accidentally steering the reader to a premature conclusion, a short synopsis should help peek the crime venue reader’s interest in See No Evil. The deceased character is shown to be one that had been very hard upon and often judgmental of both his family and society as a whole. His wartime service as a field journalist exposed him to some of the most tragic occurrences in life but his unpleasant nature was developed long before experiencing the traumatic events of war first hand. His hardness of heart in part caused his wife to require internment in an asylum at an early age, which made his harmful impacts on his son and daughter that much more poignant. His brother detested him and he did not seem to have any true friends. One wonders why the victim was even invited to the home of his daughter’s benefactors.

In fact, it was likely that the animosity of the hosts to the victim was the reason Fr. Gabriel was even invited to their estate, that is, the hope that the caring priest might serve as a buffer to the unpleasantness of the man. There was no shortage of potential perpetrators. It becomes obvious that the cast of characters feel the same way about each other’s motives to remove the deceased from the scene and these concerns lead to misguided attempts to protect those whom they suspected of the death. Of course all of this clearly muddies the water for the armature sleuth, Farther Gabriel, and the confused police inspector of Wiltshire.

The novel presents not only a vivid portrait of post-war England and a classic murder mystery but a lesson in proper Christian ethics in the final scenes. How the reader would respond in a similar situation poses an interesting dilemma. See No Evil challenges us to question our potential response.

Lawrence Montz is a Benedictine Oblate of St. Gregory Abbey in Shawnee, Oklahoma, past Serran District Governor of Dallas, and serves as his Knights of Columbus council’s Vocations Program Director. He resides in the Dallas Diocese.

Speak Your Mind