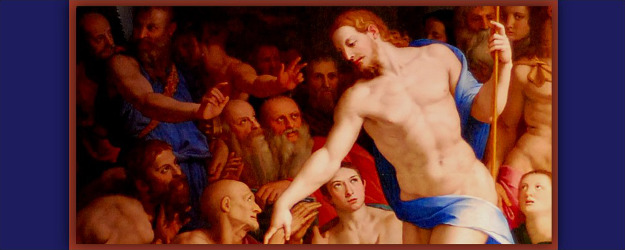

Detail of the fresco Descent of Christ into Limbo, by Agnolo Bronzino (1552).

Introduction

The encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, has a specific place in the ministry of Pope St. John Paul II. It was proclaimed the first Sunday of Lent, 1979, the first encyclical of the new pontificate, hence the link to Advent—it marked an Advent event to a pontificate and takes this theme in setting out a way forward for the pope’s ministry.

We have the advantage of looking back on the events of John Paul II’s life and knowing what was to come. In fact, we are so familiar with what happened, that we know what events brought him to his redemption, as confirmed by his canonization. He has gone through his creation, fall, incarnation, passion, death, and resurrection, and we look forward to sharing in the parousia. Now, John Paul II shares with the Father the eternal banquet. But we witnessed the spiritual life of this saint-in-the-making, as we worked, played, studied, and grew spiritually ourselves.

What was it that John Paul II mapped out in reflecting on the redeemer of man? What was the style he used which became a blueprint for his ministry? John Paul II’s writings were profoundly theological. He produced three encyclicals—Redemptor Hominis, the Redeemer of Man, based on Christ as redeemer; Dives in Misericordia, on God the Father; and Dominum et Vivificantem, on the Holy Spirit. Christ, the Redeemer of Man, true man and God, centers on the Incarnation and its connection to the Redemption of the whole of creation. It came as the result of an Advent event—the Annunciation. The term, Redemptor Hominis, refers to an Advent, a prophetic reflection on what is to come, and how it will affect salvation history.

The encyclical, written only 14 years after the close of Vatican II, follows the example of a similar document written by Pope Paul VI at the beginning of his pontificate. Redemptor Hominis includes many references to Vatican documents and scripture. Most important, it reflects on, exposes, and gives prophetic voice to, the path of the Church, and above all, redemption for all. Specfically, it states that the answer to sin is the promise of our redemption. This cannot be done by human power, only by the God of love. The Incarnation, the Advent of the Son of God, opens the door to the redemption of all creation, and it is from this perspective that I have chosen this encyclical as an Advent reflection for our time.

John Paul II explores four themes in Redemptor Hominis:

- Inheritance

- The Mystery of the Redemption

- Redeemed Man and His Situation in the Modern World

- The Church’s Mission and Man’s Destiny

Inheritance

Rather than looking at what has gone before—our inheritance, Redemptor Hominis is framed in the future, but with reference to a priceless gift received from our past. Our inheritance is our redemption. According to John Paul II, it is within our grasp now, we inherit it now, but we also need it for the future. The pope’s opening thoughts concerned the end of the millennium. It was looming on the horizon, yet he seemed aware that it was within his grasp in his own lifetime.

We also are in a certain way in a season of a new Advent, a season of expectation: “In many and various ways God spoke of old to our fathers by the prophets; but in these last days, he has spoken to us by a Son …,” by the Son, his Word, who became man and was born of the Virgin Mary. This act of redemption marked the high point of the history of man within God’s loving plan. God entered the history of humanity and, as a man, became an actor in that history, one of the thousands of millions of human beings, but, at the same time, Unique! (RH 1)

John Paul II recalls the papal election and the choosing of his new name. Drawing on the words of the documents of Vatican II and Pope John XXIII, he calls for the guidance of the Spirit of Trust and Love. Attempting to interpret the significance of Vatican II, he refers to Pope Paul VI’s first encyclical and to two issues critical for the future of the Church:

First, Collegiality and the Apostolate. John Paul II saw these as building blocks for the stability and future for the Church.

The Council did more than mention the principle of collegiality: it gave it immense new life, by—among other things—expressing the wish for a permanent organ of collegiality, which Paul VI founded by setting up the Synod of the Bishops, whose activity not only gave a new dimension to his pontificate, but was also, later, clearly reflected in the pontificate of John Paul I, and that of his unworthy Successor from the day they began. (RH 5)

The Synod continues to this day, recently implemented by Pope Francis for the purpose of consulting the whole Church on family life. The managerial structure of the Church is under constant renewal, but the basic elements of collegiality and apostolic succession remain.

Second, Christian Unity. John Paul II sees Christian disunity as going to the heart of the Church, and must be addressed because it affects the whole of society. If only the Church could be one, it would be a shining example for the rest of humanity, and the human family would become one as well.

It is a noble thing to have a predisposition for understanding every person, analyzing every system and recognizing what is right; this does not at all mean losing certitude about one’s own faith or weakening the principles of morality, the lack of which, will soon make itself felt in the life of whole societies, with deplorable consequences besides. (RH 6)

In this document, we see the seeds of some of John Paul II’s later teachings, including his Apostolic Letter, Novo Millennio Inuente, on the Church’s priorities for the third millennium, and his epic encyclical, Veritatis Splendor, in which he defines the Church’s role in moral teaching. Both Familiaris Consortio and Evangelium Vitae further discuss the breakdown of the human family, and the devaluing of human life. In Redemptor Hominis 6, as in these later writings, John Paul II states that the fracturing of society will lead to moral decline. As he predicted, the Culture of Death, as defined by abortion on demand, embryonic stem cell research, in vitro fertilization, and euthanasia have all become destructive realities for today’s human family.

The Mystery of the Redemption

Redemption is Christocentric.

What should we do, in order that this new advent of the Church connected with the approaching end of the second millennium may bring us closer to him whom Sacred Scripture calls “Everlasting Father,” Pater futuri saeculi? This is the fundamental question that the new Pope must put to himself on accepting in a spirit of obedience in faith the call corresponding to the command that Christ gave Peter several times: “Feed my lambs,” meaning: Be the shepherd of my sheepfold, and again: “And when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.” (RH 7)

John Paul II reflects on the role of the Good Shepherd in this passage, then goes further in describing the relationship of Christ with his Church.

“For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified.” The Church stays within the sphere of the mystery of the Redemption, which has become the fundamental principle of her life and mission. (RH 7)

By being redeemed, mankind is made anew, all of the past is wiped away, and a new future is given. Because Christ is the second Adam, the New Man, the Incarnation goes to the very heart of God’s greatest creation which was seen as “very good.”

In its penetrating analysis of “the modern world,” the Second Vatican Council reached that most important point of the visible world that is man, by penetrating like Christ the depth of human consciousness and by making contact with the inward mystery of man, which in biblical and non-biblical language is expressed by the word “heart.” Christ, the Redeemer of the world, is the one who penetrated in a unique, unrepeatable way into the mystery of man and entered his “heart.” (RH 8)

By doing so, Christ creates a love story—of heart speaking to heart. God, as Son and Man, speaks to man’s heart, as only a heart can speak.

So much so, that “God is Love” (RH 9).

This is not just about God revealing himself to man; there are two sides to this relationship.

Man cannot live without love. He remains a being that is incomprehensible to himself, his life is senseless, if love is not revealed to him, if he does not encounter love, if he does not experience it and make it his own, if he does not participate intimately in it. This, as has already been said, is why Christ the Redeemer “fully reveals man to himself.” (RH 10)

John Paul II always referred to the nature of the person when considering ethical issues—only by discovering who we are, do we discover our moral dignity, our Imagio Dei—we are created in the image and likeness of God. John Paul II was consistent, honest, reasoned, and logical in the concept of who we are—and, above all, how this feeds into how we discover God.

The Church has a mission which is based on Christ; John Paul II extends this mission explicitly to non-Catholics also, following his theme on ecumenism.

Jesus Christ is the stable principle and fixed center of the mission that God himself has entrusted to man. We must all share in this mission and concentrate all our forces on it, since it is more necessary than ever for modern mankind. (RH 11)

John Paul II was aware of the disunity in the world and reflects on this in relation to the teachings of Gaudium et Spes—the pastoral constitution of Paul VI on the Church in the modern world.

The Church respects human freedom, but there is a unity which exists by the mere fact we are all human. We need to consider what we have in common—our humanity—rather than merely what divides us.

We perceive intimately that the truth revealed to us by God imposes on us an obligation. We have, in particular, a great sense of responsibility for this truth. By Christ’s institution, the Church is its guardian and teacher, having been endowed with a unique assistance of the Holy Spirit in order to guard and teach it in its most exact integrity. In fulfilling this mission, we look towards Christ himself, the first evangelizer. (RH 12)

The teaching on the New Evangelization, started by Paul VI, was expressed more fully by John Paul II in Novo Millennio Inuente.

Redeemed Man and His Situation in the Modern World

What is the situation of redeemed man in the modern world? John Paul II proclaims that redeemed man is the very center of God’s creation because the Incarnation unites God with man through Christ. Man is not a political tool, something to be played with, but is the Masterpiece of God’s Creation. Thus, all human activity should focus on the dignity of man.

“Man is the only creature on earth that God willed for itself.” Man as “willed” by God, as “chosen” by him from eternity and called, destined for grace and glory—this is “each” man, “the most concrete” man, “the most real”; this is man in all the fullness of the mystery in which he has become a sharer in Jesus Christ, the mystery in which each one of the four thousand million human beings living on our planet has become a sharer from the moment he is conceived beneath the heart of his mother. (RH 13)

Note that John Paul II defines one to be a human being from the moment “he is conceived.”

For the Church to follow the right path, as the Body of Christ, it must fully understand and appreciate the value of the human person. At no time may it consider anything of greater value because human persons constitute the Body of Christ. Thus, the Church in the modern world must be aware of, and address, all that threatens the human person.

God gave man the task of overseeing the visible world—but by what values are we guided? God’s visible creation is so vast! But our values must be spiritual.

The essential meaning of this “kingship” and “dominion” of man over the visible world, which the Creator himself gave man for his task, consists in the priority of ethics over technology, in the primacy of the person over things, and in the superiority of spirit over matter. (RH 16)

As technology progresses, man states that “he can do it,” but he should be asking, in the name of God, “should he be doing it?” God gave us certain rights, but also the responsibility to ensure those rights.

While sharing the joy of all people of good will, of all people who truly love justice and peace, at this conquest, the Church, aware that the “letter” on its own can kill, while only “the spirit gives life,” must continually ask, together with these people of good will, whether the Declaration of Human Rights and the acceptance of their “letter” mean everywhere also the actualization of their “spirit.” (RH 17)

John Paul II sought to defend human rights throughout his papacy—in the womb, in the hospice, and on the battlefield. He understood the dire effects of international conflict on human society and lived to see some of the fruits of his labor: in the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and in its relatively calm restructuring into a democratic society.

The Church’s Mission and Man’s Destiny

The Church is concerned with the universal call to holiness and how this leads man to his destiny—redemption. It is the Church’s responsibility to teach the Truth, and at no time may it stray from this mission. Nor is there any earthly power to do so.

“The word which you hear is not mine but the Father’s, who sent me.” Nobody, therefore, can make of theology, as it were, a simple collection of his own personal ideas, but everybody must be aware of being in close union with the mission of teaching truth for which the Church is responsible. (RH 19)

John Paul II does not just speak of the splendor of Truth, but in union with the Church, he also reminds us of the tools available on order to put our spirituality into action. The sacraments of Eucharist and penance especially provide us with God’s grace to send us to new levels of faith and mission.

Nevertheless, it is certain that the Church of the new Advent, the Church that is continually preparing for the new coming of the Lord, must be the Church of the Eucharist and of Penance. Only when viewed in this spiritual aspect of her life and activity is she seen to be the Church of the divine mission, the Church in statu missionis, as the Second Vatican Council has shown her to be. (RH 20)

Our vocation is meant to mirror the three offices of Christ, as priest, prophet, and king. These offices enable us to serve our fellow man on his path to redemption.

John Paul II ends Redemptor Hominis by making a direct reference to Mary, our Mother, and Mother of the Redeemer. Her call in Advent, at an Advent time of her life, led to an Advent in the redemption of mankind, which, through the Resurrection, is a constant and renewing Advent for all time. This link, which Mary gives us to the Redeemer of Man, is unique.

We believe that nobody else can bring us, as Mary can, into the divine and human dimension of this mystery. Nobody has been brought into it by God himself, as Mary has. It is in this, that the exceptional character of the grace of the divine Motherhood consists. Not only is the dignity of this Motherhood unique and unrepeatable in the history of the human race, but Mary’s participation, due to this Maternity, in God’s plan for man’s salvation through the mystery of the Redemption is also unique in profundity and range of action. (RH 22)

May Advent be a profoundly spiritual experience as we prepare for the birth of our Savior, who promised redemption to all mankind—without exception. It is up to us to respond humbly and faithfully to the implications of the Incarnation. May divine grace help us in this call to holiness.

Recent Comments